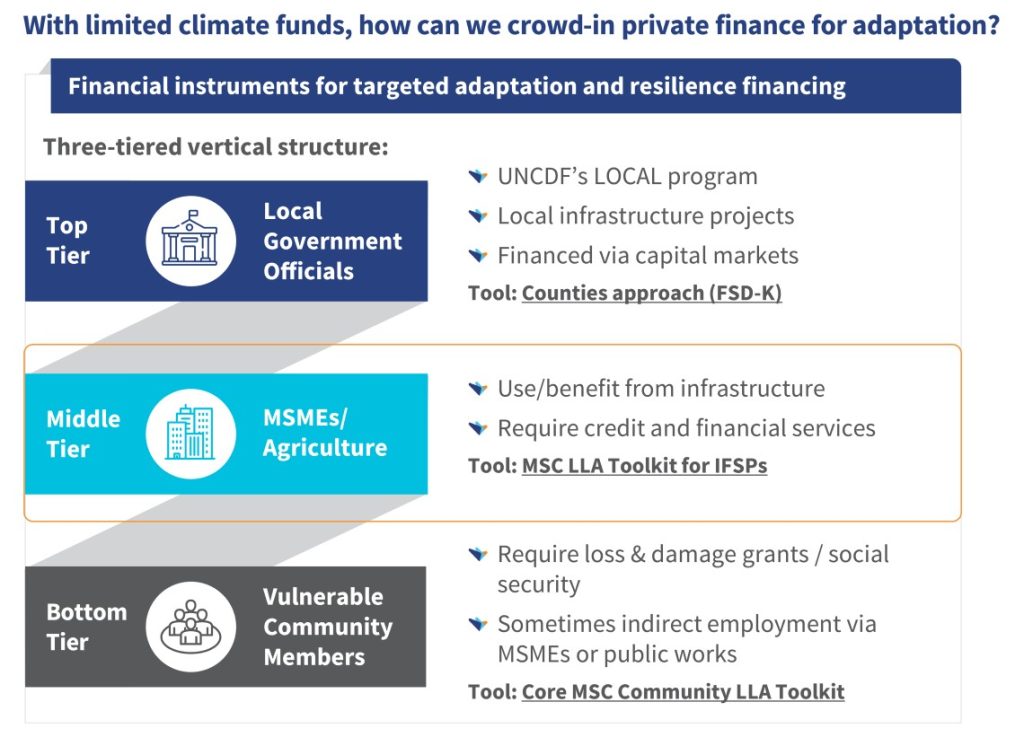

Funds for climate adaptation in the public sector are increasingly shrinking, which raises the question: How do we mobilize private finance for adaptation today? At MSC, we are clear that an immense opportunity lies in the delivery of adaptation finance to micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in the agriculture and allied sectors. These MSMEs are already served by banks, microfinance institutions (MFIs), cooperatives, and mobile money providers—and this is where scale is possible right now.

The 2025 Findex data paints a stark picture, but also presents a clear path forward. In low-income countries, 35% of adults report experiencing a natural disaster or extreme weather event in the past three years. The poorest 40% are about one-third more likely than the better-off to be hit. Moreover, among those affected, large majorities report losing income or assets.

At the same time, about 75% of adults in low- and moderate-income economies have an account with a bank, microfinance institution (MFI), cooperative, or mobile money provider. While the pathways to reach people already exist, the need for financial services is high and unequal.

