Enhancing the financial health of women-owned microenterprises (WMEs) in South Africa

by Jeanne Nganga, Priscilla Okutoyi, Kim Kariuki, Shirleen Olalo and Lois Adongo

by Jeanne Nganga, Priscilla Okutoyi, Kim Kariuki, Shirleen Olalo and Lois Adongo Feb 25, 2025

Feb 25, 2025 6 min

6 min

In this blog, we explore the financial health of women-owned microenterprises (WMEs) in South Africa. The blog highlights the key challenges WMEs encounter when they seek to achieve business growth. It goes on to recommend sector-specific interventions, financial education, and tailored financial tools to improve resilience.

A tale of grit and growth

Zanele, a 25-year-old woman from Soweto, exemplifies the resilience of many women entrepreneurs in Gauteng. She runs a small spaza shop that supports her four younger siblings and contributes to the local community. Zanele inherited the shop two years ago after her mother passed away, and used up all her modest savings to sustain the business. In common with 43% of WMEs in South Africa, Zanele relies on informal loans with high interest rates, eroding her already thin profit margins. For her, survival means keeping the shop open to feed her family, often at the expense of potential business growth.

Thandiwe, a 34-year-old beauty salon owner in Mamelodi, turned her dream into reality four years ago after completing beauty school. Though her business is formalized, she faces challenges managing cash flow and separating personal and business finances.

At 45, Gugu represents the aspirations of a growth-oriented entrepreneur. She runs a successful catering business and recently diversified into construction. Unlike Zanele and Thandiwe, Gugu maintains disciplined financial management, separates personal and business finances, and leverages formal bank loans to drive growth. Her approach demonstrates how strategic financial practices can unlock opportunities for reinvestment and expansion.

These women’s stories reflect broader trends among WMEs in South Africa. Despite their diverse circumstances, they all navigate significant barriers to financial health and business growth while contributing meaningfully to their communities.

Women entrepreneurs: Driving South Africa’s economy forward

South Africa has 2.6 million micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) that contribute 40% to its GDP. Women-owned microenterprises (WMEs) comprise 46% of these MSMEs. Yet, they stare at a staggering USD 6-billion gap in finance due to limited access to formal financial services, gender biases, informal operations, and the COVID-19 pandemic’s lingering effects.

MSC interviewed 600 WMEs in four districts of Gauteng—Johannesburg, Pretoria, East Rand, and West Rand—to uncover the determinants of their financial health. This blog sheds light on our research findings, explores the diverse financial realities of women entrepreneurs, and highlights ways to enhance their financial resilience.

Understanding WMEs’ journeys

Our findings revealed that 87% of WMEs in the trading sector are not registered, which limits their scalability. Informal operations restrict access to critical government support and hinder growth due to difficulty securing clients and partnerships.

Financial management issues worsen these challenges. Nearly half the WMEs surveyed do not separate personal and business finances. While 55% of them find it easier to manage cash flow this way, 48% want to avoid the costs of separate accounts. These practices hinder cash flow management, financial planning, and thus sustainable business growth. Additionally, savings and investments are the most widely used financial tools, especially in manufacturing, where WMEs achieve higher revenues and profits.

Our research uncovered the following three WME segments based on their businesses’ financial health:

- Determined survivalists: Zanele, a 25-year-old woman from Soweto, personifies this segment. She runs a small spaza (informal shop) to support her four younger siblings. She inherited the business from her mother and used her savings to sustain it. Like 43% of WMEs in South Africa, she too depends on high-interest informal loans, which erode her profit margins. Zanele seeks household stability. Her focus is on survival rather than growth. Entrepreneurs in this segment prioritize simplicity and often mix personal and business finances. This group has the lowest earnings.

- Strategic optimizers: Thandiwe, a 34-year-old beauty salon owner in Mamelodi, represents this segment. She formalized her business after she completed beauty school. Despite this, she struggles to manage cash flow and separate her personal and business finances. Entrepreneurs in this segment seek operational efficiency and moderate growth. They manage finances well and use available resources, such as state funds, digital tools, and skilled human capital.

- Growth seekers: People in this segment pursue ambitious expansion. At 45, Gugu exemplifies a growth-oriented entrepreneur. She runs a successful catering business and has diversified into construction. Unlike Zanele and Thandiwe, she follows disciplined financial management, separates business and personal finances, and secures formal bank loans for expansion. Her approach showcases the benefits of structured financial practices. Entrepreneurs in this segment have the highest earnings and assets.

The table below gives a detailed insight into the financial behavior of these three segments.

