Wi-Fi voucher: A top-selling product for rural corner shops in Indonesia

by Rahmatika Febrianti, Yani Parasti Siregar and Raunak Kapoor

by Rahmatika Febrianti, Yani Parasti Siregar and Raunak Kapoor Sep 3, 2021

Sep 3, 2021 6 min

6 min

In Indonesia, 12,548 villages still lack access to 4G internet. This blog explores how Wi-Fi vouchers help diarists under our Corner Shop Diaries project and others in rural Indonesia access the internet.

Corner shop owner Yuyun finds it difficult to connect to the internet on her phone from her village of Gunungpayung in the hilly terrain of Temanggung regency. The village in Central Java lies 458 kilometers east of the capital of Jakarta. Yuyun sells daily necessities from a corner shop in her home. She also runs a coffee roasting business in the village. She is one of our diarists from MSC and L-IFT’s Corner Shop Diaries project. Gunungpayung is not the only rural area in Indonesia that has no or limited internet access.

Corner shop owner Yuyun finds it difficult to connect to the internet on her phone from her village of Gunungpayung in the hilly terrain of Temanggung regency. The village in Central Java lies 458 kilometers east of the capital of Jakarta. Yuyun sells daily necessities from a corner shop in her home. She also runs a coffee roasting business in the village. She is one of our diarists from MSC and L-IFT’s Corner Shop Diaries project. Gunungpayung is not the only rural area in Indonesia that has no or limited internet access.

However, even though she faced difficulties accessing the internet, Yuyun used several methods to sell her products to her clients, who live as far away as Jakarta. These included the use of WhatsApp to advertise her small business, promotional posters that she created on a design app, and Shopee—an e-commerce platform—to sell her products. What is her secret of being technologically savvy and well connected in a place without internet access?Reports indicate that access to 4G networks evades 12,548 villages in the country. While 90% of 4G signals are available in urban areas, the number falls to only 76% in rural areas. In Java, the most developed and populous island in the archipelago, the internet penetration rate is only 56.4%. In less populous islands, such as Sulawesi and Papua, the rate of internet penetration falls to below 10%. This inequality results from various factors, including geographical conditions, a notion among providers that rural and sparsely populated areas are not profitable, and a lack of regulation in infrastructure and frequency-sharing.

Yuyun showed us a box stenciled “Voucher – Wi-Fi” where she kept a pile of paper coupons (the vouchers). The coupons allow buyers to access the internet. She sells two kinds of coupons, one worth IDR 2,000 (~USD 0.14) for two-hour unlimited use and another worth IDR 5,000 (~USD 0.35) for all-day unlimited use. Such coupons are reasonably cheap and cost the same as a small box of milk that children usually buy. The package details are printed on the coupon. Customers only need to turn on the Wi-Fi feature on their mobile phone, enter the username and password, and connect to the internet.

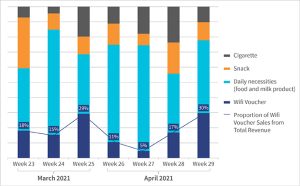

The chart below shows the share of Wi-Fi voucher sales in Yuyun’s weekly revenue compared to other products, for example, snacks and daily necessities. The revenue from Wi-Fi voucher sales varied from time to time, from IDR 8,000 (~USD 0.56) to IDR 185,000 (~USD 12.96) per week. It shows that despite not being the main selling product, the Wi-Fi voucher remained a constant part of Yuyun’s total revenue.

Yuyun is not the only one who sells Wi-Fi vouchers in her area. The Wi-Fi voucher business is mushrooming, especially in densely populated areas with many blank spots in Temanggung and Wonosobo. The business model of Wi-Fi vouchers is through agencies. Small sellers like Yuyun are agents who receive routers and coupon papers from larger entrepreneurs. These entrepreneurs usually understand networks and other technical issues better and also determine the market price of Wi-Fi vouchers. Agents like Yuyun earn around IDR 500 – IDR 1,000 (~USD 0.035 – USD 0.070) from sales per coupon.

The signal of the Wi-Fi network, which Yuyun sells vouchers for comes from an access point device installed in her house. The access point functions as a “repeater” and extends the range of the internet signals that the users could not reach earlier. Yuyun spent IDR 70,000 (~USD 4.89) to install the access point. Meanwhile, the fee charged for personal use is IDR 350,000 (~USD 24.45) for access point installation and IDR 30,000 (~USD 2.10) for internet usage per user per month.