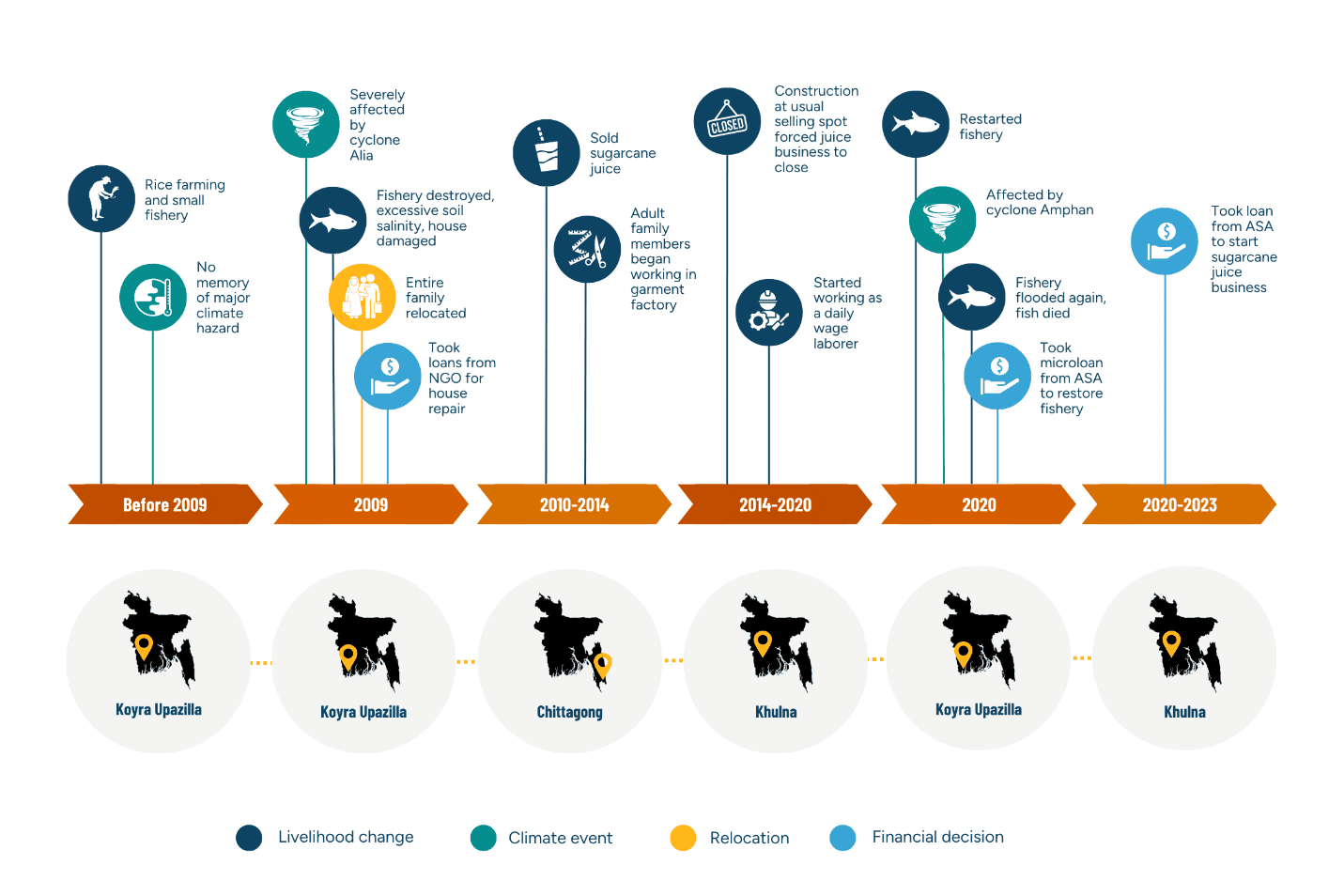

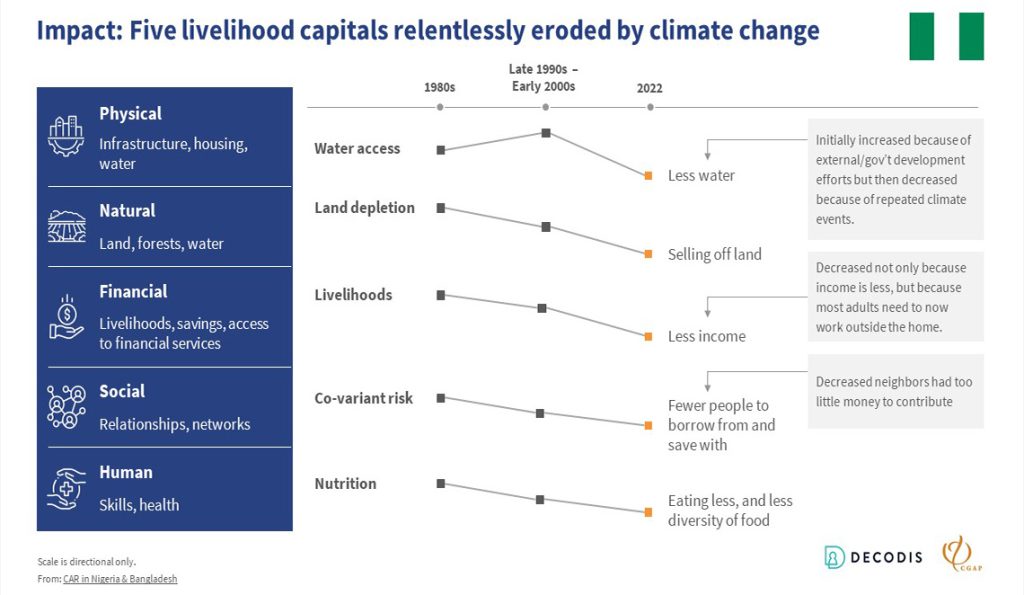

Let us ground this in lived experience.

In our work with the Consultative Group to Assist the Poor (and Decodis, we used MSC’s time series tool to assess the impact of climate change on the five livelihood capitals of farmers over the past 40 years. The relentless erosion of nearly all types of capital shows how climate change is already reversing decades of progress and development.