Key challenges WMEs face

These personas face diverse challenges and opportunities, which emphasize the need for tailored support to meet their needs.

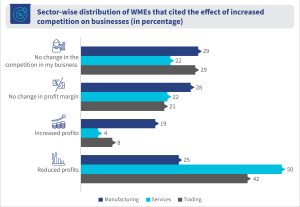

- Competition: In the service sector, more than 50% of WMEs report declining profits due to market saturation. In contrast, the manufacturing sector uses higher revenue streams, asset bases, and customer diversification to withstand competition. These findings suggest the need for sector-specific interventions to enhance resilience and profitability.

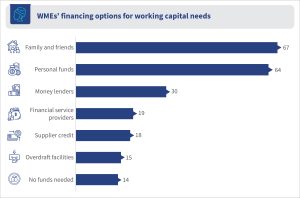

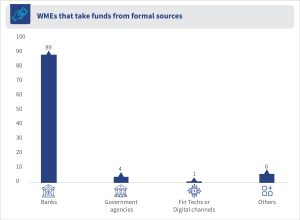

- Financial access: Access to affordable, timely credit remains a tall hurdle. Many WMEs rely on personal funds or informal networks for working capital and prefer banks for formal borrowing. Despite the growing availability of digital financial solutions, adoption is low as people lack awareness, struggle to navigate digital platforms, and distrust formal institutions.

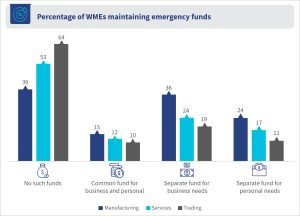

- Financial management and resilience: MSC’s research found that more than 64% of WMEs in the trading sector lack financial safety nets, which makes them vulnerable to economic shocks. In contrast, 36% of manufacturing WMEs maintain separate business emergency funds, which reflects stronger financial management.

Across all three sectors surveyed, only 11% to 24% of WMEs set aside personal emergency funds. While savings remain a primary funding source, emergency funds become more prevalent as WMEs progress from determined survivalists to strategic optimizers and growth seekers.

- Business management: Strong business acumen determes WMEs’ success. For instance, Gugu’s catering business flourished due to her ability to manage cash flow, reinvest profits, and secure long-term contracts. However, many WMEs across sectors struggle with cash flow and financial management.

Our research highlights varying recordkeeping practices. Better recordkeeping can enhance financial planning, facilitate access to credit, and support overall sustainability. Yet, while 99% of WMEs in manufacturing keep written records, only 72% of WMEs in trading follow the same practices. This gap underscores the opportunity to improve administrative practices, particularly in sectors with lower recordkeeping rates.

The infographic below summarizes challenges WMEs face at different stages of their lifecycle:

The road ahead for inclusive growth

Financial education and entrepreneurial training are critical to equip WMEs with the business skills to ensure better credit management and business sustainability. Course content should cater to diverse learner personas. It should start with foundational concepts and then increase in complexity. The course can also use gamification to enhance engagement. A centralized course-tracking platform can reduce duplication of course content and help financial service providers underwrite credit facilities by disbursing facilities to borrowers with an understanding of the facility.

MSC’s research on the financial health of WMEs indicates the importance of culturally relevant financial education. Partnerships with local NGOs and the private sector can improve dissemination and ensure that training materials reflect the social and economic realities of WMEs and address biases related to race and class. Blended delivery methods, which include digital and in-person sessions, are vital. The use of local language, local case studies, and local tutors can improve the relatability of the materials delivered. These programs should also have periodic monitoring and evaluation to assess learning outcomes. Moreover, these programs should include group sessions to reinforce positive behaviors and mentorship to address the mental blocks WMEs face.

The journey of South Africa’s women-led microenterprises is not just a story of struggle—it is one of resilience, ambition, and transformation. From Zanele’s determined fight to keep her family afloat to Thandiwe’s drive for efficiency and Gugu’s bold expansion into new industries, each entrepreneur embodies the untapped potential waiting to be unleashed.

But potential alone is not enough—these women need bridges. They need financial tools that understand their realities, training that speaks their language, and policies that empower—not exclude. The question is no longer whether we should invest in these women—it is how quickly we can act to ensure that their businesses do more than just survive. They must thrive.

Written by

Jeanne Nganga

Associate, Banking, Financial Services, and Insurance

Priscilla Okutoyi

Manager, Banking, Financial Services, and Insurance

Kim Kariuki

Associate Partner

Shirleen Olalo

Associate, Banking, Financial Services, and Insurance

Leave comments