Traits of resilient and vulnerable smallholder farmers

by Partha Ghosh, Rahul Chatterjee and Graham Wright

Jan 27, 2023

4 min

Smallholder farmers are vulnerable to climate change in many different ways. We analyzed the lives and livelihoods of different types of farmers to assess how individuals and families either succeed to or fail to adapt to climate change and environmental stresses. We look at the role financial services, education, gender roles and responsibilities, and social norms play to determine resilience to climate change.

“We hear about heavy rainfall two or three days prior. We prepare a kit with ration, tarp, torches, candles, medicines, and other essentials.”—Manoj Kumar, 45, Gannipur Bejha

“We would like to have sufficient savings to deal with the damage post floods, but it is unlikely. So we have to resort to moneylenders.”—Nand Kumar, 61, Gannipur Bejha

Our previous blog looked at the impact of climate change and coping strategies adopted by smallholder farmers in Bihar. This blog uses persona analysis to explore the traits of resilient and vulnerable smallholder farmers, and examine how gender influences the experience and impact of climate events. We highlight three of our respondents from MSC’s qualitative research in two flood-prone districts of northern Bihar.

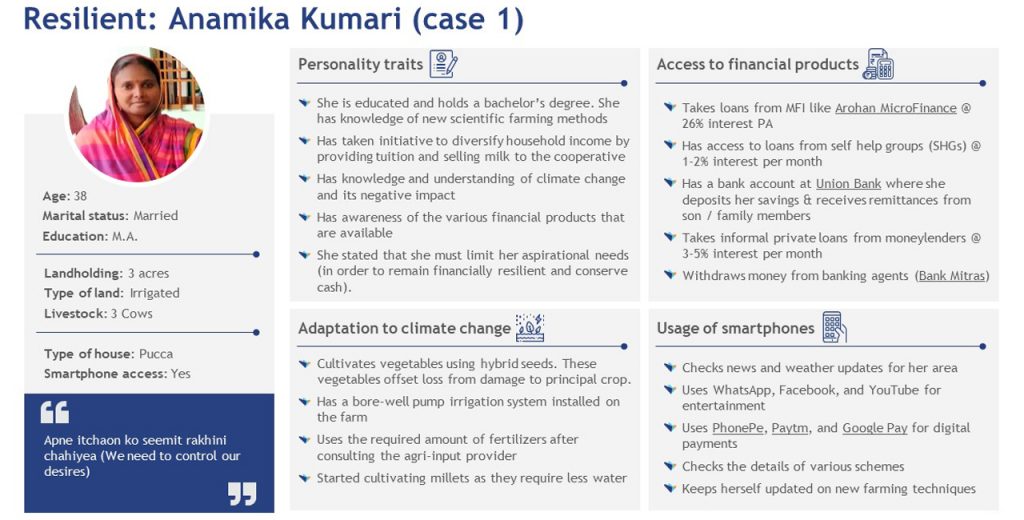

Anamika Kumari highlights how education and knowledge can empower smallholder farmers to adopt important adaptation strategies. These strategies are enabled and strengthened by Anamika’s understanding of, and access to, a range of formal and informal financial services, as well as the internet.

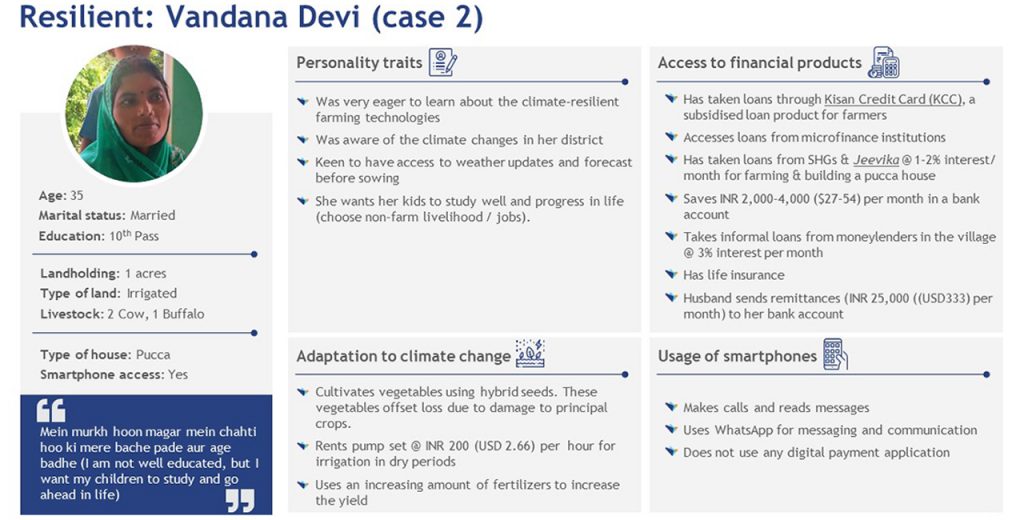

Vandana Devi is not quite as resilient as Anamika. She is acutely aware of the changing weather patterns and knows that these result from climate change. However, she has a limited understanding of the underlying dynamics, such as its causes and likely effects. But she is keen to learn. Like Anamika, she has started growing vegetables to offset losses to her main rice and maize crops, which the floods and pests often damage. Vandana also has good access to formal and informal financial services and uses these as a key part of her adaptation strategy. Her husband has migrated for work and remits money to her each month, allowing her to save and take loans. However, she does not use the internet or digital payments.

