Building blocks of AgriStack – Farm (Geo-referenced village maps) registry

by Diganta Nayak, Kushagra Harshavardhan and Vikram Sharma

by Diganta Nayak, Kushagra Harshavardhan and Vikram Sharma Nov 25, 2025

Nov 25, 2025 6 min

6 min

MSC highlights the importance of geo-referenced village map registries. These registries accurately locate land parcels, strengthen farmer identification, improve agricultural planning, and enhance service delivery. AgriStack advances through these registries and integrates spatial, ownership, and crop data, which provides better support to farmers.

As discussed in the previous blog, the state farmer registry will help identify all the farmers and the agricultural land parcels they own. Textual data on landownership is fetched digitally from the revenue records. This blog addresses the second question: Where are these agricultural land parcels located? The blog further explores the creation of a geo-referenced village map registry in India, and highlights the need to identify land locations and boundaries accurately.

Land has always been central to governance and taxation in India. The Mughals introduced early reforms, while the British later formalized systems, such as Zamindari, detailed land surveys, and revenue maps. At independence, India inherited these structures along with a reliance on manual records maintained by local revenue officials. Although these practices laid the foundation for land ownership and taxation, they also left behind fragmented and inconsistent records that continue to impact land management today.

After India’s independence, state revenue departments manually maintained land titles through local revenue officers called Patwaris. These revenue officers were responsible for managing all land rights tasks at the village level. They regularly updated the revenue records and cadastral maps after every change or “mutation”. Despite the manual maintenance of these records, the digitization of maps and records began only with the launch of the National Land Records Modernization Programme (NILRMP) in 2008.

Through the years, the Government of India has undertaken multiple initiatives to address the challenges in land records. These initiatives include Strengthening of Revenue Administration and Updating Land Records (SRA and ULR) in 1987-88, Computerization of Land Records (CLR) in 1988-89, and the National Land Record Modernization Program (NLRMP) in 2008. The most recent is the Digital India Land Records Modernization Programme (DILRMP), under which every land parcel is assigned a unique land parcel identification number (ULPIN).

The creation of a farm (geo-referenced village map) registry is essential to spatially identify and verify each land parcel boundary with geographic coordinates. This registry also supports digital crop surveys, precision advisory services, and evidence-based planning and research. For instance, in a digital crop survey, accuracy depends on the link between every land parcel in a village and its precise location on the map.This link ensures that surveyors record crop details for each plot through direct visits, rather than complete the entire survey from a single location that may even lie outside the village.

A geo-referenced village map registry enhances agricultural planning and service delivery when it links precise land boundaries with farmer and crop data. The combination of cadastral information with satellite imagery and ground truthing through GPS or drone-based surveys creates regularly updated, high-resolution spatial layers. This connection makes advisories more relevant, manages resources more efficiently, and delivers benefits to the right farmers. Key advantages include:

- Improved agricultural advisories and farm management: Integration of geo-referenced maps with geographic information system (GIS), crop registry, and weather data enables real-time, location-specific agricultural advisories. This helps farmers increase yields and resilience and supports crop monitoring, early disease detection, and resource optimization.

- Reliable land ownership information and effective land management: When digital maps are linked to the farmer registry, every land mutation or subdivision can be reflected spatially in near real time. This improves targeting, reduces disputes, and enhances transparency in land administration and the delivery of benefits.

- Data-driven policy choices and market linkages: Geo-referenced maps and integrated land–crop data support better agricultural policies, crop diversification, and precision resource planning. They also strengthen market linkages that help farmers access nearby markets, track real-time prices, and reduce dependence on intermediaries, which ultimately improves profitability.

