Digital consumer credit: nano loans, macro problems

by Graham Wright and Martin Holtmann

Sep 8, 2018

7 min

The potential to harness digital footprints and channels to provide rapid access to credit cannot, and should not, be denied. But it will take concerted efforts to optimise the products currently being delivered and realise the full potential of the digital revolution for consumers and providers alike.

Introduction

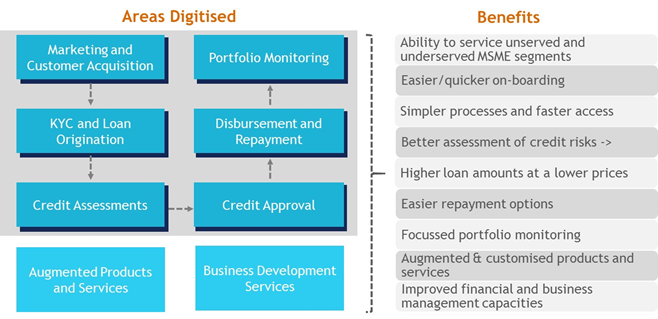

Digital small and medium enterprise (SME) lending offers enormous potential to revolutionise access to credit for small businesses, which form the backbone of so many economies across the globe. With the digitisation of processes, SME businesses can be on-boarded, assessed, and receive a loan within 48 hours. Furthermore, since SME businesses leave much deeper digital footprints than most individuals who take personal consumer loans, this data can indeed to facilitate informed lending decisions. SME loans are typically large enough to allow some form of direct involvement of a loan officer with the borrower, which significantly enhances the chances of the loan being repaid.

Access to small amounts of credit with a few keystrokes can be immensely important and valuable for people facing short-term cash-flow problems or emergencies. This is why digital consumer credit meets an important demand – as the enormous uptake of such products in East Africa has demonstrated. Yet it does carry considerable risks for consumers and the industry as a whole. This blog focuses on digital consumer credit.

Consumer credit has a startling array of similarities to old-style microcredit – and seems set to have to re-learn the same lessons all over again.

| Microcredit | Digital consumer credit | |

| Insufficient or no emphasis on savings | Savings services are only available in a limited number of institutions | Savings services, if available, typically only find use in the assessment of credit risk or loan size. Ironically, many providers offer a good range of savings services as part of their digital credit offering, but these are rarely promoted. |

| Loan amounts are too small to be useful | Most initial loans fall into this category – and so are often used for “non-productive” purposes like settling expensive debts, buying medicine, or sending children to school. Yet thereafter, the subsequent size of loans is typically adequate to finance a very small enterprise. | Most loans offered are too small for enterprise. They are at best suited for basic daily trading activities under which people buy goods at the wholesale market in the morning and sell them during the day. Many such loans are too small to be useful even for health and education expenses. There is increasing evidence that individuals may use such loans for gambling. |

| Borrowing from multiple sources to get a useful sum | As a result of the small size of loans – this “patching” of loans behaviour is common. | As a result of the above – this behaviour of “patching” loans is common – see Give us Some Credit! Meet the Digital Borrowers in Kenya |

| Reliance on repayment behaviour to assess credit risk | Two key risk management systems of microcredit comprise group guarantee and repayment history. Based on these, the institutions offer larger follow-on loans to borrowers. | All consumer credit providers depend above all on credit history, including those based on smartphone apps – see How Smart are Smartphone Lending Apps in Kenya? These providers manage risk by initially lending minuscule amounts and then slowly increasing loan sizes based on the borrowers’ repayment behaviour. |

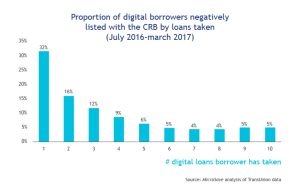

| High drop-outs in initial loans | Default on the first loan cycle is not as high because of group guarantee but drop-out after the first loan is common. This is because borrowers discover that the weekly instalments associated with microcredit are stressful. | MicroSave analysis has shown that 32% of first loan cycle and 16% second loan cycle borrowers default – small wonder that the interest rates are so high to cover this risk! These defaulting borrowers are then excluded from accessing another loan. In Kenya, for instance, more than 10% of the adult population are now negatively listed on the credit reference bureau. |

| One loan used to settle another | This is increasingly common in oversaturated markets but particularly problematic when markets move rapidly from a total lack of credit to very easy access to credit. For example, in the case of Andhra Pradesh in India. | Analysis from Kenya and Tanzania suggests that the use of one loan to settle another increasingly common – see also Give us Some Credit! Meet the Digital Borrowers in Kenya |

| Challenges to managing delinquency | Most efficient microcredit institutions keep their PARs below 5%. | Our analysis shows that digital consumer credit providers lose around 50% (yes, fifty per cent) of the money they lend. Yet they write these loans off quickly to report low NPL/ PAR rates. |

Furthermore, this is not the first time that we have seen consumer lenders try to address the low-income market. In the late 1990s, several domestic and foreign consumer lending companies entered the Bolivian microfinance industry. At the time, it was perhaps the best served and one of the best-performing markets in the world. The highly efficient MFI sector in Bolivia had achieved close to 50% penetration.

