How digital tax reforms can transform Nigeria’s revenue challenges into fiscal successes

by Karminder Malhotra, Vikram Sharma, Ritesh Rautela and Diganta Nayak

by Karminder Malhotra, Vikram Sharma, Ritesh Rautela and Diganta Nayak Nov 6, 2025

Nov 6, 2025 6 min

6 min

Nigeria’s limited fiscal space constrains public investment and service delivery. This blog takes a closer look at digital tax reforms driven by data, interoperability, and robust public infrastructure. It further examines how these reforms help transform Nigeria’s revenue system, enhance fiscal resilience, and accelerate progress toward sustainable and inclusive national development.

Nigeria has vast developmental needs which are held back by its equally vast but untapped human, natural, and fiscal potentials. The federal government spends an average of $220 per citizen per year, one of the lowest levels of government expenditure among developing countries. In 2024, Nigeria’s total expenditure was 18.1% of GDP, well below the sub-Saharan Africa average of 22.86%. This underinvestment has direct consequences for its population: a child born in Nigeria today is expected to achieve only 36% of his or her potential productivity due to poor access to quality education and healthcare services.

Low public spending in the country is linked to its constrained revenue base and fragmented system of revenue collection. Adequate revenues allow countries to fund healthcare, education, infrastructure, and social safety nets while maintaining resilience against deficits and global shocks. A narrow fiscal space undermines these goals.

Similarly, although e-governance, including digital public infrastructure (DPI), is becoming a cornerstone of modern public administration, the government faces challenges in digitising public financial management (PFM), particularly at the sub-national level.

Progress in these areas can strengthen revenue mobilisation if leveraged effectively.

The digital opportunity in public financial management

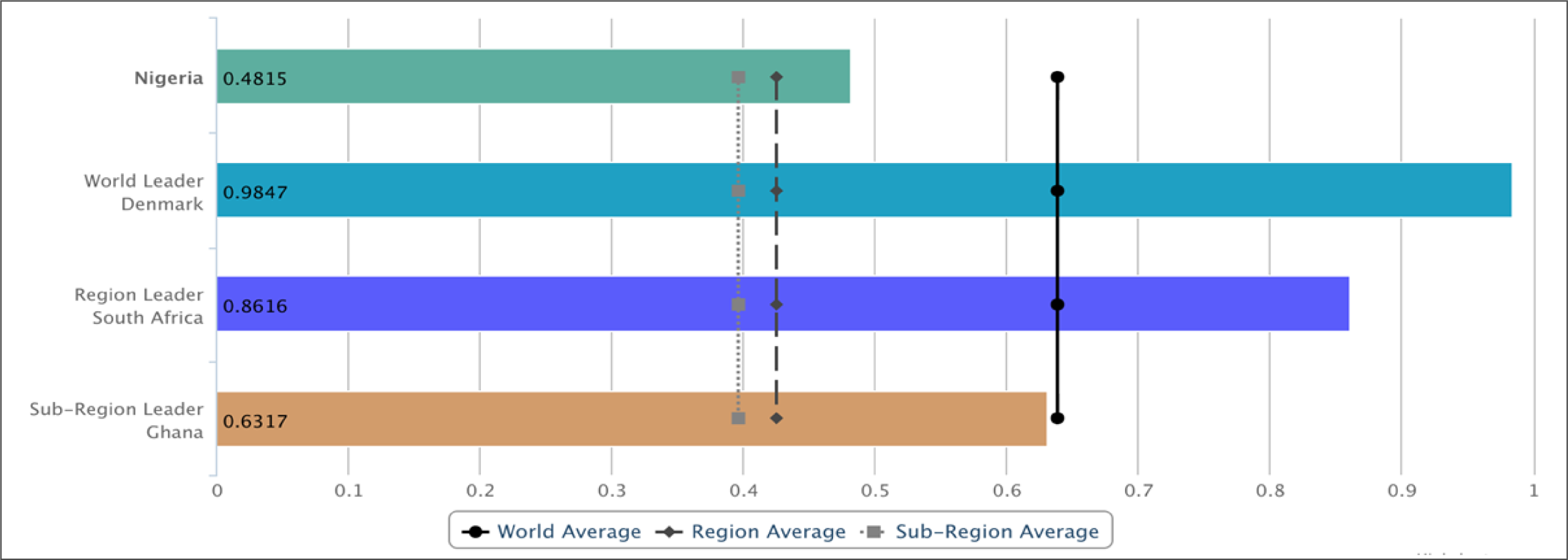

Nigeria has made significant progress in digital public infrastructure, starting with a robust national ID system. As of June 2025, 121 million people out of a total population of 238 million were enrolled in its National Identification Number (NIN) database. This scale of digital ID registration can help expand digital service delivery, where it lags behind peers such as South Africa, Ghana, and Senegal, in the UN e-Government Development Index, including in areas like online service delivery, connectivity, and human capacity, which are conditions that foster revenue mobilisation.

