Transforming communication protocols for social assistance programs in Indonesia

by Astri Sri Sulastri and Raunak Kapoor

May 10, 2021

7 min

Effective communication of social protection programs (SPPs) is essential to avoid misconceptions and undesired behavior among beneficiaries, as well as setbacks in implementation. This blog highlights the potential role technology can play in enhancing awareness, socialization, and complaint resolution efforts in the delivery of SPPs in Indonesia.

In response to the COVID-19 crisis, nations across the world launched 1,100 social protection programs (SPPs) to help more than 1.8 billion people. While this looks impressive on paper, often, less than 50% of the intended recipients know of the programs or how to access these benefits.

Effective communication of SPPs is essential to avoid misconceptions, undesired behavior, and setbacks in implementation. For example, poor communication of the rationale behind the program made farmers in India reluctant to enroll for Direct Benefit Transfers in Electricity (DBTE). Designing an effective communication process for social protection programs remains a global issue, more so in times of emergencies like COVID-19, when the assistance needs to reach the most excluded segments quickly and efficiently. In this paper, we present a comprehensive framework for demand and supply-side communication needed between the government and relevant program stakeholders, especially for SPPs announced as part of emergency response during crises.

Social protection programs in Indonesia: The context

The Government of Indonesia (GoI) currently implements more than 80 social assistance programs. Of these, 12 programs were launched or modified in response to COVID-19. These SPPs cover more than 20 million low-income beneficiaries through conditional cash transfers, food staples, and utility bill waivers.

In addition, the GoI has also embarked on the ambitious G2P 4.0 vision to improve the delivery of existing SPPs. The proposed reforms will enable beneficiaries to select their choice of payment service provider and create opportunities for the private sector in the delivery of social assistance. However, this will further add to the complexities of communication around four key building blocks of the proposed vision, as shown below. In addition, a robust and accessible grievance resolution mechanism will also be critical to allow beneficiaries and frontline workers to submit queries and register complaints.

Challenges in existing communication and social efforts around the delivery of social protection programs

The GoI has published clear guidelines for the communication and socialization of its two most significant SPPs—Program Keluarga Harapan (PKH) and Kartu Sembako. The guidelines state that all related information should be delivered to diverse stakeholders. Beneficiaries are the primary stakeholders, while local governments, facilitators,[1] and banking agents or e-warongs are other key stakeholders of these programs. The communication content comprises five major topics – the onboarding process for beneficiaries, transaction with KKS (Kartu Keluarga Sejahtera)[2] cards, confirmation of fund transfer in every disbursement schedule, program-related policies for the beneficiary, and transaction compliances for e-warongs.

Despite such standardized guidelines, challenges persist around awareness, communication, and socialization efforts directed at beneficiaries and frontline workers. For example, MSC’s study on PKH revealed that only 70% of beneficiaries were aware of their exact entitlements. Our most recent study on the impact of COVID-19 on PKH implementation validated these findings. While most beneficiaries were aware of the revised disbursement schedule, a majority of them remained unaware of their modified entitlements.

The existing communication and socialization efforts suffer from the following constraints:

- The education and socialization process relies heavily on in-person interactions between field facilitators and beneficiaries. In addition, such interactions rely on physical aids for communication. This makes the entire process resource-heavy, logistically cumbersome, and difficult to scale.

- Key messages are not enforced properly, which leads to inconsistent communication. Moreover, local context and the perception of field teams can sometimes influence the content of the message.

- Evidence suggests that beneficiaries lack awareness of the resolution process and are ill-equipped to report or manage grievances. Formal grievance resolution systems remain inaccessible for most.

The COVID-19 pandemic has further dampened awareness and socialization efforts. Restrictions on movement imposed to curb the spread of the virus forced the Ministry of Social Affairs (MoSA) to limit in-person interactions between the frontline staff and beneficiaries. Frontline workers, such as PKH facilitators were allowed to conduct regular meetings only in green zones—areas with a low number of COVID-positive cases. MoSA also mandated frontline workers to follow strict health protocols, adjust the verification process, and relax requirements for the verification of elderly and severed disabled beneficiaries. While these measures were important from health protocols standpoint, it also restricted communication efforts in the field, which highlights the need for digital alternatives to program communication.

Can digital channels streamline communication and socialization efforts in SPP delivery in Indonesia?

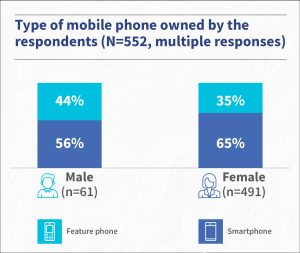

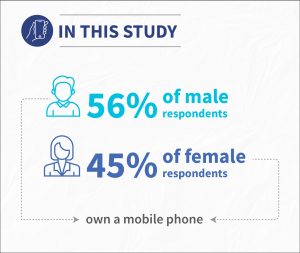

Indonesia has a booming digital economy that is predicted to reach USD 124 billion by 2025, up from USD 44 billion in 2020. Of the 180 million internet users in the country, 150 million are active users and 105 million are service platform users. 84.92% or 70,670 of the 83,218 villages in Indonesia can access 4G network services. A recent study from Google-Temasek-Bain points out that the COVID-19 pandemic has boosted digital adoption, with 36% of first-time internet users in Indonesia. The number of such new users was much higher in non-metro areas. MSC’s most recent study on the impact of COVID-19 on PKH implementation found that around 50% of beneficiaries owned a personal mobile phone, most of which were smartphones.

