Micro and small enterprises: Will the pandemic put an end to their business?

by Nitish Narain, Abhishek Anand, Surbhi Sood and Shobhit Mishra

Apr 15, 2020

7 min

This blog looks at the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on micro and small enterprises (MSEs) across low- and middle-income countries, which are particularly vulnerable to shocks. Our research insights will help policymakers and financial institutions support the recovery and rebuilding of the MSME sector in the wake of the disease.

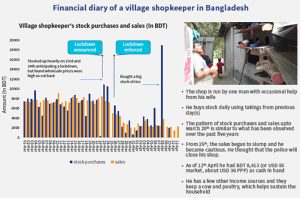

Mohammad Islam runs a small grocery shop in Dhaka. Like many, he was aware of the COVID-19 crisis unfolding in China. Yet he could never anticipate the pandemic would hit him and his business so fast, and so hard. Since the Bangladesh government announced a national lockdown, Mohammad Islam has seen his revenues decline by 20%. Thankfully, his business falls in the “essential services” category. He is allowed to open his shop albeit for limited hours. However, his stock levels have been depleting and supplies remain unpredictable. He thinks small traders like him, particularly those whose businesses are shut completely, will suffer the most. These businesses are also least likely to receive support from anyone, including the government. “The government plans packages for large businesses and the poor—nobody thinks about us”, ruminates another small trader in Nagerhat, Bangladesh.

Policy measures will be needed to minimize the impact on micro and small enterprises (MSEs) like those managed by Mohammad Islam. This case is symptomatic of the position of MSEs across low- and middle-income countries. These businesses are more vulnerable because they have limited cash reserves. And of course, business cash flows are fungible with household cash flows and vice-versa. They have rents to pay, typically make a significant proportion of sales on credit, and rarely use formal financial products.

Since the pandemic, the realization of sales proceeds on credit has crashed even as revenue continues on a rapid, downward trajectory. This will have an impact on the survival of MSEs in the short to medium term. Such businesses are un-registered, which makes it even more difficult for policymakers to target them effectively for support.

In this context, MSC kick-started a three-stage research exercise across eight countries in Asia and Africa to understand the nature and extent of the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on micro and small enterprises. The research will gather evidence to inform policymakers to devise short–term, medium-term, and long-term support for such micro and small enterprises. The research will also inform MSE-focused financial institutions and their investors on remodeling business strategies to address the evolving needs of such enterprises better.

The early evidence from our research provides important insights that policy makers and other key stakeholders should consider as we prepare for recovery and rebuilding.

Most micro and small entrepreneurs believe that it will take at least another three months to normalize businesses, once the pandemic has been contained. Businesses that had purchased inventory immediately before the lockdown are the most affected.

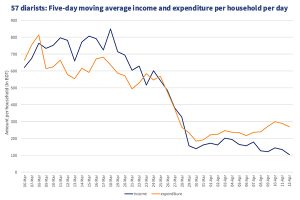

Data from 57 of Stuart Rutherford’s financial diarists, all of whom are from low- and middle-income households, in Hrishipara in Bangladesh, highlights a sharp decline in income and expenses immediately after the national lockdown. The Hrishipara Financial Diaries provide invaluable granular details on the lives of the poor and the impact of COVID-19. They show that income per household per day has currently dropped to BDT 100 (USD 1.18). Their expenditure has consistently been larger than income during the period, suggesting that household reserves are being eroded steadily.

This decline in economic activity and erosion of savings at the household level is likely to reduce demand, which will further have an impact on micro and small businesses that serve these low- and middle-income households.

Household Income and Expenditure graph

The story is similar in Indonesia, where the availability of credit from suppliers has started to dwindle, affecting the liquidity position of micro and small enterprises. “Before the Corona pandemic, my wholesalers allowed me to buy goods on credit. The pandemic has resulted in scarcity, and the wholesaler has stopped extending credit for products that are in high demand, such as vitamins, paracetamol, antibiotics, and flu medicine”, said a small pharmacy owner in urban Jakarta. He went on to add that wholesalers accept nothing but cash payment for these products. Restrictions have also been placed on the volume that can be stocked to avoid hoarding. “For other products that are not so much in demand, the wholesaler is still willing to give credit for one month”, he says.

