Blog

Community of Practice: Creation of local knowledge networks through innovative tech solutions to support women-led businesses’ expansion

Background

“I have just started my business and do not know what credit is and how I can use it to benefit my business. I am too afraid to ask anyone and do not know where to go,” rues Sita, a budding women entrepreneur from Gujarat. Her situation highlights the critical need for stakeholders to encourage and integrate peer-based learning and growth into the ambitions of women-led businesses (WLBs) like hers.

For any business, knowledge is as essential as financial capital. It fosters shared learning experiences, particularly among WLBs, and serves as a catalyst in their growth. Today, more than 15.7 million WLBs in India contribute significantly to the economy. They employ 27 million+ people. Despite their impact, they grapple with many challenges rooted primarily in the lack of knowledge of business aspects, such as bookkeeping and supply chain management. The unorganized sector also struggles with information asymmetry.

The potential of Communities of Practice (CoPs) becomes evident in such a dynamic landscape. They serve as a valuable source of shared knowledge to foster empowerment and encourage collective wisdom within communities.

A CoP is a collaborative network where individuals bond over a shared interest or field and engage in collective learning and expertise development. WLBs exchange knowledge, innovate, and solve problems through regular interaction. They also enhance their professional practices and personal growth.

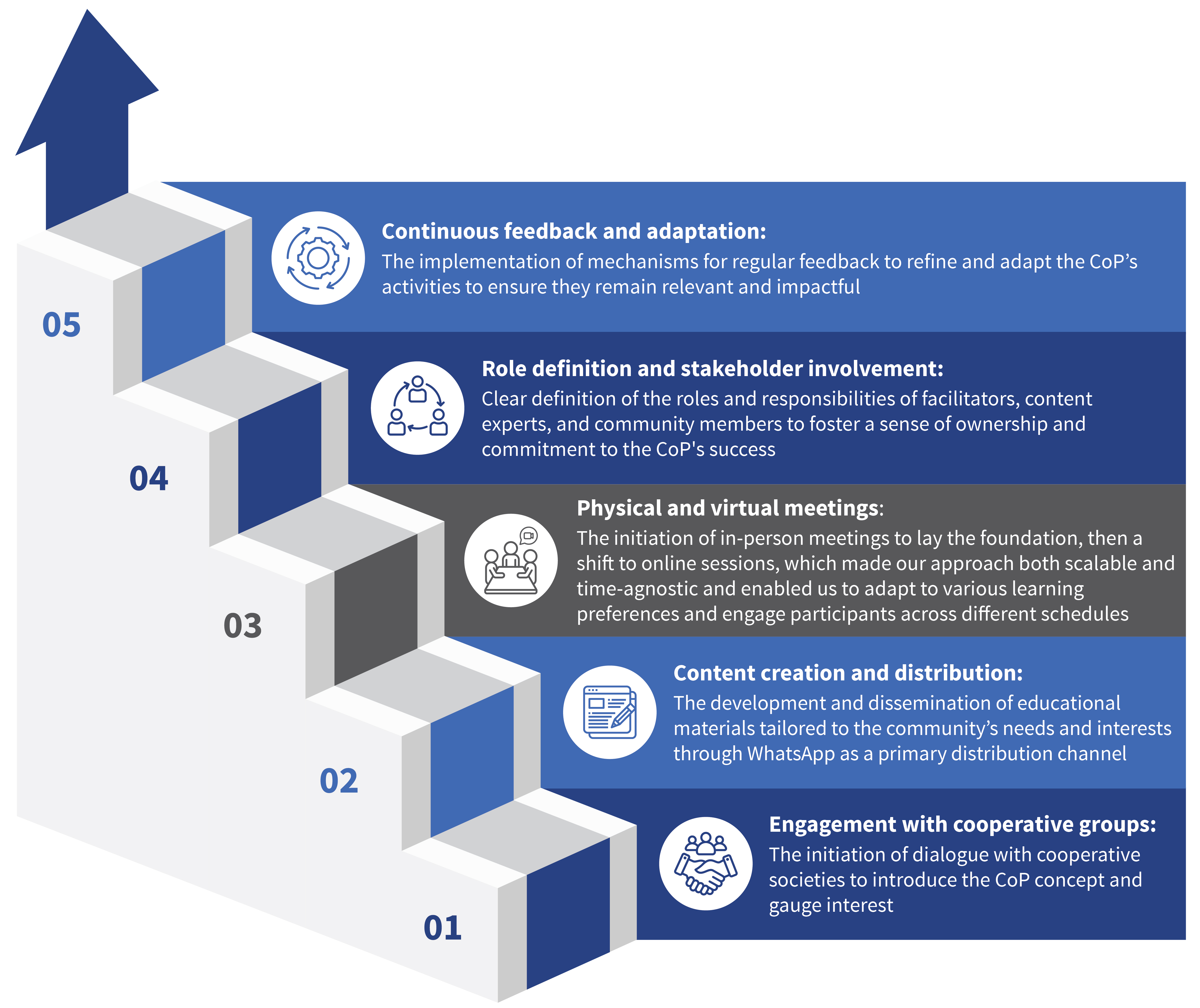

Figure 1: Steps involved in the set up of our CoP in Gujarat