Consumer lenders in the country rapidly gained market share by offering quick disbursement loans to salaried employees, as well as to anyone who had earned a good credit score based on their previous or existing relationship with an MFI. The ensuing competition resulted in multiple borrowing, over-indebtedness, and ultimately created a crisis that included a debtors’ revolt. The crisis forced the industry to reschedule or write off massive amounts of debt.

At one point, non-performing loans amounted to more than 20% for some of the lenders. The foreign consumer lenders soon exited the market, leaving it in ruins. It took years for the rest of the industry to recover. See Elizabeth Rhyne’s Crisis in Bolivian Microfinance for a great overview of this.

Microcredit is no panacea but …

For all its faults, microcredit was founded with a clear social purpose to alleviate poverty by nurturing enterprise. Although the idea that microcredit is used exclusively for enterprise is, of course, a marketing myth. Microcredit has been held to account on disclosure and transparency, primarily through MIX Market and investors. It has usually been financed, and held to some account, by donor agencies and social investors who look for financially sustainable developmental impact.

Microfinance has received support from a range of not-for-profit agencies. These agencies seek to safeguard the clients’ interests, for instance, the SMART Campaign. The agencies also seek to monitor or support the social performance of providers, for instance, the Social Performance Task Force. While there is some discussion of the efficacy of these agencies, many providers and their funders regard them to have a legitimate place in the discourse.

The larger for-profit providers of digital financial services are responsible, above all, to their shareholders who did not invest for social returns. As a result, while current players talk about consumer protection, to date they have done less to implement it – even though there are clear commercial reasons to do so. For an instance of this, please see How Can Providers Make Digital Credit More Profitable? and Consumer Protection in Digital Financial Services – Providers Take the Lead. However, with the growing impetus around the SMART Campaign’s FinTech Protects, this may be set to change.

Even today, delinquency rates are appalling, particularly in the early loan cycles (see graph below). However, few providers seem willing to innovate or even deviate significantly from the base M-Shwari model, which rolled out more than five years ago in Kenya. Currently, providers still largely deal with credit risk by raising interest rates. So, for instance, in Uganda, the MTN/Commercial Bank of Africa MoKash product costs 9% per month. This is in contrast to the 7.5% charged for the same product (M-Shwari) in Kenya, where there is a credit reference bureau and, arguably, a better credit culture.

i. Soundness of services;

ii. Security of the mobile network and channel;

iii. Fair treatment of customers

This is an excellent step forward, but there seems little application of the third principle of “fair treatment” to customers of digital credit. These customers are subjected to aggressive push-marketing and have to wade through hard-to-access, complex terms and conditions. These factors drive high levels of delinquency and thus result in high, risk-priced interest rates.

A two-pronged approach is required to address these challenges:

Regulators often pay inadequate attention to this industry because it is of low value and thus does not present a systemic risk. However, the volume or the number of people affected by poor – and indeed often predatory – provider practices, is high. Therefore, there are some the steps they need to take:

- Establish robust credit reference bureaux;

- Require automated data submission systems to ensure consistency of loan or repayment data reported to credit reference bureaux;

- Mandate off-shore, app-based lenders to report to credit reference bureaux;

- Customise credit ratings basis amount and number of days overdue;

- Institutionalise mechanisms for customers to check and correct credit history;

- Provide strong guidance or enforcement on drafting and communicating clear and customer-focused terms & conditions; and

- Limit or ban aggressive push marketing over SMS.

Providers

- Provide clarity on terms & conditions – even for feature phone users. This has been proven to reduce delinquency by nearly a third.

- Re-engineer products to include:

i. Overdrafts – to meet the needs of day-traders and those who require loans for terms shorter than a month. Currently, more than a third of borrowers repay their month-long loans within a week of taking them … but receive no interest rebate.

ii. Higher amounts, longer repayment terms and reduced interest rates that reflect good credit history built over time – so that providers stop placing the burden of the massive delinquency in the early loan cycles onto those that repay on time every time.

iii. Behavioural nudges to minimise imprudent borrowing used to finance gambling, drinking, and even pornography.

iv. Increased human touch (particularly for larger loans) – to respond to the clearly expressed need for human interaction when deciding on whether to buy a product, when there is a problem, or when customer grievances need resolution.

The potential to harness digital footprints and channels to provide rapid access to credit cannot, and should not, be denied. But it will take concerted efforts to optimise the products currently being delivered and realise the full potential of the digital revolution for consumers and providers alike.

Disclaimer – Martin Holtmann is Manager – Digital Finance and Microfinance for the IFC. The opinions expressed in this blog are his alone.

Written by

by

by  Sep 8, 2018

Sep 8, 2018 7 min

7 min

Leave comments