Bangladesh’s bureau reform turns repayment history into portable assets

by Alvina Zafar, Abdullah Al-Rafi and Zaki Haider

by Alvina Zafar, Abdullah Al-Rafi and Zaki Haider Dec 8, 2025

Dec 8, 2025 4 min

4 min

Bangladesh’s shift to multiple credit bureaus has emerged as a significant opportunity for stakeholders to include millions of people in the formal financial system by recognizing real repayment behavior. Read this blog to explore how the success of these bureaus depends on robust data systems, full lender participation, and the strategic use of alternative data.

For years, millions of borrowers in Bangladesh have remained invisible to the formal financial system. These borrowers include microfinance clients, informal workers, and small business owners. Their creditworthiness, demonstrated through consistent repayment in non-bank systems, has failed to earn formal recognition. This invisibility has limited opportunities for both borrowers who seek capital and lenders who look for reliable clients.

Yet, we may see an inflection point emerge in Bangladesh’s financial landscape, with Banks transitioning from the single-bureau model of the Bangladesh Bank’s Credit Information Bureau (CIB) to a multi-bureau framework. The Bangladesh Bank has issued Letters of Intent (LoIs) to Creditinfobd, TransUnion, bKash Credit, First National Credit, and City Credit, but TransUnion and bKash have chosen to form a joint venture. As a result, four private credit bureaus, namely, Creditinfo BD, the TransUnion–bKash joint entity, First National Credit, and City Credit, are now set to enter the market as CIBs.

This shift promises to democratize credit data and reorient credit assessment away from collateral and institutional ties toward actual repayment behavior. In this first part of this blog series, we examine the ecosystem-wide implications of this reform for financial service providers (FSPs), who will be instrumental in determining its success.

The problem: The CIB’s limited scope

Bangladesh’s credit information system has long relied on the Bangladesh Bank’s CIB, which provides exposure data to banks and nonbank financial institutions (NBFIs). Yet, the CIB’s coverage remains fundamentally constrained, which leaves critical segments of the economy undocumented and underserved.

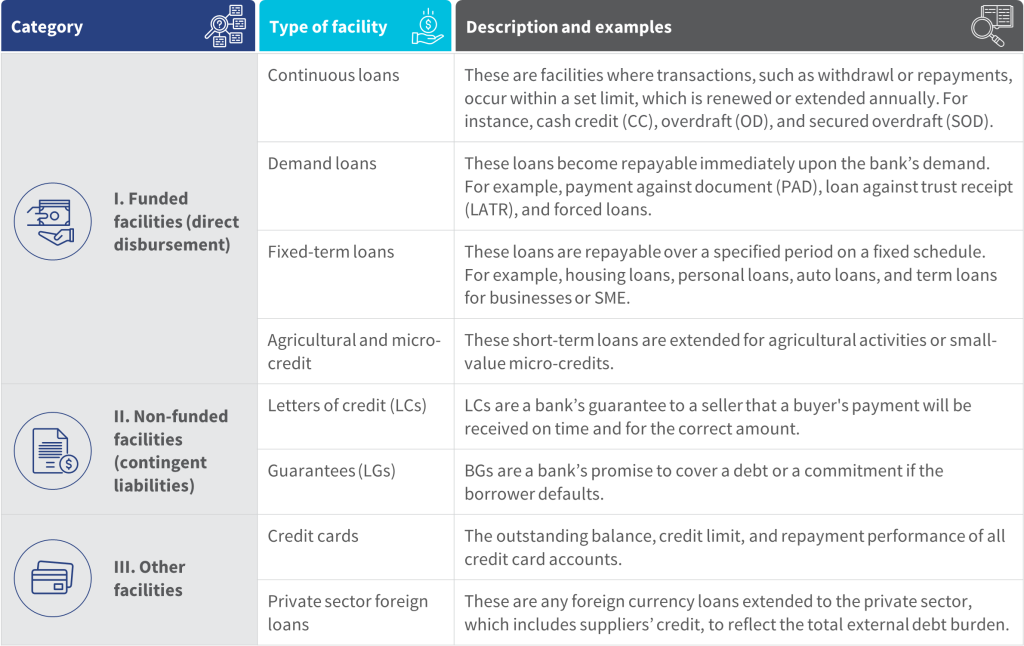

Some of the data currently captured by the CIB are listed in the table below:

Source: Bangladesh Bank

Crucially, systems, such as microfinance, cooperative lending, merchant credit, and digital credit, remain largely outside the CIB’s scope. As a result, many economically active borrowers, even those with strong repayment histories in these non-bank systems, are reduced to thin-file or no-file clients in the formal system, which renders them functionally invisible to traditional lenders.

The multi-bureau operational model as an opportunity

The four licensed private credit bureaus will fundamentally reshape access to financial inclusion by using alternative data from telecoms, utilities, and retail businesses to generate comprehensive credit scores for individuals with thin files or who are unbanked.

