How Bangladesh can shift from reaction to resilience in climate finance for vulnerable communities

by Shahrukh Ahmed Latif, Farmina Hossain and Graham Wright

by Shahrukh Ahmed Latif, Farmina Hossain and Graham Wright Nov 18, 2025

Nov 18, 2025 6 min

6 min

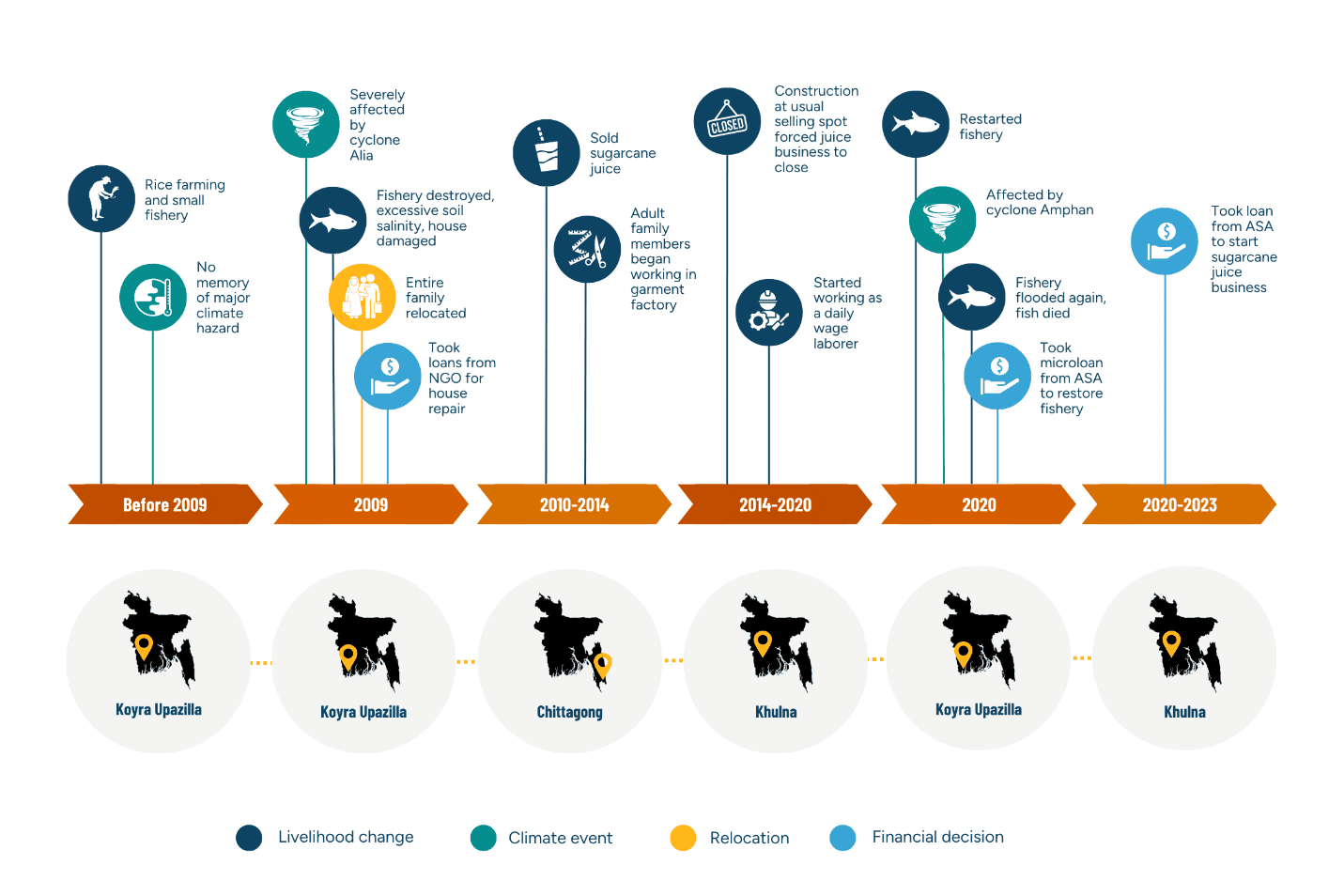

In this blog, we chart Masum’s journey, which shows how climate disasters repeatedly push families into survival mode and force them to rely on savings, loans, and informal credit. MSC’s work highlights that Bangladesh needs early, preventive, and better-designed finance to bolster the resilience of vulnerable households after climate shocks.

