Finance is the key (often missing) ingredient in locally-led adaptation

by Graham Wright, Anant Jayant Natu and Partha Ghosh

by Graham Wright, Anant Jayant Natu and Partha Ghosh Feb 5, 2024

Feb 5, 2024 5 min

5 min

This blog explores the crucial role of finance in locally-led adaptation to climate change. It emphasizes the subnational jurisdictions’ role in locally-led adaptation as they provide the resources and support required for informed and tailored climate change investments. The blog highlights the absence of ways to finance locally-led adaptation in available literature despite a need for resources. It introduces seven essential principles to finance locally-led adaptation effectively and underscores the private sector’s potential role, which is often overlooked. It highlights blended finance as a promising solution that combines public and private investments.

UNEP estimates adaptation costs for developing countries will increase to USD 160-340 billion annually by 2030 and USD 315-565 billion by 2050 (UNEP, 2022). This is five to seven times higher than the USD 49 billion of global adaptation flows in 2019-2020.

Climate risk primarily emerges at the local level. Effective adaptation measures tailored to local needs and priorities have proven successful when implemented close to the affected communities. This success is achieved through a combination of nationally planned and community-based autonomous adaptation (Quevedo et al. 2019). Therefore, it makes sense that subnational jurisdictions that are directly impacted should take responsibility for adaptation. National governments and public funds provide the regulatory and policy environment, oversight, and finance for the initiatives with participation from philanthropies and the private sector. At the same time, subnational levels of the government design, plan, and implement adaptation measures alongside affected communities— an approach known as locally-led adaptation.

This approach resonates with two core principles from the general decentralization theory (see figure below):

- Subsidiarity: If services can be provided at multiple levels, they should be entrusted to the level of the most local government. This level should align with the region that benefits from those services.

- Correspondence: A governing body’s jurisdictional boundaries that provide a service should match the region that benefits from that service (Martinez-Vazquez 2021).

Financial resources for effective locally-led adaptation

Effective locally-led adaptation strategies prioritize the local communities’ decision-making authority to address climate change. They also provide the resources and support needed for informed climate adaptation investments. However, many adaptation strategies remain top-down and are typically managed by donors, major intermediaries, and central governments. A study by WRI revealed that only around 6% of 374 community-focused interventions incorporated local-led components, such as local decision-making. This highlights how we must urgently address the barriers to locally-led adaptation.

A notable exception is IIED’s “The good climate finance guide for investing in locally-led adaptation.” However, finance remains the key missing ingredient in successful adaptation. Insufficient financing hinders the scale-up of localized solutions, capacity building, and technology adoption. It harms project sustainability and risks unequal distribution of adaptive capabilities across communities.

Several challenges hinder the shift toward financing locally-led adaptation. These include complex funding distribution mechanisms, unclear procedures for planning, consultation, and decision-making, inconsistent and hard-to-access data on budgets and international aid, and limited resources. These challenges prevent governments from examining if local or global financing supports local adaptation. However, broad principles have already been articulated.

Seven essential principles to effectively finance locally-led adaptation

Patel et al., 2020 highlight seven principles to finance adaptation effectively. Unsurprisingly, the first two reflect the principles outlined by the Asian Development Bank, 2023:

- Subsidiarity: Decisions should be made as close as possible to those most impacted. This ensures designs are tailored to specific areas, local relevance, and enhanced accountability toward the most vulnerable.

- Convergence: No single action can address all climate-related risks. However, convergence is under-documented, which makes its assessment challenging.

- Robust decision-making: Local stakeholders need to understand climate risks and uncertainties thoroughly. This ensures both current climate risks and generational insights inform their choices.

- Patient and predictable: Long-term perspectives in climate finance are vital.

- Flexibility: Adaptive programming is essential, given the unpredictability of climate change.

- Risk-taking: Early investments in local institutions unfamiliar with the management of climate finance are essential. But it should focus on data, technology, and capacity building from the outset.

- Predictability: Local stakeholders should be able to rely on consistent or future financial support (Coger et al., 2021).

However, the private sector’s role has been largely overlooked

The private sector has significant potential to meet Africa’s climate finance needs. However, nationally-determined contributions (NDCs) from governments rarely discuss its role. Public funding alone will not be sufficient, given the magnitude of investments needed and current and future constraints on public domestic resources in the continent. However, most current climate financing in Africa is from public actors with limited finance from private players. It accounts for up to 87%, which amounts to USD 20 billion with limited finance from private players (Guzman et al 2022).

IIED’s highly regarded primer on locally-led adaptation financing has few examples of private-sector funding for LLA. WRI’s recent paper concluded that “with supportive financial structures in place, the private sector can scale up investment in climate change adaptation—and in fact could play an essential role in closing the substantial adaptation finance gap” (WRI, 2023).

Research indicates that Kenya has made significant efforts to prepare itself for climate finance, as evidenced by its climate-focused policies, laws, and institutions. However, the country has room to improve, especially in how well it acknowledges and bolsters the private sector’s role in this arena (Kiremu et al., 2021). The World Bank’s 2022 Climate and Country Development report for Bangladesh that LLA can help generate financing for MSMEs for climate resilience.

International and national public sector funds alone will fail to provide the enormous sums of money required to support adaptation and build vulnerable communities’ resilience worldwide. For example, the African Development Bank notes that “to close Africa’s climate financing gap by 2030, approximately USD 213.4 billion will need to be mobilized annually from the private sector to complement constrained public resources”.