These numbers indicate an opportunity for the country to utilize digital channels in SPP delivery. Many government agencies in Indonesia have been using technology to streamline their public service delivery efforts. Recently, the Health Ministry of Indonesia collaborated with Facebook and WhatsApp to disseminate structured information about the vaccine for COVID-19 and developed a chatbot to accelerate registration for the vaccination of medical staff. Regulatory agencies, such as OJK and BI have also chalked out ambitious plans to use technology to supervise the financial services sector efficiently.

What potential digital solutions can help streamline communication, socialization, and grievance resolution efforts for the delivery of social protection programs?

- Chatbots powered by artificial intelligence (AI) and natural language processing (NLP)

Policymakers across the globe have increasingly started to use AI- and NLP-powered chatbots to digitize communication with the general population. Modern chatbots use NLP capabilities to understand text communication and respond with either standard messaging templates like FAQs or channel the communication to the relevant live agent for resolution. These chatbots can be hosted on multiple platforms including SMS, web portals, social media platforms, and mobile applications, among others. They can also be connected to multiple databases as well as customer relationship management (CRM) systems to provide real-time information on relevant queries and maintain digital records of communication. During the pandemic, governments across the world used chatbots to deliver behaviour change communication on COVID-19 safety protocols. Countries like Myanmar continue to use chatbots for financial education, especially for micro-entrepreneurs. Policymakers in Indonesia can also consider deploying chatbots, especially to make grievance resolution systems in SPPs more accessible for beneficiaries and frontline workers.

- Social media platforms to communicate with relevant SPP stakeholders and gauge public perception on the effectiveness of SPP delivery

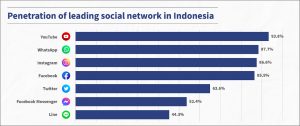

The popularity of social media platforms like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and WhatsApp continues to grow in Indonesia, even among low-income segments.

In this context, the government must invest resources to increase its social media presence on multiple platforms. This will enable transparent two-way communication with relevant program stakeholders. The government can also use social media platforms as channels to share important program updates and educate relevant stakeholders on the aspects of social assistance delivery.

Additionally, Indonesian policymakers can also explore opportunities to gauge public sentiments on SPP delivery by using big data analytics on the social media activity of citizens. Such a solution can serve as critical monitoring and supervision tool and the insights can enable the government to make processes for SPP delivery more efficient. Policymakers across the globe have started to institutionalize such tools to draw important policy insights from the social media activity of citizens. For instance, the Central Bank of Kenya used a sentiment analysis tool to monitor consumer complaints against digital credit providers.

- AI-powered speech recognition technology and outbound Interactive Voice Response (IVR) for oral segments

Social protection programs often target segments that are new to technology and perhaps new to the formal financial system. Many of these beneficiaries are “oral,” and not comfortable with written text. According to our most recent study on PKH, 64% of beneficiaries have completed only primary education. Many of these beneficiaries may be effectively oral. In-person interactions, visual aids, and voice-based technology solutions like IVR are the most effective means to communicate effectively with the oral segments. For instance, the Government of India used a missed-call-based IVR with pre-recorded FAQs to increase the awareness of COVID-19 in rural areas. Indonesia can use similar measures to enhance the effectiveness of its SPP communication and education efforts. In addition to IVR, the government can also explore opportunities to utilize speech recognition or analytics technology to automate and supervise operations at call centers. Though still in the early stages of development, the application of this technology has shown positive results in generating deeper insights into the satisfaction levels of customers and beneficiaries with products and services.

The way forward

As the government continues to expand its existing social protection efforts, it needs to enhance the awareness and communication of these programs. MSC’s guiding principles can be synchronized with digital efforts to ensure that the right information reaches intended stakeholders. The government can use this framework and guide to optimize the implementation of digital communication for social protection programs.

[1] The facilitators for PKH are called PKH facilitators, and those for the Kartu Sembako program are called TKSK (Tenaga Kesejahteraan Sosial Kecamatan)

[2] KKS or Kartu Keluarga Sejahtera is a basic savings account for the delivery of PKH and Kartu Sembako payments to beneficiaries. KKS cards enable beneficiaries to withdraw the benefits received through ATMs, banking agents or e-warongs, and bank branches.

Written by

by

by  May 10, 2021

May 10, 2021 7 min

7 min

Leave comments