Building blocks of AgriStack – Crop sown registry

by Allina Tiwari, Diganta Nayak, Kushagra Harshavardhan and Vikram Sharma

by Allina Tiwari, Diganta Nayak, Kushagra Harshavardhan and Vikram Sharma Nov 25, 2025

Nov 25, 2025 6 min

6 min

India’s Digital Crop Survey and crop sown registry under AgriStack will enable accurate, standardized, and timely crop data at the plot level. Such data strengthens policymaking and improves targeted delivery of subsidies, credit, and insurance. Furthermore, it enhances farmer resilience, thus advancing MSC’s goal of data-driven agricultural transformation.

The agricultural sector in India provides livelihood support to approximately 42% of the population and accounts for 18% of the country’s GDP. With approximately 58% of India’s land dedicated to farming, it is a laborious task to track what is being grown. As per the Agriculture Census, India had nearly 146 million operational landholdings during 2015–16, each of which must be tracked to record what is planted in each cropping season.

Conventional systems of crop survey, which include Girdwari, rely on manual record-keeping methods. This system faces multiple challenges, such as approximations, memory lapses, and damaged paperwork. The Village Revenue Officials (VROs) conduct Girdawari. They record crop details, reviews, and update land records, which include ownership information and revenue assessment. Additionally, as part of the crop survey, they follow a sampling method based on grid selection by the statistics department, with grids varying based on irrigated and non-irrigated areas.

While Girdwari remains essential for administrative purposes, it has significant limitations in terms of accuracy, timeliness, and standardization. Digital records of seasonal crop sowing in agricultural plots across the country are necessary to overcome these limitations. The crop sown registry under AgriStack provides a continuous recording system that records information at different stages of cultivation. The registry maintains a historical, plot-level record of key details, such as when, where, and what crops are planted in each cropping season. It creates a detailed record of plot-level agricultural activity.

This registry serves as a national database of all crops grown in the country. It lists their scientific and regional names and assigns each a unique crop ID. At present, crop data collected by states often differ in terminology and classification. For example, the same variety of paddy or maize may be known by several local names across districts, a variation that is reflected in state-level records as well.

The Crop Registry addresses this issue through a standardized taxonomy that ensures consistent and accurate crop records. Beyond standardization, the registry supports the discovery of new varieties and hybrids. New crops that emerge through local innovation or research can be added to the database with relevant metadata. This database ensures that India’s agricultural data ecosystem remains current and inclusive.

Once these crop taxonomies are standardized, the system can improve production forecasting, crop insurance pricing, and credit access. It also enables early warning systems for crop failure. Together, these improvements enhance interoperability across digital platforms and support better coordination among stakeholders.

Built on this foundation, the Digital Crop Survey (DCS) application established the crop sown registry. The objective of the DCS is to obtain an accurate view of all crops grown on all land parcels nationwide. The application uses geofencing and AI-based image processing technology to ensure the legitimacy and reliability of data collected. This approach reshapes how farmers, government agencies, and businesses interact with agricultural data. The crop sown registry offers greater flexibility than earlier registries.

The registry also updates every crop season cycle based on the crops sown by the farmers on their plots. For every surveyed farm plot, it captures details, such as farmer ID, farm ID, village local governance code (LGD), year, cropping season, crop ID, sown area, date of sowing, and geotags.

The Government of India has developed a central reference application to conduct the DCS. States can either use the reference application or modify their existing applications to meet the technical requirements. The DCS application uses farmer and farmland data from the revenue records, along with geo-referenced village maps, to generate maps of owner plots and record crop sown information at the plot level. The village maps and farmland plot information are integrated directly into the crop survey system before each season. Once integrated with the farmer registry and the geo-referenced village map registry, it retrieves farmer details, farmland data, and geo-coordinates directly.

