MSC assisted the Bangladesh Bank in charting a roadmap toward building a cashless economy by 2031. Despite widespread account ownership, digital usage remains constrained by literacy, affordability, trust, and infrastructure gaps. The roadmap defines 12 strategic goals, including reducing transaction costs, expanding connectivity, enabling interoperability, strengthening consumer protection, and promoting inclusion. These coordinated actions will accelerate adoption, enhance economic participation, and drive Bangladesh’s transition to a fully digital economy.

Blog

Scoping study to support the Bangladesh Bank to scale digital transactions in Bangladesh

The study, conducted in Singair Upazila as a microcosm, examines Bangladesh’s transition toward a cashless economy. It highlights widespread infrastructure for DFS but low-value digital transactions. Findings show adoption varies by occupation, with salaried personnel and traders leading, while farmers and daily laborers lag. Key barriers include high transaction costs, low digital literacy, trust concerns, limited merchant acceptance, and infrastructure gaps, even though DFS is valued for its convenience and efficiency.

From prayers to power: Scaling climate-smart agriculture through inclusive finance

In the quaint village of Thiruppachethi in Tamil Nadu, 46-year-old farmer Jayanti Amma often grappled with the uncertainties of the Samba season. Her livelihood depended on erratic rainfall and the Vaigai Dam’s water politics.

Jayanti is not alone. Countless farmers just like her across India struggle with the escalating impacts of climate change. Erratic weather patterns, such as prolonged droughts and unseasonal downpours, have led to frequent pest outbreaks, sharp yield losses, increased input costs, and post-harvest losses, which lead to falling incomes. Studies suggest average farm incomes have dropped by 15–18%. Some sectors report losses up to 25% due to unpredictable climate changes.

Climate-smart agriculture as a path to resilience

Jayanti Amma’s fortunes began to change when the local inclusive finance institution (IFI) she had been with for eight years introduced livestock loans. She and her sister-in-law purchased buffaloes for milk production. She also started to cultivate flowers along with paddy through technical support from a state-run agricultural unit.

This shift toward diversified, integrated farming brought her greater income stability. She now sells milk to a local dairy cooperative, uses paddy husk and cow dung as manure for floriculture, and markets flowers in Madurai’s bustling flower bazaar. She now has multiple sources of income, which enables her to meet each season’s uncertainty with renewed confidence. “I still look to the skies and pray for rain,” she says, “but I am no longer afraid.” Her story reflects how climate-smart agriculture (CSA) is the quiet transformation in rural India that protects our vulnerable farmers from unpredictable climate hazards.

For millions of smallholders like Jayanti Amma, CSA offers a pathway to withstand climate shocks. Promising technologies such as drip irrigation, solar pumps, no-till farming, and biodigesters can boost resilience by promoting water conservation, restoring soil health, and diversifying farmer incomes. Yet for many smallholders, especially women, these solutions remain out of reach due to the high upfront costs and limited access to finance.

Can IFIs bridge the climate resilience gap?

Inclusive Financial Institutions (IFIs) are well-positioned to catalyze CSA adoption, especially among smallholders. With deep community linkages and the ability to channel capital where it is most needed, IFIs can help close the resilience financing gap, (CGAP’s recent paper reinforces the same).While a few IFIs have piloted CSA-linked products, most IFIs’ engagement remains peripheral, limited to small-scale experiments that lack institutional commitments or clear pathways to scale.

We propose a three-level approach to get IFIs to commit and chart a pathway to scaling CSA adoption. While the strategies below focus on CSA, this template can be adapted to build resilience in other sectors, such as WASH, housing, and electric mobility. The three-level approach focuses on how to:

- Enable access to climate-aligned capital for IFIs.

- Reengineer IFI products and processes.

- Strengthen ecosystem-wide support across the supply and demand sides for CSA.

1. Enable access to capital for IFIs

IFIs need access to wholesale climate-aligned debt, such as concessional loans, guarantees, blended finance, and climate-focused equity capital to deliver resilience-linked financial services, guided by green and adaptation lending mandates. This represents a significant, but largely untapped, opportunity for multilateral climate funds.