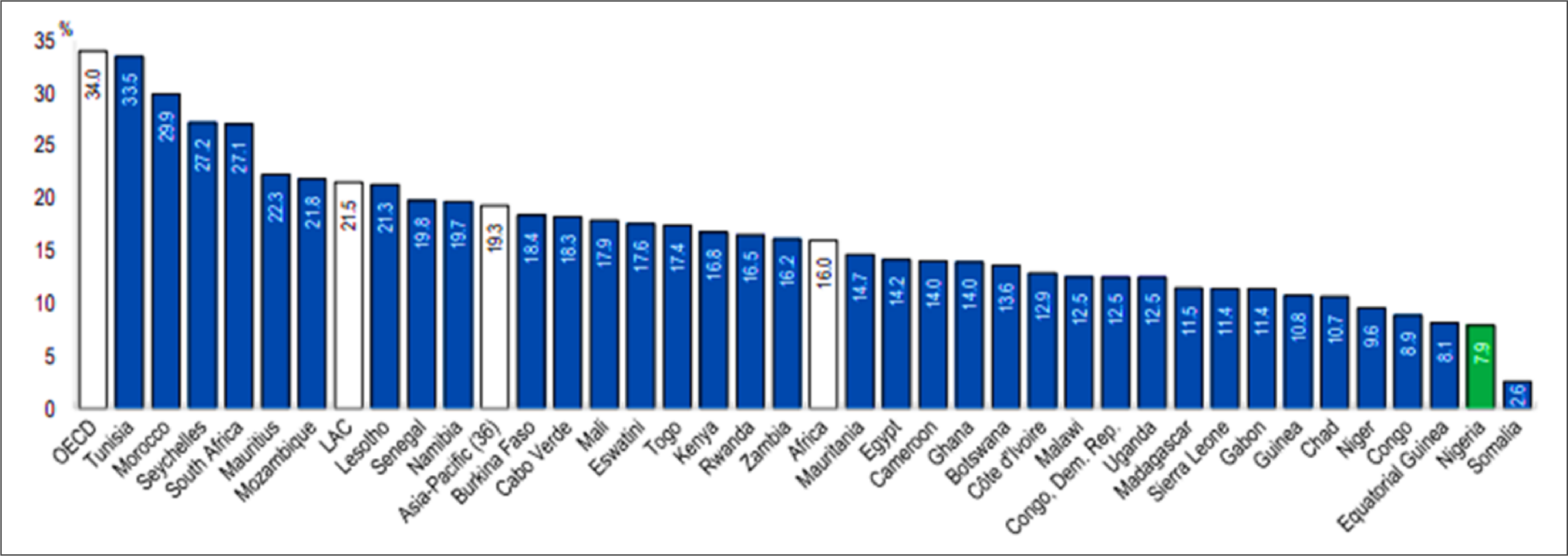

The country’s tax-to-GDP ratio has remained mulishly below 10%, far short of the African average of 16%. By comparison, South Africa’s ratio stands at 26%, Ghana’s at 13%, and Kenya’s at 15%. According to the World Bank, a threshold of 15% or higher is critical for sustaining growth and reducing poverty. This underperformance leaves the government fraught with recurring oversized fiscal deficits. The government’s 2020 National Integrated Infrastructure Master Plan flagged persistent funding gaps in the energy and transport sectors. Low revenues also create macro-fiscal vulnerabilities, such as dependence on foreign exchange and rising public debts. To understand why revenue collection remains so low, it is necessary to examine the country’s direct and indirect taxation systems.

Challenges in direct and indirect taxation

Nigeria’s low tax revenue is beset by underlying impediments in direct taxation, such as low tax morale1, widespread exemptions, and a fragmented tax system. Low trust in government, perceived corruption, multiple overlapping taxes, and poorly coordinated collection agencies all dampen tax compliance. At the same time, generous incentives such as tax holidays, allowances, and exemptions continue to erode the tax base, estimated at USD 4.6 billion (≈4% of GDP) in 2021. Personal income and corporate tax collections are among the lowest in Sub-Saharan Africa at just 6–7% of GDP.

