How can digital public infrastructure improve government-to-person payments?

by Gregory Ilukwe, Kunj Daga and Subhash Singh

May 19, 2023

6 min

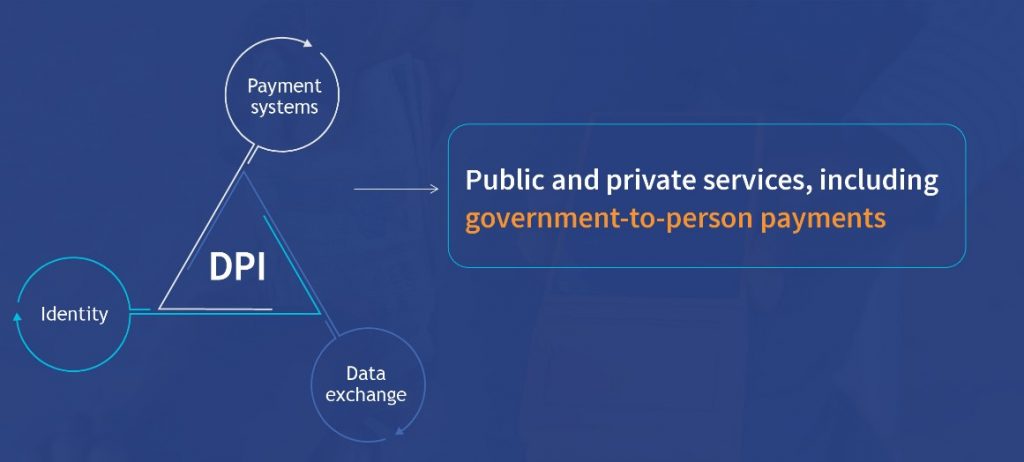

This blog helps us to understand digital public infrastructure (DPI) and its three main pillars; digital identity, payment systems, and data exchange. It explains how these pillars enable public and private service providers to deliver digital goods and services.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, millions of impoverished, at-risk individuals struggle to access essential services, such as banking, agricultural financing, and social protection. The COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the urgency of digitally delivering these services, ensuring support for individuals, businesses, and governments. Imagine living in their shoes as you navigate a world where these resources are crucial to survival.

Now imagine these services are all connected in a digital ecosystem. They are scalable, innovative, and inclusive for all. What is the cornerstone for such a digital revolution? The answer is digital public infrastructure.

Why is DBTs crossed?

Digital public infrastructure or DPI refers to digital solutions and systems that enable the delivery of society-wide services to citizens and businesses in a secure, reliable, and democratic manner. We may compare DPI to physical public infrastructure, such as highways, which facilitate travel to benefit citizens, businesses, and governments. Similarly, a repository of authentic and verifiable beneficiaries of government-to-person (G2P) payments is a DPI. It digitally enables the G2P social benefits to eligible citizens.

The implementation of DPIs has grown significantly in the past few years and enabled countries to achieve digital inclusion and empowerment for their citizens. DPIs have also created opportunities for new business models, social innovations, and public service delivery. In the coming years, they are likely to see significant growth.

DPIs are most effective when they interoperate with other systems, serve the evolving needs of their users, protect the privacy and security of users’ information, and promote innovation on top of foundational systems.

DPIs underpin a robust and inclusive digital ecosystem, and its three essential pillars are identity, data exchange, and payments. Digital identity captures citizens’ information, which uniquely identifies and authenticates them. Data exchange facilitates secure and prompt information sharing across systems. Payment systems enable seamless financial transactions. In an inclusive digital ecosystem, these three pillars help governments deliver benefits or services seamlessly to eligible citizens in an open and transparent manner.