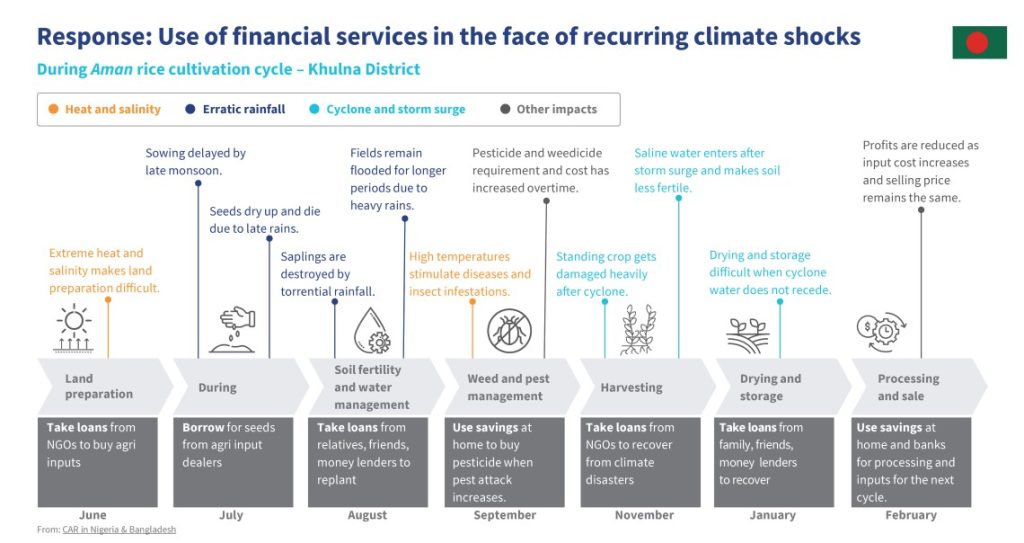

MSC’s work for CGAP in cyclone-hit Khulna shows how climate events have steadily eroded the Aman rice cycle. Delayed monsoon and heat stress fuel pest outbreaks, heavy downpours flatten seedlings, cyclonic storm surges push saline water onto fields, while prolonged flooding prevents drying and storage. This increases input costs and squeezes profits.

