Unlocking financial resilience: How MFIs can solve the climate disaster in Bangladesh’s farm economy

by Shahrukh Ahmed Latif and Samveet Sahoo

by Shahrukh Ahmed Latif and Samveet Sahoo Aug 27, 2025

Aug 27, 2025 5 min

5 min

Around 60 million smallholder farmers in Bangladesh face worsening climate shocks, risking poverty and debt. MSC research shows MFIs can bridge gaps by embedding affordable, trusted microinsurance with credit and savings—offering farmers resilience and insurers sustainable rural reach.

Around 60 million smallholder farmers produce nearly 60% of Bangladesh’s food. However, most lack adequate tools to adapt to the dangerous risks climate change brings. Every year, these farmers face threats, such as floods, droughts, cyclones, salinity intrusion, river erosion, and pest outbreaks. The scale and frequency of these disasters continue to grow, with deadly results.

In 2024, monsoon floods destroyed 1.1 million metric tons of rice, while Cyclone Remal damaged crops across 50 districts, and a record-breaking April heatwave scorched rice and fruit harvests. In coastal Khulna, salinity intrusion and drought wiped out more than 18,800 hectares of paddy and vegetables. In November 2023, Cyclone Midhili flooded farmlands and affected more than 160,000 farmers. For families who already live on the edge, one bad season can push them back into poverty. This forces them to make painful trade-offs between food, education, and healthcare.

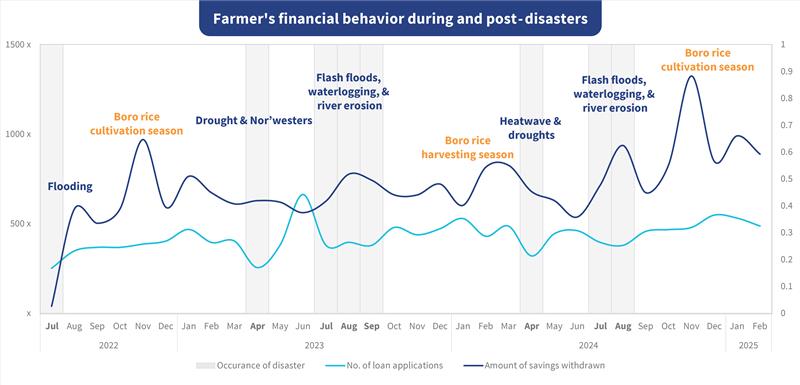

MSC recently conducted a study on agri-allied customers in some of Bangladesh’s most climate-vulnerable regions. We found that when a climate shock hits, farmers react with urgency. They withdraw any savings or sell off assets to buy food, repair homes, replace lost livestock, and cover other important expenses. The need for capital surges once the immediate crisis has passed, as farmers must replant crops, rebuild structures, and replace equipment. This drives up the demand for loans. However, they hesitate to take on new debt as income sources become uncertain. MSC’s primary study also reveals a similar trend, as shown in the graph.

In these moments of urgency, farmers resort to System 1 Thinking, which is hasty, instinctive, and often desperate. Many smallholder farmers borrow from multiple sources and must sometimes turn to informal moneylenders who charge steep interest rates. What starts as survival borrowing can spiral into a vicious debt cycle, as they scramble to repay one loan by taking on more debt that eats into their already fragile incomes. Their lives are so precarious that a single failed farming season can trap a household in chronic financial distress without any safety net.

Credit and savings have expanded significantly in rural Bangladesh due to microfinance institutions (MFIs). However, these tools alone are not enough during and after climate disasters. This is where products, such as asset-based microinsurance, can cushion when disaster strikes. Unfortunately, insurance coverage in rural Bangladesh remains negligible. Less than approximately 1% of older farmers have any form of comprehensive agricultural insurance.

Farmers often view insurance with suspicion. Many hear stories of delayed payouts, unclear policy terms, or agents who disappear after they collect premiums. Others consider insurance a bad omen. Insurers have limited rural reach on the supply side. They have a thin distribution channel and slow administrative processes. The insurers are less digitally connected and do not understand claim mechanisms well. The result is a trust gap, and farmers who could benefit the most from insurance are the least likely to buy it.

From the insurers’ perspective, rural markets are hard to reach profitably. Yet, if they partner with MFIs, they can unlock high-volume, low-cost distribution. MFIs already have the network, client trust, and collection systems in place that can lower acquisition costs and improve premium collection rates.

For decades, MFIs have built deep, trusted relationships with rural clients. Farmers see MFI staff regularly to disburse loans, collect them, and for financial advice and support. This trust and accessibility give MFIs an advantage most insurers lack. MFIs can embed microinsurance into current loans or savings products and make them easy to adopt. They can collect premiums and loan instalments at the same time, which would remove the need for separate payments and reduce administrative hurdles. MFI staff can act as facilitators between farmers and the insurers when claims are needed by the farmers. This would help farmers file claims and ensure timely and transparent payouts.

From the insurers’ perspective, rural markets are hard to reach profitably. Insurers can partner with MFIs to unlock high-volume and low-cost distribution. MFIs already have the network, client trust, and collection systems that lower acquisition costs and improve premium collection rates. A partnership between MFIs and insurers can go beyond social impact and serve as a business opportunity for insurers. Therefore, insurers can work with MFIs to expand their customer base, diversify risk pools, and build long-term revenue streams from millions of small but consistent premiums.

Globally, MFI–insurer partnerships have proven effective. In the Philippines, the microinsurance mutual benefit associations (Mi-MBAs) bundle insurance with microloans, which insure more than a million clients. In Indonesia, PasarPolis partners with MFIs and digital platforms to sell affordable, simple insurance products alongside everyday transactions. In India, VimoSEWA combines insurance with social protection and livelihood support for women in the informal sector.

Bangladesh has started to see similar innovations. The Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee (BRAC) has partnered with the Syngenta Foundation, the Green Delta Insurance Company, and the Sadharan Bima Corporation to offer crop insurance to its clients. MSC’s research revealed that when products are simple, affordable, and trusted, farmers are willing to pay the extra premium for their peace of mind. However, the scale remains small, and broader adoption requires MFIs to innovate products, simplify claims, and engage strongly with communities.

In recent years, climate risks have only intensified, while the gap between farmers’ needs and the tools available to manage those risks has widened. MFIs can uniquely bridge that gap to complete the financial protection package with embedded microinsurance alongside credit and savings. For farmers, this financial protection package means the difference between a fresh start after a disaster or years of debt. For MFIs, it can protect loan portfolios and strengthen client relationships. For insurers, it provides a way to access a profitable, underserved rural market at scale. Ultimately, this creates mutual benefits for all the involved stakeholders.

Microinsurance is the missing link in rural financial resilience that can emerge as the gateway to a transformative future for smallholder farmers. When we empower MFIs to deliver microinsurance, we can transform lived experiences from survival toward inclusivity and planned empowerment. It is time to equip Bangladesh’s farmers in Bangladesh with the tools they need to withstand and recover from climate disasters.

Written by

Shahrukh Ahmed Latif

Manager

Leave comments