The path to resilience: MSC’s ecosystem approach to adaptive social protection (ASP)

by Aarjan Dixit, Akshit Saini, Mahima Dixit and Ritesh Rautela

by Aarjan Dixit, Akshit Saini, Mahima Dixit and Ritesh Rautela Jun 24, 2025

Jun 24, 2025 6 min

6 min

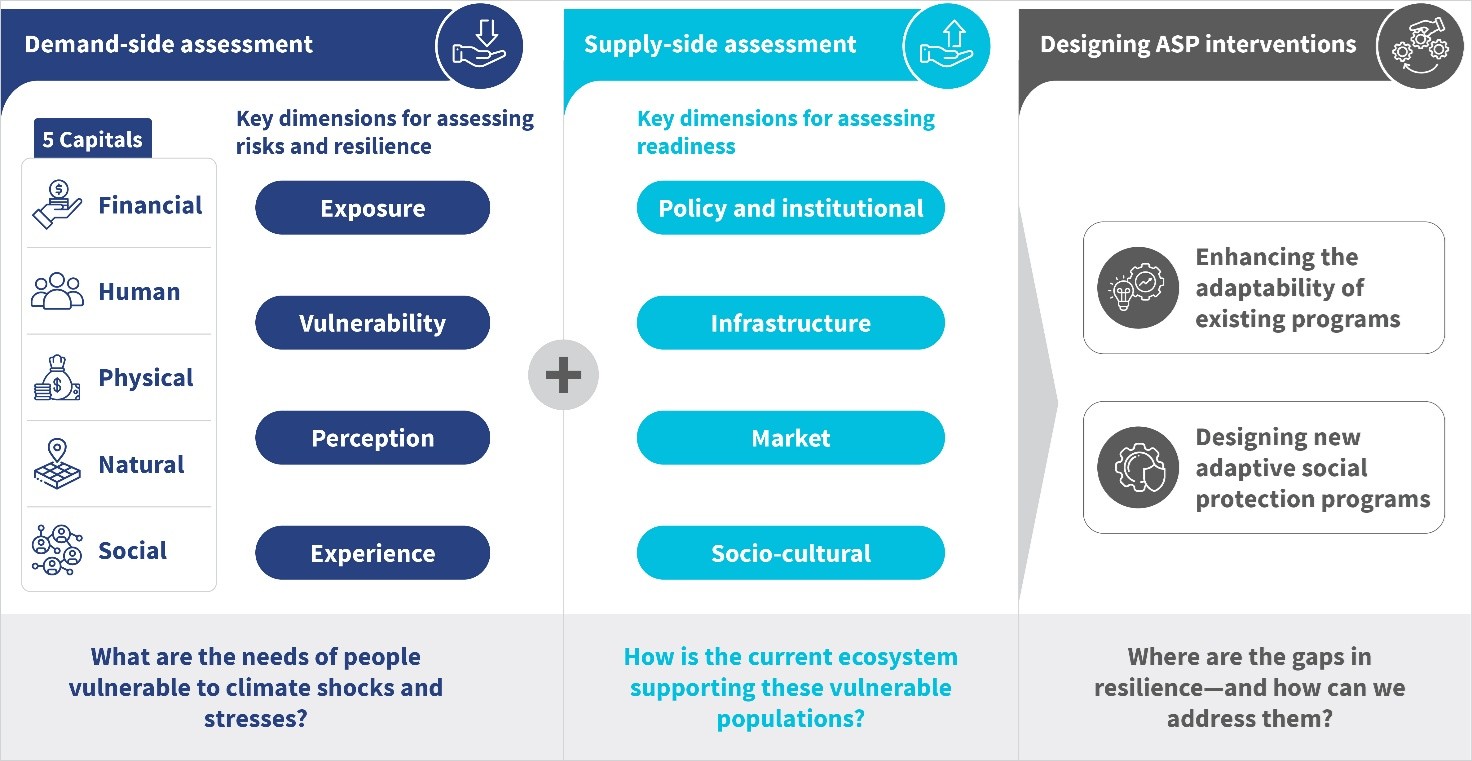

MSC’s ecosystem approach to Adaptive Social Protection (ASP) integrates social protection, disaster risk reduction, and climate adaptation to help vulnerable populations anticipate, withstand, and recover from complex risks like climate hazards and pandemics. By combining detailed demand- and supply-side analyses, this holistic methodology enables governments to identify gaps, adapt existing programs, or design new interventions that build inclusive, resilient, and responsive social protection systems.