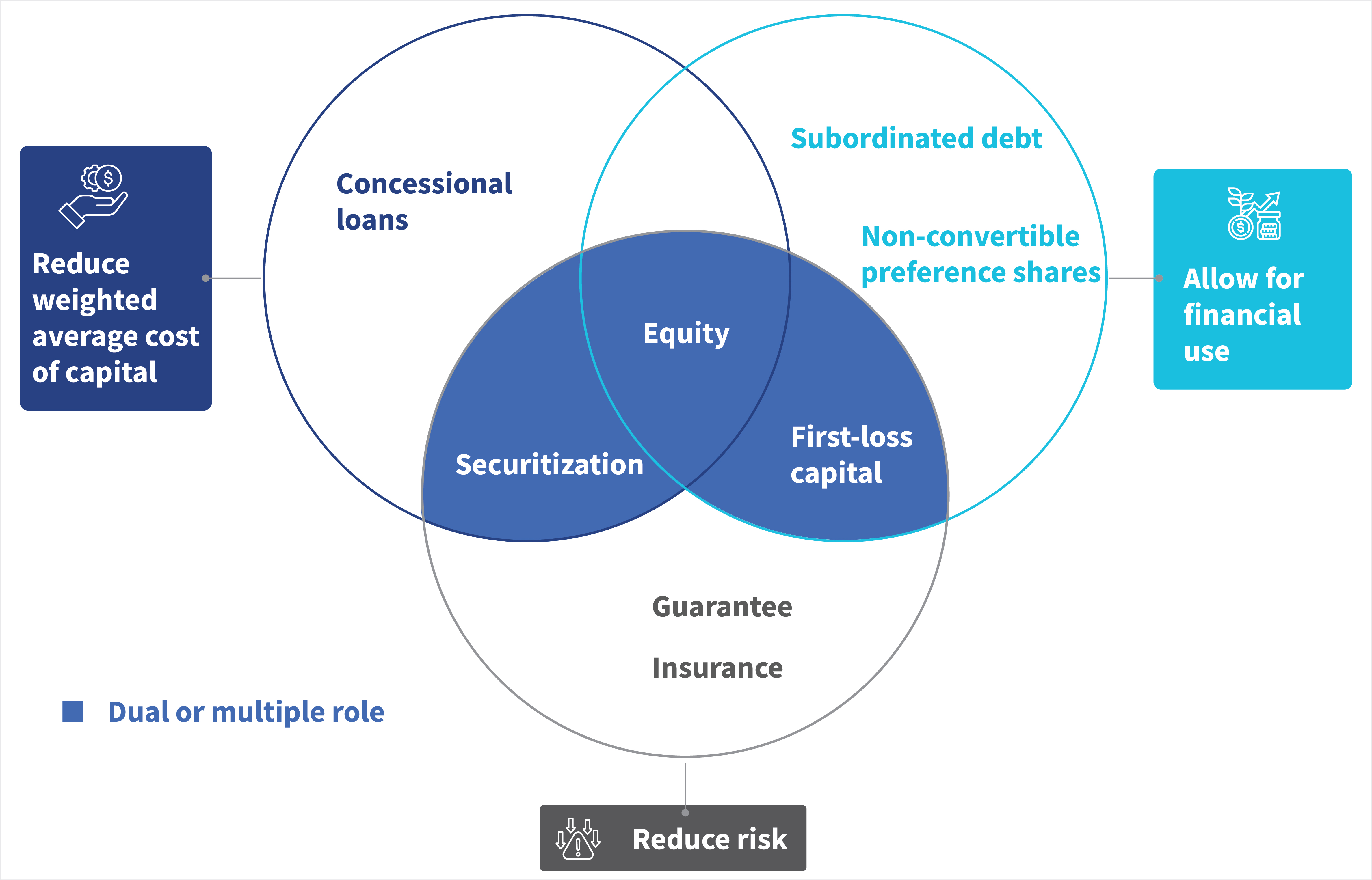

Blended finance combines public and private sector investments. It offers a promising avenue to reduce risk and the weighted cost of capital. Additionally, it allows the use of capital to catalyze innovation and market transformation at scale. The public sector can offer initial risk protection through investments, equity capital, or improved credit conditions. It includes national governments and multilateral development banks, such as the (EIB). If development partners and multilateral banks focus on equity rather than debt, they can prevent an increase in developing nations’ debt load (IMF’s Bo Li at EIB Group Forum 2023).

The private sector holds the most significant amount of capital. We must align this capital with climate and sustainable development objectives. Although public finance is smaller in scale, it remains vital since policymakers can control it directly. Additionally, it funds public goods and services that the private sector may not support. When used correctly, public finance can boost private investment as it can promote markets, drive innovation, and minimize risks (Amerasinghe et al. 2019).

For example, a profound disconnect often occurs between financial services and the communities most vulnerable to climate change. These communities are often poor and remote, so financial service providers cannot serve them profitably. Moreover, these communities often depend on smallholder agriculture and are thus subject to covariant risk—a problem that climate change amplifies. This makes them less attractive to institutions that offer credit or insurance services. The digital revolution and the advent of digital financial services could play an important role to address these challenges. Nonetheless, public and philanthropic funds will likely be needed to manage risk through first-loss guarantees alongside other innovative approaches.

The implementation of effective risk-sharing mechanisms requires a thorough understanding of the specific risks involved in a project and potential investors’ risk appetite. Blended finance arrangements can mobilize significant private capital to support locally-led adaptation at scale through the judicious application of these tools.

Read the CIFAR Alliance locally-led adaptation whitepaper for a closer look at LLA and its challenges.

Written by

Graham Wright

Group Managing Director

Anant Jayant Natu

Associate Partner

Leave comments