The government has made incremental gains in indirect taxation, particularly through value-added tax (VAT). Centrally collected VAT revenue has grown from 10% to 30% of total revenue despite a relatively low VAT rate of 7.5%, about half the Sub-Saharan African average of 15%. With streamlined rates, VAT could become a dependable revenue source. Yet, without addressing economic, institutional and administrative barriers, such large-scale gains will be far-fetched.

Beyond rates and exemptions, the structure of tax administration itself poses challenges. The fragmented responsibilities of federal and sub-national bodies weaken enforcement. Limited institutional capacity, fragile taxpayer databases, and governance challenges impede progress. The situation is compounded by a large informal economy, which accounts for over 90% of employment, much of which operates outside the tax net. Invariably, a promising revenue mobilisation strategy should be part of a broader development strategy for the country.

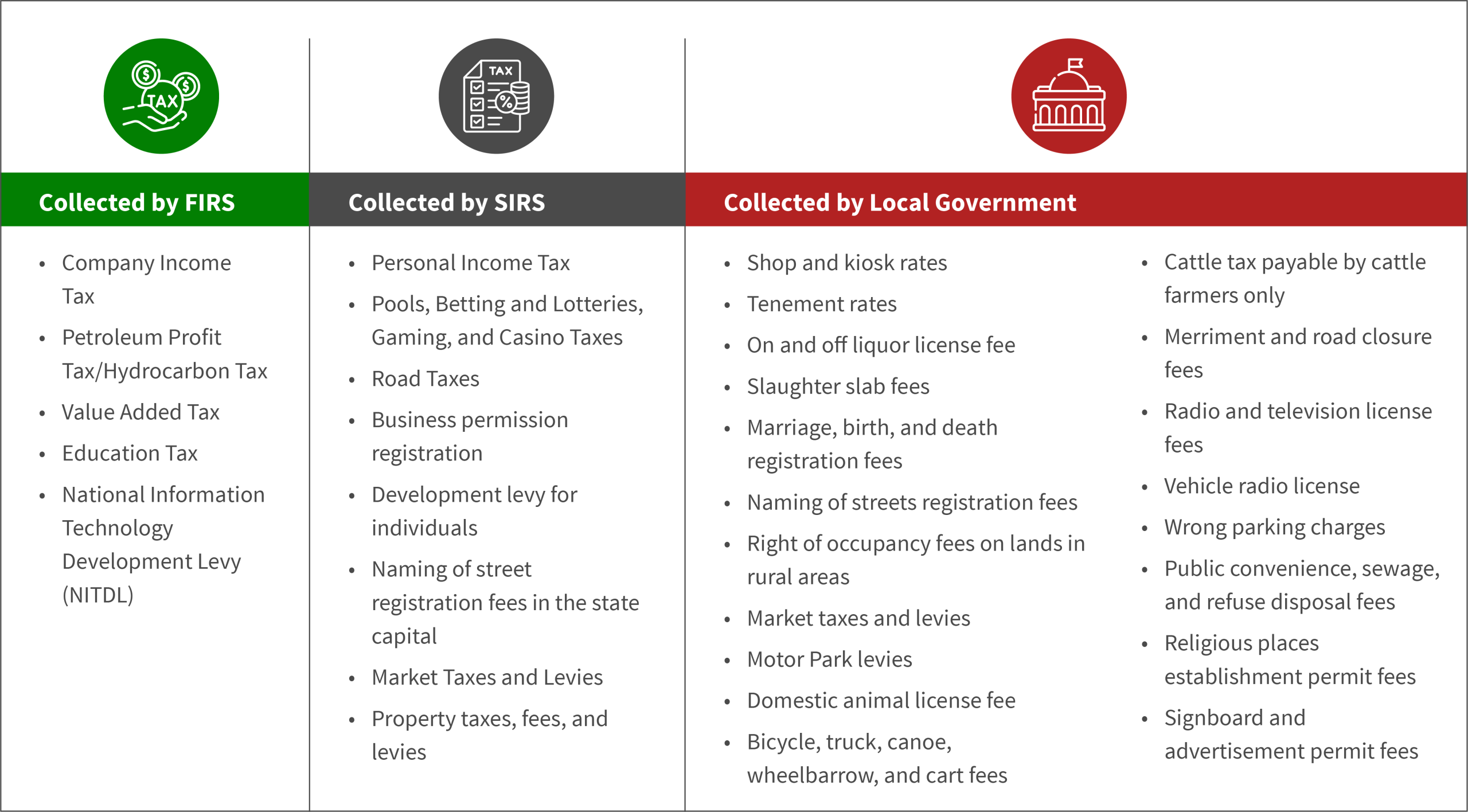