Vulnerable people worldwide rely on social protection systems as vital lifelines. These systems include social assistance, insurance, and labor market reforms. They were traditionally built to address and manage chronic yet predictable risks, such as poverty and unemployment. Today’s world, however, presents more complex and unpredictable challenges—from climate hazards (e.g., shocks such as floods, cyclones, etc., and stresses- such as changing precipitation, rising temperatures, etc.) to other disasters, e.g., pandemics, armed conflicts, or financial crises. Such events endanger people’s lives and livelihoods while also deepening structural inequalities and persistent poverty.

As climate hazards and disasters become more frequent and severe, traditional social protection systems struggle to keep up. Adaptive Social Protection (ASP) has emerged as a response to this and intends to help vulnerable households build resilience. ASP examines and identifies strategies for ex-ante preparedness, ex-durante response, and ex-post recovery.

The need for a holistic ASP ecosystem

ASP is a comprehensive strategy that combines social protection, disaster risk reduction, and climate change adaptation. However, despite ongoing progress, some gaps remain:

- Coverage and reach: Urban vulnerability remains underrepresented in the literature on ASP. The focus on rural communities leaves gaps in addressing the specific risks urban populations face, especially those residing in informal settlements.

- Identification and access: In countries, the effective functioning of ASP is hampered by the lack of social registries or targeting issues due to outdated data, exclusion errors, and lack of interoperability. For example, the national social registry in the Philippines was not updated for four years during COVID-19, which made it unreliable for the rapid expansion of social protection programs.

- Service delivery: Manual and fragmented payment systems create delays and leakages in the transfer of benefits. ̌Evidence from a mobile money cash transfer experiment in Niger shows how manual payments add extra costs for recipeints.

- Climate adaptation: Most countries lack climate-focused social protection and rely on emergency support. The ILO reports that more than 90% of people in the 20 most climate-vulnerable countries lack any form of social protection. For example, when severe floods hit Cambodia in 2022 and people were still coping with the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the government had to rapidly extend cash transfers to address both types of shocks—pandemics and floods. Further, coverage of anticipatory cash transfers worldwide is limited, as it covers only 13 million people, with an approximate allocation of USD 200 million.

- Financial stability: For underdeveloped countries, where government spending is already constrained and borrowing from capital markets is very costly, budgetary reallocations for climate-induced shocks and stresses come at a cost. As highlighted by the ILO, little guidance is available on innovative financing mechanisms or successful examples of blended funding streams that developing countries can use to create such systems.

Considering these gaps, MSC follows an ecosystem-based approach to ASP that aims to assist governments in building robust, responsive, and inclusive social protection systems. This blog explores the rationale, methodology, and practical applications of MSC’s ecosystem approach to ASP. It draws from our experience across Asia and Africa and offers a roadmap for governments seeking resilience and equity in the face of new challenges.

The approach stands out for its holistic, evidence-based methodology. It comprehensively evaluates demand and supply aspects to help address climate hazards and disasters. The objective is to enable individuals, households, and communities to anticipate, absorb, and recover from hazards and disasters.

Demand-side analysis

On the demand side, the approach evaluates the sustainability and overall well-being of individuals, households, and communities using the five capitals approach (human, social, natural, physical, and financial). Further, it systematically examines the following four key dimensions.

- Exposure: Identifies the degree to which populations, infrastructure, and ecosystems are located in hazard-prone areas and the factors that hinder their ability to prepare, respond, and recover. It measures who or what is at risk and the extent of their exposure to potential shocks.

- Vulnerability: Understands the factors that hinder an individual or community’s ability to prepare for, respond to, and recover from climate hazards and disasters.

- Perception: Examines citizens’ perceptions of their susceptibility and preparedness and their understanding of the government’s efforts and capacity to respond to shocks, providing insights into factors like trust and awareness.

