Reaching the unreached: Strengthening last-mile delivery for particularly vulnerable tribal groups (PVTGs)

by Mimansa Khanna, Saloni Gupta, Sushma Kaw and Vivek Anand

by Mimansa Khanna, Saloni Gupta, Sushma Kaw and Vivek Anand Jan 30, 2026

Jan 30, 2026 6 min

6 min

This blog unpacks why last-mile delivery often falters for particularly vulnerable tribal groups (PVTGs), showing how distance, low literacy, oral communication norms, and seasonal livelihoods shape everyday interactions with welfare and financial systems.

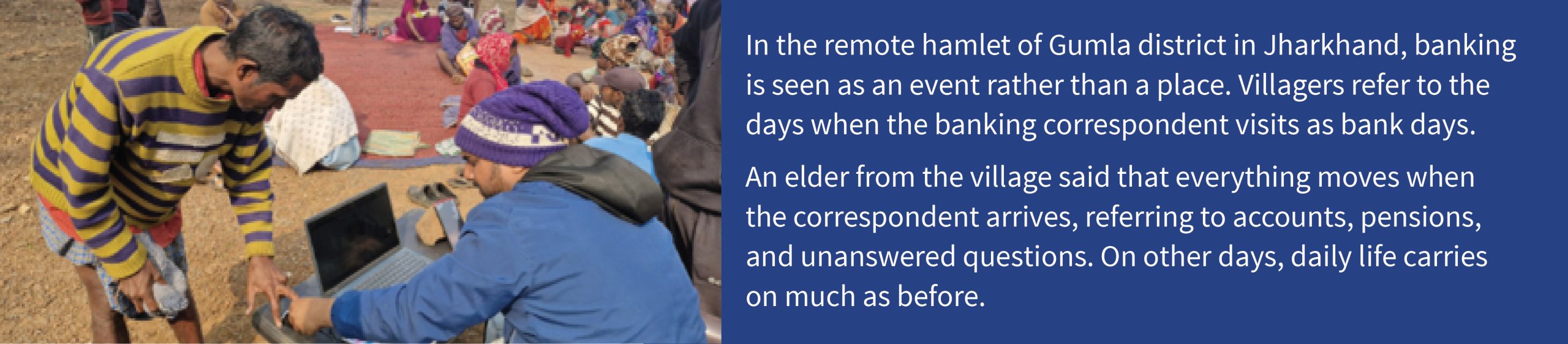

Gumla’s story highlights the importance of strengthening last-mile delivery of financial services for particularly vulnerable tribal groups (PVTG) through closer alignment with on-ground realities.