The Wi-Fi signal is sourced from the fiber optic cables owned by big internet providers, such as PT Telekomunikasi Indonesia (IndiHome). The Wi-Fi voucher entrepreneurs usually live close to the location of the fiber optic cables. They subscribe to internet data from an established provider and then they connect their modem to the router using a LAN cable. This router serves as a bandwidth distributor. Some routers also have an implanted access point to transmit the signal to the user, although others have to buy an access point device separately. The router has hotspot software embedded. The device is then connected to the PC using a cable to operate the software. The Wi-Fi voucher entrepreneur then sells the Wi-Fi signal through agents like Yuyun. They install access point devices in the agent’s house or corner shop so the signal can be distributed there. Ideally, Wi-Fi users should be maximum of five meters from the access point device to get optimum signal strength.

The router, access point devices, and other tools needed for this business are not hard to procure. These tools can be purchased easily at local computer stores or through e-commerce platforms. The prices also vary and are dynamic following the fluctuation of the USD exchange rate.

The quality of the Wi-Fi signal is more stable than the ordinary mobile network signal because it comes from an optical cable and is relayed by several extenders constantly. Errors or outages are rare. When they occur, it is usually for three reasons. First, the big providers may experience system disruption, for example, due to extreme weather. Second, the Wi-Fi entrepreneur may not have paid the internet subscription bill to the primary provider. Third, the access point device may be damaged, for example, due to unstable electricity or lightning strikes. Disruptions are rare because the big providers carry out system maintenance routinely and the electricity supply is usually good. However, if services are disrupted, an agent like Yuyun cannot do anything because they depend heavily on the performance of the Wi-Fi entrepreneur and the primary provider.

The Wi-Fi voucher model is not something new. Big mobile providers like Telkomsel have previously sold internet voucher products at affordable prices. The demand for internet packages has increased since 2013, along with the widespread use of Android-based mobile phones. However, the bigger mobile providers’ signal usually comes from a base transceiver station (BTS) tower, which is not as stable as the signal from optical cables. Compared to optical cables, the BTS tower has a broader coverage area. The signal from the BTS tower faces more obstacles or blockaders, such as hills, large trees, and buildings, resulting in blanks spots. The Wi-Fi voucher business carried out by local entrepreneurs who use optical cables covers these gaps.

The Wi-Fi voucher customers are diverse. However, Yuyun observed that the low-priced packages are usually in demand by children and teenagers, while adults usually consume the more expensive packages. The Wi-Fi voucher is used mainly for online gaming, streaming via YouTube and Facebook, and downloading big-sized data. These vouchers have also helped support school-from-home activities, which corresponds with MSC’s study that household internet needs have spiked during the pandemic.

Coming back to Yuyun, we see that despite limited access to resources, Wi-Fi vouchers proved to be an opportunity. The entrepreneur used the internet to develop her business despite limited access to resources. However, information obtained from the internet was not the only inspiration for Yuyun to become technologically savvy. For example, migrant neighbors or relatives visiting from the city also gave Yuyun insights into current events and opportunities for those like her who lived in rural Indonesia.

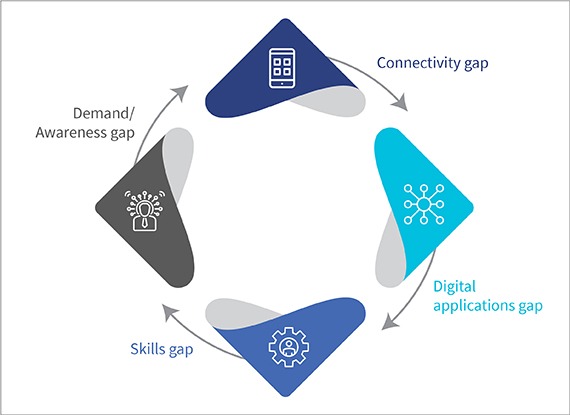

Even though Yuyun is internet literate, she is yet to explore other technological tools and services. For example, she has never tried using digital payments. Her store on the e-commerce platform Shopee is dormant, and she is yet to reactivate it. Yuyun is young and relatively more tech-savvy compared to other micro-entrepreneurs in her village. However, concerted efforts from both public and private sectors are needed to enable digital infrastructure and provide digital skills to micro-enterprises in remote rural areas. These efforts can then speed up the trickle of benefits from Indonesia’s booming digital economy down to the villages like Gunungpayung.

Countries such as India and China now harness the benefits of public investments from building an inclusive digital infrastructure. Yet digital infrastructure alone is not adequate to ensure inclusive digital ecosystems: awareness, skills, and the application of digital tools are required.

Indonesia has set ambitious goals through the BAKTI program, UKM Naik Kelas, and Payments Vision 2025 to ensure that country is well prepared to build an inclusive digital economy. While such programs encourage the private sector to provide digital services to the last mile, they must also use rural community networks to ensure effective delivery and enhanced adoption of their program and initiatives. Involving and empowering rural entrepreneurs like Yuyun is crucial.

Leave comments