Galvanizing climate resilience through locally-led adaptation: Lessons from India’s most vulnerable communities

by Graham Wright, Koumudee Thakur, Priyal Advani and Aarjan Dixit

by Graham Wright, Koumudee Thakur, Priyal Advani and Aarjan Dixit Apr 23, 2025

Apr 23, 2025 6 min

6 min

India’s tribal communities face escalating climate challenges, threatening their livelihoods and cultural heritage. MSC’s Locally Led Adaptation (LLA) toolkit empowers these communities to assess risks, prioritize actions, and develop inclusive adaptation plans rooted in local knowledge. Read the blog to learn more.

In the remote hills of Odisha, India, Meena Juang surveys her drying crops. “We already face water shortages throughout the year,” she explains. “Low rainfall only makes the situation worse.” Across India, particularly vulnerable tribal groups (PVTGs) find themselves on the frontlines of climate change with limited resources to adapt. Over 3.3 billion people live in areas of high climate vulnerability, and indigenous and marginalized communities bear the heaviest burden.

Locally-led Adaptation (LLA) offers a paradigm shift. Unlike top-down interventions, LLA empowers communities to design solutions rooted in their lived experiences and local knowledge. As one Sahariya tribe elder noted, “We know the land’s pain—we’ve seen the rains vanish and the crops wilt. Yet no one asks us how to fix it.” MSC’s LLA community-level toolkit bridges this gap to transform communities from beneficiaries to architects of resilience.

Overview of MSC’s LLA toolkit

The LLA community-level toolkit embodies the eight principles for locally led adaptation endorsed at the 2021 Climate Adaptation Summit. It provides a participatory framework designed to help communities assess hazards and risks, prioritize actions, and develop adaptation plans. The toolkit can be used in diverse ecosystems. MSC has used it from the drought-prone plains of Rajasthan to the flood-affected forests of Jharkhand. It is designed explicitly to be inclusive and give voice to communities through visual mapping, games, and structured discussions.

The toolkit in action

Preparation is key to the toolkit’s effective implementation. Extensive secondary research is vital to understand the nature of climate risks and past activities in the locality. This requires a deeper look at three areas.

- Current climate hazards and impacts and those expected under different representative concentration pathways (RCPs) and, where available, shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs). This knowledge will be imperative to inform the respondents about future climate scenarios.

- Ongoing national and local government, and where appropriate private sector, planning and responses to climate change, including policies and regulatory provisions. These are vital to inform respondents about adaptation options that can lead to a positive impact.

- The availability of formal and informal financial services in the area. This is key to assessing options to fund and implement adaptation plans developed using the toolkit.

Extensive knowledge of these three areas will enable moderators to guide the participants effectively as they use the toolkit to develop their adaptation plans. The toolkit itself comprises six sequential tools designed to be implemented through participatory workshops with diverse community members:

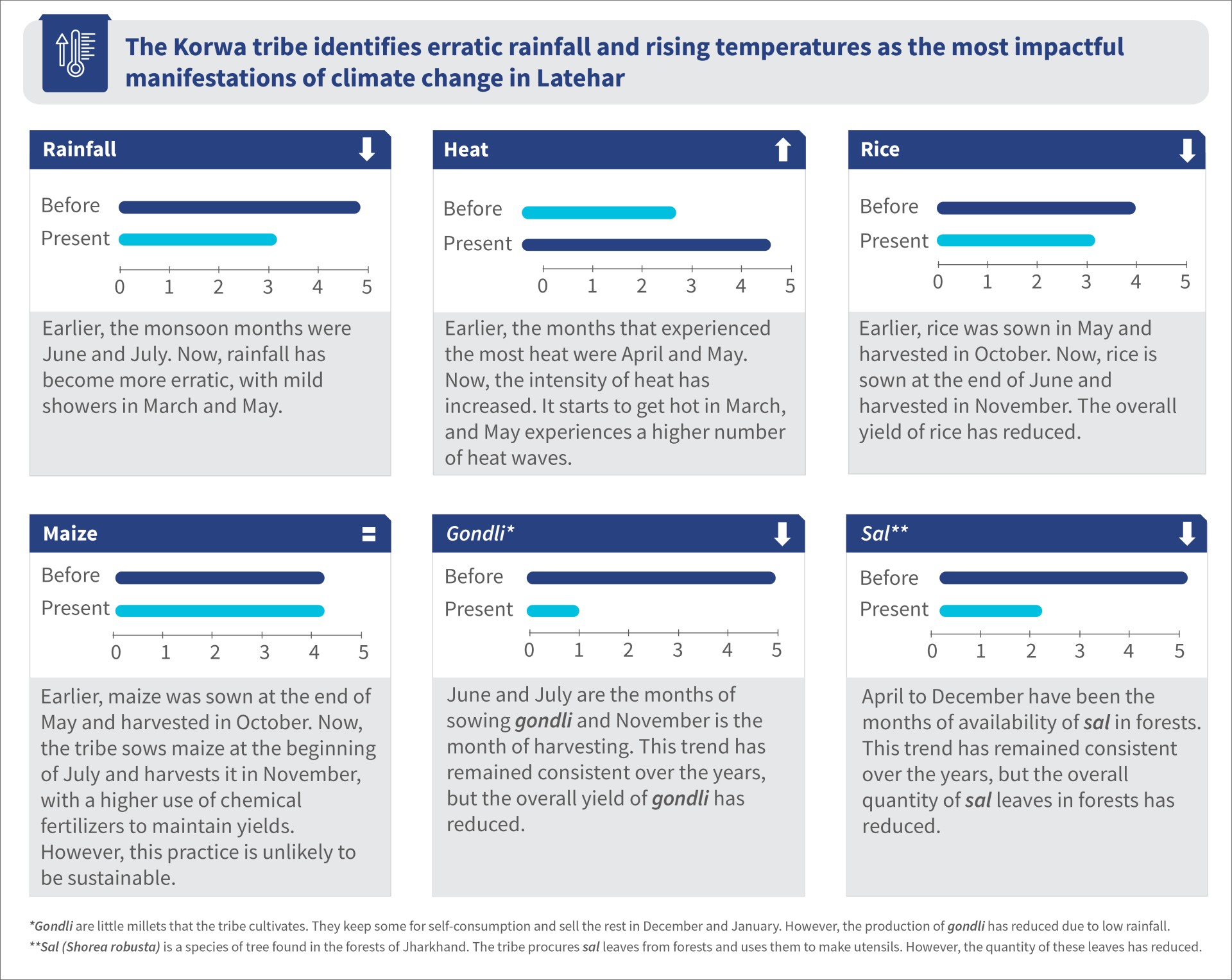

1) Mapping of climate hazards and exposure: Communities use this tool to create visual maps of their area to identify climate-hazard-prone zones and track how hazard patterns have changed over time. The Korwa tribe in Jharkhand, for instance, mapped how monsoon rainfall has decreased while temperature extremes have intensified, affecting crop cycles and forest productivity.