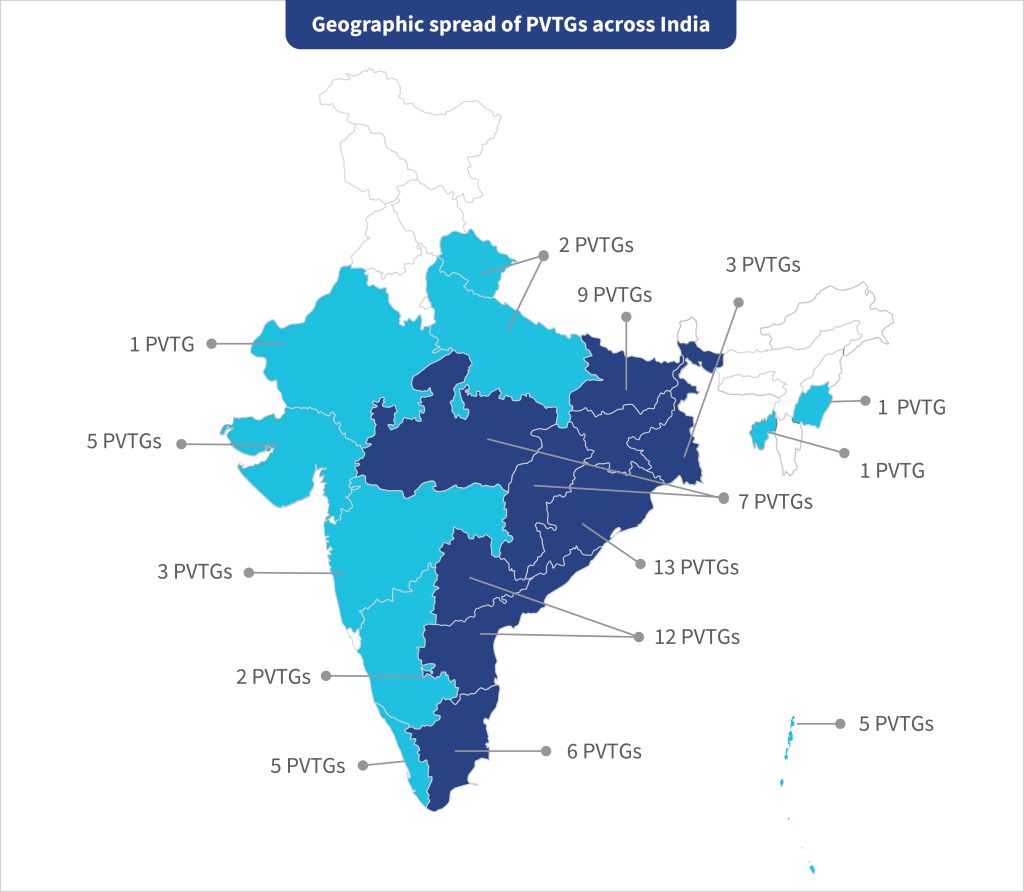

Across India’s diverse tribal landscape live 75 PVTGs, spread across 18 states and one union territory. They comprise around 2.8 million people. The Dhebar Commission first identified these communities as ‘Primitive Tribal Groups (PTGs)’ in 1973. The government reclassified them as PVTGs in 2006. These communities have low literacy levels, pre-agricultural technology, and subsistence-based economies. Often, they also have declining populations..

Over the past decade, national and state governments have intensified efforts to reach these people. The Pradhan Mantri Janjati Adivasi Nyaya Maha Abhiyan (PM-JANMAN) mission began in 2023 with an allocation in excess of INR 240 billion (approximately USD 3 billion).

The Aspirational Blocks Programme (ABP) by the NITI Aayog has generated renewed momentum in bridging historical gaps. Under ABP, block-level convergence mechanisms and locally adapted delivery approaches seek to align welfare systems with the lived realities of PVTG communities. Recent results include the completion of 136,000 houses and the establishment of piped water in more than 7,400 villages. These efforts also improved electricity and mobile connectivity.

Delivery models of welfare, financial inclusion, and social protection services often work well when people have access to regular services and can navigate written or digital processes. They run smoothly when people have standard documentation, predictable income, and stable mobility patterns. While these conditions hold in some contexts, they do not align with settings shaped by remote geographies, seasonal livelihoods, linguistic diversity, and strong community-based social structures.

MSC drew from field engagement and evidence to examine last-mile delivery of public and financial services for PVTG communities using the PACE lens, focusing on:

Delivery models encounter multiple constraints: distance, mobility, and predictability

The first layer reveals that service delivery models are anchored in formal systems. In many PVTG habitations, engagement with public systems is difficult because settlements are dispersed across forested terrain, and their mobility is dependent on their livelihoods rather than access to services. Banking infrastructure data reflects this gap between service locations of banking touchpoints and everyday mobility patterns of PVTG households. In Maharashtra, for example, nearly half of the blocks with tribal population currently lack a bank branch or ATM, and only 58% of tribal women have active accounts compared to 78% statewide.

As connectivity expands, these regions hold potential for greater participation in financial systems. Digital connectivity is gradually expanding access options. Under the 4G saturation initiative, the government covered 900 PVTG villages so far, and 500 mobile towers were installed in six months. Complementing this, BharatNet has connected more than 210,000 gram panchayats to expand digital pathways for welfare and financial services. This expansion, however, does not automatically translate into last-mile usage. In practice, whether digital services are used often depends on how transactions are perceived and socially validated at the community level. In a small market settlement of Tripura, merchants continue to prefer cash, since “with cash, the work feels complete,” as one shopkeeper noted. Seeing neighbors receive instant confirmations has helped digital tools feel increasingly dependable. Field interactions suggest that effective access depends less on services being available and more on transactions being socially verifiable- where people can see, hear, or confirm through trusted networks that payments have gone through.

When communication systems rely on text, but engagement is built on trust

Another area where service delivery becomes nuanced for PVTGs relates to how people receive and interpret information. Many public systems rely on written instructions, standard templates, and forms. In contrast, PVTG communities often prefer oral communication and rely on trusted interpersonal networks and familiar social settings.

MSC’s field experience from Muniguda block in Odisha illustrates how customized communication pathways shape engagement. In several PVTG habitations, information about banking and welfare services circulates primarily through verbal exchanges and trusted local contacts rather than written notices or formal announcements. Participation in service camps is higher when information is conveyed by familiar individuals, and lower when communication relies on impersonal or text-heavy formats.

Another hurdle is the local dialects that most households primarily speak. Literacy among PVTGs is estimated to be between 10% and 44%, whereas it is 74% nationwide. As a result, information may be technically available but not meaningfully accessible.

