Resilience at the water’s edge: Lessons from deploying the locally led adaptation (LLA) for Inclusive financial service providers (IFSPs) toolkit in Varanasi

by Graham Wright, Aarjan Dixit, Sakshi Bansal and Manoj Yadav

by Graham Wright, Aarjan Dixit, Sakshi Bansal and Manoj Yadav Sep 26, 2025

Sep 26, 2025 5 min

5 min

In Varanasi’s weaving lanes and bustling ghats, MSMEs struggle as floods and heatwaves disrupt lives and livelihoods. Our study reveals how MSMEs adapt in fragile conditions and how inclusive finance can unlock resilience for their futures.

Perched along the mighty river Ganga, the holy city of Varanasi bustles at sunset with countless micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs). Silk weavers in their workshops, boat-makers on the ghats, flour mills, and roadside tea stalls serve as the economic heart of the region and are repositories of centuries of tradition. Yet, today, they find themselves on the frontlines of climate change.

Heatwaves, floods, and cold snaps have become increasingly common in the Varanasi district. Seasonal floods, intensified by heavy monsoon rains and river overflow, repeatedly disrupt supply chains, damage infrastructure, and erode livelihoods. Even a short interruption in work devastates MSMEs with their already razor-thin margins as it cuts their income, creates debt, or destroys businesses entirely.

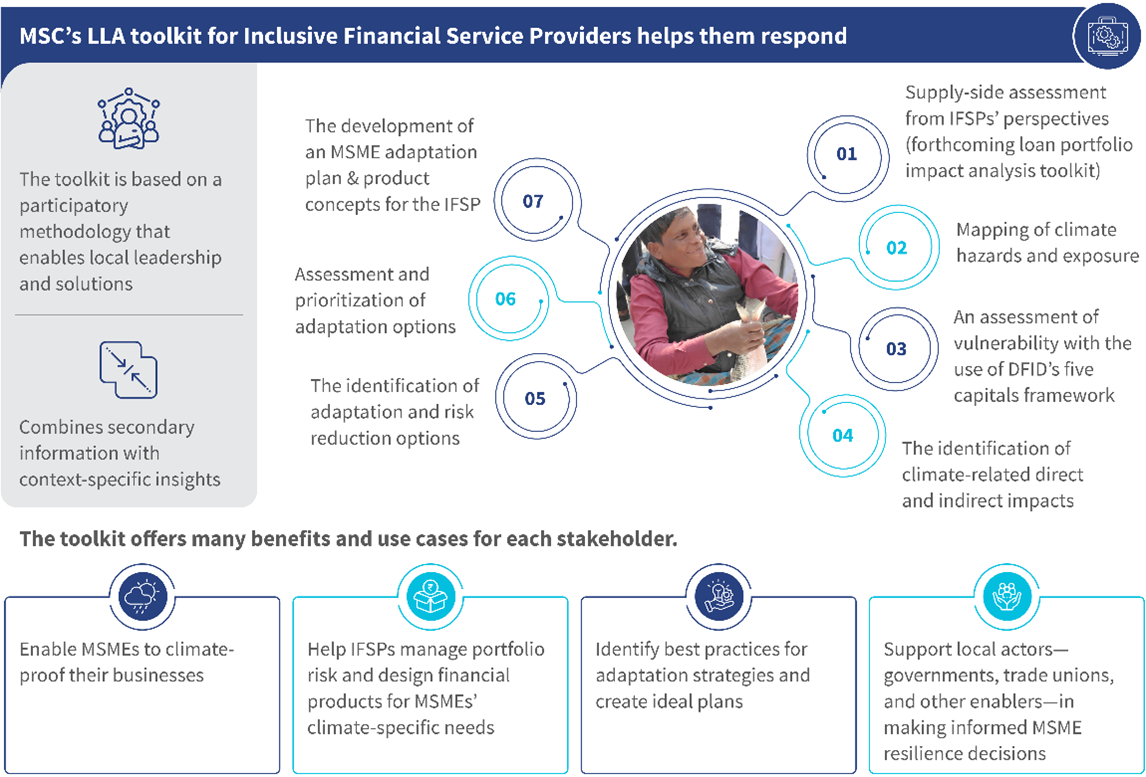

MSC sought to understand these climate risks better and explore adaptation opportunities with assistance from the Sai Institute of Rural Development. We used our Locally Led Adaptation (LLA) for Inclusive Financial Service Providers (IFSPs) Toolkit in two villages of Varanasi, Ramna and Sarai Mohana. The toolkit helps IFSPs and their MSME clients assess climate risks and cocreate adaptation strategies (see figure below). It includes six tools:

- Hazard mapping;

- Vulnerability assessment using the Department for International Development (DFID’s) five capitals framework;

- Identification of direct and indirect impacts;

- Assessment of adaptation strategies using the ACTA framework (Accept, Control, Transfer, Avoid);

- Appraisal and prioritization of adaptation options;

- Development of MSME adaptation plans and thus opportunities for IFSPs to develop, test, and deploy financial products to support them.

