How locally-led adaptation can make the inherent resilience of MSMEs in Uganda’s cattle corridor bankable

by Mandira Sharma, James Onyutta, Graham Wright and Pranav Singh

by Mandira Sharma, James Onyutta, Graham Wright and Pranav Singh Oct 31, 2025

Oct 31, 2025 7 min

7 min

Uganda’s MSMEs and farmers face worsening drought impacts that disrupt livelihoods and credit systems. MSC’s LLA-IFSP Toolkit, piloted with FINCA Uganda, helps lenders identify climate risks, tailor financial products, and integrate adaptation into sustainable lending strategies.

Godfrey is not alone. Uganda’s MSMEs and farmers form the but struggle with the growing impacts of climate change. Droughts are now more frequent and prolonged, which disrupts rain-fed farming and pastoral systems. The 2010–2011 drought alone led to losses worth USD 1.2 billion, which is approximately 7.5% of Uganda’s GDP. In the cattle corridor districts of Nakasongola and Masindi, drought consistently ranks as the most severe hazard, as it dries up water points and destroys pastures. Recurrent drought also causes slow-onset impacts, such as land degradation and desertification, which strip pastures, exhaust soils, and depress future productivity.

Godfrey is not alone. Uganda’s MSMEs and farmers form the but struggle with the growing impacts of climate change. Droughts are now more frequent and prolonged, which disrupts rain-fed farming and pastoral systems. The 2010–2011 drought alone led to losses worth USD 1.2 billion, which is approximately 7.5% of Uganda’s GDP. In the cattle corridor districts of Nakasongola and Masindi, drought consistently ranks as the most severe hazard, as it dries up water points and destroys pastures. Recurrent drought also causes slow-onset impacts, such as land degradation and desertification, which strip pastures, exhaust soils, and depress future productivity.

For lenders, these shocks drive arrears, delay repayments, and distort credit demand. The default strategy in such conditions is to withdraw from the market. However, they reveal a pathway for innovation, which includes adaptation efforts to generate finance opportunities if lenders can design products aligned with seasonal shocks and recovery periods.