CoPs are more than just groups of people with similar interests. They are dynamic gatherings where people learn, share, and grow collectively—enabled by simple technology. A CoP is built on a shared domain of interest. A belief that learning is a social activity rooted in WLBs’ interactions and experiences drives community building. It fosters identity and focus alongside a committed community that learns and shares knowledge together. These elements create a rich environment for WLBs to develop expertise and solve problems collectively.

CoPs emerged as a lifeline in this context. They provide a supportive network to share strategies, solutions, and successes. MSC recognized that these CoPs were bound by the pursuit to deepen their expertise and solve complex challenges collaboratively, unlike informal networks or work teams. They transcend institutional and geographical boundaries.

How we build a CoP

We started our CoP in Gujarat with the SEWA Federation’s WLBs to address the awareness-related challenges around entrepreneurship. A recognition that digital platforms could demolish barriers, connect remote areas, and foster a spirit of collaboration and innovation drove this mission. We could create a scalable and accessible model for collective growth and learning through technology. Our choice to use WhatsApp was strategic. Its universal appeal, high uptake, usage, and ease of use made it an ideal platform. We shared educational content through WhatsApp, facilitated discussions, and built a strong sense of community. This approach allowed us to reach WLBs where they were most comfortable, and we made learning and engagement natural, effective, and self-paced.

A CoP’s establishment in any geography follows a meticulous process. It begins with the identification of stakeholders and the assessment of local needs. In Gujarat, it involved five steps that are illustrated in the infographic below:

How we sustained the process

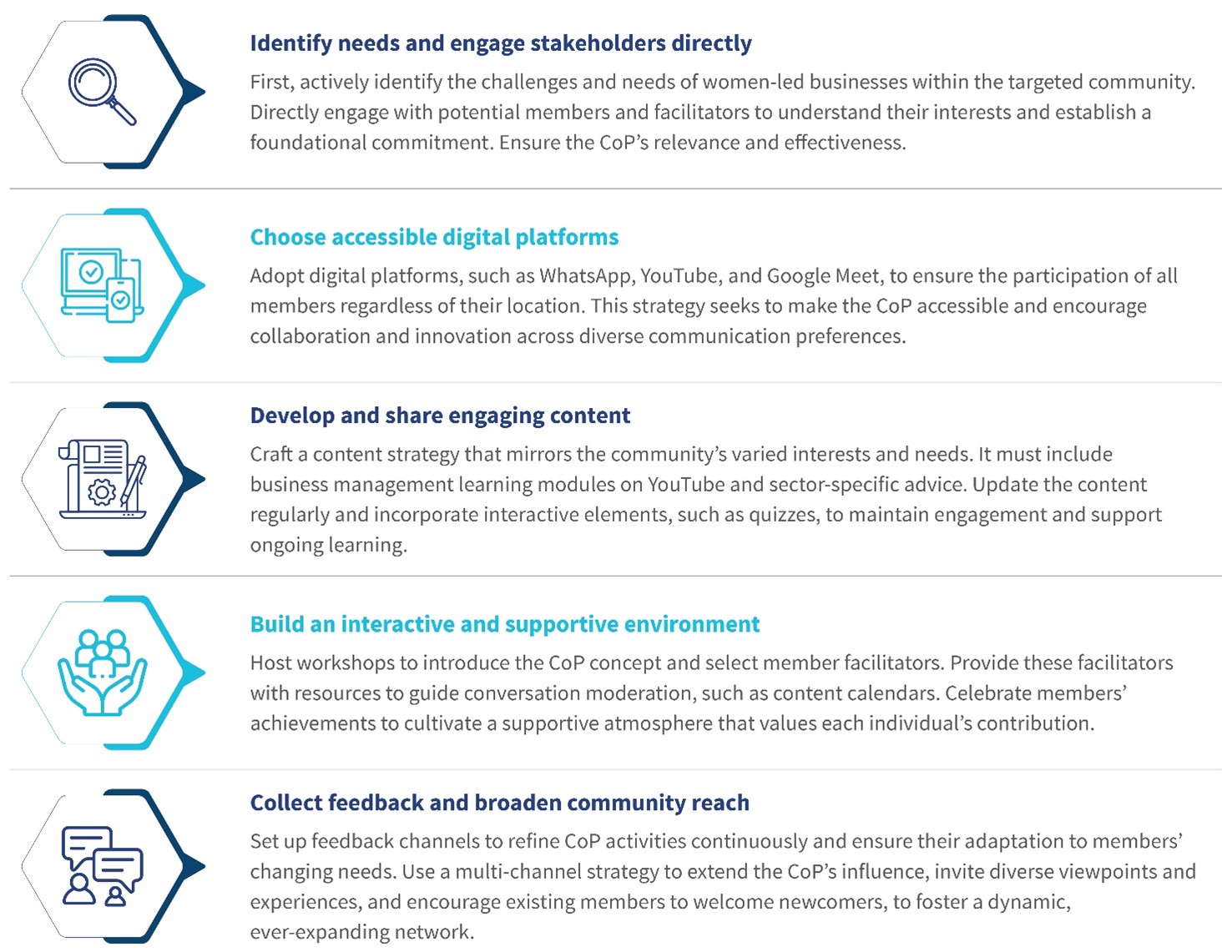

In our latest journey with CoPs on WhatsApp, we crafted a tailored, bottom-up approach that aligns with the community WLBs’ specific interests and needs. We have listed strategies that enabled us to keep these groups active, engaged, and continuously learning below:

- Moderation and guidance: Facilitators in our CoPs, who were also WLBs, were crucial to uphold the focus and respectfulness of discussions. We conducted on-ground workshops to enhance their effectiveness and set the context. We identified WLBs who could lead these conversations during these workshops. We created content calendars for the facilitators to simplify the moderation process. This strategy ensured our interactions stayed meaningful, engaging, and aligned with our community’s inclusive values.

- Regular content updates: We prioritized the creation of learning modules on YouTube as we recognized varied interests and needs within our community. We ensured the content was relevant and timely. Our offerings included a broad spectrum of materials—from instructional videos and hands-on advice to best practices across various areas, such as credit management, insurance, social media marketing, and digital payment processes. We also developed tailored content on topics to cater to our community’s unique sectors, such as animal husbandry for dairy cooperatives and stitching techniques for handicraft cooperatives. This strategic approach to content creation ensured our learning modules were informative and directly applicable to the varied needs of our community WLBs.

- Interactive activities: We launched interactive activities that merged learning with fun as part of our strategy to deepen member engagement and knowledge. We introduced creative challenges to spark innovation, quizzes to solidify knowledge, and gamification methods, such as points and badges, to create a competitive yet enjoyable learning environment. Calls to action kept the WLBs engaged, led them to the next learning experience, and ensured ongoing participation. We expanded viewpoints through discussions on various topics and made each interaction an insightful moment. This approach made learning enjoyable, promoted critical thinking and collaborative learning, and fostered a dynamic educational community environment.

- Bridging the digital skills gap: A lack of digital skills among WLBs was a significant and often overlooked barrier that prevented full digital engagement. Our workshops thus sought to improve digital skills. These covered everything from basic smartphone usage to advanced online safety practices and empowered WLBs to navigate digital spaces more confidently.

