Gender-intelligent banking (part 2): Small changes, big wins: How small changes by FSPs can result in big wins

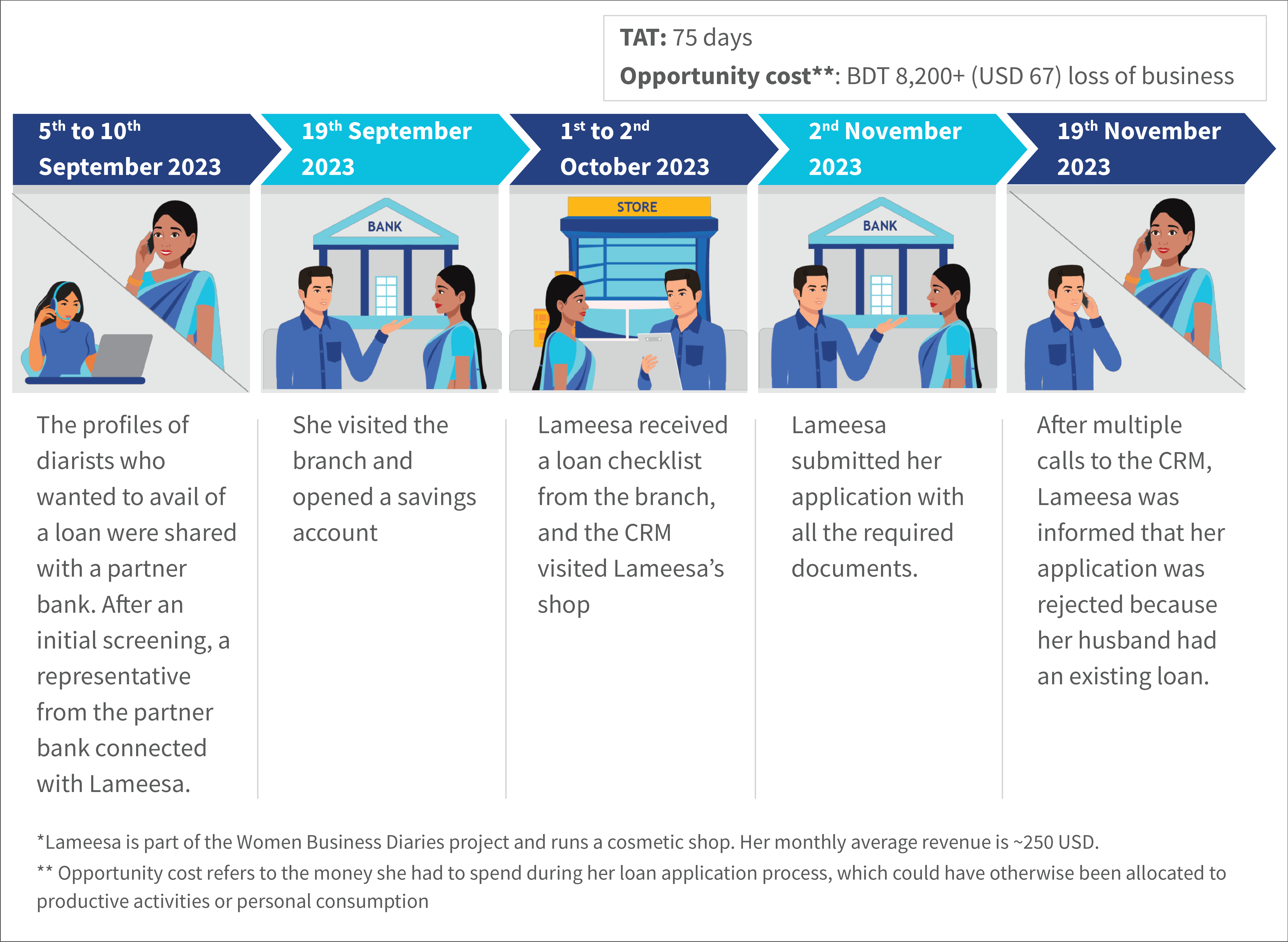

Lameesa Akter, a successful cosmetics shop owner in Kotuali, Rangpur, applied for a BDT 5,00,000 (USD 4,180) loan at a bank. She had to spend two months running around the bank, which led to significant opportunity costs and a direct cost of BDT 5,000 (USD 42) in upfront expenses. However, she soon learned her loan application was invalid, and hence the loan was denied.

Lameesa’s story is not unique, as countless women in Bangladesh like her struggle to access financial products tailored to their specific needs and context. In the first part of this two-part blog series, we discussed the challenges practitioners face when they create gender-intentional products and services.

This blog highlights two insights from our work that our partner banks have used to address these challenges. These efforts have translated into small yet impactful product and channel design adjustments to improve women’s access to financial products. For more insights, see Insights to innovations: Designing financial services for women entrepreneurs.