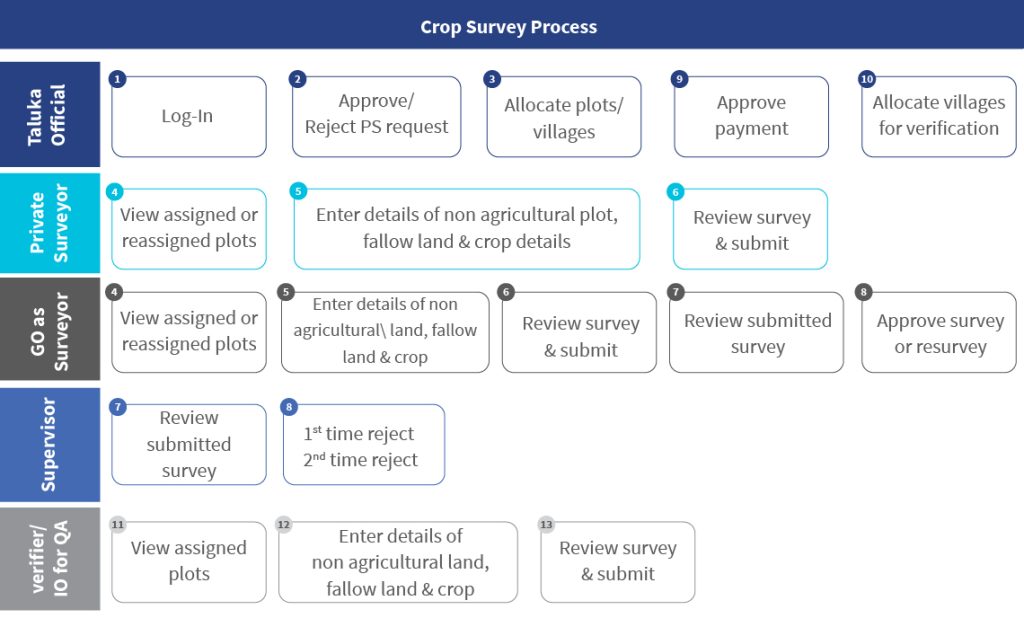

The DCS is a time-bound exercise, usually completed within 45 days of initiation. Surveyors collect and verify data in multiple stages, and supervisors review samples for quality assurance. Inspection officers also conduct mandatory checks on at least 20% of villages each season to ensure accuracy and consistency. This process ensures accuracy and consistency in the data collected. The central government or state governments will also appoint an inspection officer for quality assurance (QA). The inspection officers must perform QA checks on a minimum of 20% of the villages in each taluka every season. This layered review ensures data accuracy and consistency. This process ensures accuracy and consistency in the data collected. The central government or state governments will also appoint an inspection officer for quality assurance (QA). The inspection officers must perform QA checks on a minimum of 20% of the villages in each taluka every season. This layered review ensures data accuracy and consistency.

Despite its potential, the crop sown registry and the DCS implementation face multiple challenges that require careful planning and coordination. Some of the significant challenges are highlighted below:

- Pan-India availability of digitized and geo-referenced maps:

The biggest challenge in the creation of a crop sown registry is inconsistent geo-referencing across states. Some have precise data at the plot level, while others only map at the village level, which affects accuracy. If major shifts in geo-referencing remain unaddressed, data will be recorded against incorrect plots. Standardized nationwide geo-referencing is crucial to track crops, yields, and trends effectively.

- Complexity of land ownership issues:

One of the major issues with the digital crop survey is land ownership. There are situations where the land is in the name of a family member. Yet, the legal heir carries out cultivation. The subdivision may not reflect as a single plot on the map. Additionally, land possession often differs from the official owner listed in the record of rights. These land issues must be kept aside for crop recording. The government conducts surveys against the plot instead of the owner’s name, so in the owner’s name column, it appears like “owner of plot no. 10.”

- Complexities in crop taxonomy:

Diverse crop varieties across regions present a significant challenge due to the presence of numerous sub-varieties and hybrids. Accurate documentation requires detailed data collection, agronomic expertise, and efficient processes. Streamlined data entry, proper training, and validation are essential for accuracy.

- Integration of states with the existing DCS apps:

The integration of the DCS apps by states with existing digital survey systems, such as the MP Kisan app in Madhya Pradesh, the e-Pik Pahani in Maharashtra, or the Bele Darshak in Karnataka, poses a significant challenge. These states already have well-established and mature DCS applications, each with its unique platform, database schema, and architecture. The seamless integration of these diverse systems into a unified registry requires careful consideration and a clear migration strategy.

These challenges must be addressed to ensure reliable data for policymaking, effective resource allocation, and targeted support programs for farmers.