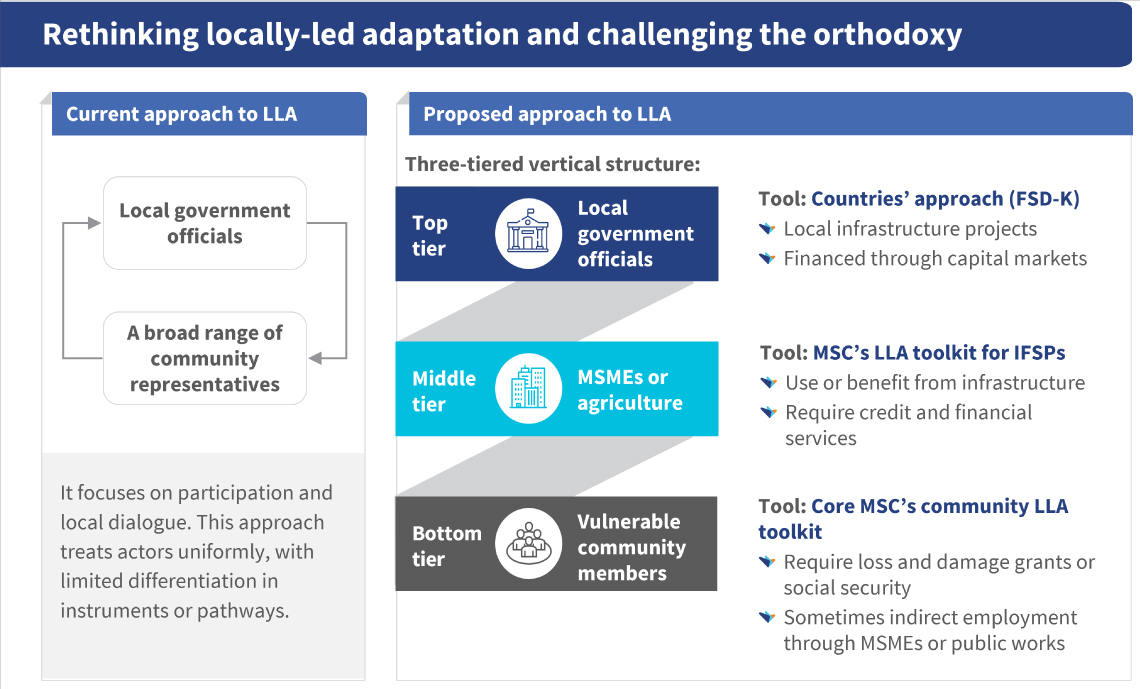

This is where locally-led adaptation measures become crucial. Part one of this series showed how community-level LLA tools help households map hazards and cocreate adaptation options. This second part shifts the focus to the middle tier of MSMEs and their lenders. MSMEs are often banked and have cash flows with repayment capacity, which allow lenders to underwrite adaptation investments. They anchor value chains and provide crucial market services, yet remain climate-exposed.

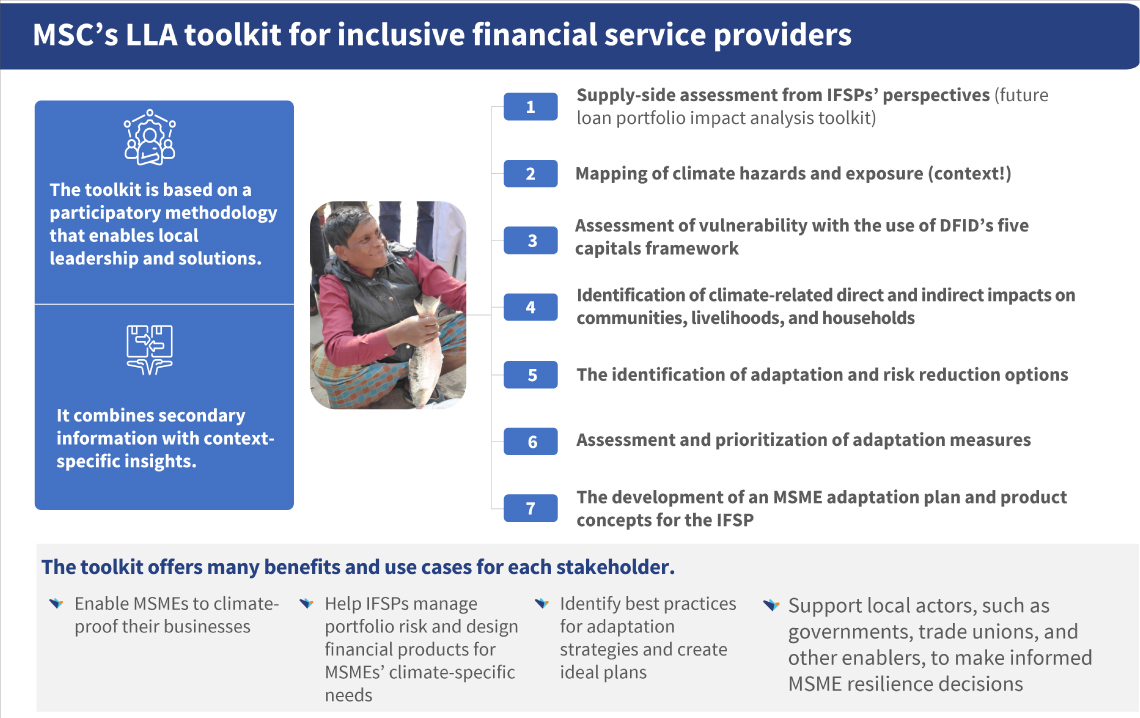

MSC’s LLA toolkit for IFSPs (LLA-IFSP toolkit) is built for this tier. It enables lenders to trace climate impact pathways across household journeys, from hazards and vulnerabilities to impacts on livelihoods and supply chains that include inputs and outputs. Lenders can adjust product structures and translate MSME insights into phased, financeable plans.

