Can design reforms improve the adoption of the Soil Health Card among India’s farmers?

by Akshit Saini and Sushma Kaw

by Akshit Saini and Sushma Kaw Sep 12, 2025

Sep 12, 2025 5 min

5 min

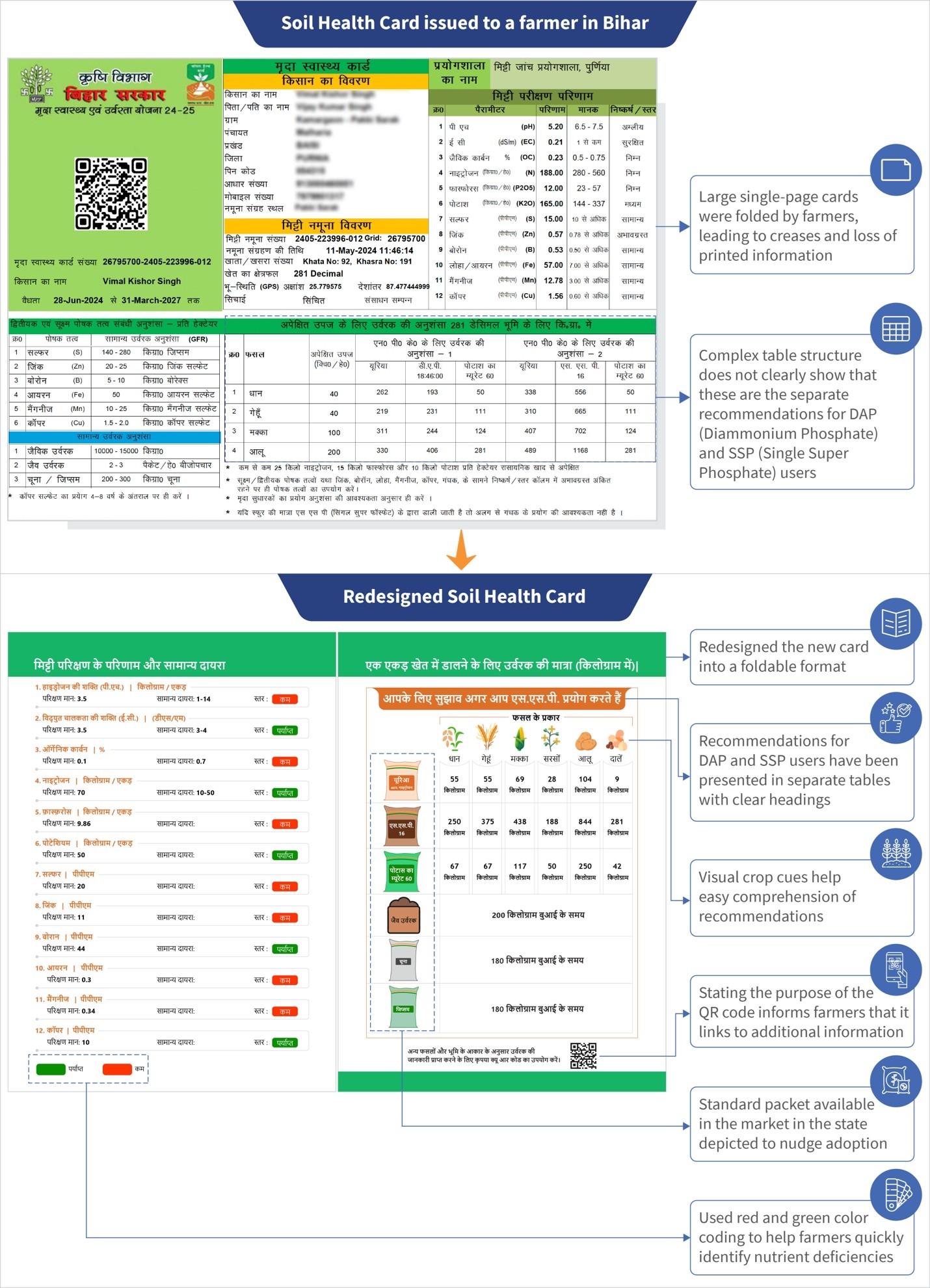

Despite its potential, the Soil Health Card (SHC) remains underutilized by many smallholder farmers in India, with its complex design being a key barrier to adoption. MSC’s human-centered redesign simplified the SHC by adding visual cues, colour-coding, local units, and a foldable format, making it far easier for farmers to interpret and apply. Yet design reforms alone are not enough. Timely distribution and strong institutional support are critical to overcoming operational hurdles and ensuring farmers receive the card in time to act on its recommendations. With the right combination of design and delivery, the SHC can become a practical tool for improving soil health and farm productivity.

Clad in a faded vest and dhoti, 53-year-old Bhagya Narayan has been farming in his little plot of land for the past 40 years. A veteran farmer from an aspirational block in India’s Bihar state, Bhagya uses a blend of traditional wisdom and modern farming techniques. He understands how optimum fertilizer use can improve soil health. When the Soil Health Card (SHC) was distributed in his block a few years ago, he could adopt its recommendations on fertilizer use with ease, which eventually improved his farm’s productivity.

However, Bhagya’s story is an exception.

For most smallholder farmers in his block, the SHC remains a missed opportunity. The SHC’s complicated terminology and layout make it difficult for the farmers to understand the card, which leaves them unsure. They do not know how to put the information into practice. The limited support from frontline agriculture officials, or even from informed farmers like Bhagya, makes many farmers set the SHC aside.

