The building blocks of AgriStack – State farmer registry

by Diganta Nayak, Kushagra Harshavardhan and Vikram Sharma

by Diganta Nayak, Kushagra Harshavardhan and Vikram Sharma Nov 14, 2025

Nov 14, 2025 6 min

6 min

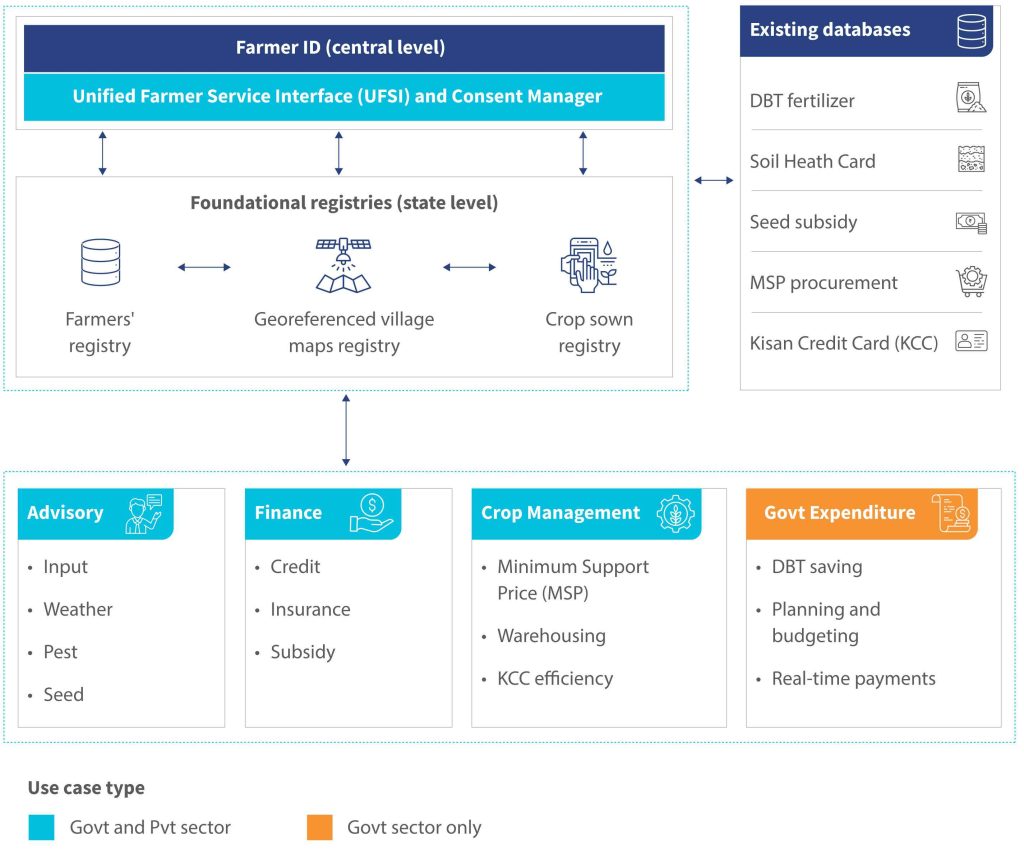

The state farmer registry under AgriStack brings every farmer into the digital fold. The registry links the farmers to verify land records through a unique farmer ID. It ensures transparency, accurate targeting of benefits, and builds the foundation for a unified digital agriculture ecosystem.

This blog builds upon our previous exploration of Agristack: A DPI approach to transform Indian agriculture. Here, we address a fundamental question that affects millions of people: Who is a farmer, and how much land do they own? This blog further examines why India needs a unified farmers’ registry and how this registry is being created.

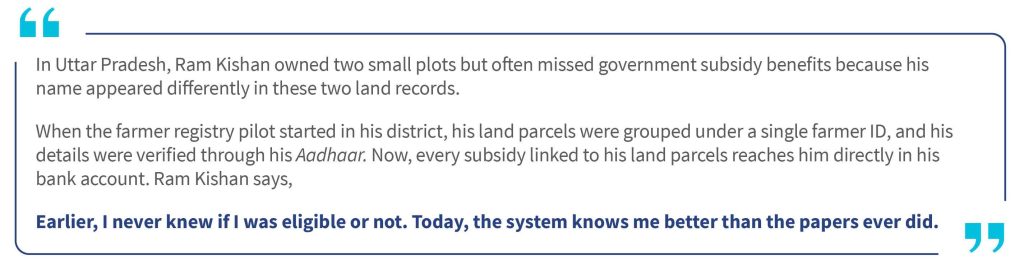

Countless farmers in India define their entire livelihood in terms of their relationship with the land. Yet, many cannot prove this relationship when it matters the most. Each government program, loan application, or support program demands fresh documentation, a cycle of manual verification that is slow, costly, and frequently ineffective. AgriStack offers a pathway to transform this, anchored on foundational registries, including the state farmer registry.