Nigeria’s tax system is structured under a federal framework. Revenue collection responsibilities are divided among the federal, state, and local governments. The Federal Inland Revenue Service (FIRS) administers major national taxes, such as the company income tax and petroleum profit tax, while the Nigeria Customs Service collects customs and excise duties. The State Internal Revenue Services (SIRS) collect taxes such as personal income tax at the state level. These are calculated using the pay-as-you earn (PAYE) method and direct assessment. SIRS also collect capital gains tax for individuals and business premises levies. Local governments collect market fees, tenement rates, and licensing fees for small business operators.

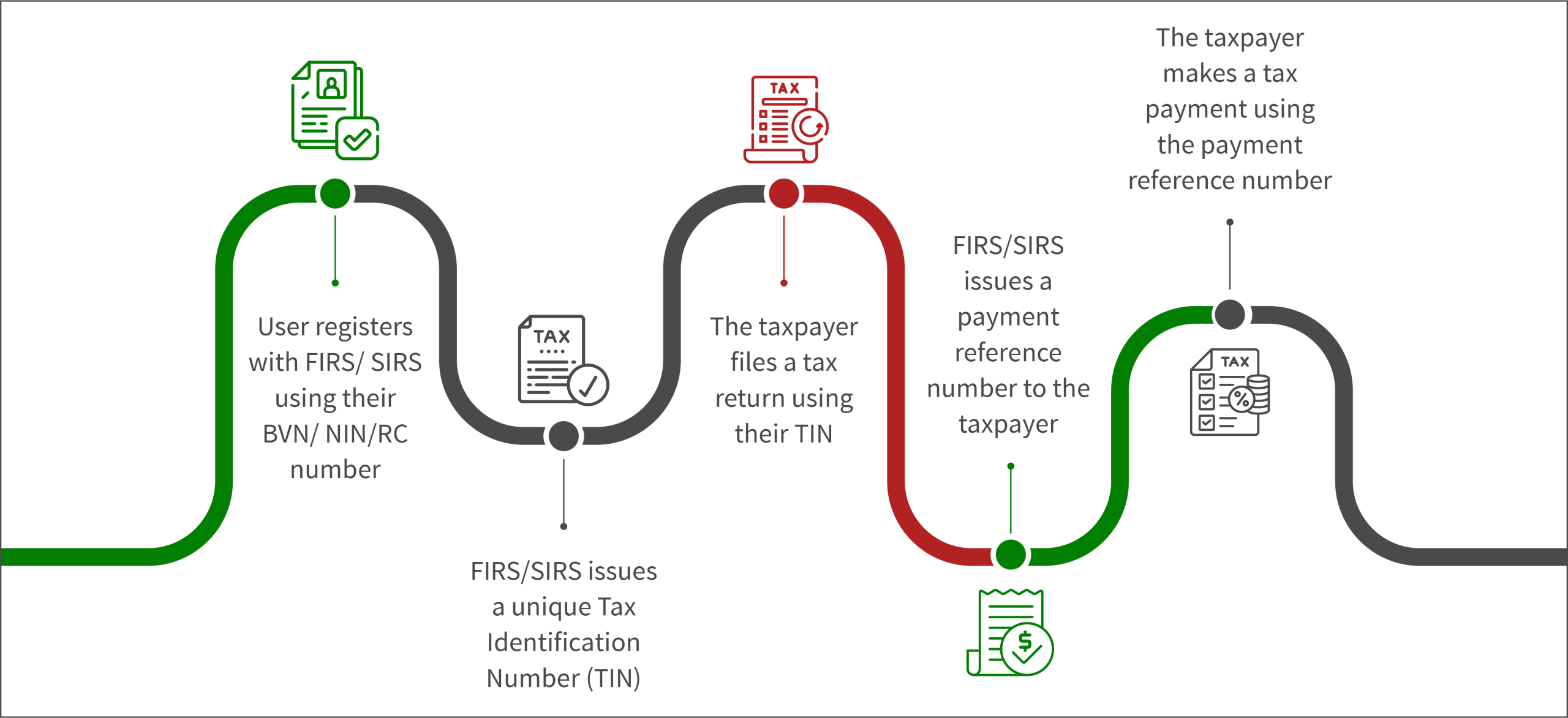

Centrally, the Joint Tax Board (JTB), a cross-government tax body, has collaborated with the FIRS to develop the national taxpayer identification number (TIN) system. However, many tax administration processes, especially at the sub-national level, are still partially digitised. These processes rely heavily on manual and siloed data handling, which undermine accuracy, efficiency, and transparency.