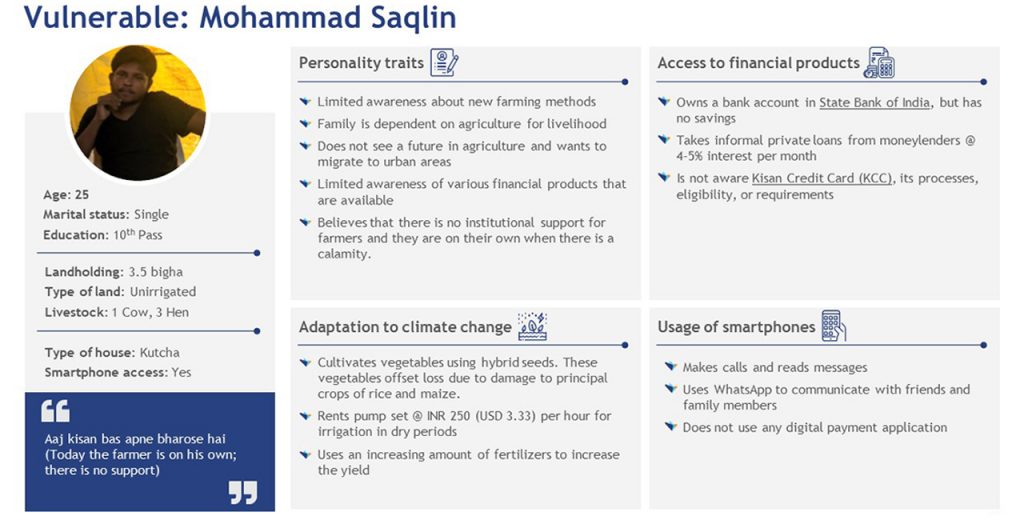

In contrast, Mohammad Saqlin is vulnerable to the impact of climate change. He is poorly educated and has a limited understanding of climate change or new adaptive farming methods. He sees little support for agriculture or a future in it. He is keen to migrate to Allahabad, Lucknow, Kolkata, or perhaps Delhi for work. Despite his poor understanding of new farming practices, Mohammad has already started cultivating vegetables using hybrid seeds to reduce the risk associated with the Kharif season crops of rice and maize. He has a bank account but no savings, and he depends on local moneylenders for his liquidity needs. Like Vandana, he does not use the internet either.

While our female personae are more resilient than Mohammad, they face specific and gendered challenges when responding to climate events. The physical impact of a climate hazard is the same for both genders. However, uneven exposure to hazards and socioeconomic inequalities result in a disproportionate level of climate vulnerability among men and women.

The unpaid household work of women becomes significantly more arduous during floods. Wet wood and biomass used for fuel mean that cooking meals for the family will take more time. Furthermore, waterborne diseases mean that women must boil their family drinking water to purify it—an additional responsibility prolonged by damp fuels. Women also report increased caregiving activities due to heightened incidences of waterborne diseases and disrupted sanitation facilities. They also note that it takes more effort to prepare and feed dry fodder to livestock stranded above the waters.

The disruption of sanitation facilities further complicates these increased household chores, which affects women disproportionately and exposes them to infections. Women also report increased stress as they struggle to repay loans taken from MFIs and SHGs during and after floods. Respondents noted that MFIs are not empathetic toward their borrowers and will collect their money by all means. Increased physical labor, an increased risk of infections, and the stress of managing household finances are likely to threaten women’s long-term health.

In some cases, women relocate to their maternal homes or to relatives’ houses with their children and elderly relatives to try to ensure their safety.

Of course, men are also affected by floods. Men help their family members relocate and arrange food, medicines, and shelter during the floods. They brave water-logged roads to access these necessities and, when necessary, take the risk of borrowing from moneylenders. They report increased mental stress due to incidences of diseases, loss of assets, and uncertainty of recovery from the calamity.

Thus, during floods, women tend to play a defensive role, seeking to ensure the sustenance and health of family members. In contrast, men play the role of providers, reflecting their social norm-derived greater ability to travel and interact outside the household and village. We did not observe any shift in the roles and responsibilities of women and men. Essentially, these lines of response are pre-defined by societal norms.

Our next and final blog in the series will examine the seven key factors that determine the resilience and adaptive ability of smallholder farmers in Bihar.

by

by  Jan 27, 2023

Jan 27, 2023 4 min

4 min

Leave comments