We met Masum Sheikh in Khulna, Bangladesh, where he sells sugarcane juice. Years ago, he lived peacefully in his native village of Koyra. There, he would grow rice and fish. Then came the fateful month of May 2009, when Cyclone Aila overran embankments, devastated his home, and inundated his fields with saline water. A desperate Masum withdrew his small savings from an informal group to cover essentials. He then borrowed from a microfinance institution (MFI) to repair his house and relocate his family to Chittagong.

(Infographic from CGAP: “Adapting to or just muddling through climate change?”)

In the new town, Masum’s wife and daughter worked in the garment industry, while he sold sugarcane juice. After four years, he used savings and another MFI loan to return to Khulna, where he opened a juice stall. When a bridge construction work started at his usual selling spot, he had to shut down his stall and work as a laborer at the construction site. Eventually, he moved back to Koyra to restart his fish farming business with the savings. Yet, bad luck followed him as Cyclone Amphan and later monsoon floods during COVID-19 in 2020 wiped out his stocks. Masum was compelled to take a loan from another MFI, ASA-Bangladesh, to restock, which he repaid and borrowed again to relaunch his juice stand in Khulna.

Masum’s story illustrates how low-income households effectively juggle informal savings and formal finance to adapt and rebuild, a strategy vital to climate resilience in a country like Bangladesh, where climate disasters, such as flooding, droughts, erratic rainfall, and cyclones, have become more frequent and destructive. For millions of vulnerable families, not unlike Masum’s, MFIs have emerged as a savior. However, much of this support remains reactive. MFIs focus on how to help communities recover from disasters rather than prepare them to withstand future shocks. Yet, these reactive measures do not enable true climate resilience.

The previous blog in this series, titled “From reactive coping to adaptive resilience amid climate change,” explored how climate-affected households adjust their financial behaviors during crises and how MFIs, such as BURO Bangladesh, step in with emergency support. This second part asks what the stakeholders can do differently to make resilience a central part of inclusive finance.

What inclusive finance providers can do

Make climate risk a credit variable

MFIs in Bangladesh should consider climate exposure as a key factor in lending decisions. Lenders can integrate hazard maps, rainfall patterns, and local vulnerability data into loan appraisals. They can design credit terms aligned with seasonal realities and regional risks. Global experience shows that this approach is both possible and practical. Global frameworks, such as the International Finance Corporation’s Climate Risk in Credit Model, help institutions link exposure to credit pricing.

Kenyan financial institutions use climate-smart credit scoring for smallholder farmers based on satellite rainfall data. NABARD in India incorporates climate-resilient appraisal frameworks into agricultural lending. Financial service providers in Bangladesh can draw from these models and strengthen their risk management systems, reduce portfolio exposure, and attract new streams of climate-aligned investment.

Shift to early-action finance

Although lending after a disaster helps families rebuild, financial lending before a disaster makes them resilient. MFIs in Bangladesh can pre-approve contingent credit lines that activate automatically when early-warning thresholds are triggered. Evidence from the World Food Programme’s Anticipatory Action Programme underscores how anticipatory lending has helped communities in 44 countries access funds before disasters. These measures reduced recovery costs and protected food security for more than 6.2 million lives.

Multiple cases from across the globe have shown that every dollar invested in pre-financing can save up to USD 34 in recovery costs. In Bangladesh, BRAC’s anticipatory loan pilot produced similar results. Atram.ai built on this momentum and is working to scale such anticipatory finance models through AI-driven tools. These tools provide early warnings and actionable financial triggers for MSMEs to help them protect their businesses before climate shocks strike.

Bundle simple, transparent insurance

For low-income households around the world, insurance coverage remains shockingly low. The Microinsurance Network’s 2023 Landscape Report found that while 330 million people worldwide have inclusive insurance, nearly 88% of vulnerable households remain uncovered.