- Member spotlights: The recognition and celebration of individual achievements and contributions were central to our community-building strategy. We highlighted our WLBs’ successes, acknowledged their efforts, and reinforced their value within the community, which enhanced the collective sense of belonging and mutual appreciation. We could also see a positive uptake in the group’s interactions after the recognition activity.

- Feedback loops: The establishment of effective feedback channels was integral to our adaptive strategy. It allowed the WLBs to voice their opinions and suggestions about the CoP’s activities. We went on the field and got in-person feedback from different sets of women to implement it in our CoP activities. This invaluable input enabled us to refine our approach continually and ensure the community’s evolution in alignment with the WLBs’ shifting needs and interests.

- Expanding our reach: We embraced a multichannel strategy and extended our engagement to include WhatsApp, YouTube, and Google Meet, among other technologies, to connect our CoPs effectively. This comprehensive approach ensured quality interactions across various platforms that would cater to the WLBs’ diverse preferences. It facilitated active participation and encouraged them to invite others into our community.

Figure 2: Standard guidelines to form a CoP

The journey from here

As the initiative looks to the future, its experiences with SEWA in Gujarat offer a blueprint to expand CoPs. This experience promises to revolutionize how women entrepreneurs connect, learn, and grow together. Yet, a sustainable structure requires key stakeholders’ engagement and clearly defined roles for facilitators, WLBs, and experts. Regular interactions, shared goals, and a commitment to mutual growth form the bedrock of a successful CoP.

An examination of CoPs across different sectors and countries reveals diverse applications and outcomes. The transformative power of CoPs to foster knowledge sharing and empowerment is evident in MSC’s multicountry initiatives across Vietnam and Nepal.