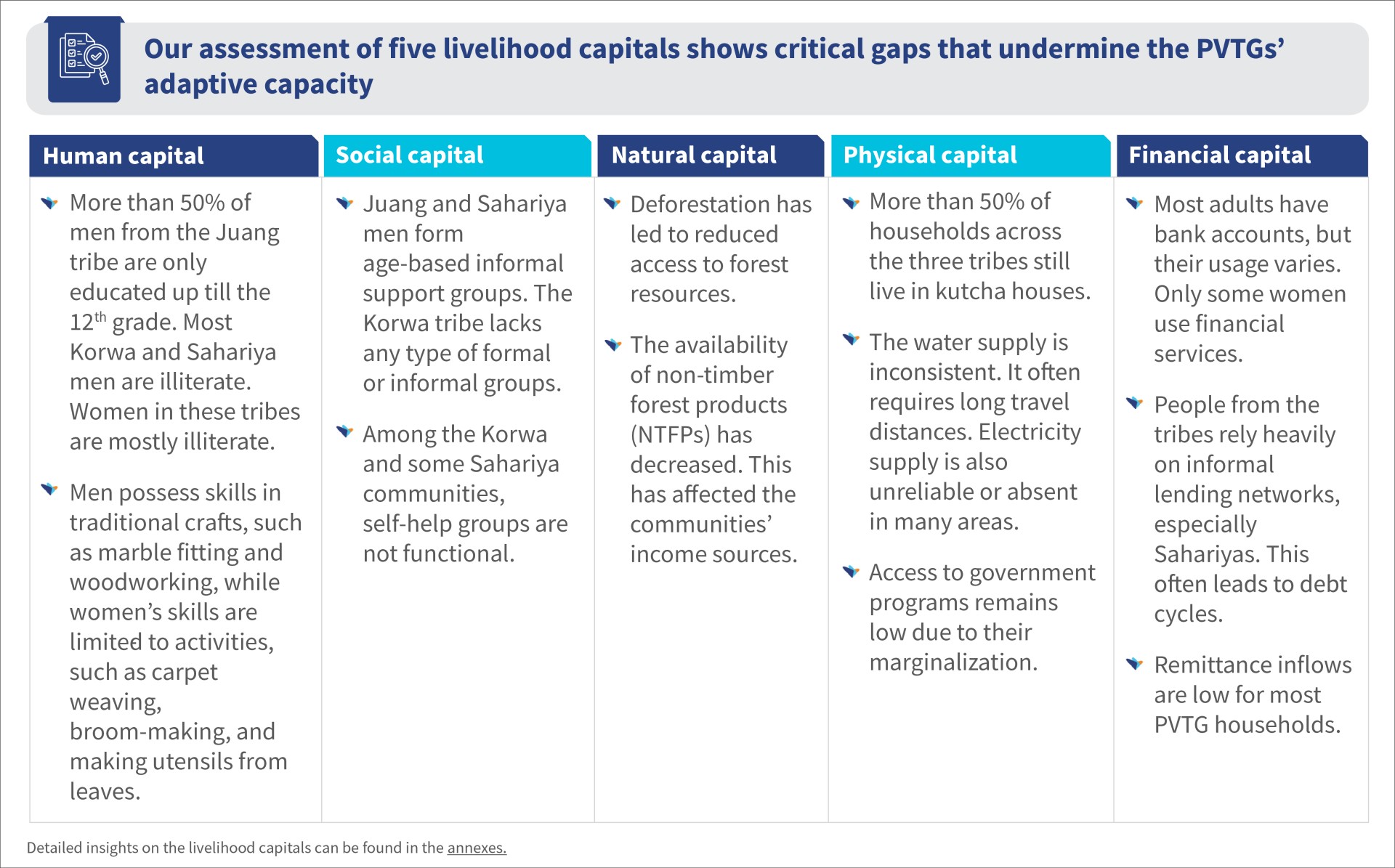

2) Assessment of vulnerability: Using DFID’s Sustainable Livelihoods Framework communities evaluate their five capitals (human, social, natural, physical, and financial) to identify strengths and weaknesses in their adaptive capacity. This reveals critical shortfalls—such as the Korwa tribe’s limited financial capital and the Sahariya tribe’s deteriorating natural resources—while highlighting assets that can be mobilized.