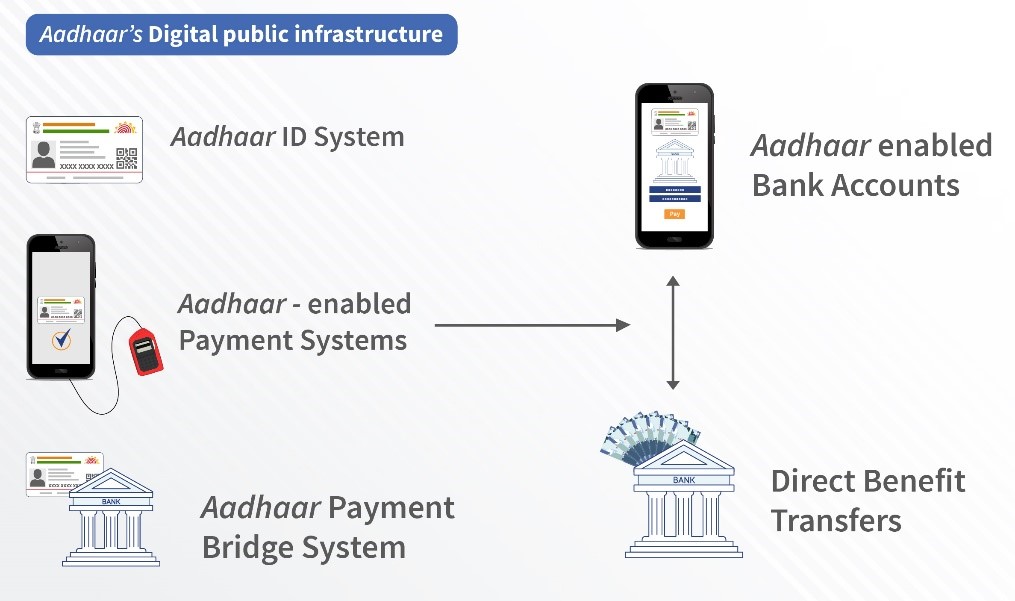

India’s digital public infrastructure

India illustrates how combining DPI’s pillars can effectively digitize G2P payments. Aadhaar, India’s foundational digital identification system, has 1.365 billion users—more than 90% of the country’s population. It captures each user’s information in a unique 12-digit ID number. The unique number’s information is shared using data exchange with service providers to enable services, such as bank account opening.

Aadhaar-enabled bank accounts (AeBA) then interoperate with the Aadhaar-enabled Payment System (AePS) to authenticate Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) beneficiaries. Then, another payment system, the Aadhaar Payment Bridge (APB) system, uses the Aadhaar number as a central key to send social benefits to the intended beneficiaries’ AeBAs. DBTs are subsidies paid directly to their beneficiaries’ accounts. Three hundred eighteen programs from 53 ministries use DBT, which accounted for 5.94 billion transactions worth a combined INR 6.24 trillion (USD 76.34 billion) in FY 2022-23.

The LPG (cooking gas) subsidy program benefitted from DPIs. The government linked subsidies directly to their beneficiaries’ bank accounts with MSC’s technical assistance. This linkage removed about 35.6 million duplicated or “ghost” beneficiary accounts from the LPG program and saved the Indian government USD 3.23 billion. The government redistributed these savings to its Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY) initiative, which benefits nearly 90 million households.

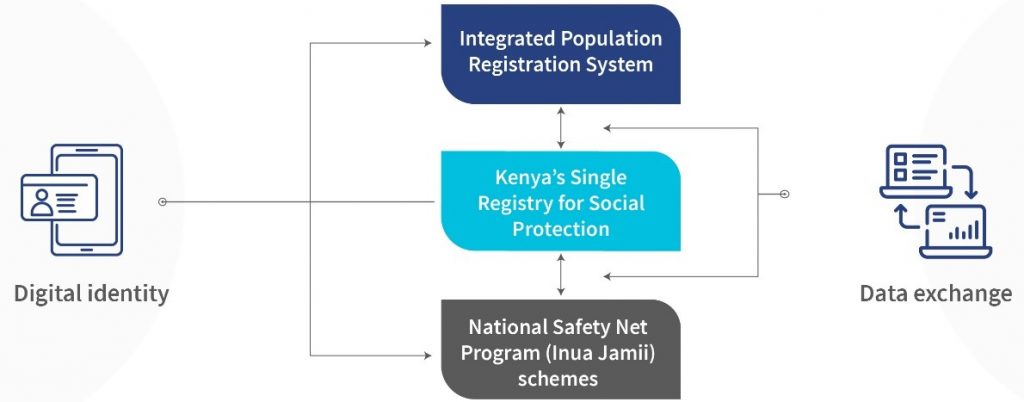

Kenya’s digital public infrastructure

Kenya’s National Safety Net Program, commonly known as Inua Jamii, is an example from East Africa to illustrate the potential for digitized G2P payments through DPI’s three pillars. Inua Jamii is an umbrella program for various transfer programs that use selected payment service providers (PSPs) to transfer social protection to beneficiaries.

Before the payments can be disturbed, the PSPs use digital identity to authenticate beneficiaries via biometric data and national ID cards. This authentication uses data exchanged between Kenya’s Single Registry, which unites beneficiary information from all Inua Jamii’s programs and its Integrated Population Registration System (IPRS). Additionally, the registry collects beneficiaries’ data during the programs, such as registration, enrolment, payments, and grievance management records. It serves as an intermediary between these programs and the IPRS.

Digital payment systems enable fund transfer from the National Treasury to the State Department for Social Protection’s Social Assistance Unit to each selected PSP and finally to the beneficiaries’ accounts using Kenya’s electronic payments infrastructure. The unique combination of these DPIs is relatively new, yet significantly, it helped the Kenyan government disburse KES 8.54 billion (USD 62.94 million) to 1.07 million beneficiaries in January 2022.