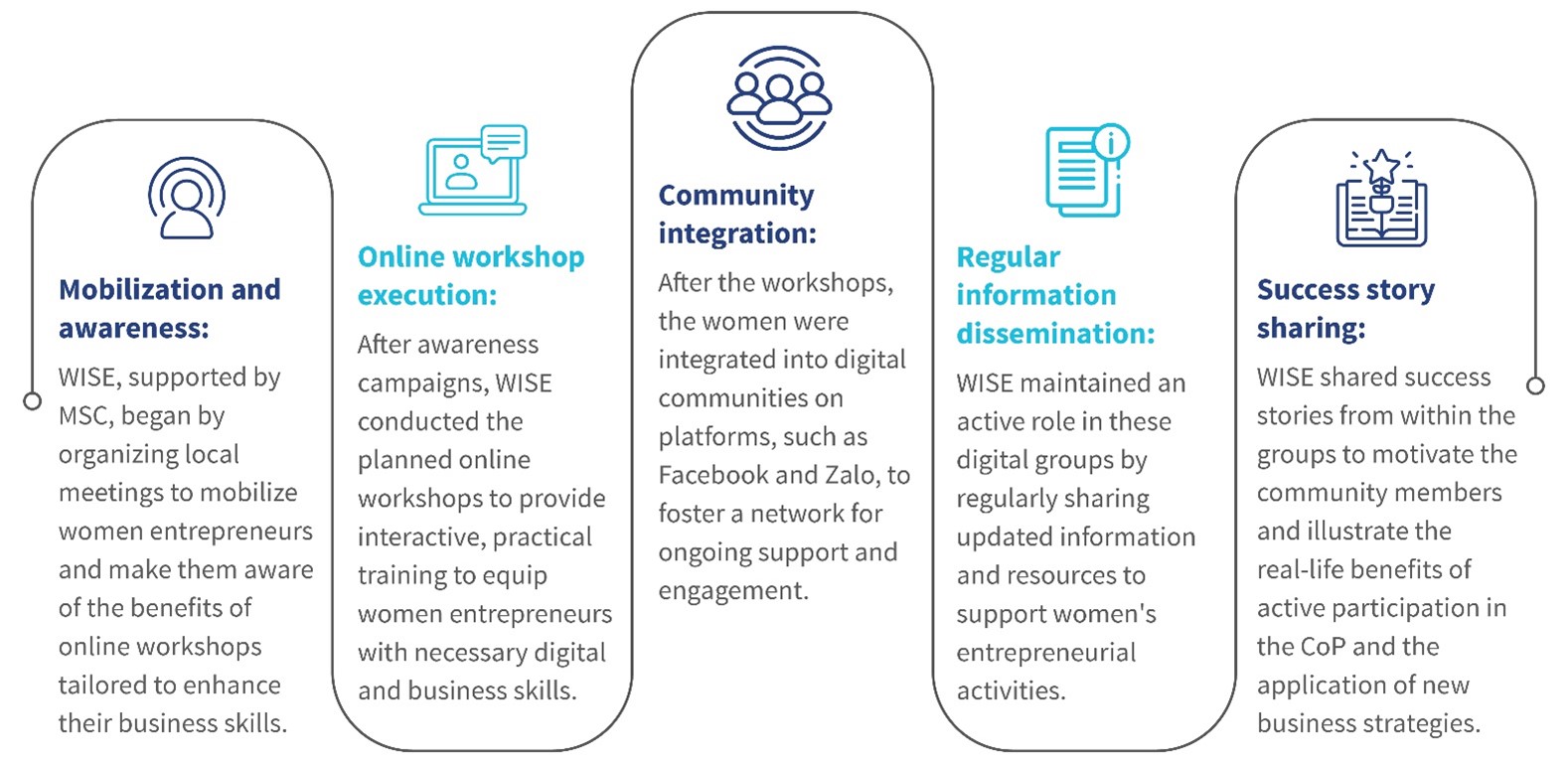

Figure 3: Steps involved in the set up of the CoP in Vietnam

Vietnam’s CoP activities had multifaceted outcomes. These ranged from enhanced individual and organizational capacity for work-life balance to the creation of supportive online communities and increased access to vital resources.