- Small ticket-size savings

Many banks in Bangladesh impose minimum deposit requirements, which range from BDT 10,000 (USD 84) to BDT 50,000 (USD 420). This is a significant barrier for women. Additionally, banks lack flexibility regarding savings product tenures and partial withdrawals.

Only 32% of women in our study saved at a bank. Many save informally at home or through other formal channels, such as microfinance institutions (MFIs), deposit pension scheme (DPS), and samitis, as these allow more flexible saving plans.

The table above presents the median amount saved by those who deposit a certain amount regularly through a savings instrument. It shows that this amount is the highest for savings in bank accounts, followed by DPS and MFI deposits. This implies that banks command the savers’ trust, but people save at banks only when they have substantial money to deposit in their accounts. Banks can introduce more flexibility in the amount that can customers can deposit and replicate a flexible model to attract savings from women entrepreneurs, which would help build their savings portfolio. Such a product would allow women who have just launched their businesses to gain banking experience and help banks onboard future credit-ready customers.

Mutual Trust Bank (MTB), one of our partner banks, built on these insights and designed a unique small savings product that specifically targets women entrepreneurs. Through a bundled, secured overdraft (SOD) facility in the accounts, MTB has enabled women to avail of low-cost, short-term, and readily accessible credit based on their savings accounts. The loan eligibility and amount would depend on their savings, which would also act as a nudge for these women entrepreneurs to save consistently.

- Last-mile outreach through the digitization of delivery channels

The complex and extensive application paperwork involved in loan processing can be overwhelming and may deter many potential applicants. The lengthy turnaround time for loan processing further increases opportunity costs, which makes it difficult for women to dedicate the time needed to complete the process. Many diarists mention bank officials offer little support when they handle the diarists’ queries, which adversely affects their trust and confidence in the banks.

Women entrepreneurs also reported that multiple visits to the bank branch for loan applications adversely affect their business and personal lives and pose opportunity costs. Per our mapped credit journeys, they incur as much as BDT 6,000 (USD 50) in direct costs and at least five days of revenue loss as opportunity costs. For some, the long turnaround time banks take to process applications can be even more costly, as seen through the customer journey of Lameesa, the Women Business Diaries Project diarist whom we met at the start of this blog.

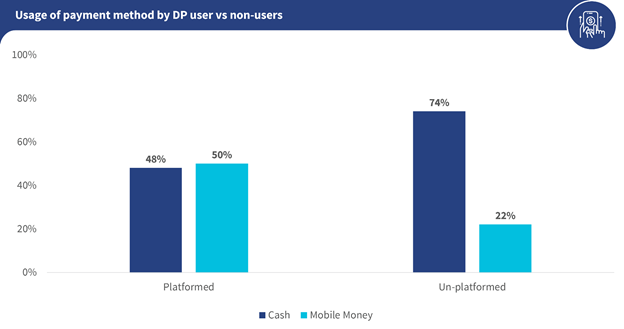

Alternate service delivery channels, such as mobile banking and digital application systems, can emerge as a practical solution. These can help reach women entrepreneurs in remote areas and ensure that applications are accepted only when required documents are submitted, which increases the likelihood of conversion of these leads. Our research also finds that most women are comfortable using digital interfaces in their daily lives, and 87% use their phones for mobile payments.

A digital loan application and tracking system will potentially solve these issues for female applicants and enhance their accessibility to bank loans. Insights from the project have facilitated Bank Asia, another partner bank, to create an online lead generation and loan application system, which uses digital channels for credit lead sourcing and application.

Making gender-intelligent financial services a habit

MTB and Bank Asia’s gender-intelligent product design exemplifies two critical pillars of gender-intentional banking: Data-driven decision-making and gender-focused business strategies. A gender-intelligent approach ensures that products and services are more accessible to women and have a greater potential for long-term adoption.

Through the pilot of its goal-based savings product, MTB seeks to onboard at least 500 new clients in the first year, with each client expected to save between BDT 25,000 (USD 210) and BDT 50,000 (USD 420) annually. This would result in a total savings portfolio of approximately BDT 2.5 million (USD 21,000) within the first year. Meanwhile, Bank Asia plans to extend credit to 1,000 additional clients through its pilot of a new digital lead generation and loan application system, with a minimum loan size of BDT 200,000 (USD 1,675). This would enable the disbursement of an additional BDT 200 million (USD 1.68 million) in its first year.

Financial institutions can create a lasting cultural shift if they embed gender intentionality across their governance, operations, and impact measurement. While MTB and Bank Asia have taken the initial steps, they are well-positioned to harness the significant business opportunities that emerge from serving female customers, such as Lameesa, and so many others like her.