Encouraging examples of CSA financing are emerging in India, partnerships, such as Pahal-GAWA Capital, Encourage Capital-Annapurna, GiZ-Caspian-Sadhan, Annapurna-Credit Agricole CIB-Grameen Crédit Agricole Foundation, and IIX-Samunnati, show early traction in CSA financing. Institutions, such as the Agri3 fund and Rabo Foundation, which offer risk-sharing mechanisms, reduce lending risks for IFIs and complement these efforts. Globally, the International Finance Corporation (IFC) has invested USD 100 million each in debt and equity in Equity Bank (Kenya) and Banco ABC Brasil S.A. for CSA finance.

However, several ecosystem gaps persist, such as the absence of standardized CSA taxonomies and reporting frameworks, limited access to granular climate-agriculture data, and a lack of cost-benefit analyses for CSA products. These foundational gaps hinder the efficient flow of capital into IFIs. On an encouraging note, the Government of India’s draft climate finance taxonomy and the RBI’s Green Deposit guidelines are progressive steps that can help release more climate-aligned capital for CSA.

2. Product and process reengineering at the IFI level

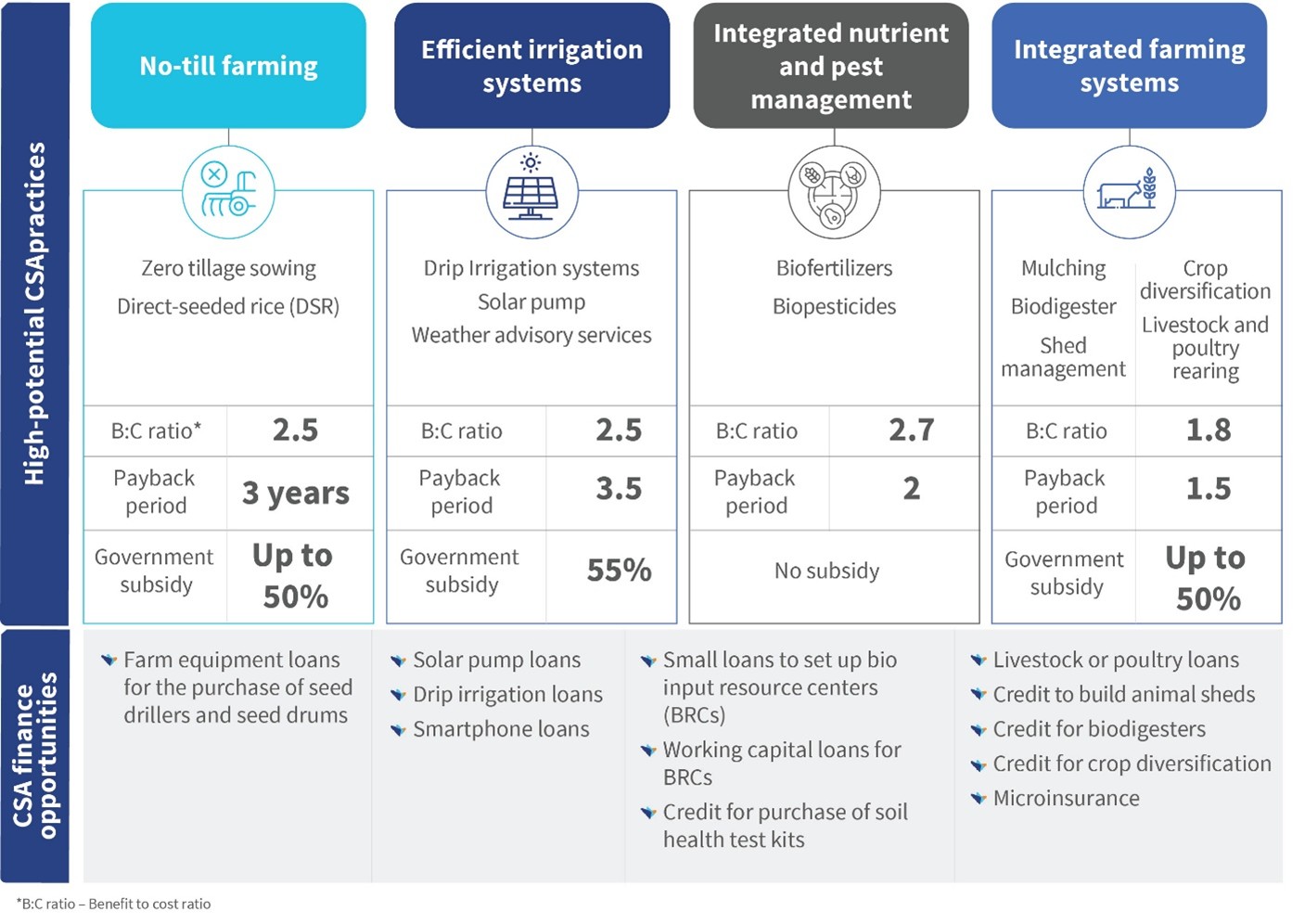

Progressive IFIs, such as Pahal, Annapoorna, and Midland, are moving beyond traditional loans to pilot innovative financing for CSA assets, such as solar pumps and biodigesters. MSC’s research with AGRI3 across three Indian states highlights several pathways for IFIs to scale CSA lending to support high-potential CSA practices, as illustrated in Figure 1 below.

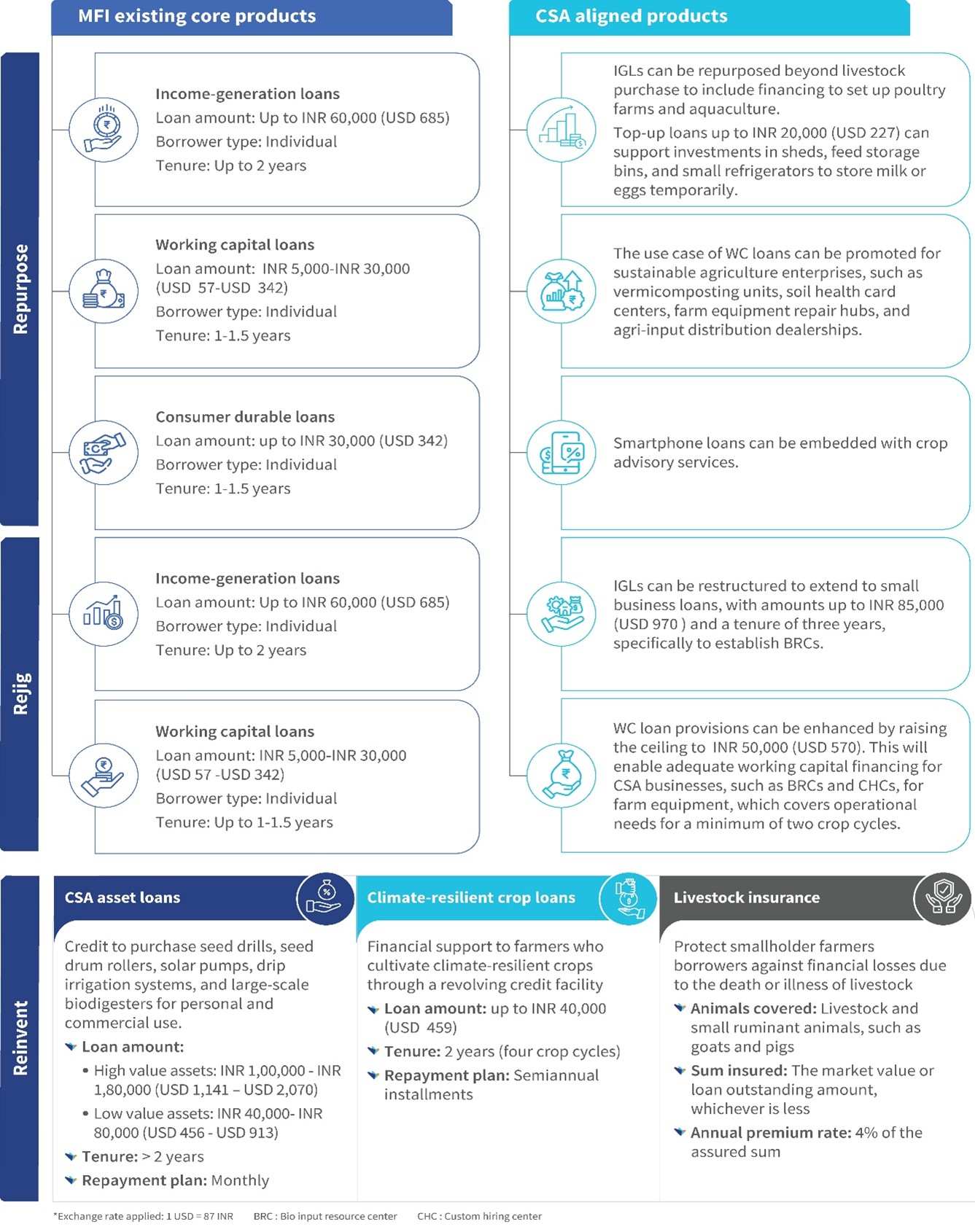

We also identified the CSA financing opportunities for IFIs based on an analysis of their current product portfolio. We proposed that IFIs can adopt one or a combination of three product strategies: Repurpose, Rejig, and Reinvent, to support high-potential CSA practices, as illustrated in Figure 2.