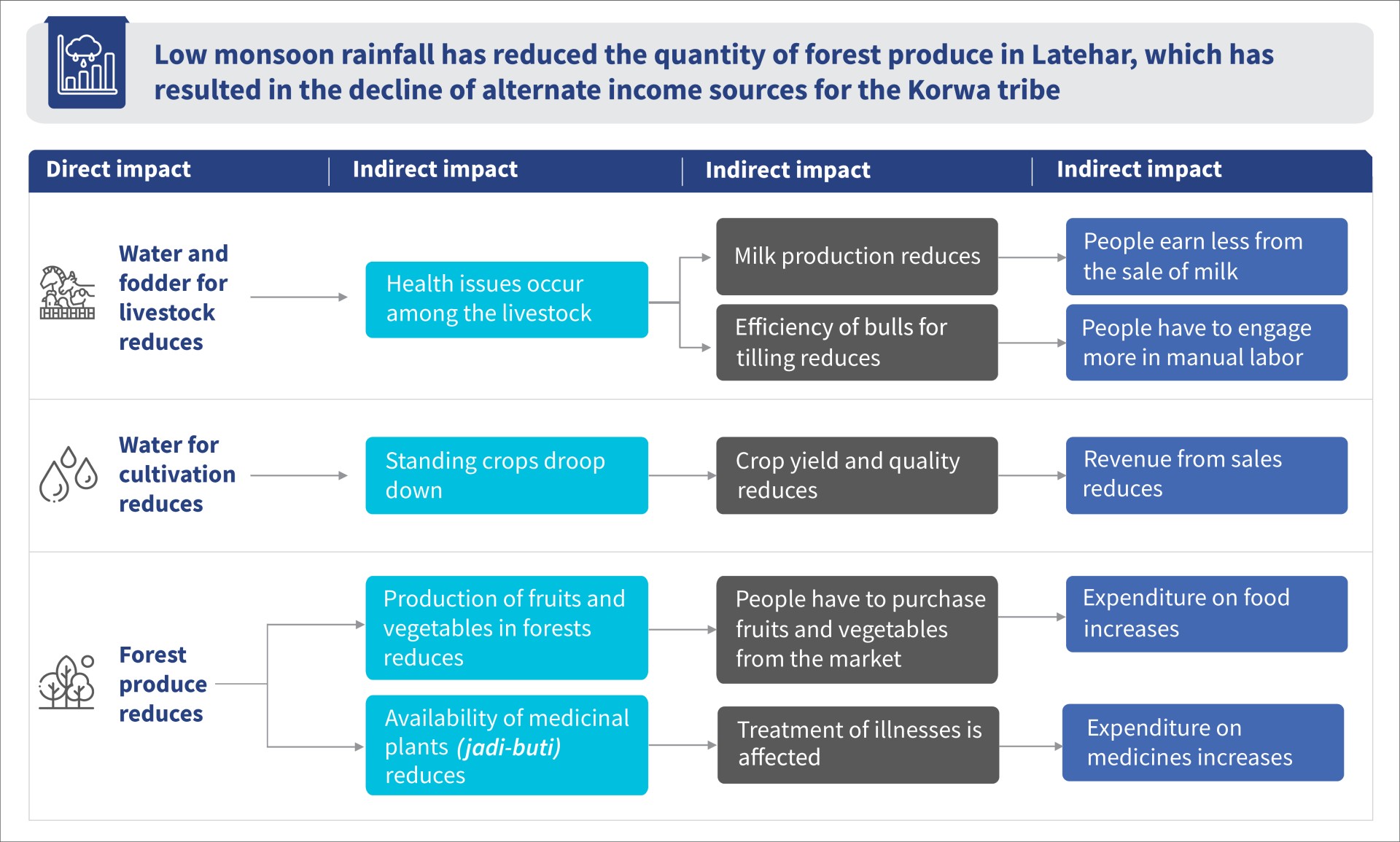

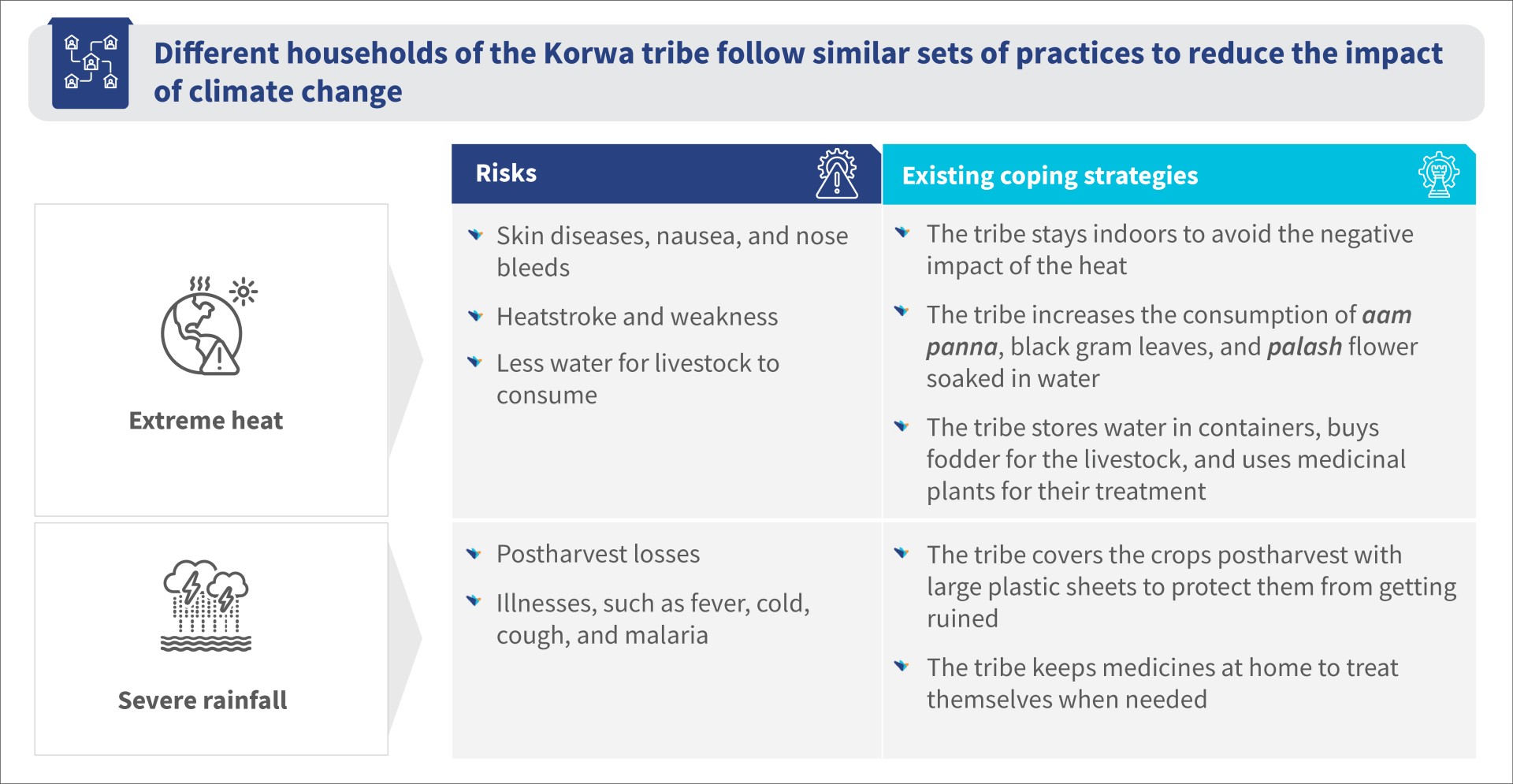

3) Identification of climate-related risks: Participants then analyze how climate hazards interact with vulnerabilities to create direct and indirect impacts. For example, the Korwa tribe mapped how extended dry spells reduce water availability, livestock health, and crop and forest yields, which compounds challenges and compromises household finances.

4) Developing adaptation options: Using innovative methods like modified “snakes and ladders” games, communities brainstorm potential adaptation strategies. This gamification helps participants visualize risks (snakes) and solutions (ladders) in an engaging, accessible format, regardless of literacy levels. Korwa tribe members identified various adaptation options that spanned road and house construction, improved water management systems, and agricultural extension.