Affected households then must stitch together informal and formal finance. They are forced to borrow, draw down savings, and resort to other coping measures to ride out successive shocks to the area’s most valuable crop.

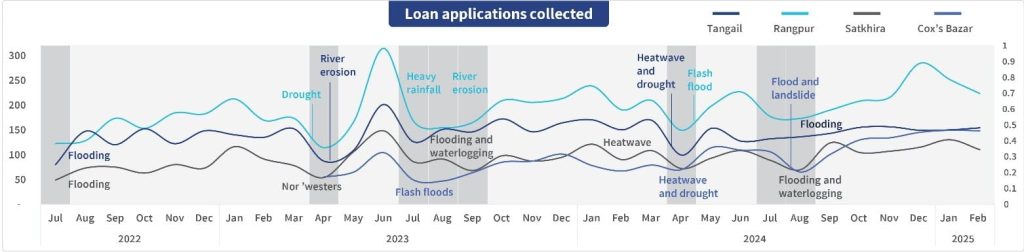

Extreme climate events are affecting FSPs’ portfolios

Across Bangladesh, India, and Uganda, one pattern is hard to miss: Repayments slip when extreme climate events occur. Our work with an MFI in Africa revealed that climate shocks hit roughly a quarter of clients, and as a result, the 30-day portfolio-at-risk (PAR30) increased by about 0.5–1.0%. When we look forward, local drought projections imply income reductions of 15–20%, which is sufficient to add a further 1.2–1.6% to PAR30 unless product design and restructuring rules change.

Similarly, data from Basic Unit for Resources and Opportunities of Bangladesh (show how PAR rises after each extreme climate event in high-risk districts, such as Tangail, Rangpur, Satkhira, and Cox’s Bazar. Climate is no longer just an obligatory corporate social responsibility talking point. Today, it affects the profit and loss of financial service providers.

As a result, we are beginning to see financial service providers withdraw from or limit lending to climate-affected communities. And that is where MSC’s Repurpose–Rejig–Reinvent (3Rs) framework comes into play.

What can inclusive financial service providers (IFSPs) do?

A handful of IFSPs are modifying their product suites using MSC’s 3Rs framework to respond to climate change-induced events in both Asia and Africa. In the following sections, we examine two such instances:

Case 1: MSC’s work with BURO-Bangladesh to enhance climate resilience for customers