- Repurpose the existing loans for income-generation (IGL), working capital (WCL), and consumer durables to finance smallholders’ investments in backyard poultry, aquaculture, vermicomposting, soil testing, CSA equipment repair centers, and smartphones bundled with digital agri-services apps. Additionally, IFIs can extend top-up loans to support the ancillary financing needs of livestock borrowers.

- Rejig existing loans to support income diversification and resilience. Redesign IGLs by increasing ticket sizes and tenure. This approach would finance business resource centers (BRC) that distribute organic fertilizers in local markets. IFIs can raise the ceilings of WCLs (Working capital loans) to support CSA enterprises, such as BRCs and custom hiring centers (CHCs), that provide farm equipment for rent. This would ensure their operational viability across at least two cropping cycles

- Reinvent products such as asset loans to help smallholders acquire CSA assets such as drip irrigation and bio-digesters. IFIs can provide crop loans to support a shift to climate-resilient contingent crops. IFIs should expand offerings to include livestock insurance for enhanced climate risk mitigation through partnerships.

To strengthen the full credit cycle—outreach, assessment, disbursement, tracking, and risk management—IFIs should collaborate with agritechs (for farm-level data), for performance-based incentives (despite some concerns), government schemes, Original Equipment Manufacturers, and social enterprises. Additionally, IFIs need to invest in three core areas:

- Staff capacity building: IFIs can improve staff capacity through training on CSA appraisal tools. Institutions, such as the National Institute of Bank Management and Sa-Dhan, already offer programs for IFI staff to deploy green and CSA finance.

- IT system upgrades: IFIs can handle flexible loan tenures, differentiated pricing, and adaptive risk scoring for CSA lending.

- Operational de-risking: IFIs can use geotagging, the Internet of Things (IoT), and machine learning tools for real-time CSA monitoring.

These interventions will raise awareness of climate risks within IFIs, equip them to respond actively, and address the gaps highlighted in this MSC–Sa-Dhan study.

3. Ecosystem efforts to prime both the supply and demand sides

Scaling CSA finance requires a supportive ecosystem that empowers farmers, nurtures innovators, and builds financing pipelines. Some promising initiatives include:

- Grassroots programs, such as the NRLM’s Krishi Sakhi initiative and the Tata Trusts’ Lakhpati Kisan, which integrate CSA into rural livelihood programs.

- Startup incubators, such as ThinkAg, AgHub, and a-IDEA, which offer mentorship and seed capital to CSA innovators.

- Government innovation challenges and digital platforms, such as Agri Stack, which support product development, pilot testing, and scale-up through data access and public-private partnerships.

- Blended finance facilities, such as NABARD’s AgriSURE Fund, which supports growth-stage agri-startups with patient capital, technical guidance, and market linkages.

From pilots to scale

As climate change erodes borrower incomes, especially among smallholders and microentrepreneurs, IFIs can feel the strain on their credit portfolios. Diversification into resilience-linked products such as CSA offers a dual opportunity to strengthen customer resilience and expand their own product offerings. IFIs can lead a new wave of climate-smart finance where prayers persist, but power returns to farmers like Jayanti Amma. The shift has begun, quietly but surely, in villages like Thiruppachethi.

A USD-1.5 trillion opportunity: Inclusive finance for climate adaptation

In today’s world, we do not have a shortage of ideas for climate adaptation. We have an excess of talk and a shortage of delivery. Public money, while valuable, cannot bridge the massive USD 187–359 billion gap to finance climate adaptation on its own. We need to mobilize private finance at scale. And we need to do it where climate change’s impacts are felt most acutely: In local governments, micro and small enterprises, smallholder farmers, and particularly vulnerable households.