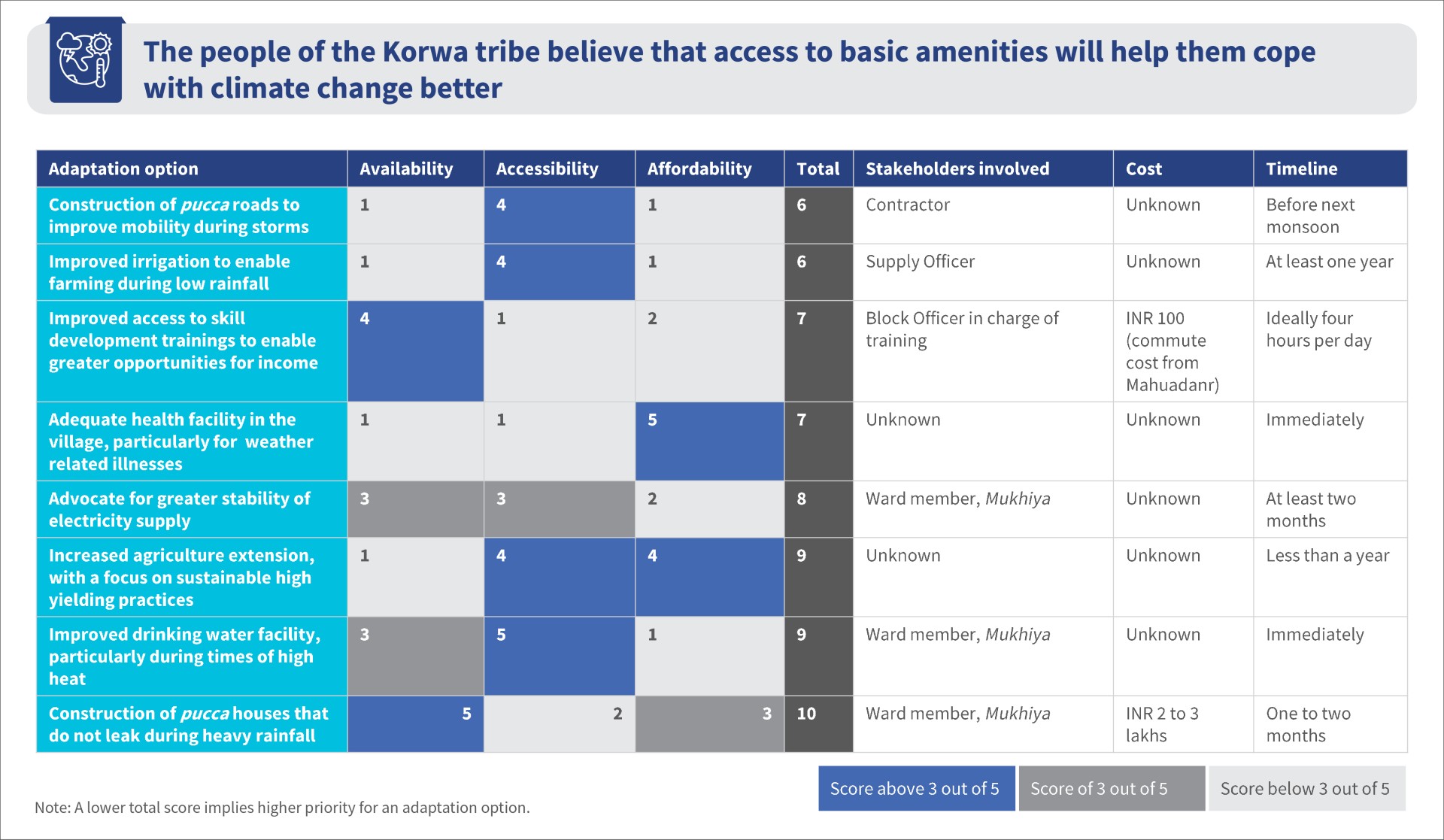

5) Prioritizing adaptation strategies: Communities evaluate potential adaptation options based on availability (is it technically feasible?), accessibility (can we implement it?), and affordability (can we sustain it?). This ensures that final plans reflect realistic, context-appropriate solutions rather than wishful thinking. The Korwa tribe prioritized the construction of pucca houses that do not leak during heavy rainfall and improved drinking water facilities for agricultural and personal consumption during the increasingly hot dry season.

