AgriStack: A DPI approach to transform Indian agriculture

by Vikram Sharma, Diganta Nayak and Kushagra Harshavardhan

by Vikram Sharma, Diganta Nayak and Kushagra Harshavardhan Nov 12, 2025

Nov 12, 2025 6 min

6 min

This blog explores how AgriStack is revolutionizing Indian agriculture through verified digital farmer IDs, mapped land records, and real-time crop data. It charts MSC’s pivotal role in the design and validation of these digital registries, consent frameworks, and data standards, which ensured inclusion, security, and tangible benefits for farmers nationwide.

An invisible crisis is strangling Indian agriculture, a sector that sustains about 40% of the country’s people and contributes 18% to its GDP. Millions of India’s farmers remain trapped in a system that does not recognize them, even though agriculture remains their main and often only identity. Farmers work tirelessly to ensure that the country’s diverse population has access to food and nutrition. Yet, it faces ongoing challenges that hold back its full potential. Low productivity from outdated farming methods, degraded soil, and fragmented landholding limit the benefits of scale. Additionally, farmers face post-harvest losses due to poor storage and weak market linkages. Price fluctuations and exploitation by middlemen also affect their earnings and financial resilience.

Tackling these issues requires stronger systems that begin with better information on farmers and their activities. Farmers often struggle to prove their identity as cultivators, the land they own, or the crops they grow, because verified and trustworthy records are missing. Databases are static, fragmented, and vary across states, which leaves farmers dependent on repeated manual checks. Without reliable real-time data, every new scheme or service requires fresh verification, making access slow and costly. This not only delays support but also increases the expense for both government and private providers. As the country grapples with climate change, population growth, and resource scarcity, digital technologies could be a transformative force.

The Indian government recognized the need for modernization and has introduced several initiatives to use technology in agriculture, one of the most significant of them being AgriStack. MSC (MicroSave Consulting) played an active role throughout this journey—from building digital registries and developing consent frameworks to piloting applications, ensuring that the system remains inclusive and that technology adoption delivers real, tangible benefits to farmers.

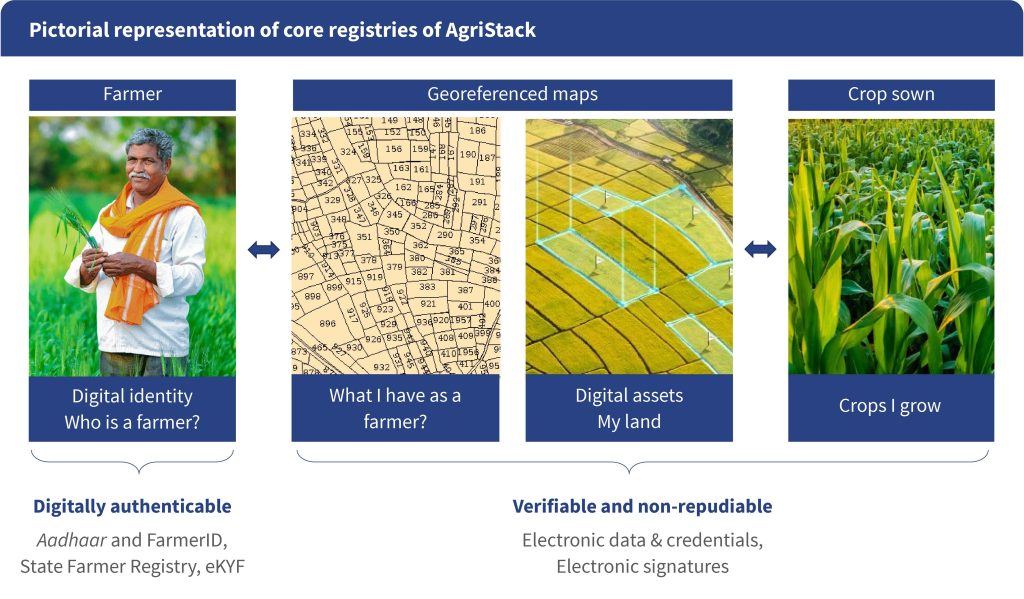

AgriStack is a federated digital public infrastructure (DPI) that comprises registries, datasets, application programming interfaces (APIs), and IT systems. It integrates digital databases and technologies to answer three core questions at the center of most issues that plague the agriculture sector:

- Who is a farmer, and what is the extent of land they own?

- Where are those land parcels located?

- What crops does the farmer grow in each season on the land parcel?

The Government of India (GoI) has created three foundational registries to answer these three questions: The state farmer registry, the georeferenced village maps registry, and the crop sown registry. These registries are the foundation that integrates stakeholders and enhances Indian agriculture through data-driven digital services. MSC supported the design and validation of these registries by collaborating with farmers, agriculture and revenue departments, and technology partners to ensure their design was practical, scalable, and responsive to on-ground realities.