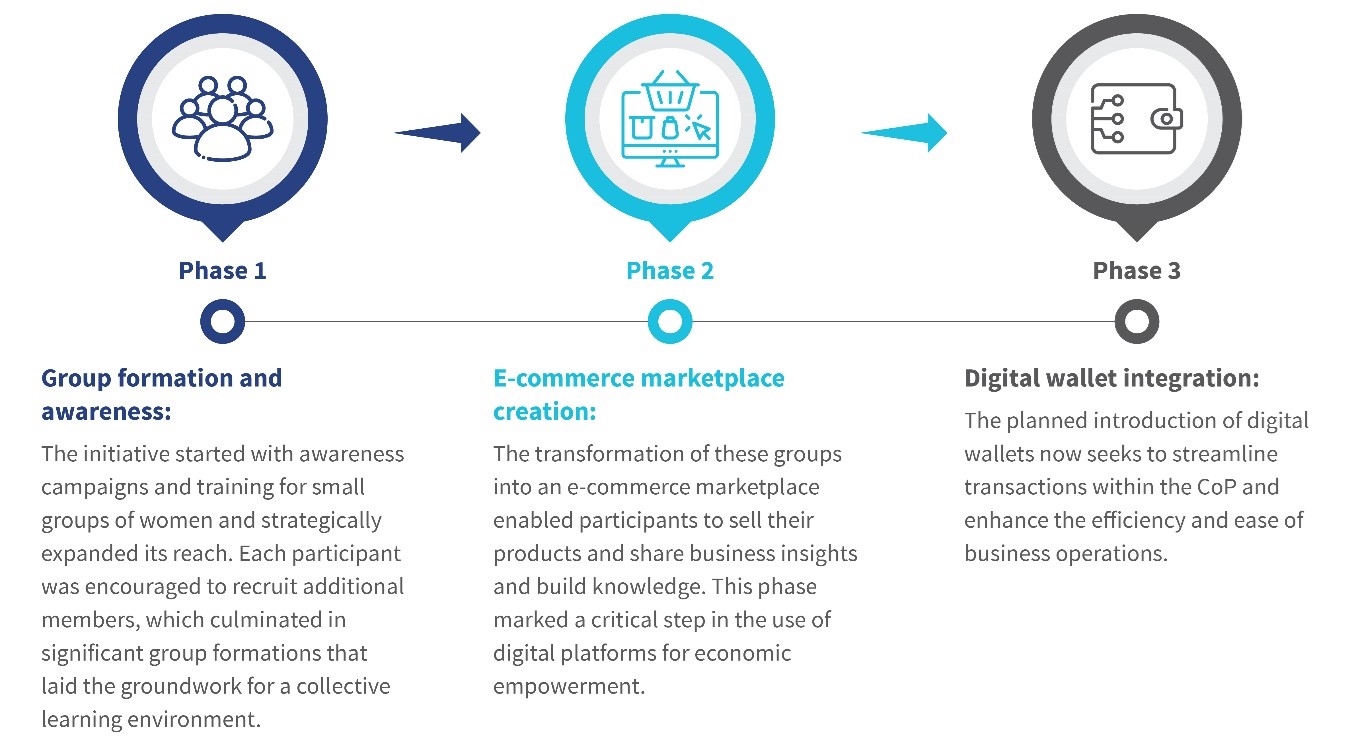

In Nepal, MSC’s partnership with Women Act Nepal and other local entities shows a comprehensive three-phase CoP initiative to empower women entrepreneurs across several provinces.

Figure 4: Steps involved in the setup of the CoP in Nepal

We measured our CoPs’ impact through tangible and intangible metrics. Increased member engagement and knowledge exchange and significant business improvements indicated success. We engaged with more than 12,000 rural WLBs across India through WhatsApp groups and more than 20,000 women globally. We ran pilots with more than 10 cooperatives under the SEWA Federation. When the women in these groups were educated about the CoP platforms, they received the instructions well and felt confident enough to share voice notes in the group. These outcomes validated the effectiveness of CoPs and highlighted their potential as catalysts for change and development.

The way forward

The future integration of CoPs into organizational structures, particularly in lower-income sectors, presents an exciting opportunity for widespread learning and empowerment. New digital collaboration tools and methodologies promise to revolutionize how CoPs function and make them more accessible and impactful. As CoPs gain global traction, they will emerge as crucial channels for knowledge sharing and innovation across borders. Their global perspective would enrich the CoP model and ensure its relevance in an increasingly interconnected world.

The cultivation of knowledge through CoPs is more than just shared learning. It builds a supportive network that transcends geographical and cultural boundaries. CoPs offer a platform for empowerment, innovation, and collective growth, especially for women-led businesses that face unique challenges. Our experiences across different regions underscore these communities’ transformative power as they chart a future where knowledge is freely shared and collective wisdom is key to overcoming challenges.

We at MSC seek to strengthen existing CoPs under our partners and identify newer engagement areas to build more collaborative cohorts. Our objective is to weave the fundamentals of CoP as proof of concepts, so WLBs see their value, ingrain these as an inherent part of their structure, and build and nurture these communities.

Women’s entrepreneurship: What can be done to improve access to finance?

Africa has emerged as a melting pot for female entrepreneurship in light of the recent surge in attention to entrepreneurship. The continent has the highest rate of female entrepreneurship, at 24%, ahead of South-East Asia Pacific (11%) and Europe (9%). Moreover, female entrepreneurship in Africa contributes between 7% and 9% of its GDP, or some 150 to 200 billion dollars.

Yet, despite the dynamism that can be attributed to women’s entrepreneurship in context of these rather glowing figures, women face numerous barriers when they attempt to develop their businesses. Access to finance is one of the major issues. What are the possible solutions to this challenge?

Causes of the financing gap

Worldwide, women’s access to finance remains disproportionately low. The situation is far more alarming in Africa, which starts with unequal access to bank accounts.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, only 37% of women possess a bank account, compared to 48% of men, a gap that has been widening for several years. Women frequently have little capital to start their businesses and are less likely to benefit from private investment or venture capital. “I sell clothes to support my family. I wanted to increase my capital to develop my business. Yet the bank denied me a loan, because, according to them, I do not have strong collateral,” said Karidja Bakayoko, a clothing retailer in Daloa City, Côte d’Ivoire.