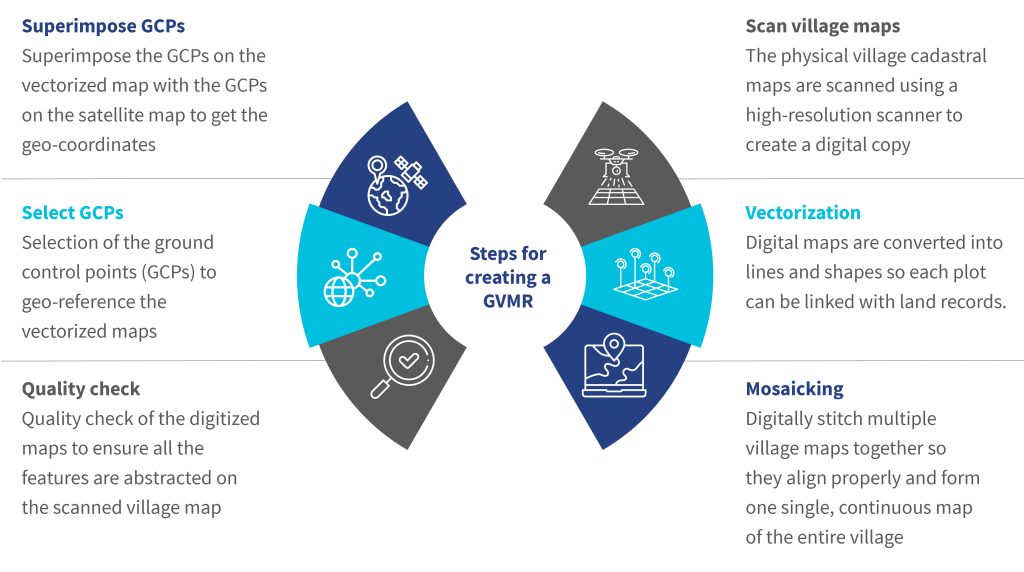

Creation of such a registry requires a series of technical and administrative steps. The ideal method is to capture fresh ground control points and physically map every individual land parcel that uses differential GPS or drone imagery. However, this is not always feasible due to costs, geographic terrain, data maturity constraints, and limited technical capacity. In such cases, states digitize the present cadastral maps and georeference them through satellite imagery. The process to digitize and georeference a village cadastral map can be broadly divided into six key steps, as outlined below:

Despite substantial government efforts, gaps persist in efforts to achieve complete digitization, integrate cadastral maps with ownership records, and update real-time geo-referenced data. It is crucial to bridge the following gaps to enhance data accuracy, interoperability, and service delivery to farmers:

- Inaccurate physical maps: Many physical land records are old and not regularly updated. The government often fails to accurately reflect the actual situation on the ground due to delays in map revisions.

- Errors in manual maintenance of maps: During manual updates of land records and maps, human errors can occur. These errors result in incorrect information being displayed on the maps about the land parcel. For example, during mutation, manual updates to maps can result in errors, such as misplaced plot boundaries or incorrectly entered survey numbers.

- Inconsistent land records: There are mismatches between the revenue records, field maps, and actual possession. These mismatches and land ownership disputes complicate land parcel ownership definition and the finalization of the digital village maps.

- Errors in scanning and vectorization: Old paper maps may be damaged, faded, or poorly aligned, which can introduce distortions during the scanning process and compromise the precision of boundary markings. Additionally, low-resolution scans produce blurry lines and illegible text, which makes precise geographic information difficult to extract during the vectorization process.

- Missing reference points in cadastral maps: Physical cadastral maps are difficult to match with actual locations since many rely on reference points. These include roads, trees, or landmarks that may have changed or vanished over time.

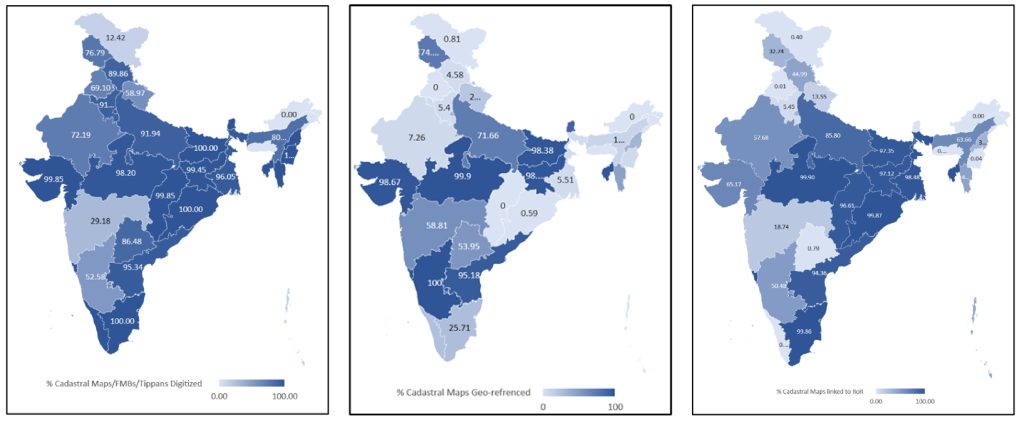

States across India have focused on efforts to digitize and geo-reference village cadastral maps through consistent mapping standards to address these challenges. This ensures spatial accuracy and interoperability across platforms. Some states have obtained high-resolution Cartosat-2 satellite images, while others have procured WorldView-2 satellite images for georeferencing.