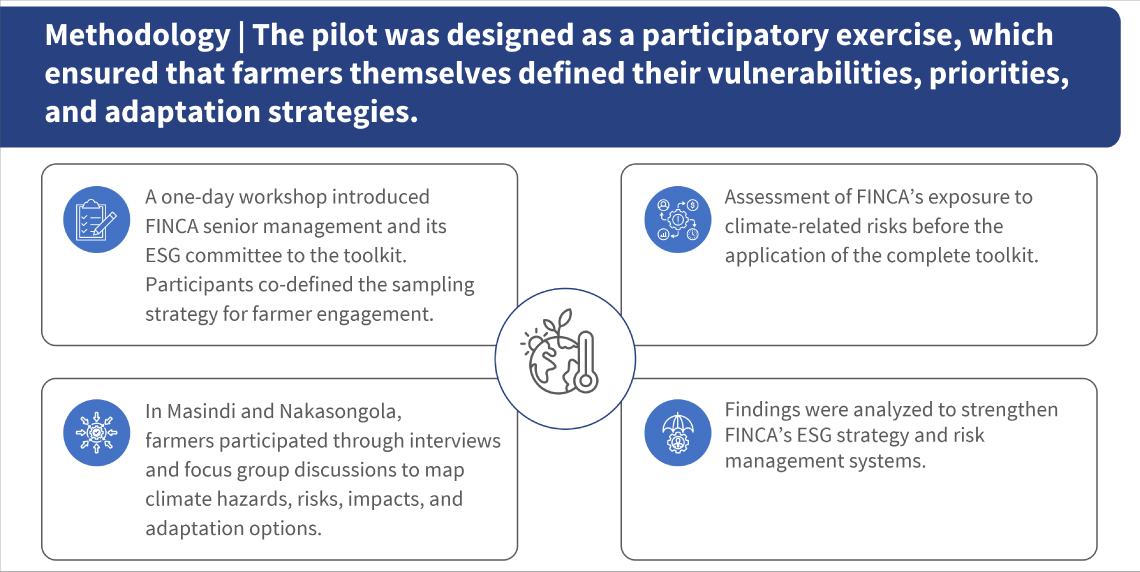

Against this backdrop, MSC partnered with FINCA Uganda to pilot its LLA-IFSP Toolkit. The exercise exposed material climate risks in FINCA’s portfolio, which clarified client adaptation needs, and generated product concepts that aligned with seasonal cash flows. It highlighted climate change as a risk to manage and an opportunity to expand the customer base. This approach could improve portfolio quality, de-risk existing lending, and place climate risk at the core of the ESG strategy.

Preparation is the key

Before the application of the toolkit, secondary research is vital to understand the nature of climate risks and past activities in the locality. This requires a deeper examination of the current climate hazards and impacts, which are expected under different representative concentration pathways (RCPs) and shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs). This knowledge will be essential for the discussion of future climate scenarios with participants in the field-based exercises.

Insights from the toolkit

Tool 1: Supply-side risk analysis

The tool highlighted how drought stresses FINCA’s loan book. The findings were stark, as approximately 25% of FINCA’s clients are in climate-sensitive sectors. During droughts, these borrowers consistently missed one to two installments per cycle. This pattern increased PAR≥30 by 0.5–1%, with projections that suggest it could double to 1–2% within three years.

The data revealed that recovery is possible. Post-event loan cohorts appeared significantly cleaner, which shows that the problem is not weak underwriting or poor repayment culture, but the strain the households faced during droughts. Grace periods and moratoriums can give clients the time they need to recover.

Subsequent tools (2-7) that were implemented in the field comprised:

Tool 2: Mapping climate hazards

Participants use this tool to identify climate-hazard-prone zones and track changes in hazard patterns. Here, farmers rated drought severity as “five out of five.” They reported longer dry seasons. The farmers explained how enclosures and new veterinary rules hindered coping strategies, such as relocation of cattle to lakes.

Tool 3: Vulnerability assessment

This tool used the DFID’s sustainable livelihoods framework to map resilience across five capitals, which reveals the fragility of rural households when droughts strike.

- Natural capital erodes as water sources dry up, pasturelands degrade, and elevated temperatures reduce crop and livestock productivity.

- Physical capital has also degraded. Kraals, the wooden enclosures that protect cattle, collapse under drought stress and termite damage, which causes livestock to escape. This results in fines for encroachment on private land.

- Financial capital is razor-thin. Most farmers work with little savings and limited access to credit, which hinders recovery after a single failed season. VSLAs and informal lenders are unable to support large-scale investments in adaptation.

- Social capital remains essential, but it has limits. Neighbors share small amounts of fodder or drugs with each other. Yet, such help is limited in scale and cannot sustain households through prolonged and widespread shocks.