Zambia’s digital public infrastructure

Zambia’s government digitized cash-based interventions (CBI) for refugees in the Meheba Refugee settlement camp in collaboration with UNHCR, UNCDF, and MSC. The initiative registered eligible beneficiaries with SIM cards and provided them with digital wallets and PINs. Their mobile numbers and digital wallets were updated in ProGres, the government refugee database, which authenticated them before they received payments through the digital wallets.

Digitized CBI was pilot tested after MSC assessed the previous method’s challenges. Upon its implementation, 52% of CBI payments occurred using digital wallets. The distribution time was reduced from an average of 13 days to 2.5 days. This model is now used to digitize most refugee payments in Zambia.

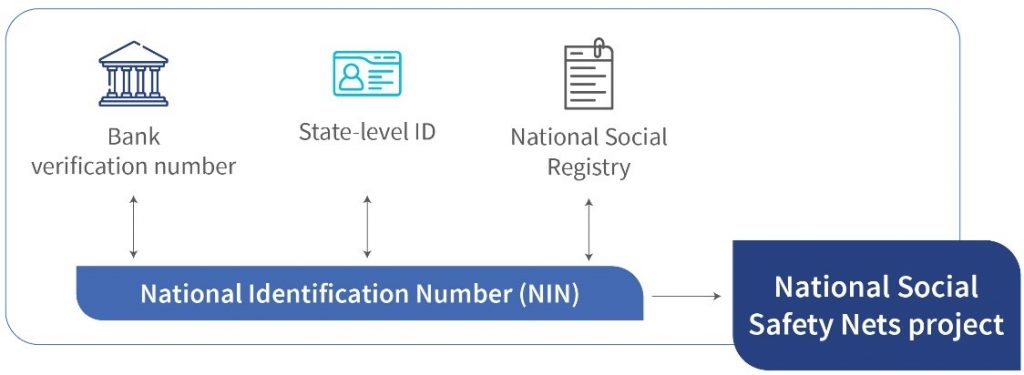

Nigeria’s DPI opportunities

Sub-Saharan Africa offers many opportunities for DPI-enhanced G2P payments, as illustrated by Nigeria’s National Social Safety Nets Project (NASSP), which contains various G2P programs. These programs store the information of their 61.6 million eligible beneficiaries in a National Social Registry (NSR). NASSP beneficiaries can be authenticated using various IDs, such as national identification numbers (NINs), state-level IDs, or bank verification numbers (BVNs), using each ID’s corresponding ID database. Then the National Cash Transfer Office (NCTO) transfers funds to select financial service providers (FSPs) via the Remita e-payment system. These FSPs credit virtual accounts that beneficiaries must cash-out from using NFC (near-field communication) cards and QR codes.

NASSP’s process has specific core infrastructural challenges. NASSP lacks a standardized ID authentication process. Nigeria’s bank verification numbers are not fully integrated into its foundational ID—the NINs. If BVNs were NIN-enabled, they could be used to open accounts for beneficiaries. Furthermore, if the NIN’s database, which has 97.5 million users, were linked to the NSR, it would streamline beneficiary authentication through data exchange between NIN, NSR, and the BVN, which has 57 million users.

Lessons, challenges, and the way forward

Cases from Sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia provide insightful lessons on the challenges within DPI-enabled G2P payments, which could help build an understanding of how DPIs can improve G2P payments. Various technologically capable parties, including government bodies, must collaborate to deliver these payments. While agent networks can provide vital assistance, G2P beneficiaries should ideally be digitally literate and equipped to receive and use payments. However, payment delivery must suit their needs and preferences.

Governments must combine identity, data exchange, and payment solutions to implement DPI-enabled G2P payments across Sub-Saharan Africa effectively. Digital identity must capture eligible beneficiaries’ information. It must combine with data exchange to integrate this information into national identity databases and authenticate these beneficiaries. Data exchange must connect with payment systems for financial service providers to give beneficiaries digital accounts that receive G2P payments. Governments and their partners must assess beneficiaries in the initial design and evolution phases, as MSC did for Indonesia’s largest digitized G2P initiative, Bantuan Pangan Non Tunai (BPNT). Additionally, governments must collaborate with the best partners to execute each phase of this process, both from the public and private sectors.

This blog raised the need to digitize G2P payments and other services for millions of impoverished individuals. In India, Indonesia, Kenya, Nigeria, Zambia, and across Sub-Saharan Africa, evidence shows that DPIs have been and will be vital to this. Solutions providers are creating DPIs, service providers are implementing them, and thought leaders are analyzing and technically assisting with them. It is time for all the players to come together, maximize their collective understanding and usage of DPIs, and create the digital revolution the impoverished millions desperately seek.

by

by  May 19, 2023

May 19, 2023 6 min

6 min

Leave comments