In Kenya, ACRE Africa provides weather-index insurance linked to farm loans and mobile payouts, which reach more than 2 million farmers. In the Philippines, CARD MRI’s member-owned microinsurance network covers 32 million. Bangladesh MFIs can likewise partner with insurers and bundle index-based microinsurance with their savings and loan products.

Move from branch files to bankable pools

Aggregation will be essential to scale climate adaptation finance. MFIs can pool thousands of microloans into climate receivable portfolios. This model has already been tested through the Incofin Climate-Smart Microfinance Fund, which combines adaptive lending and insurance to attract blended capital. Development finance institutions and impact investors can provide first-loss guarantees, while insurance companies can add protection layers that cover large-scale or widespread disasters, which affect many borrowers at once.

Such blended finance instruments could crowd in commercial money without compromising client protection. In Bangladesh, similar financing structures could help institutions, such as BURO, channel funds into resilient agriculture, house elevation, and livelihood diversification of their clients.

What regulators and funders can do

Enable innovation through regulatory sandboxes

Innovation thrives when experimentation is encouraged. Several countries now use regulatory sandboxes to test climate-focused financial innovations. For example, the Reserve Bank of Fiji introduced a parametric insurance product under the UNCDF’s Pacific Insurance and Climate Adaptation Programme. The Bangladesh Bank could introduce similar climate finance sandboxes where MFIs can test out new ideas, such as parametric insurance or anticipatory credit, under simplified compliance.

Provide pre-arranged liquidity and risk-sharing

Speedy solutions can make all the difference in moments of crisis. Global initiatives show how risk-sharing and early-action finance can keep institutions afloat during climate shocks. For instance, KfW’s InsuResilience Investment Fund offers a USD 10-million contingent credit line that releases liquidity for MFIs after disasters. The IFC’s Risk Sharing Facility provides first-loss guarantees to de-risk climate lending. The Climate Risk and Early Warning Systems (CREWS) initiative supports early-warning infrastructure that links forecasts to risk-informed financial responses. Such facilities enable MFIs to continue lending even when disaster strikes, which ensures clients are not left waiting for relief.

In Bangladesh, DFIs and climate funds can accelerate crisis response if they establish standby liquidity facilities, first-loss guarantees, and reinsurance mechanisms tied to early warning systems.

Standardize data and metrics

The UNEP Adaptation Gap Report 2023 emphasizes that consistent, comparable data is essential to develop measurable climate resilience and mobilize private capital for adaptation at scale. Funders can strengthen accountability and investor confidence if they help MFIs adopt standardized metrics, such as assets protected, negative coping mechanisms avoided, or loans disbursed before impact.

Link national policy to local delivery

Climate finance strategies work best when policy supports practice. Therefore, the country’s MFIs should align national frameworks, such as Bangladesh’s National Financial Inclusion Strategy (NFIS), with grassroots implementation to ensure adaptation resources reach the communities most at risk. Coordinated action between regulators, donors, and MFIs can ensure that national ambitions translate into local resilience outcomes.

A shared responsibility for the future

The shift from reaction to resilience cannot rest on any single actor. MFIs, such as BURO Bangladesh, have shown agility and empathy in their response to crises. However, they need support to help clients anticipate and adapt to climate challenges. Regulators must provide the enabling frameworks, while funders and investors must inject catalytic capital and share risk.

Players in Bangladesh’s inclusive finance ecosystem must collaborate to anticipate risks, reduce losses, and shift from short-term coping to long-term adaptation. MFIs, regulators, and funders must shift their focus and work collaboratively to support devastated families before the next crisis hits.

Effective climate resilience will require triangulated collaboration, where MFIs deliver access; regulators create guardrails, and funders bring scale. Each of these actors can only manage symptoms if they work in isolation. Yet, together, they can transform Bangladesh’s vast inclusive-finance network into an engine of climate adaptation that can drive a safety net to protect livelihoods, strengthen communities, and empower the people most exposed to a changing climate.

Masum Sheikh and millions of climate-struck people like him in Bangladesh deserve finance networks that can shield them from climate disasters.

Written by

Shahrukh Ahmed Latif

Manager

Farmina Hossain

Director- Operations Financial Services, ICT and Human Resource Development

Leave comments