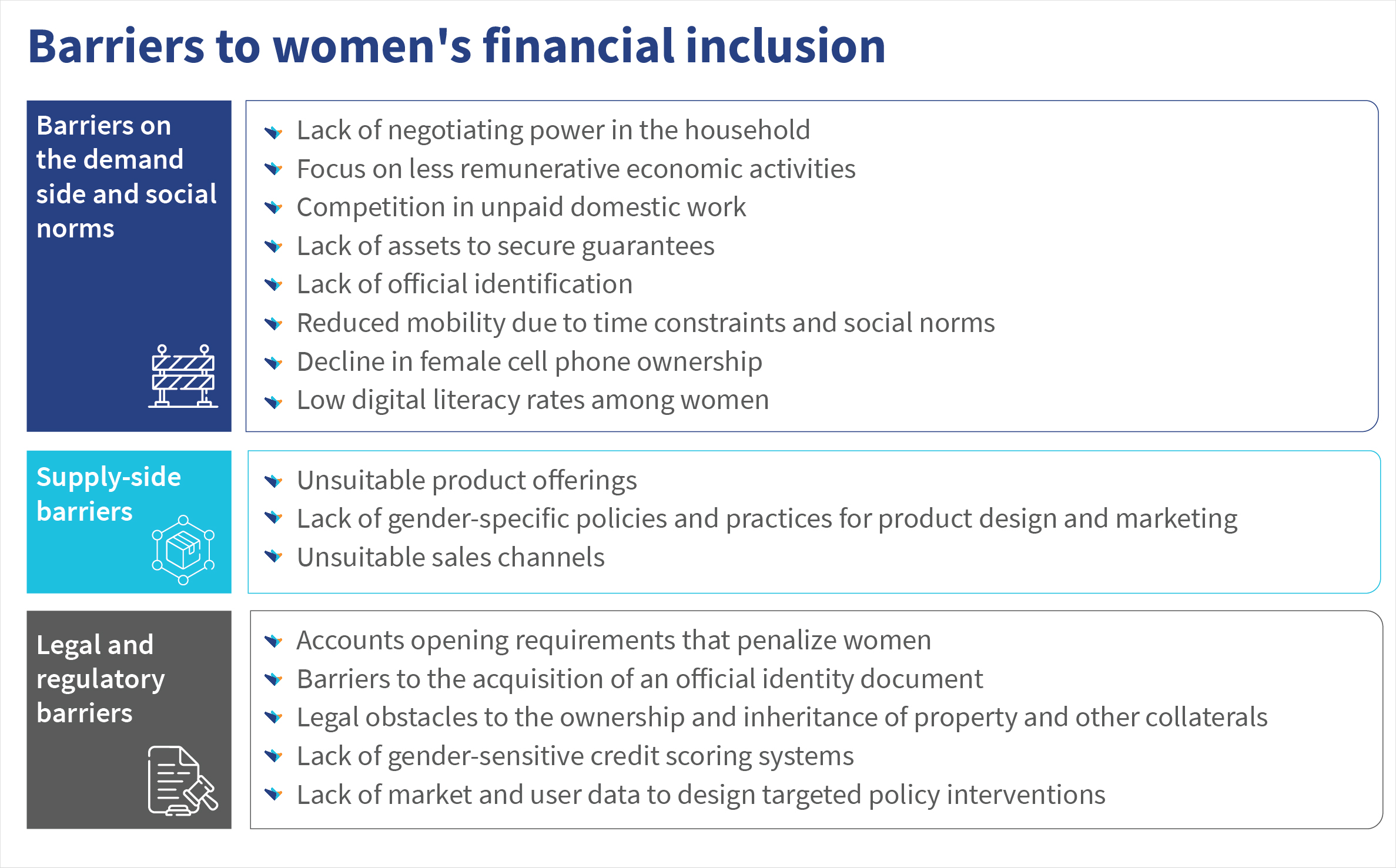

Banks require collaterals that women cannot often provide. Men usually own valuable assets, such as land titles or vehicles, which they can provide as collateral to support some women. Notably, 45% of women in low-income countries have no official identity documents, compared to 30% of men. In addition, women are usually risk-averse, with little financial culture and a fear of failure, which often prevents them from requesting loans. They also have to contend with a lack of family support and a lack of training to develop the skills needed to run a business effectively. Other barriers include personal constraints, such as family projects, spouses’ professional projects, and family responsibilities, alongside women’s poor integration into business networks, and the lack of suitable financial products. In addition, banks’ lack of understanding of women-owned businesses and women’s lack of financial education are barriers to financial inclusion, as shown in the table below.