What the need looks like on the ground

The Findex 2025 report highlights what we at MSC have seen for ourselves. Climate shocks are now routine for low-income communities. 35% of adults in low-income countries report that they suffered a natural disaster or weather shock in the past three years. Two-thirds of these adults lost income or assets, while the poorest 40% were one-third more likely to be hit than others.

Yet interestingly, three in four people affected already have an account with a financial service provider. That combination of high exposure and financial access provides a real opportunity to move beyond talk and into action.

If we are to target finance effectively, we must separate local adaptation needs into three distinct but mutually reinforcing buckets:

- Local governments that build resilient infrastructure;

- MSMEs and smallholder farmers who adapt business models and assets; and

- Households that absorb, anticipate, and adapt to shocks.

Local governments: capital at scale, closer to citizens

Counties and municipalities shoulder the work on infrastructure, which includes flood defenses, water systems, heat management, resilient roads, irrigation, and waste-to-value plants. This infrastructure provides the foundation on which MSMEs and agriculture depend. For these projects, local governments need well-structured, long-term finance.

Green municipal bonds, for example, have financed water storage and flood defenses, such as Cape Town’s USD 83 million issue in 2017, which was oversubscribed four times. Meanwhile, Kenya’s County Green Preparation Facility bundles county pipelines, runs feasibility studies, and prepares projects for local capital markets, including potential green bond issuance. Such aggregation reduces transaction costs, raises bankability, and keeps accountability local, without the often-debilitating challenges of foreign exchange risk.

MSMEs and agriculture: the overlooked engine of resilience

In low-income countries, MSMEs and smallholder farmers employ around 70% of the workforce. Yet they receive just around 2% of global climate finance. We cannot afford this mismatch, especially since MSMEs and the agriculture sector are the “missing middle” of climate finance and often provide periodic employment to the most vulnerable households.

The great news is that we already have an effective delivery system in the shape of inclusive financial service providers (IFSPs), which comprise microfinance institutions, cooperatives, banks, and mobile-money providers. IFSPs serve people from the low- and moderate-income segment every day, at scale, with trusted, transparent systems built over the past 50 years. They already lend about USD 1.5 trillion a year to small businesses. We need to use that infrastructure and take advantage of that remarkable private sector capital base for locally-led adaptation … and thus make every climate dollar go further.

MSMEs and smallholder farmers need a range of products that span working capital and capex loans, savings, insurance, and digital payments. With the right tools, they can turn recurrent shocks into manageable risks through investments in drought-tolerant seeds, solar pumps, raised homesteads, boreholes, and engagement in diversified livelihoods.

Blended finance, which comprises first-loss guarantees, concessional credit lines, and derisking insurance, has already unlocked private lending to MSMEs in programs, such as Ghana’s Boosting Green Employment and Enterprise Opportunities. Toolkits are now available to help IFSPs design climate-responsive products for these needs.

Particularly vulnerable households: Social protection plus inclusive finance

The poorest households often lack borrowing capacity and need grants and timely cash to rebuild and adapt. Targeted social protection (including disaster compensation) and community-level adaptation funds are essential. After the shock of COVID-19, governments have been working to digitize payments, cut leakage, and speed up the delivery of help to those in need.

Well-designed programs, such as the KALIA initiative in India’s Odisha state, blend transfers, insurance, and interest-free loans so families can adopt improved seeds and diversify their income. Social protection and inclusive finance are complementary pathways for these people to build resilience.

The hidden $1.5 trillion channel—still mostly climate-agnostic

The network of IFSP worldwide reaches deep into vulnerable communities, knows clients, and already moves money with systems that regulators trust. Three in four adults in low- and moderate-income countries now can access formal financial services.

However, most IFSP lending remains climate-agnostic, which is a significant missed opportunity. Unless we pair scarce public and philanthropic dollars with this channel, we will not be able to take advantage of local capital markets, crowd in private finance, and increase lending for adaptation.

A rising risk we must manage

Ignoring climate risk will not make it go away. MFIs and banks are already seeing higher portfolio-at-risk where floods, droughts, and storms intensify. In Pakistan, after repeated flooding, many MFIs reduced or even stopped lending in the hardest-hit districts. In parts of Africa, MSC’s scenario analysis, based on climate projections, suggests PAR could double in three years without adaptation support. If we do not de-risk IFSPs with blended finance, many will retreat from high-vulnerability areas.