Initiatives, such as Bhashini, demonstrate how digital public infrastructure can support inclusive communication. This platform enables real-time translation across scheduled and tribal languages, both through speech and text. Such language-enabled platforms complement trust-based, oral communication by aligning language, medium, and messenger.

From awareness to enrolment: navigating processes on the ground

Once households decide to engage with public services, the nature of interaction shifts to process navigation. Evidence from a 10-district study in Jharkhand indicates that the Janani Suraksha Yojana did not cover 67% of PVTG women, compared to approximately 63% across India. Despite the modest difference in coverage levels, the comparison draws attention to how documentation requirements and process complexity intersect with literacy, language, and mobility constraints in PVTG contexts.

Similar observations can be seen in community-led group spaces. In Chhattisgarh, women who attend financial literacy sessions prefer seating arrangements that align with local customs. This preference for familiar settings is echoed in PVTG habitations in Jharkhand, where community meetings are most effective in open spaces rather than offices. “Here, we feel more comfortable asking questions,” a member observed. When conversations with community members move at a pace shaped by group discussion and contextually relevant set-ups, participation deepens and understanding follows naturally.

Correspondingly, women’s participation in self-help groups in several PVTG geographies remains below 15% compared to 21% nationally. These numbers highlight lower participation in formal group-based arrangements among PVTG women, pointing to the need for further analysis of how platform design and social context shape engagement.

Correspondingly, women’s participation in self-help groups in several PVTG geographies remains below 15% compared to 21% nationally. These numbers highlight lower participation in formal group-based arrangements among PVTG women, pointing to the need for further analysis of how platform design and social context shape engagement.

Open-space community meetings in Dumri block, Jharkhand, support participation in PVTG habitations

Several states are responding to these contextual factors. In Gumla district, Jharkhand, a helpline operated by a PVTG community member combines trust with practical guidance and provides Aadhaar and documentation support in the local dialect. Models, such as BC Sakhis, locally tailored NRLM financial literacy campaigns, pictorial Information, Education, Communication (IEC) materials, and community radio, similarly contribute to improved comprehension and reduced hesitation. Alongside such measures, the district also adopted an Awareness–Enrolment–Troubleshooting (AET) approach, where information dissemination is complemented by enrolment assistance and support to resolve documentation or account-related issues that emerge during access. Rather than treating engagement as a one-time interaction, this approach recognises the need for continued handholding across stages in contexts shaped by literacy, language, and mobility constraints.

Taken together, these examples illustrate how enrolment processes are being adapted on the ground through local language support and familiar social settings in select states.

Livelihood rhythms and financial engagement

Livelihood and income further shape how households engage with financial and welfare systems. For many PVTG households, incomes are seasonal, informal, and linked closely to natural cycles. They earn from forest produce, marginal farming, or daily wage labor. Therefore, even small disruptions, such as illness or delayed payments, can hurt their financial stability.

These realities shape how households interact with formal financial systems. Products designed around regular incomes and fixed repayment schedules may not always align with seasonal cash flows. As a result, households may engage cautiously or intermittently, even when access is available.

Livelihood initiatives linked to shared production offer insights into between livelihood cycles and financial engagement mechanisms can support more stable engagement. In a premium indigenous rice variety, which linked them to better markets and more predictable incomes.

Similarly, in areas where women’s SHG federations are structured around seasonal earning patterns, monthly household incomes have increased by up to 22%. These experiences show how livelihood programs grounded in local economic rhythms can help households strengthen resilience and sustain engagement with formal systems.

Similarly, in areas where women’s SHG federations are structured around seasonal earning patterns, monthly household incomes have increased by up to 22%. These experiences show how livelihood programs grounded in local economic rhythms can help households strengthen resilience and sustain engagement with formal systems.

Jeeraphool cultivation by PVTG farmers in Mahuadanr block, Jharkhand, reflects how collective livelihood platforms support more predictable incomes

Implications for policy and program design in PVTG contexts

In policy and program design, services for PVTG communities are more effective when delivery arrangements reflect local work patterns, mobility, and access constraints. Services are easier to access when they are available at right times and places, and when information is shared through trusted local channels and familiar languages. Participation is also shaped by seasonal livelihoods and limited financial buffers, which make it difficult for households to engage if services require repeated visits or loss of income. Engagement tends to be more sustained when local intermediaries support communities in navigating public systems and resolving issues over time. Across several PVTG areas, district administrations are beginning to adapt delivery approaches by combining improved access with clearer communication and practical process support, as reflected in initiatives such as PM-JANMAN and the Aspirational Districts and Blocks Programme. As a development partner under these programmes, MSC supports districts in identifying locally grounded models that help move from outreach to more consistent and meaningful participation.

Written by

Mimansa Khanna

Senior Manager

Saloni Gupta

Associate

Sushma Kaw

Manager

Leave comments