- State farmer registry: This registry records details of all the farmers in the state. The state farmer registries then federate at the central level and adhere to the defined standards to create a unique farmer ID. It is a crucial building block among the three registries. The ID creates a trusted database of farmers that ensures government support, subsidies, and financial aid target the intended beneficiaries. The system assigns each farmer a unique Farmer ID, which is a digitally verifiable credential and a functional ID based on Aadhaar as per the InDEA 2.0 (India Digital Ecosystem Architecture 2.0) framework. The farmer registry uses the revenue records or Records of Rights (RoR) data foundation.[1] The system dynamically links the registry to farmers’ land records, and the system updates the ownership of the land parcel based on the mutation of the land records. The registry does not confer land ownership rights. It solely identifies farmers as beneficiaries of various agricultural services.

- Georeferenced village maps registry: This registry combines the physical village cadastral maps with geographic information system (GIS) technology to answer the second question. It integrates the land parcel information contained in the revenue records with geographic coordinates. This allows the registry to spatially represent and digitally record cadastral boundaries and related attribute data on a map. This registry maps the geographical locations of the farmers’ plots to enable accurate land tracking for customized services.

- Crop-sown registry: The registry records information on various crops that farmers sow every season for all agricultural plots across the country. It maintains a historical plot-level record of crops that farmers plant in each cropping season and creates a comprehensive record of plot-level agricultural activity. It seeks to improve and streamline the previously prevalent paper-based methods of crop survey on a sample basis, as it introduces a smartphone-based digital survey on a census basis.

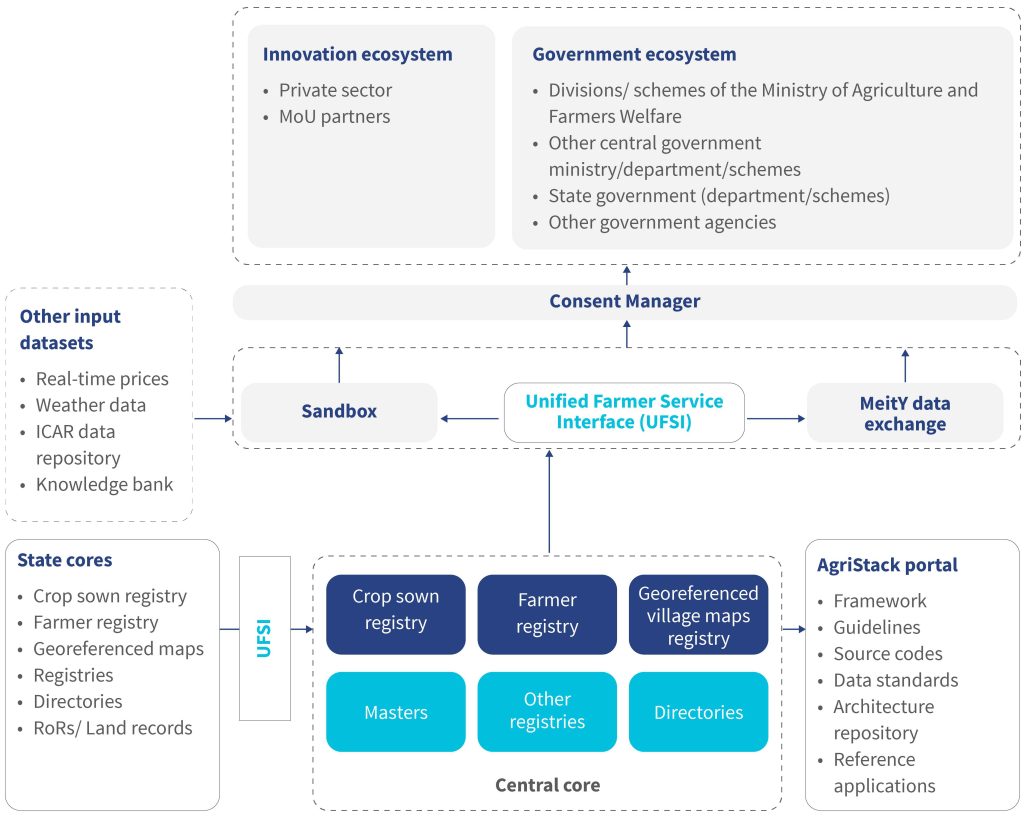

The diagram below shows how the AgriStack will function once the registries are interlinked:

The AgriStack system is based on the InDEA 2.0 principles, which include ecosystem thinking, reusable building blocks, open API standards, open-source development, and national portability. The system seamlessly integrates digital platforms across sectors to promote interoperability, innovation, and user-centric service delivery in India’s digital public infrastructure.