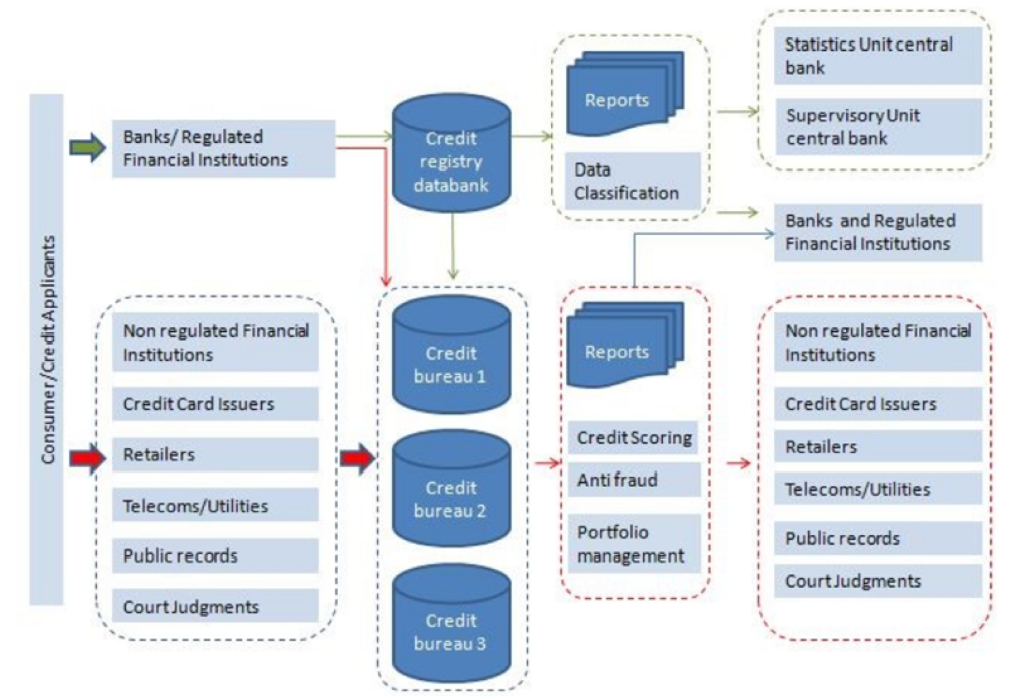

Under this new model, data flows are fundamentally restructured:

Proposed operational model of the new private credit bureau framework. Source: Bangladesh Bank’s “Guidelines on Licensing, Operation and Regulation of Credit Bureau”

The Bangladesh Bank will supervise the bureaus under the Payment and Settlement Systems Act, 2024. This new approach enables the bureaus to incorporate alternative data, such as spending patterns and low-value transactions, to build credit profiles for previously excluded segments. This structural shift introduces a critical innovation of portable credit history, which in turn supports credit ratings and improves borrowers’ ability to negotiate fairer terms.

For the first time, borrowers can accumulate “reputation collateral” that transcends individual institutions. A microfinance client’s consistent repayments, a merchant’s reliable utility payments, or a gig worker’s transaction patterns become transferable assets. This portability enables borrowers to use their financial behavior to access better credit terms, lower interest rates, and expanded financial opportunities across the formal sector.

The core challenge: foundation before innovation

Alternative data can enhance credit scoring only once comprehensive, real-time reporting of traditional credit data is completed from all formal lenders, such as banks, NBFIs, MFIs, and cooperatives. At present, Bangladesh’s credit information infrastructure suffers from critical structural weaknesses. Data updates lag by weeks or months, submissions remain incomplete across institutions, and reporting formats lack standardization. Sophisticated alternative data models built on this fragmented foundation risk the amplification of existing gaps rather than their closure.

Bangladesh must first ensure full-file, frequent, and standardized reporting across all lender types to make bureau scoring robust, supported by MIS upgrades, data-quality checks, and uniform submission protocols. Only after the core architecture is reliable can transaction-level alternative data from platforms, such as bKash, meaningfully enrich bureau models.

The shift to a multi-bureau framework represents a defining moment for Bangladesh’s financial sector. Done right, it will establish “reputation collateral” for millions of potential clients who remain invisible to traditional credit assessment, unlock new market opportunities, and drive financial inclusion at scale.

The success of this transformation to a multi-bureau framework rests squarely with FSPs. Without full participation from banks, NBFIs, MFIs, and digital lenders and without their commitment to rigorous data quality standards, the system cannot fulfill its promise. The data practices FSPs adopt today will determine whether this reform expands market access or merely redistributes existing constraints tomorrow.

This brings us to the question: How can global development partners, such as the World Bank and development finance institutions, strengthen the regulatory framework and enable this inclusive multi-bureau transition?

In Part 2 of this series, we will examine the crucial role of development partners, regulatory framework enhancements, and oversight mechanisms required to ensure the reform effectively drives upward mobility for all segments of the financial ecosystem.

Leave comments