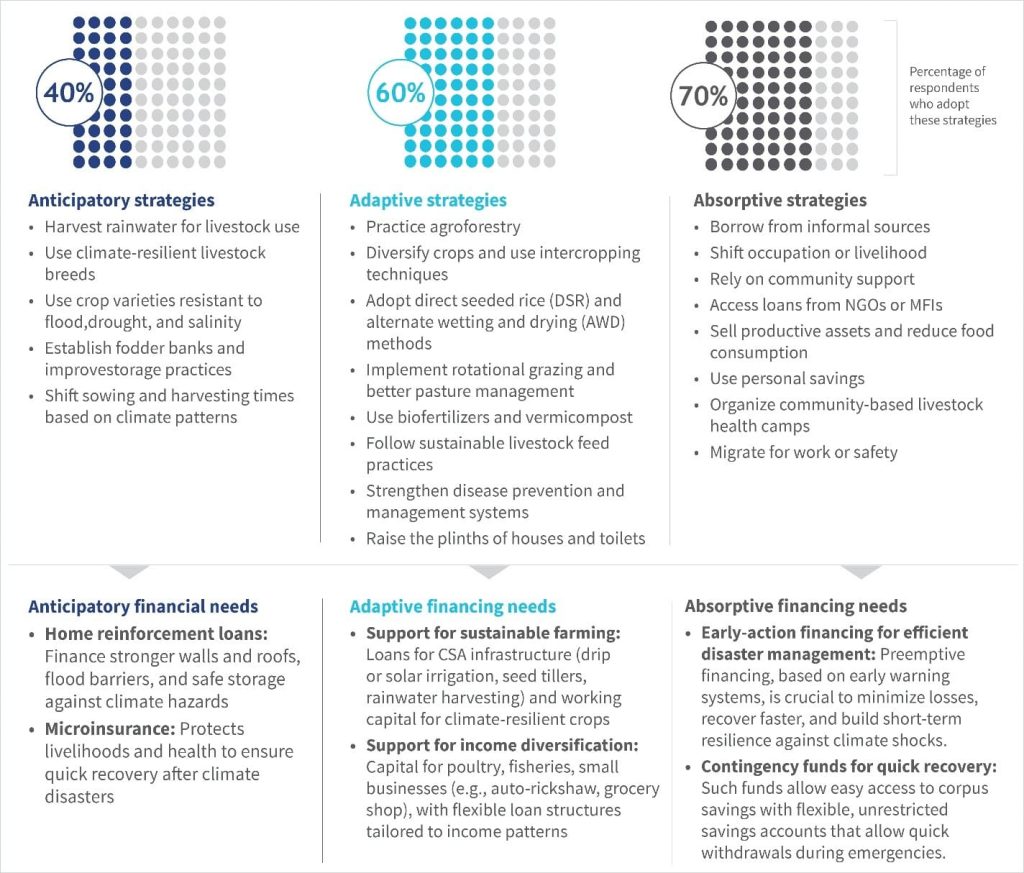

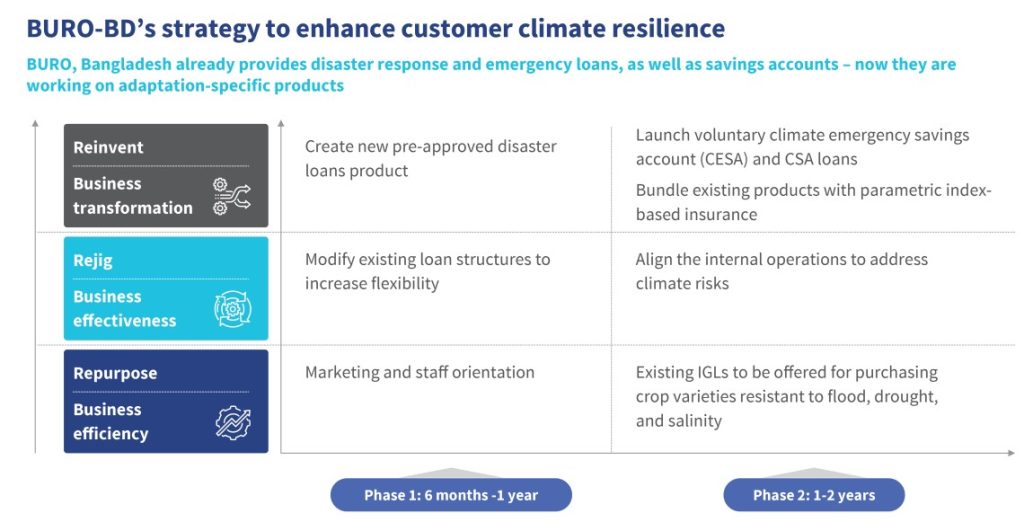

BURO Bangladesh is moving beyond relief by applying a 3Rs strategy to make its products even more climate-responsive:

- Repurpose: Through this part of the strategy, BURO will steer existing products toward adaptation and resilience. It will reorient staff, and thus communications and marketing, around clear climate use cases for its existing products. It will also actively use income-generation loans to finance climate-resilient seeds and inputs.

- Rejig: BURO will use this part of the strategy to tweak loan structures and operations to fit climate realities, including season-aligned repayment schedules, and introduce the flexibility to allow temporary pauses or top-ups after verified shocks. It will also use the rejig part of the strategy to establish early-warning standard operating procedures, supported by MIS tags to enable branches to act quickly and consistently. This will improve BURO’s business efficiency.