Several states have also used drone-based mapping to capture fine-scale ground details where satellite imagery is insufficient. At the same time, a few states also conduct a special survey and settlement process to accurately depict on-ground situations and geo-reference plots. As of now, more than a dozen states have completed the digitization of all village cadastral maps and are at various stages of geo-referencing.

The integration of digitized maps with the farmer registry will provide a comprehensive profile of a farmer’s land, as the ownership data and the geo-referenced boundaries of the land parcel will be mapped to it. As part of these initiatives, Indian states have started to digitize and geo-reference village cadastral maps.

Once these digitized maps are integrated with the state farmer registry, each farmer’s landholding will have a unified spatial-textual identity. This identity combines ownership data from the revenue records with the exact digital boundaries captured through the cadastral maps. This unified record will enable instant verification of land ownership, reduce duplication, and support spatial analysis for planning and governance. Accurate, digital land maps are essential to improve farmer-focused services, such as region-specific crop insurance, customized weather updates, and location-based crop advisories.

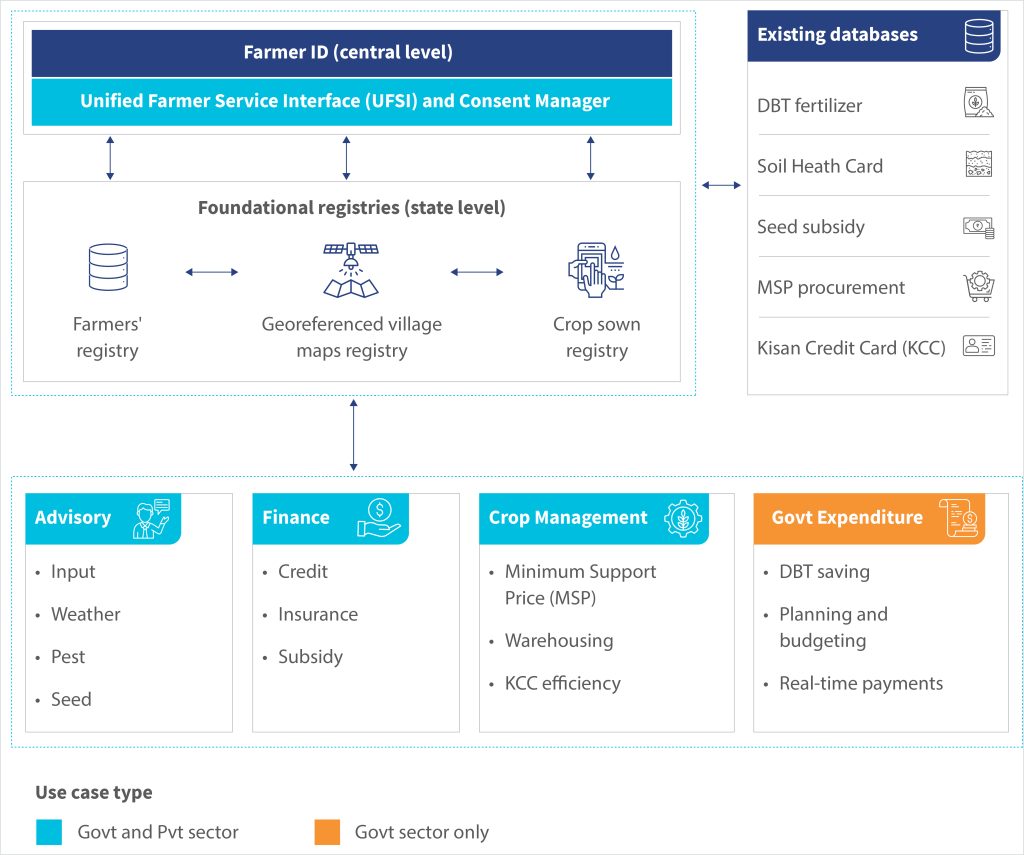

The georeferenced village maps registry along with farmer registry and crop sown registries, forms the foundation of AgriStack. Together, these foundational registries integrate spatial, ownership, and crop data to create a unified view of Indian agriculture. Once combined, these registries will support a wide range of use cases across advisory, finance, crop management, and government expenditure, which benefits public and private sector stakeholders.

The illustration below shows how the three foundational registries interact within the AgriStack ecosystem to drive this transformation.

In the next blog of this series, we will discuss the crop sown registry in more detail.

Leave comments