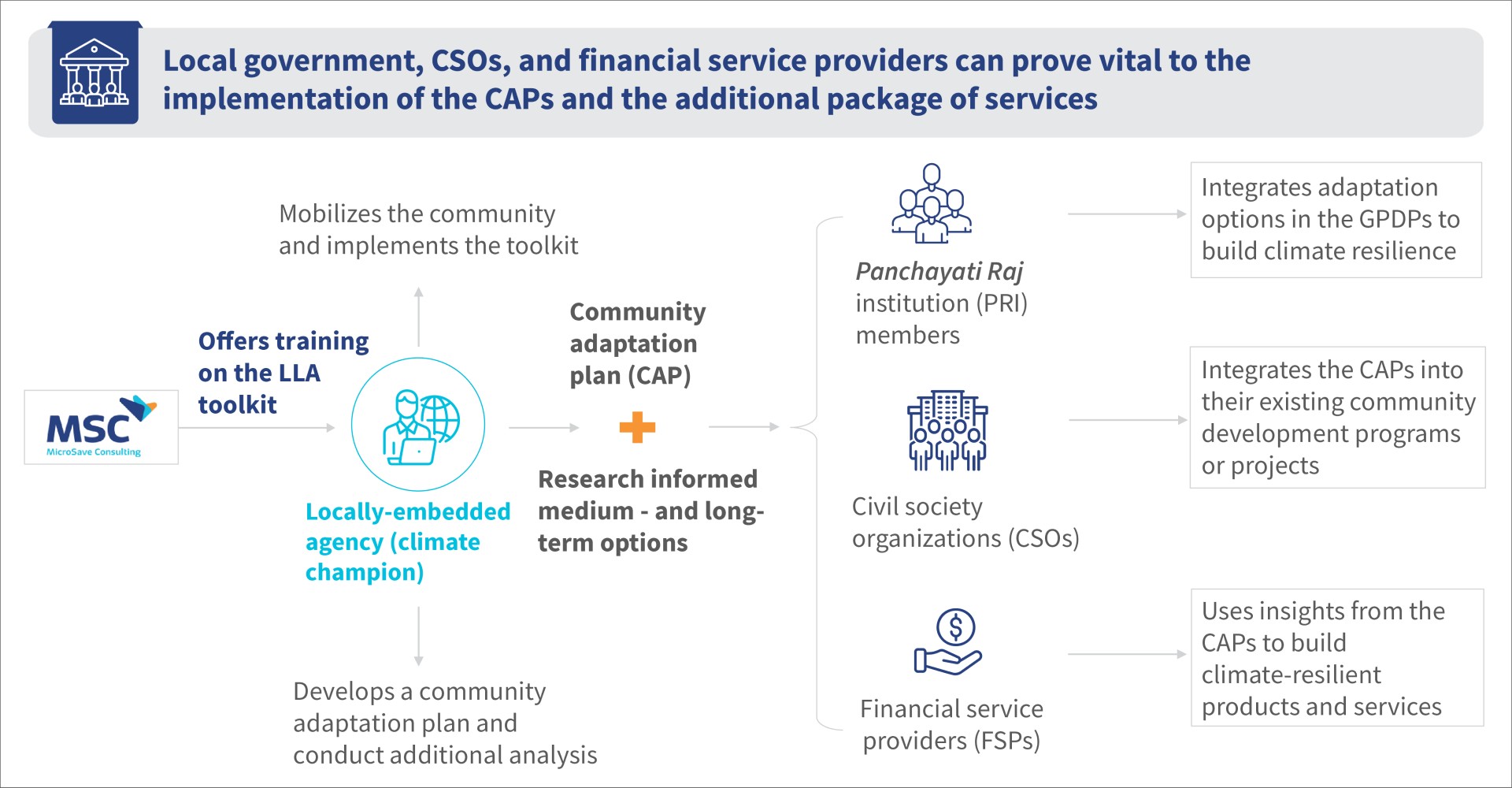

6) Creating a community adaptation plan (CAP): The process culminates in a detailed action plan that specifies activities, milestones, timelines, costs, funding sources, and responsible stakeholders. The CAP brings together different discussion threads that emerged from the deliberations and transforms them into a concrete roadmap for implementation.

Benefits of MSC’s LLA toolkit

The LLA toolkit offers several distinct advantages for those seeking to enhance climate resilience among vulnerable communities:

- Indigenous knowledge meets scientific understanding: The toolkit enables the combination of traditional knowledge with accessible explanations of climate change science. This is essential for the development of technically sound adaptation strategies that are culturally suitable in the context of locally embedded models.

- Complex climate planning becomes accessible: Climate change adaptation involves complex environmental, social, and economic interactions. The toolkit’s approach breaks this complexity into manageable components to enable people to participate meaningfully regardless of their technical expertise or formal education levels.

- Builds communities’ capabilities: The implementation process enables and encourages participants to think through the implications of the unfolding climate crisis and how they can respond to it.

- Adaptability across contexts: The toolkit’s principles can be applied across diverse geographic and cultural contexts. We are already applying them in Bangladesh, Uganda, India, and Indonesia in MSC’s new LLA for MSMEs toolkit. This toolkit’s participatory, game-based approaches and visual mapping techniques transcend literacy barriers and can easily be adapted to local conditions.

- Community ownership drives sustainability: When communities lead the identification of adaptation options, they develop greater commitment to implementation and maintenance. This starkly contrasts with externally imposed solutions that often fail once project funding ends. As demonstrated by the Juang tribe’s enthusiasm for the check dams they helped design, locally-led initiatives create stronger buy-in.