- Experience: Reviews how vulnerable populations interact with social protection programs and government disaster response programs; it focuses on accessibility, adequacy, and timeliness of services received, and highlights successes and areas for improvement in service delivery

The demand-side analysis combines these four dimensions with the five capitals approach. It offers a complete picture of the capacity of individuals, households, and communities to prepare for, cope with, and adapt to hazards and disasters.

Supply-side analysis

A comprehensive supply-side analysis systematically maps and evaluates the policies and institutional structures, infrastructure, market mechanisms, and sociocultural factors. These factors underpin a country’s capacity to support vulnerable populations and ensure inclusive, adaptive, and resilient disaster management. These four pillars are essential to understand and strengthen a nation’s disaster resilience.

- Policy and institutional readiness: This element assesses the strength and responsiveness of a country’s policies and institutions in disaster preparedness and response. It examines whether vulnerable groups are identified and protected by law and included in disaster plans and support measures. It also reviews digital public infrastructure within government systems to ensure the smooth flow of resources, information, and government-to-person (G2P) transactions during emergencies.

- Infrastructure readiness: This element evaluates the resilience of a country’s infrastructure, including the digital infrastructure, to prepare for and respond to climate hazards and other disasters. Key areas include water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) facilities, transportation and logistics networks, financial services, and telecommunications systems, all critical for effective disaster management. Additionally, with the increasing threat of epidemics and pandemics, the resilience of healthcare infrastructure is crucial to operate effectively during crises.

- Market readiness: This element looks at how market and economic systems support disaster resilience. Access to finance, agricultural productivity, and climate adaptability across agriculture and food systems are essential to ensure food security. It evaluates the capacity of industries to withstand climate hazards and other disasters to ensure resilience measures are integrated across sectors to support sustainable recovery. For example, India’s market and infrastructure readiness allowed the delivery of free food to ~800 million people during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Sociocultural readiness: the socio-cultural dynamics that influence a society’s resilience to disasters, focusing on inclusivity across race, caste, gender, and ability. It assesses how social diversity is acknowledged and supported in disaster planning, ensuring equitable protections and resources for all groups. This pillar also evaluates the trust between communities and the government and the availability of mental health and cultural support systems to aid in preparedness and recovery. Additionally, it highlights the value of indigenous knowledge, recognizing traditional practices and wisdom that can enhance disaster response and resilience strategies through locally-led adaptation.

The supply-side analysis enables governments to systematically identify gaps and bottlenecks. It pinpoints institutional, infrastructural, and market weaknesses that hinder effective disaster response. By addressing these bottlenecks, governments can strengthen the ecosystem and ensure that social protection systems are robust, inclusive, and responsive to emerging climate and disaster risks.

The design of suitable APS interventions

The demand- and supply-side analyses help us identify the gaps that affect vulnerable groups when they seek to cope with shocks and recover from them. Governments can address these gaps in one of these two ways:

- They can adapt existing programs for climate-induced shocks and stresses by expanding cash or in-kind support temporarily during shocks. The governments can use horizontal (coverage expansion) or vertical (benefit increase) mechanisms. Programs can use early warnings, such as rainfall, flood forecasts, or heatwave alerts, which would allow the government to take early actions, such as food or cash disbursement, before a disaster hits. Programs can also add climate vulnerability criteria to existing eligibility rules while creating beneficiary registries.

- They can design a new adaptive social protection program specifically designed to address climate-related risks, such as climate-linked cash transfers or adaptive public works that respond predictively to climate triggers. Programs can adjust benefits based on the severity and type of hazard, such as drought-indexed agricultural insurance, conditional cash transfers tied to livelihood diversification, or employment schemes focused on ecosystem restoration.

The path ahead

With this approach, we attempt to provide a flexible and forward-looking framework for governments and stakeholders to address the growing climate hazards and other disasters. This ensures that social protection programs are more inclusive and effective, and can evolve in response to emerging risks. Ultimately, the ASP approach empowers stakeholders to build adaptive, resilient, and equitable systems that protect the most vulnerable people, support their sustainable recovery, and nurture long-term resilience in an increasingly uncertain world.

Written by

Aarjan Dixit

Senior Manager

Akshit Saini

Associate

Mahima Dixit

Assistant Manager

Leave comments