The farmer registry consists of unique farmer IDs assigned to all the owners of agricultural land parcels in the land records, often referred to as the record of rights. The farmer ID is a 10-digit number followed by a checksum digit, and it contains the farmer’s key details. These include the farmer’s name, their Aadhaar number, the plot area, and the plot number, among others, of all the land parcels owned by the farmer across the state. The farmer registry links the farmer ID with the land parcels to verify the farmer’s identity.

Currently, the farmer registry only includes land-owning farmers, despite India’s agricultural sector also comprising numerous tenant farmers and sharecroppers. It does not include those involved in allied activities, such as livestock, dairy, or fisheries. However, the Government of India plans to expand the registry to include them as well, which will ensure that all types of farmers are recognized and can access relevant government programs and services.

A comprehensive farmer registry is essential because, without it, neither the central nor the state governments have a clear understanding of who qualifies as a farmer. This leads to inefficiencies in policy planning, resource allocation, and subsidy distribution, among other areas. The struggle is even more intense for small and marginal farmers, as they face difficulties when they seek to obtain a digitally verified land ownership certificate. The absence of this certificate limits their ability to access agricultural services. This lack of reliable data also weakens the delivery of key agricultural services, such as insurance payouts, input subsidies, and credit access.

States do not currently link farmer databases to official land title records, which leads to incorrect identification of the farmers and the exact size of their land. The farmer registry will connect directly to state land title records so that there is consistency in farmer records and any change in land ownership is automatically updated for each farmer.

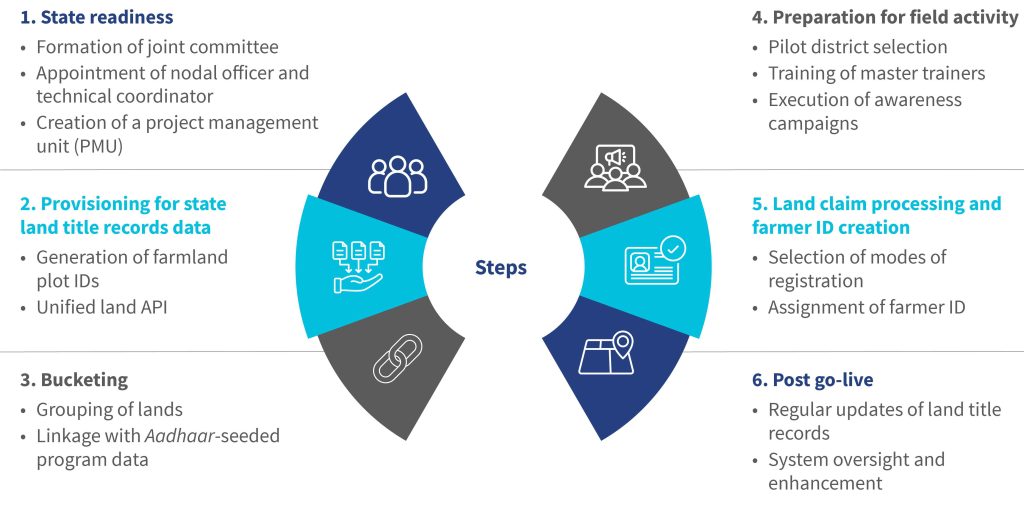

To address this, the government has outlined a six-step process for creating the farmer registry:

State readiness

Digitized land records serve as the foundation of the farmer registry. As a first step, a joint committee comprising of members from central and state governments is formed to ensure proper oversight. After this, the state government appoints a state-level nodal officer and technical coordinator to manage operations and technical needs. The government also establishes a project management unit to monitor progress and ensure adherence to timelines.

State land title records data provisioning

Next, the state assigns unique farmland plot IDs to each farmland plot in the land title records to enable accurate mapping. The majority of the states in India have developed and integrated a unified land API to transfer land title records smoothly. The unified API ensures the consistency and reliability of information across the farmer registry.