Our researchers held semi-structured discussions with six types of MSMEs: Shopkeepers, potters, flour mill owners, ironsmiths, weavers, and boat-makers. The findings revealed significant differences across sectors and within the same community, which underscores the importance of localized, sector-specific approaches to adaptation.

Our first stop for the study was Ramna, a village of about 3,300 people situated just 10 km south of Varanasi city. Despite some infrastructure improvements, flooding remains the dominant hazard and affects almost every enterprise.

Women entrepreneurs face particular risks. One flour mill owner, who started her business with a microfinance loan, worries that the floods will reduce the demand for flour. Floods also threaten the stability of the traditional brick structure from which she operates, possibly even the milling machine itself. Her risks go beyond the business risks and permeates into the domestic sphere where floods add dual care-giving burden to her infant alongside the responsibility to keep her mill safe. Her husband works in construction, which halts completely during floods and leaves the household doubly vulnerable. She is willing to invest in flood-proof infrastructure, but only if affordable finance is available.

Fruit and vegetable sellers face the most precarious position. Perishable stock, flooded roads, and a decline in consumer spending leave them unable to maintain their income during floods. Their adaptation strategy is to accept the risk, rely on savings, and hope for better seasons.

“Customers have no money during floods. Even if I stock goods, no one buys them,” recounts a vegetable shopkeeper from Ramna.

From Ramna, we went to Sarai Mohana, known as the “weaver’s village,” which sits precariously on the Ganga’s banks east of Varanasi. Here too, flooding is the primary hazard, but enterprises respond differently. Flooding also indirectly devastates the lives of the weavers. Although this resilient community tries to ensure safeguards against the lack of material, they face losses that threaten their livelihoods.

Beyond the looms, boat-makers on the river’s ghats face unique challenges. Power outages are common during floods, which makes it difficult to use electrical tools and lighting. Flooding disrupts orders and delays deliveries. Furthermore, any unfinished boats in low-lying areas risk being damaged or swept away.

Boat-makers seek to avoid the risk in response. When they have adequate advanced warning of impending floods, they relocate raw materials to safer areas and try to complete orders before peak floods. Yet, they cannot invest in better tools or more resilient infrastructure without formal credit. Their adaptations remain piecemeal and self-funded.

What the toolkit revealed

Several patterns emerged across both villages. Although floods are seen as inevitable, their impacts vary by sector. MSMEs from different sectors face the same hazards but respond differently due to variations in supply chains, financial models, and operational structures. Shopkeepers struggle with direct damage to goods and infrastructure, while potters and weavers suffer supply chain disruptions. Boat-makers deal more with fluctuating demand than with direct losses.

“Flooding is the same for all of us, but it breaks our work in different ways,” laments a boat-maker from Sarai Mohana.

Most MSMEs have weak physical capital, especially shopkeepers and potters who work in fragile stalls and mud-based structures vulnerable to rising waters. Most MSMEs we interviewed reported limited financial capital, while their enterprises rely on daily cash flows and minimal savings. Social networks provide some support to microentrepreneurs in Ramna, but seem weaker in Sarai Mohana, where floods affect everyone equally. Human capital is under strain as younger generations increasingly leave traditional trades and head to the city for better livelihood opportunities.

Most entrepreneurs are resigned to their fate and accept the drastic changes that floods wreak on their operations. Adaptation strategies often fall under “accept.” Few entrepreneurs transfer risk through insurance or access credit for resilience. Most cope through informal means, with low-cost “control” measures to minimize the damage. They relocate shops, stockpile materials, or diversify their income sources. We found little evidence of long-term planning or capability to finance it.

Lessons for IFSPs

The Varanasi pilot highlights the urgent need to bridge MSMEs’ adaptation needs with customized financial solutions. For IFSPs, the insights are clear:

- Recognize adaptation as bankable: Just as we learned how boreholes or feed reserves transformed lives in Uganda, flood-proof structures, improved storage, or resilient equipment should be seen as logical and valuable investments in Varanasi.

- Design flexible products: Seasonal repayment schedules and affordable loans for minor infrastructure upgrades could enable key adaptation strategies.

- Bundle finance with services: Loans linked to technical advice, collective procurement, weather forecasts, and group insurance programs could enhance resilience and reduce portfolio risk.

- Segment MSMEs by sector: Different MSMEs face the same hazard but at various points in their supply chains. Sector-focused financial products, whether for weavers, potters, or boat-makers, will be more relevant and practical than generic credit products.

From flood risk to financial resilience

Our research in Varanasi highlighted that MSMEs are well aware of the risks they face. They know floods will come, if not always exactly when. They understand where their vulnerabilities lie and already use the short-term coping mechanisms outlined above. Yet, they lack financial support to move from simple coping to planning and management. This is why they cannot move from acceptance to robust adaptation and resilience.

As one potter put it, “We know the floods will come. The question is whether our work will survive them.”

For IFSPs, risk management is both a challenge and an opportunity. Ignoring climate risks threatens loan portfolios and constrains MSME growth. However, by integrating locally led insights into product design, IFSPs can catalyze adaptation and resilience and transform MSMEs into active partners in climate adaptation. The MSMEs of Varanasi cannot afford to wait. Their survival depends on financial products that acknowledge climate realities.

Leave comments