- Integration with existing governance systems: The toolkit complements rather than competes with formal planning mechanisms. In India, community adaptation plans can be integrated into Gram Panchayat Development Plans (GPDPs) to create formal resource allocation and implementation pathways. This integration enhances the legitimacy and sustainability of adaptation initiatives. MSC is now preparing to work with IDH and the local government of Madhya Pradesh to this end.

- Actionable plans attract multi-stakeholder support: Effective coordination among the four key stakeholders is essential for an impactful community-based LLA initiative. Communities develop and own their adaptation plans alongside local government agencies, which ideally would integrate elements of these plans into their formal development agendas. Civil society organizations (CSOs) provide technical support and capacity building to the community, while financial institutions offer suitable financial services. Through the creation of specific, time-bound plans with clear responsibilities, communities can engage government agencies, CSOs, and financial institutions more effectively.

The detailed implementation pathways in the CAP create accountability mechanisms and reduce coordination challenges. They also ensure that community priorities receive adequate resources, technical support, and institutional backing to transform plans into sustainable action.

The path ahead

For practitioners who work with climate-vulnerable communities worldwide, the MSC’s LLA toolkit offers a proven methodology to transform abstract climate concerns into concrete, community-owned action plans. These plans help governments and private sector players to identify ideas more likely to have a positive impact and scale existing climate change adaptation initiatives. They also create avenues for sustainable financing of climate change adaptation initiatives. They encourage partnerships, particularly public-private partnerships (PPPs), to integrate climate adaptation solutions into existing businesses, such as microfinance, agribusiness, healthcare, education, and digital financial services.

Perhaps most importantly, the LLA process empowers communities to move from being passive victims of climate change’s effects to achieving active agency in their lives. As one participant reflected, “Before this process, we only talked about our problems. Now we find solutions together.”

Written by

Graham Wright

Group Managing Director

Koumudee Thakur

Assistant Manager

Priyal Advani

Assistant Manager

Leave comments