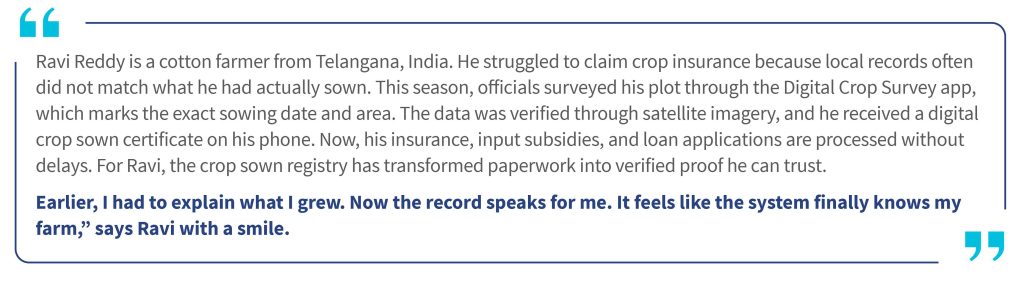

Overall, the DCS app provides farmers with digitally verified crop sown certificates, which serve as proof to avail services, such as credit, insurance, etc. These certificates also allow farmers to sell their harvest in advance at competitive procurement rates. Furthermore, the crop sown registry enables governments to estimate the market supply of various crops. This data supports decisions related to export and import as well as the allocation of food grain for industrial purposes, such as ethanol production. From a broader perspective, the system creates a win-win situation.

Over time, decisions that previously relied on estimates will be based on verified data. The crop sown registry will become a single source of truth for what India grows each season. Data consolidation and stakeholder alignment across the country pose significant challenges. Yet, the benefits of clear crop records justify the effort.

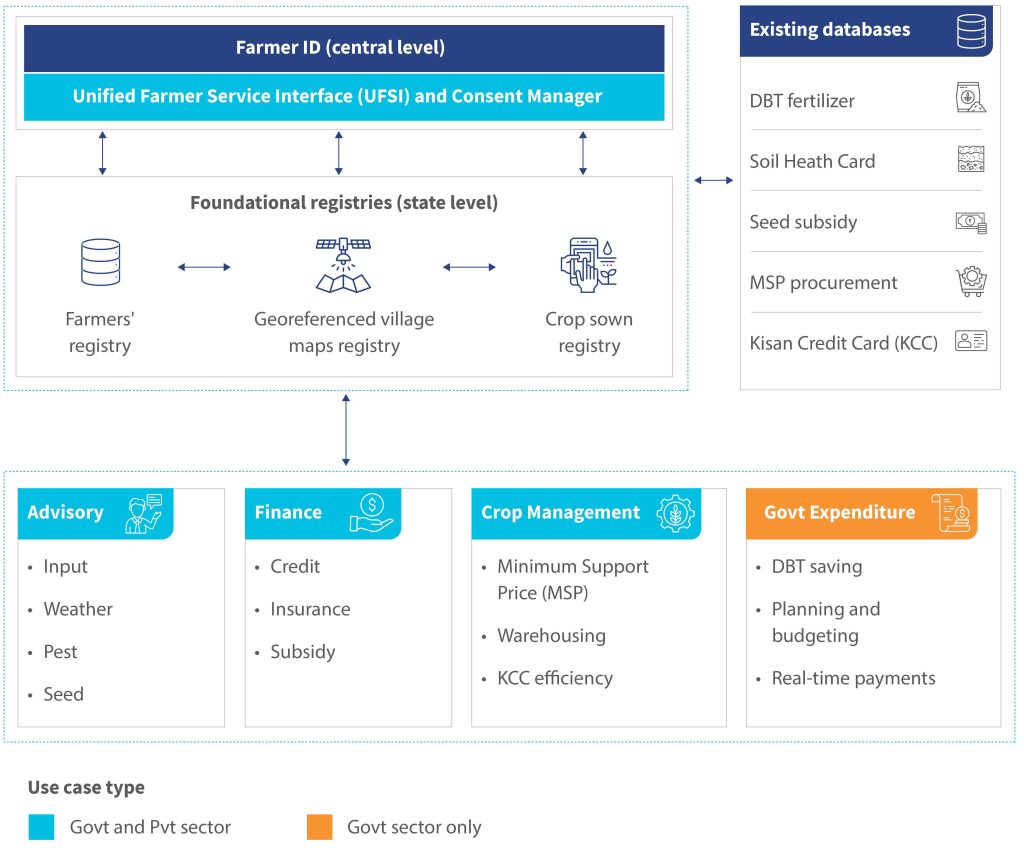

Together, the three foundational registries form the core of AgriStack. These registries interconnect to create a unified, reliable view of farmers, their land, and what they grow. When combined, they enable better planning, timely advisories, efficient delivery of benefits, and more transparent agricultural programs. The illustration below shows how these registries connect with existing databases and support a range of use cases across advisory, finance, crop management, and government expenditure.

Leave comments