The AgriStack initiative is designed with a vision to simplify farmers’ access to agricultural services, which includes affordable credit, high-quality farm inputs, personalized advice, and convenient market linkages. It also seeks to streamline government planning and implementation of farmer-centric programs. The three core registries exist as the foundational building blocks of the AgriStack. Besides the three core registries, other major components of the AgriStack architecture (see Figure 1 below) include the data exchange layer called the Unified Farmer Service Interface (UFSI), consent manager, national agriculture applications, state applications, and private sector services.

Apart from the three core registries, the AgriStack architecture also integrates agricultural data from multiple sources, which include government schemes, private sector partners, market prices, weather information, and research repositories. AgriStack integrates existing systems and consolidates various services to enable farmers to access suitable assistance at the right time. The UFSI helps keep all farmers’ information organized and private, with a consent manager that ensures that data is only used with the farmer’s agreement.

The AgriStack operates as a federated system that ensures that ownership of the three registries remains with the respective states. The system has a strong focus on privacy and adheres to the Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act of 2023. Per the strict guidelines of the DPDP Act, authorized data seekers can only access data after they obtain explicit consent from the farmers.

The AgriStack follows the UIDAI’s regulations and encrypts and securely stores sensitive data, which includes Aadhaar details, in designated vaults. States strictly adhere to the guidelines established by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY) when they manage and store data to strengthen data security further. This strong consent management framework ensures data privacy, security, and transparency within the AgriStack ecosystem. MSC played a facilitative role in shaping the architecture by first supporting the definition of data schemas and the incorporation of Metadata and Data Standards (MDDS) to ensure uniformity across states, then contributing to the design of consent flows and interoperability standards that make AgriStack usable across multiple stakeholders.

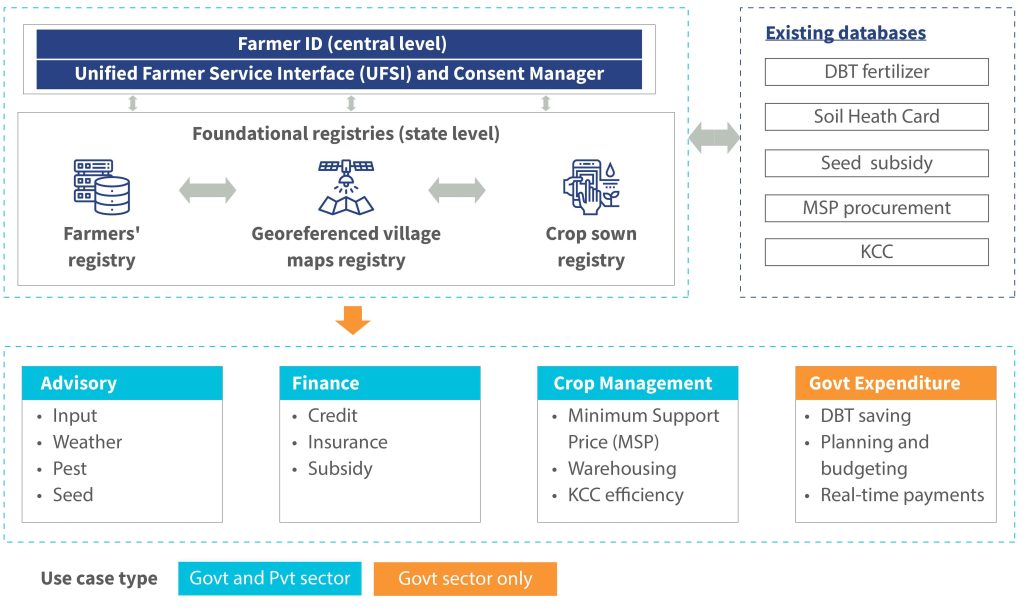

Once the AgriStack is fully developed and has access to data from public and private databases, it will create a single digital ecosystem for the agricultural sector and enable digital solutions across the entire agriculture value chain (see Figure 2). Farmers in Andhra Pradesh, Bihar, Kerala, Maharashtra, and Odisha will be able to use their digitally verifiable farmer ID issued under the AgriStack to access pre-approved, paperless credit from various public sector banks.

It will provide farmers with easier access to government programs, advice, and markets. At the same time, the government can improve the efficiency of targeted interventions. Based on the principles of AgriStack, the Government of Bihar has developed the Bihar-Krishi application as a one-stop digital platform to empower farmers with easy access to vital agricultural resources and services. Private companies can also make better data-based decisions and have more scope to develop new ideas.

We will go into further detail about the creation of the three foundational registries in the following blog posts. The first, “Building blocks of AgriStack: State farmer registry,” will explain how and why it is important to create a unified farmer registry in India. The second, “Building blocks of AgriStack: Georeferenced village maps registry,” will detail the creation of geo-referenced digital maps. The third, “Building blocks of AgriStack: Crop sown registry,” will cover the significance of a crop sown registry and how to develop one.

Leave comments