So, what can concerned stakeholders do in this situation? Here is our eight-step agenda to manage the risk of climate adaptation finance:

An eight-step practical agenda

- Support regulatory provisions that allow innovations in climate finance. Create time-bound innovation windows to test new climate-finance instruments. Use regulatory sandboxes, fast-track approvals, and proportionate compliance for pilots. Build in safeguards to prevent misuse, and reward proven innovations that direct capital to underserved, climate-vulnerable sectors.

- Aggregate projects for local governments. Replicate Kenya’s County Green Preparation Facility model: prepare pipelines, standardize documentation, and bundle smaller projects to reach capital markets—including green municipal bonds, while technical partners manage feasibility, procurement, and ESG.

- Create adaptation guarantee windows for IFSPs. Create funds to offer pooled first-loss and pari passu guarantees to support lending to MSMEs and smallholder farmers for adaptation; structure them to reward lending in high-vulnerability districts and penalize green-washing.

- Provide concessional, climate-tagged credit lines. Channel low-cost capital to IFSPs that commit to product innovation, such as pre- and post-disaster credit, seasonal grace periods, emergency “pause and extend” options, larger and longer tenor loans, and asset-backed financing for adaptation.

- Build the product toolbox. Cofinance research and development and rollout of flexible loans, parametric insurance, and hybrid savings-credit products mapped to anticipatory, adaptive, and absorptive capacities. BURO-Bangladesh’s portfolio shows how standard loans, emergency loans, disaster loans, and contractual savings can be refined to meet a range of climate-driven needs.

- Provide contingent liquidity. Establish disaster-linked liquidity facilities that automatically extend line-of-credit top-ups to accredited IFSPs after a trigger event; quick liquidity prevents clients from being compelled to sell assets and protects IFSPs’ solvency post-shock.

- Layer social protection with finance. Pre-register poor and climate-exposed households, digitize IDs and accounts, and build shock-responsive cash triggered by forecast and satellite indices. Tie grants to optional top-ups, such as low-premium insurance or savings matches, through existing IFSP rails.

- Hold ourselves to LLA principles. Use IFSPs to deliver patient and predictable finance, invest in local capabilities, use community networks to improve risk diagnostics, and double down on transparency and accountability built into inclusive finance over decades. Public money should crowd in private capital and not crowd it out.

This agenda uses the systems and pipes we already have. The IFSP rails that already move value to and from the last mile. It aligns incentives: IFSPs grow sustainably, clients get products that respond to rapidly evolving climate realities, while public funders see measurable leverage. The Green Climate Fund has demonstrated meaningful leverage ratios of up to 1:5.5 for blended finance. With appropriate structures, similar multipliers are achievable through the IFSP network.

The call to action

The adaptation finance conversation often revolves around the same old problem: too little money and not enough absorption capacity. Inclusive finance gives us a way to address both. The network is built, many of the clients are on-boarded and the regulators are already engaged. Now we must repurpose this infrastructure for climate adaptation and thus enable resilience.

Today, we stand at an inflection point. We can either keep talking about the gap in finance for adaptation or use the inclusive finance system we have spent five decades building to close it. We must now unlock the USD 1.5 trillion already flowing each year through IFSPs, blend it with public de-risking, and deliver locally-led adaptation at the speed and scale the climate crisis demands.

Financing growth in tough times: Climate resilience for MSMEs in Kenya

Microfinance institutions must go digital-first, but what holds them back?

Of late, microfinance institutions (MFIs) have been in the news for a variety of wrong reasons. However, for millions of Indians across the country’s far corners, MFIs have stood as a firm backbone of financial inclusion. Yet these vital lifelines face a crisis. MFIs have been struggling with ever-growing cases of default, increased operational inefficiencies, and deepening customer distrust. As pressure mounts on MFIs to stay afloat, they are being pushed to go “digital-first.” But what does that really mean—and why does it matter? We assert that the path ahead will open if MFIs embrace their community-centered model, but reimagine it through digital transformation. The question is no longer whether MFIs should go digital-first, but how quickly they can transition. When we speak of digital-first MFIs, we do not mean replacing loan officers with apps. True digital transformation requires a ground-up redesign, not just digitization of existing processes, from loan origination to collections. This approach uses technology to enhance customer experience, cut operational costs, and provide real-time insights while preserving MFIs’ core strengths: community-based lending and group solidarity. Consider the parallel transformation we witnessed when UPI revolutionized payments and Jan Dhan accounts changed banking for underserved populations. Both succeeded because they reimagined entire processes rather than simply automating existing ones. MFIs need the same fundamental shift.