- Human capital is under immense stress. Drought dries up fields, water sources, and pastures. Hired laborers and men often migrate in search of work, which leaves women and children to shoulder additional burdens.

Tool 4: Climate-related impacts

Participants analyze how climate hazards interact with vulnerabilities to create direct and indirect impacts. They trace impacts through value chains, which reveals the ripple effect. Direct impacts include crop failures, storage losses, livestock stunting, and livestock mortality. Meanwhile, indirect impacts include lost contracts, inflated input prices, reduced access to formal and informal credit, and reputational damage.

Tool 5: Adaptation options currently

This tool looks at how MSMEs have already adapted to climate stress and whether those strategies are sustainable. It helps distinguish between temporary coping mechanisms that merely keep businesses afloat versus genuine adaptation that builds their long-term resilience. An assessment of coping strategies revealed that farmers sought short-term fixes. The farmers adjusted feed times and shifted meals to cooler hours of the day so animals could withstand heat stress. They purchased additional grass, often at high cost, to replace depleted pasture. They also hand-carried water to livestock, a labor-intensive task to compensate for dried-up sources. These measures kept animals alive in the immediate term but placed heavy burdens on household labor and savings.

Tool 6: Prioritization

Participants brainstorm and evaluate potential adaptation options based on availability (is it technically feasible?), accessibility (can we implement it?), and affordability (can we sustain it?). This ensures that final plans reflect realistic, context-appropriate solutions rather than wishful thinking.

In practice, the prioritization exercise revealed a sharp divide. Farmers consistently ranked long-term investments, such as boreholes, feed stores, and fencing, as suitable measures to tackle droughts. Yet, they also considered these options the least feasible, as finance was out of reach.

The MSMEs are not short on ideas, discipline, or clarity. These enterprises know what works and can develop detailed, budgeted roadmaps for adaptation. Yet, well-designed plans fail to take off without suitably designed financial products and models or incentives that can make these adaptation assets bankable.

Tool 7: Farmer’s adaptation plans

The process culminates in a detailed action plan that specifies activities, milestones, timelines, costs, funding sources, and responsible stakeholders. Farmers presented strong and implementable plans, which include boreholes to secure water, feed stores to stabilize nutrition, and fencing to protect cattle, among others. These plans also included suppliers, installation details, and seasonal repayment calendars that match cash flows. Despite strong business cases, no plans were accepted due to credit ceilings or perceived risk.

The path forward

The pilot highlights the urgent need for inclusive financial service providers to adapt their products and processes to meet the resilience needs of farmers.

- Redesign loan products

- Introduce seasonal repayment schedules aligned with harvest or livestock fattening cycles

- Develop phased lending that supports long-term investments in manageable tranches

- Recognize adaptation as bankable

- Treat investments such as boreholes, feed reserves, and veterinary certification as productive assets

- Bundle credit with adaptation services such as insurance, agronomic advice, and input supplier linkages

- Manage portfolio risks

- Mainstream climate risk into credit assessments and provisioning

- Use early warning systems and local data to predict repayment challenges

- Partnerships and funding

- Mobilize concessional finance, guarantees, and parametric insurance to de-risk adaptation lending

- Partner with development agencies, insurers, and technical experts to support farmers with credit.

A path from risk to resilience

MSMEs are at risk when labeled as “climate risky” without changes in how finance is delivered. This approach could cut MSMEs off from credit entirely when they need it most. In such cases, climate finance that focuses on risk recognition without product redesign leads to exclusion, rather than resilience.

The LLA toolkit helps avoid this trap. It shows lenders how to lend differently and not less. Lenders can align repayment terms with seasonal hazards. They treat adaptation assets, such as boreholes and feed stores, as bankable, and phase credit to manage exposure. Consistent with this toolkit, FINCA Uganda is committed to equip its customers with practical, user-friendly tools and resources to adopt a customer-centric approach in product design and delivery.

This change in approach acknowledges that farmers are not passive victims of climate change but active participants who plan, invest, and adapt. However, what these farmers lack is financial support. As a result, financial institutions can protect their portfolios. This approach enables MSMEs to adapt and demonstrate that climate resilience is not only necessary but also financially viable.

For Godfrey, this means he can have a borehole that keeps his herd alive. For FINCA, it means arrears that stabilize and a portfolio that holds. For both, it means resilience in the face of harsher seasons.

Leave comments