- Reinvent: BURO will use this component to develop, test, and launch purpose-built, climate-focused offerings. These would include pre-approved disaster loans, climate emergency savings accounts, climate-smart agriculture loans, and bundled parametric insurance. These products will be designed specifically to help households prepare for shocks and recover from them. They will be part of BURO’s ongoing business transformation endeavor to future-proof the organization.

BURO will enhance customer climate resilience in two phases. Phase 1 (6–12 months) will focus on repurposing and foundational rejigs, while phase 2 (1–2 years) will develop and scale new products and partnerships.

BURO believes that this approach will enable it to significantly enhance its impact by providing its clients with faster access to more flexible funds. This is expected to result in steadier incomes and fewer distress sales among clients, alongside a more resilient portfolio, clearer risk visibility, and even higher customer loyalty.

Case 2: MSC’s engagement with four Indian MFIs on climate-smart agriculture products

As part of an IDH-supported project, MSC identified climate-smart agriculture financing opportunities for IFSPs in India based on an analysis of their current product portfolio.

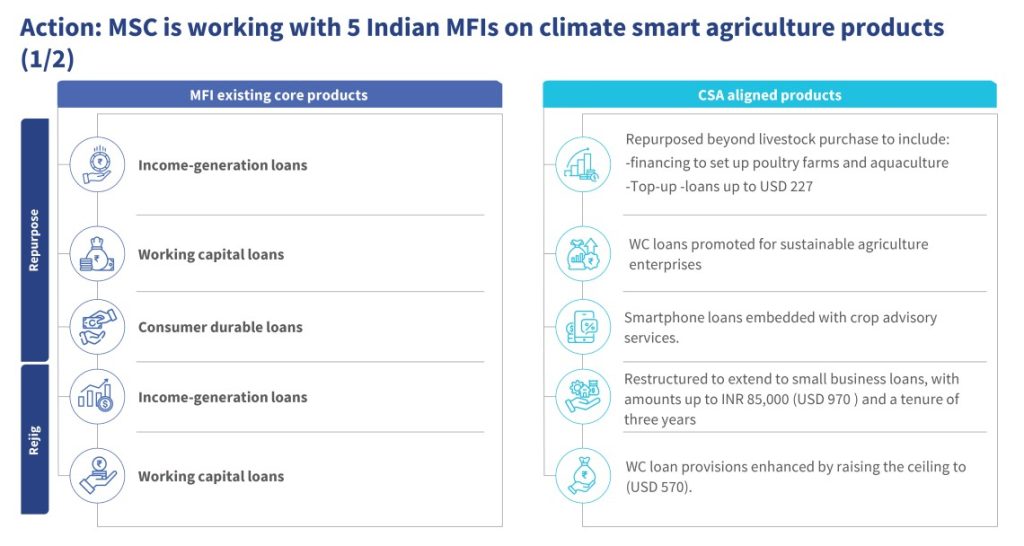

Currently, MSC is working with four MFIs in India on an ISEF-supported project to repurpose, rejig, and reinvent their product suite to support climate-smart agriculture (CSA).

Repurpose: This component seeks to reorient the IFSPs’ existing loans toward CSA. Income-generation loans are now being extended beyond the traditional livestock to finance poultry farms and aquaculture, with additional rapid top-ups to respond to seasonal needs. As part of this component, working-capital loans will be explicitly promoted for sustainable agriculture enterprises. In addition, the IFSP’s consumer durable credit products will include loans for smartphones bundled with crop-advisory services, which would turn the handset into a decision-making tool on the farm.

Rejig: This component seeks to tune product terms to fit CSA growth. Income-generation loans are being restructured into small-business loans, with larger ticket sizes and increased tenors of up to three years to support larger investments. As part of the rejig component, working capital limits are increased to provide farmers with more flexibility to purchase resilient inputs when they are needed most.

These small yet precise changes unlock climate value through faster adoption, better timing, and smarter decisions, yet keep underwriting and operations familiar for staff and clients.