Despite clear benefits, most MFIs remain trapped by fear. Their concerns are legitimate: borrowers value face-to-face interactions, technology investments appear daunting, and staff resist workflow changes. MFIs particularly struggle with unclear returns on investment and generic tech solutions that demand expensive customization. Yet this hesitation grows costlier by the day. Every month of delay means higher operational costs, increased defaults, and deeper customer distrust. The year 2024 has been particularly challenging. The total microfinance loan portfolio dropped by ₹58,667 crore—from ₹4,33,697 crore as on March 31, 2024 to ₹3,75,030 crore as on March 31, 2025. Even listed MFIs reported severe pressure in Q4 FY25 (ending March 31, 2025), with several posting either losses or sharp declines in profit. Similarly, as per the MFIN Micrometer (Q4 2024–25), the loan amount disbursed has declined by 16.9% year-on-year, while the number of new loans disbursed has dropped by 25.4%. While multiple factors contributed—including deteriorating asset quality, rising credit costs, and borrower overleveraging—many experts point to deeper structural issues: a saturation of agent-led efficiency, limited underwriting capacity due to poor digitization, and continued overreliance on field teams for customer sourcing and engagement.

The belief that customers resist digital solutions is a myth that ecosystem actors must dispel. Rural and semi-urban customers who use UPI, access PM-Kisan benefits digitally, and consume content in local languages are not technology-averse. They need intuitive, low-literacy-friendly interfaces that reflect their preferences. MFIs can build trust-based digital solutions for customer onboarding, repayment tracking, and grievance resolution. Technology exists. Yet, the will to deploy it is perhaps lacking. Regulators hold the key to unlock sector-wide transformation. The RBI and SIDBI can de-risk innovation through grant-backed sandboxes and catalytic capital for early-stage pilots. They can accelerate adoption by nudging MFIs toward existing public infrastructure, including account aggregators, Aadhaar eKYC, UPI123, and DigiLocker. Most critically, regulators can enable safe data-sharing between MFIs and FinTechs for better underwriting, even as they promote shared infrastructure, such as sector-wide consent managers and collection aggregators. Such support will reduce costs and create network effects that benefit the entire sector.

RBI’s recent revision in the definition of qualifying assets — reducing the threshold from 75% to 60% — presents a fresh opportunity for MFIs to adopt a digital-first approach and expand their presence in segments such as personal credit, agricultural finance, and MSME lending. Digital transformation succeeded in other sectors by enhancing human connection rather than replacing it. The telecom industry transformed access with prepaid models. Healthcare boomed with telemedicine and e-pharmacies during COVID-19. AgriTech now enables farmers to sell online and monitor weather through apps. In each case, technology amplified human potential rather than substituting for it. MFIs can follow the same path. Several trigger points demand immediate action from MFIs. Rising nonperforming assets require early warning systems, customer churn calls for data-backed engagement, and regulatory nudges push digital traceability requirements. The transition does not need to happen overnight, but MFIs cannot afford to delay further. They can start with digital group onboarding, predictive collections, or consent-based credit scoring. But they must begin now, guided by a clear vision of creating digital-first, customer-centric institutions that retain community roots.

Three fundamental shifts will determine success in this transformation. MFIs must move from vendor-driven to sector-led innovation to take control of their technology agenda rather than accepting generic solutions. They must shift from digitizing for compliance to digitizing for customers, which will ensure digital tools solve real customer problems rather than merely satisfy regulatory requirements. Finally, they must transform from one-time pilots to build continuous problem-solving capabilities and make innovation an ongoing organizational strength rather than a sporadic project. India’s MFIs stand at a digital inflection point today. They can cling to legacy models and risk obsolescence or embrace transformation with courage and clarity. The path forward demands collaboration between MFIs, regulators, and technology providers. The obstacles are real, but the alternative of gradual irrelevance in an increasingly digital economy is far worse. For millions of Indians who depend on microfinance, the stakes could not be higher. The time for incremental change has passed. The moment for transformation is here, and the country’s people cannot wait.

This was first published on CXOtoday.com on 12th September, 2025