Will Mobile Network Operators Make It As Payments Banks?

by Graham Wright

by Graham Wright Aug 22, 2016

Aug 22, 2016 5 min

5 min

Can Indian mobile network operators make it as Payments Banks? There is clearly a long-term business case for MNOs to open and run Payments Banks.

Of the remaining eight provisional Payments Bank licensees, four involve mobile network operators (MNOs): Airtel, Idea, Vodafone, and Reliance Jio.

This is not surprising, since successful Payments Banks will require a large footprint to serve a massive customer base, as it will be a volume game. MNOs’ existing customer base and extensive agent networks provide an important springboard to achieve and service the volumes required to break even.

Furthermore, the business case for MNOs is based not only on the revenues from payments, the margin savings accounts and other adjacent services, but also on reducing customer churn and digitising payments for airtime.

MNOs have several significant advantages as Payments Banks:

- They have established multi-layer distribution networks, with many thousands (in India’s case 1.5 million!) of retailers selling airtime and providing extensive urban and rural coverage.

- The MNO business model is based on usage (those high volumes of small value transactions), and, therefore, more aligned to the willingness and ability of the poor masses to pay in small sums; unlike the traditional bankers’ business model that is based on float. SBI’s collaboration with Reliance Jio was, in this sense, visionary – Jio can leverage the SBI brand and ability to lend, while managing the voluminous transactions on behalf of the bank.

- Mobile pre-paid platforms that manage high volumes of low-value electronic recharge are very synergistic with the needs of digital financial services. These platforms also allow the ability to offer highly customised and relevant products (supplemented with capabilities for fine segmentation and analysis of usage trends).

- MNOs have high levels of brand awareness amongst poor and rural customers that can be leveraged well for cross-selling financial services. MNOs also invest regularly and extensively in marketing and promotions to create channel and consumer awareness.

- Telecommunications is a well regulated service industry, similar to banking. Thus, mobile retailers acquiring new subscribers are well equipped to handle the Reserve Bank of India’s regulatory and compliance requirements of Payments Banks, as well as KYC norms and service activation processes.

- Telecommunications is also an investment-intensive and long gestation business. Thus, mobile operators have the capability to source funds, and make large investments with long-time horizons for returns.

- MNOs work through extensive partnerships, aggregating third-party products seamlessly into their offerings – essential for the success of digital financial services.

- Last, but quite important, because of the severe competition, price-wars, and commoditisation of voice and basic services, MNOs are highly motivated to offer stable, diversified value-added services that promise substantial upsides in terms of reduced churn, decreased airtime distribution costs, and increased revenue.

These factors (together with MNOs’ natural advantages as first movers in this market) put them in a perfect position to create the market for mass-market digital financial services.

As we concluded in a 2013 blog, Can India Achieve Financial Inclusion without the Mobile Network Operators? “MNO-led systems therefore have a hugely important role to play to create the market – to build people’s confidence in digital financial services and local agent-based systems – and thus lay the foundation for digital financial inclusion.”

When MicroSave examined the business case for MNOs as Payments Banks several additional opportunities and issues emerged. We used MicroSave’s extensive market research on the low-income segments, plus public domain documentation of MNOs in India and elsewhere, to develop detailed projections on the likely opportunities, revenues, and costs. This allowed us to build up a detailed model to examine the business case.

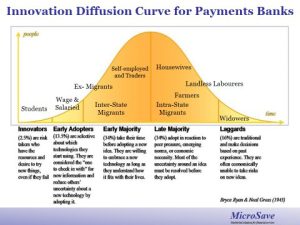

First, we examined the likely adoption patterns of key market segments (see diagram below).

On the basis of this, we mapped products for each of these segments that encompassed:

- Savings and goal-based saving

- Commitment/time deposits

- Current accounts

- B2B payments

- DBT and other G2P payments

- Utility and other bill payments

- Airtime top-ups

- Premium payments (for insurance product)

- Short-distance remittances

- Long-distance remittances

- International remittances

- Overdrafts against savings balances

- Credit products: working capital, term loan and bill discounting

- Credit score based loans

We then assessed the likely transactions, balances and other revenue sources from each of these by segment in order to build up a clear picture of the contribution of each and, thus, where MNOs should focus their efforts (see diagram below). Intra-state migrants, self-employed and traders, wage and salaried segment, and farmers are expected to yield the most revenue, but some of the initial work would be focused on students and inter-state migrants to drive adoption of these larger market segments. Thus, a carefully sequenced marketing campaign will be essential, and those MNOs already servicing the inter-state remittances market will have an important competitive advantage.

On the basis of our analysis, we expect around 90–95% of revenue to come from transactions, and only 5–10% from float. Of the 95%, the largest revenue source is likely to be remittances, transactions on basic savings accounts and shared interest on loans offered, backed by credit-scoring customers’ “digital footprints” (each around 20%). Other revenue sources will include G2P/direct benefit transfer payments and utility payments (around 10%). Airtime top-up is only expected to yield around 5–7% of the bank’s revenue, but would, of course, result in substantial savings for the MNO, in terms of both distribution costs and reduced customer churn.

On the basis of our analysis, we expect around 90–95% of revenue to come from transactions, and only 5–10% from float. Of the 95%, the largest revenue source is likely to be remittances, transactions on basic savings accounts and shared interest on loans offered, backed by credit-scoring customers’ “digital footprints” (each around 20%). Other revenue sources will include G2P/direct benefit transfer payments and utility payments (around 10%). Airtime top-up is only expected to yield around 5–7% of the bank’s revenue, but would, of course, result in substantial savings for the MNO, in terms of both distribution costs and reduced customer churn.

We then examined the operational imperatives for an MNO to build a successful Payments Bank, including the IT, branding and marketing, call centre and core employee spend, as well as the costs of agent selection, on-boarding, training, monitoring and, of course, commisions. Perhaps unsurprisingly, agent commissions and distribution operational expenses were the largest costs (in the range of 40–45% and 16–20%, respectively), followed by sales and marketing and HR costs (around 10% each).

On this basis, we built a comprehensive financial modelling of the potential for a relatively modest-sized MNO to achieve financial break-even (without factoring in the value of the expected reduced customer churn). We found that, with conservative estimates, a mid-sized MNO should break even in year 5, with an ARPU of around Rs.700–800 per customer. Importantly, the Earnings Before Interest, Taxes, Depreciation and Amortisation (EBITDA) margin grows rapidly from year 5 and is estimated to be 30–35% by year 8. We estimate the total payback period will be around 8 years, and that the internal rate of return will be 12–15% in the first 10 years.

So can mobile network operators make it as Payments Banks? There is clearly a long-term business case for MNOs to open and run Payments Banks. But, as many commentators (and indeed the Reserve Bank of India) have said, it is a long-term play, requiring significant investment. This is no different for a more traditional mobile money offering like M-PESA, MTN Money or hundreds of other mobile money offerings across the globe. Indeed, as GSMA has pointed out, seriousness of intent and significant investments are required to ensure that mobile money systems flourish and yield profits. Indeed, this is the key differentiator between mobile money deployments that “sprint” and those that “limp”. But as a Payments Bank, MNOs have significantly more options to derive revenue, particularly from transactions on, and to, the savings accounts they offer – if they are able to build and maintain a robust technological infrastructure to gain the trust of the mass market.

This blog was first published in EconomicTimes on 17th August, 2016.

Written by

Leave comments