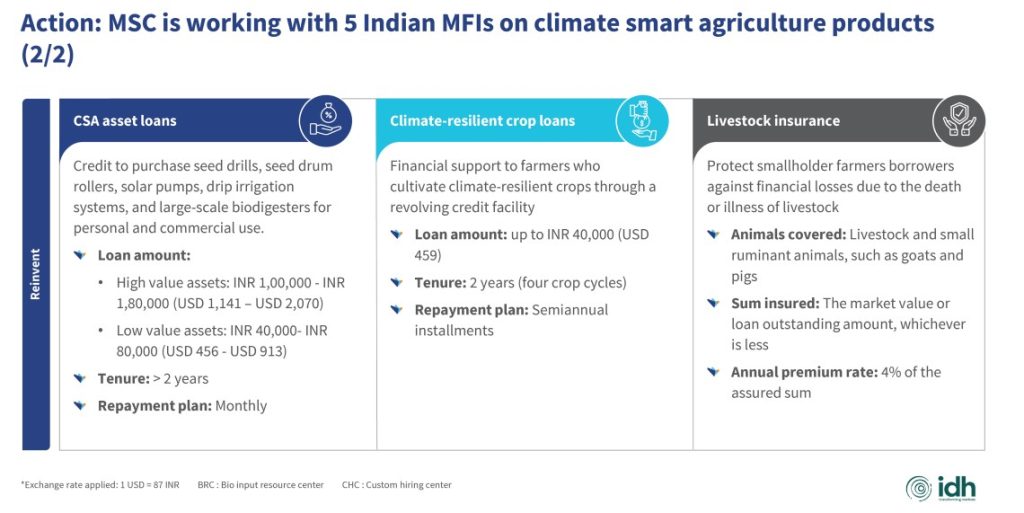

Reinventing products is, of course, the most challenging and requires careful human-centered design and thorough pilot testing. We are focusing on three climate-smart agriculture loans under this part of the 3R strategy.

- CSA asset loans will provide credit for on-farm technologies that boost resilience and efficiency, with increased loan amounts depending on the assets being acquired. These increased loan sizes will be matched by increased tenures of two to three years and will be repaid via monthly instalments.

- Climate-resilient crop loans will offer a revolving credit facility that backs farmers who grow these crops. These relatively small loans will be offered with a tenure of two years, repayable in semi-annual instalments to coincide with crop cycles.

- Livestock insurance will provide protection against financial loss from the death or illness of livestock, such as goats and pigs. The sum insured will be the lower of the market value or the loan outstanding, for a premium of just 4% of the assured sum.

These reinvented products are more complex and riskier than those that are simply repurposed or rejigged. As a result, the MFIs are likely to seek blended finance to de-risk their delivery. Nonetheless, together, these “reinvent” products finance the hardware and working cycles, while providing the risk transfer that farmers need to adapt. Most importantly, they slot neatly alongside the MFIs’ existing microcredit operations.

The products also offer phased, seasonal, purpose-tied loans for agriculture with repayment schedules that match cash cycles. These are further strengthened by the addition of exception rules for disaster periods, such as automatic grace periods, remote guarantors or KYC, and branch-level liquidity buffers, so staff do not ration financing in the face of climate events.

The way ahead

The 3R framework aligns directly with global guidance on climate-resilient financial inclusion and climate-smart agriculture. It offers MFIs and banks a practical pathway to originate millions of small, standardized, adaptation-linked receivables that private capital can finance. Poor households worldwide are already being compelled to adapt to the effects of climate change. In response, IFSPs should adopt the 3Rs framework to guide their product response to support their clients’ adaptation and resilience.

Over the past 50 years, we have built a financial services infrastructure designed to reach and serve these vulnerable communities. We should use climate funds to de-risk their operations, repurpose, rejig, and reinvent their products, and crowd in the USD 1.5 trillion capital that this remarkable infrastructure manages. We simply cannot afford to miss this opportunity.