Bucketing

The state then consolidates land records within each village. It groups land parcels that belong to the same farmer for easier identification and verification. The state links data from multiple databases that are seeded with the national digital ID or Aadhaar to confirm farmer’s identity. These databases include the PM-KISAN, the cash transfer program, and the PM-FBY, the insurance program for farmers among others. This step ensures that the state can categorize lands accurately based on program data and minimizes duplication of efforts during field activities. Post bucketing, each farmer is assigned a “temporary farmer ID.”

Preparation for field activity

Pilot districts are selected to test and model the registration process, supported by trained master trainers. They lead implementation and build capacity among the field staff. The states conduct awareness campaigns to ensure widespread understanding and participation among farmers. These campaigns inform farmers about the registry, its advantages, and the registration process.

Land claim processing and farmer ID creation

Farmers claim their land buckets through self-registration, assisted registration, or by attending government camps. After registration, a farmer receives an enrolment number to monitor the status of their application in the farmer registry. State-specific policies are followed to verify the enrolment application. The policies focus on criteria, such as the name match score (NMS) and approval guidelines. NMS is essential to determine whether auto-approval is possible.The states categorize accuracy into three levels: excellent (80–100) for auto-approval, average (31–79) for manual verification, and poor (0–30) for correction before proceeding. A Farmer ID is then generated within 24 hours. Applications that do not qualify for auto-approval are subject to an on-field manual review.

Post go-live

After the registry is operational, the state should keep land title records data updated with the latest information on land ownership. Ongoing system oversight and regular enhancements ensure the accuracy of data and the effectiveness of the farmer registry over time.

The state farmer registry will build a complete farmer profile once it is integrated with the georeferenced village maps and crop-sown registry. However, India faces several challenges in developing a unified farmer registry, as land is a state subject.

The following points highlight some of these key challenges.

- Variation in the manner of maintenance of land records and taxonomy

There is significant variation in how states maintain and record land data, making it difficult to create a standard taxonomy or data format. For instance, the survey number is called “surnoc” in Karnataka and “khasra” in Uttar Pradesh. States also differ in how they record names and land details; some include aliases or salutations in the name field. Similarly, land IDs are recorded in different formats, such as 12/1 or 12-A. These inconsistencies make it challenging to electronically integrate land records, ensure data accuracy, and develop interoperable digital systems.

- Land title records are not updated in real time

The level of land records digitization and its maturity differ across states due to incomplete, inconsistent digitization and delays in updating land title records. In many cases, mutations are not linked to the digital system, causing mismatches between physical and online records. Often, the next of kin do not update ownership details after a death, and land use changes, such as conversion from agricultural to non-agricultural, are not recorded. These gaps result in outdated and unreliable land records, making accurate verification and integration difficult.

- Field verification and consent collection from the farmers

State government authorities, such as Agriculture Extension Officers, Village Revenue Officers, etc., struggle to locate farmers for field verification and collect their consent due to migration. Many people from nearby cities purchase agricultural land as an investment and are not physically present in the village. Moreover, revenue officers also do not know who owns some land parcels. These issues result in unverified farmers in the farmer registry.

- Aadhaar-linked challenges:

A farmer’s Aadhaar number is used to link all the land parcels they own. However, challenges arise when some farmers do not have an Aadhaar, such as minors or elderly individuals unable to enroll, or when their Aadhaar details, like mobile number or address, are outdated. These gaps make it difficult to link and verify land ownership records accurately.

These issues hinder efforts to verify and update the identities and addresses of farmers when state governments create the farmer registry.

In summary, the farmer registry improves transparency and targeting, but advanced features like personalized advisory services, better market access, and customized financial products are possible only when it is linked with georeferenced village maps and crop-sown registries.

Together, these form the complete building blocks of AgriStack and power a more inclusive digital ecosystem for agriculture.

-

Record of Rights (RoR): It is a document that contains essential information about land ownership, usage rights, and legal claims. It helps establish clear property rights, which makes it easier to resolve disputes, conduct property transactions, and assess land taxes.

-

Aadhaar is India’s foundational ID system for residents. It is a 12-digit number linked to biometrics and used to authenticate identity for a wide range of services.

-

Mutation means the recording in the revenue record of transfer of rights of the property from one person to others.

Leave comments