Bhagya notes, “The SHC has great value, but it is too complicated. It needs to be simplified so every farmer can derive its benefits.”

His observation reflects a nationwide challenge. A decade since its launch, around 250 million SHCs have been distributed to farmers across India. The card can potentially boost productivity, as some states recorded yield improvements of up to 40%. However, adoption is still limited due to persistent implementation hurdles. Several studies have highlighted these barriers over the years, including those by MSC and other organizations in specific states or regions. Among these challenges, the SHC’s design significantly limits its adoption.

MSC adopted a human-centered design approach to understand how farmers perceive and use the SHC to address these design barriers. We conducted focus group discussions with farmers in four aspirational blocks of Bihar and Assam. Through empathy mapping, we identified key design barriers and developed a more farmer-friendly version of the SHC.

MSC’s research revealed several barriers:

- Technical language: Many farmers struggled to understand the jargon-heavy content. For example, terms, such as pH and EC were mentioned without their full forms or explanations.

- No visual cues: The SHCs delivered nutrient results in a text-heavy format, and as a result, farmers with low literacy struggled to understand and apply the information.

- Unclear QR integration: The QR code on the SHCs was meant to give farmers access to detailed reports and crop-specific fertilizer recommendations. However, many farmers could not use the code due to a lack of clear instructions.

- Unit conversion challenges: The SHC uses hectares as a unit of measurement in the card, rather than the local units prevalent in Bihar, such as kattha or dismil. This disparity also hindered adoption.

- Bulky layout: The large single-sheet format led to frequent folding, which caused the card to wear and tear and become inconvenient to use.

These issues affect how farmers engage with the SHC, which prompted MSC to redesign the SHC with a focus on simplicity, accessibility, and practicality. MSC’s redesign incorporated several improvements. We redesigned the SHC into a foldable format, which made it more durable and easier to use frequently. The QR code featured in the card was supplemented with clear, step-by-step directions to enhance usability. Additionally, we used locally preferred land measurement units in the SHC to encourage adoption.

Figure 1: Comparison of the original and redesigned soil health card

Through an iterative redesign process, the SHC became more farmer-friendly. During feedback sessions, farmers reported that they could make sense of the redesigned card and showed greater confidence in its recommendations. One farmer remarked, “We can understand it better now. Receiving such a card from the government would be beneficial to us.

How can we unlock the SHC’s transformative potential?

Design reforms alone cannot drive change—the true potential of SHCs will be realized when farmers across the country receive accurate information at the right time alongside better support. A synchronized approach is essential to address this—one that blends timely policy implementation, upgraded infrastructure, strong farmer engagement, and more accessible design.

- Receiving the SHC: Deliver the right information on time

For the SHC to be useful, the first step is to deliver the right information at the right time. This requires a well-coordinated pipeline, from on-time soil sample collection to lab analysis, card generation, and last-mile distribution. The scheme’s operational guidelines outline a 30-day turnaround time. Samples should be collected within 10 days, analyzed in the next 10 days, and SHCs printed and distributed in the final 10 days. Block-level staff and trained personnel must be available and equipped to collect samples through standard protocols to achieve this turnaround time. Each block should also have a soil testing lab or mobile unit, with proper staff, resources, and supervision to maintain quality and turnaround times. Many farmers do not receive the card at all due to gaps in the implementation of these steps.

- Engaging with the SHC: Drive farmer engagement through community-level support

Since the card is issued once every three years, farmers need regular nudges, especially before each sowing season, to encourage healthy fertilizer use. This is why field-level engagement activities, such as periodic demonstrations, are essential. Guidelines for demonstration under the scheme rightly emphasize a participatory, farmer-facing approach. They also mandate activities, such as field days and farmer melas, to engage surrounding communities and build farmer confidence.

Implementing agencies, which include the Department of Agriculture, Krishi Vigyan Kendras (KVKs), state agricultural universities, and registered NGOs, play a key role in technical inputs, training, and support during demonstrations. Building social proof through visual comparison between SHC-applied and control plots could reinforce the idea that the SHC is a practical decision-making tool. The guidelines also recommend that subject matter specialists and farmers collaborate to conduct on-field demonstrations that compare SHC-based practices with traditional ones. MSC’s pilot study in 2018 in Krishna district, Andhra Pradesh, showed the impact of active awareness drives, where targeted messaging and local outreach significantly increased SHC adoption by farmers.

- Understanding the SHC: Reimagine the SHC design for everyday usability

Once farmers have access to the SHC and understand how to use it, the card’s design determines its usefulness. It must be easy to understand, supported by the implementation of the design reforms suggested above across all states in India. State agriculture departments must regularly review and adapt the SHCs to reflect these design principles, which would ensure the card functions as a farmer-friendly tool. In addition, artificial intelligence (AI) tools can be used to help farmers better understand the card. For instance, the Bihar Krishi app, developed by MSC, is a digital platform that provides farmers with access to essential resources and services, and uses AI to deliver SHC’s insights in easily comprehensible Hindi.

This three-step approach shows that for the SHC to reach its true potential, design improvements must go hand-in-hand with timely delivery and sustained farmer engagement. Achieving this vision will require proactive leadership from policymakers and sustained support from state-level implementing agencies. Farmers like Bhagya Narayan show that when the right information is paired with the right support, the SHC can become a powerful tool to improve soil productivity.

The redesign of the soil health card was led by Dinesh Singh, Associate Manager with the Knowledge Management Marketing team at MSC.

Written by

Akshit Saini

Associate

Leave comments