Financial Diary of a village shopkeeper in Bangladesh

While credit from wholesalers is drying up, MSEs are finding it difficult to realize cash from credit sales that they have made to their long-standing customers. “I give items on credit to many of my repeat customers—most of whom are daily wage earners. These customers used to pay me in cash on a weekly or monthly basis. However, because of the lock-down, people are not allowed to move freely and the amount owed to me is mounting. I am now worried whether I will ever realize my dues,” rued a small retail trader of tobacco and bakery products in India. Despite the challenges, some grocery retailers in India feel obliged to provide credit to their existing customer base, further adding to their liquidity crunch.

Given the evidence so far, a comprehensive policy framework to support micro and small enterprises will be essential. Many governments have responded with specific measures, such as a moratorium on the repayment of existing loans by MSMEs. However, these are at best, short-term solutions. A more nuanced approach will be needed going forward. Otherwise, the survival of most MSEs will be open to question.

A policy framework to accelerate the recovery of micro and small businesses should achieve the following objectives:

- Address the immediate shock in cash flow

The liquidity crunch has severely affected microenterprises, particularly those managed by low-income families. They need immediate cash assistance to manage short-term cash flows. A cash transfer spread over three to six months will help these enterprises address the immediate shock in their cash flow. The volume of such cash transfer should cover the basic monthly expenses of the household.

- Support enterprises to reduce expenses

Governments may consider offering direct subsidy to micro and small businesses through a waiver of utility bills. However, such a waiver should be tier-based to prevent wastage and overuse. “Electricity and water should be available for free for up to three to six months so that we can cover our losses. This might help us a little. Otherwise this year we do not know what we will earn and what we will save,” said a manufacturer of printing machinery in India.

- Take proactive measures to boost sales and augment supply

Even amid the national lockdown in several countries, businesses classified as “essential services” are allowed to function with certain restrictions. The government, particularly local authorities, should work with such enterprises to ensure they can sell their goods without any fear of forced closure of shops. Our research shows that the police response across and within several countries is variable—some allow stores to remain open, while others insist that they shut.

Also, local authorities should permit and promote enterprises that offer home delivery services to support their sales.

Policy-makers should also focus on improving supplies. The value chain that gets raw materials and goods to MSEs must function effectively. Evidence from grocery stores in our research sample from India suggests that while the supply of food grains is robust, the supply of packaged food and other non-food essentials, such as toiletries and personal hygiene products is limited. This may be because the manufacture of such products has stalled or due to the closure of state borders, which restricts the movement of goods.

- Promote the adoption of digital payments and the use of social media

Many entrepreneurs, especially in India, have been taking orders over WhatsApp. Customers enter the items they want or send a picture of their hand-written shopping lists. Digital payment options like Paytm and GooglePay facilitate home delivery options. The government should promote social media and digital payments as it helps social distancing even as business can be carried out. Governments may partner with private sector players, such as digital payments firms and social media platforms to enhance both personal hygiene communication and the development of the digital ecosystem.

- Increase access to credit

The moratorium on existing loans to MSMEs, where allowed, will help address immediate challenges in liquidity. Nonetheless, those businesses that are allowed to operate during the lockdown will be able to repay their existing loans. However, they will need assurance that they will get additional credit once they complete their repayments. Therefore, policymakers and financial service providers need a nuanced, rather than a blanket approach.

Digital lenders that offer working capital assistance based on cash flows may be positioned better to offer instant credit delivered remotely. Any repayment moratorium on loans to enterprises should be based on the recovery cycle and the cash flows as they build-up. Similarly, a moratorium for those entrepreneurs who take loans after the initiation of lockdown should be reconsidered, so that lenders have the confidence to advance credit to businesses that are still functioning. This will help maintain credit discipline while maintaining some business revenue and liquidity for financial institutions offering loans to such enterprises.

Financial institutions are also part of a value chain. Unless those that extend wholesale credit to MSEs, such as microfinance institutions, get similar repayment moratorium, the liquidity position of frontline financial institutions will be affected. Hence, repayments have to be reworked across the credit supply chain.

The government should also use the opportunity to boost efforts to formalize micro and small businesses to deliver some of these policy outcomes effectively. This may require confidence-building measures among the micro and small enterprises and for MSEs to realize the benefits of formalization. The question remains — what are these and how do we communicate them effectively?

Written by

Nitish Narain

Specialist

Abhishek Anand

Senior Partner

Surbhi Sood

Senior Manager

by

by  Apr 15, 2020

Apr 15, 2020 7 min

7 min

Leave comments