The following are the main challenges in Nigeria’s taxation process:

Fragmented digital systems: Revenue authorities lack a unified, interconnected digital infrastructure. This leads to data silos and fragmented services. Fragmentation prevents seamless information sharing and coordination as authorities expend extra resources to identify taxpayers and enforce compliance.

Manual approval and verification of tax calculation: Manual processes to approve and verify digital IDs and payment receipts, among others, result in delays, errors, and administrative burdens for revenue authorities.

Lack of standardisation and data observability: Tax collection is opaque, and receipts are not standardised. The process involves discretionary assessments or waivers, while online portals or public notice boards are underutilised. This erodes public trust and discourages voluntary compliance.

Varied levels of automation: Revenue authorities have different automation levels, whichcontribute to inconsistent and inaccurate tax collection. These differences lead to poor data management, sharing, and reporting across states.

Non-standardised taxpayer identification number (TIN) generation: Authorities generate and manage TINs inconsistently. This creates duplicate TIN records and limits the accuracy of taxpayer profiles.

Variations in level and type of digital financial inclusion: Low digital financial inclusion limits Nigeria’s revenue potential. Many adults still lack formal financial access, which leads to cash based, informal transactions. This creates haphazard audit trails and complicates effective taxation.

Emerging reform effort to strengthen revenue mobilisation

The Nigerian government has started implementing reforms to strengthen the tax system. The country seeks to boost its tax-to-GDP ratio to 18% by 2026. In July 2023, President Bola Ahmed Tinubu inaugurated a Fiscal Policy and Tax Reform Committee, which has introduced measures to increase the tax-to-GDP ratio, including a set of legislative reforms that will transform the operating environment at both the federal and sub-national levels. The committee also seeks to modernise revenue administration and combat leakages using technology and data intelligence.

On 26 June 2025, four (4) Tax Reform Bills were signed into law by the President, including the Nigeria Tax Act (NTA), the Nigeria Tax Administration Act (NTAA), the Nigeria Revenue Service Act (NRSA) and the Joint Revenue Board Act (JRBA). These changes have been regarded as one of the most comprehensive tax reforms in Nigeria’s history.

The country requires technological advancements, alongside a parallel digital drive at the state level, to achieve the ambitious tax target by 2026. In June 2024, the Nigeria Governors’ Forum (NGF) entered into a partnership with MSC (MicroSave Consulting) under NGF’s Digital Domestic Resource Mobilisation (DDRM) initiative to help states adopt digital public infrastructure (DPI) or DPI-based digital tools as a pathway to digital tax reforms.

The initiative assessed the 36 Nigerian states on their digital maturity, digital PFM ecosystem, and the readiness of their revenue administration systems to adopt digital tax reforms. The assessment was informed by four principles of Digital Public Financial Management: a single source of truth, just-in-time strategy, observability, and de-monopolising access to public resources.

States used an Intelligent Revenue Authority (IRA) index to understand the extent of their revenue systems’ digital readiness. The index is informed by MSC’s in-house smart payments tool, which is designed to reduce friction in payment processing and administrative burden for governments. A complementary Digital Public Infrastructure (DPI) Index was also designed to assess their enabling environment (policy, skills and infrastructure availability), foundational building blocks (digital IDs, payment and data sharing systems), and delivery of public services (service platforms and sector initiatives).

The results provide the first comprehensive analysis of the digital capacity and readiness of the 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory (FCT), their maturity levels (low, medium, or high), and actions to advance and meet their revenue goals.

Customised roadmaps were also developed and distributed to the states through multi-stakeholder dialogues with their IT ministries, revenue authorities and governors. States have been advised to adopt context-specific digital tools that are secure, scalable and interoperable.

This blog was first published on “Nigeria Governor’ Forum” on 4th November 2025.

Written by

Karminder Malhotra

Assistant Manager

Vikram Sharma

Senior Manager

Ritesh Rautela

Associate Partner

Leave comments