All these challenges have a negative impact on access to finance for African women entrepreneurs.

All these challenges have a negative impact on access to finance for African women entrepreneurs.

However, when financing and markets are available, women can contribute significantly to their families’ well-being. They can then mobilize savings to prioritize their children’s education. They also contribute to their country’s economic development by setting up businesses that create jobs and wealth.

Initiatives to boost access to finance for women entrepreneurs

Concrete actions are needed to promote women’s access to finance. Governments should introduce financial inclusion policies and regulations that favor women. To this end, several initiatives have already been developed across Africa, such as the Affirmative Finance Action for Women in Africa (AFAWA) program.AFAWA is an African Development Bank (AfDB) initiative that seeks to bridge the estimated USD 42 billion financing gap that affects women in Africa. The initiative is in early discussions with financial institutions in West Africa. AFAWAis also a USD 12.5 million anchor investor in Alitheia IDF Managers (AIM), the first private equity fund of its kind, led by experienced women fund managers that invests in high-growth SMEs owned and run by women in Africa. In 2018, AFAWA provided technical assistance to several banks. AFAWA trained 1,000 women entrepreneurs across the African continent in business model development and financial planning in collaboration with the Entreprenarium Foundation. The aim is to give them the resources they need to access financing easily.

Investment funds dedicated to women akin to Janngo, a venture capital fund run by women that invests 50% of its revenues in start-ups founded, co-founded or benefiting women, should increase even more. In Côte d’Ivoire, the government set up a fund in 2017 to promote SMEs and women’s entrepreneurship with a budget of 5 billion XAF. This fund seeks to facilitate access to bank credit for women entrepreneurs, including startups, across all business sectors. The initiative will provide a tangible boost to financing for women and help advance financial inclusion.

Financial institutions should not stay aloof from these initiatives. They could consider creating women-friendly banking procedures, such as waivers on minimum balances, reductions in collateral requirements, and inclusion of other forms of collateral that are more accessible to women. In addition, financial institutions would benefit if they develop products and services dedicated entirely to women that take their needs into account. They should consider important aspects, such as product simplicity or reliability, when they design these products and services, which are likely to guarantee their frequent use.

We must, however, note that the design of financial services should be accompanied by financial education programs that will enable women entrepreneurs to develop suitable financial skills and behaviors. In short, the goal is to improve women’s understanding of financial services while raising their awareness of the risks involved so that they can make autonomous and responsible financial decisions. It is with this in mind that the Digital Finance Hub has been created to offer everyone the tools they need to develop their business.

Worryingly, a customer base in excess of 1 billion women remain disconnected from financial services and predominantly underserved. To change this situation, FSPs must study women’s customer journeys and use this knowledge to design tailored financial product offerings. The dual benefit will be to transform women’s lives and offer commercial value to financial institutions. Financial institutions would be able to create new products and reach out to women, who are usually not funded. With a tailored offering, the financial institutions can grow their clientele—and their income.

Impact of extreme heat on migrant workers and MSMEs in Delhi-NCR

South Asia is generally very hot, and people have built coping mechanisms to deal with the heat. However, climate change is set to push temperatures higher and increase heatwaves in the near future. Up to 75% of India’s workforce, or 380 million people, depend on heat-exposed labor and at times work in potentially life-threatening temperatures.

MSME workers who work in workshops with heavy machinery, outdoors, or are engaged as gig workers are at a higher risk of heat-related injuries and extreme symptoms. This study seeks to understand the vulnerabilities and challenges informal workers and MSMEs face with regard to extreme heat.

Can locally-led adaptation planning extend the digital and financial inclusion frontier?

Excluded communities

Historically, financial service providers (FSPs) have struggled to include more remote, vulnerable, and poor people into the formal economy. 1.4 billion adults worldwide still do not have a bank account.

The Findex 2021 survey reported that 76% of adults had an account at a bank or regulated institution, such as a credit union, microfinance institution (MFI), or a mobile money service provider. In developing countries, 13% of these accounts were inactive, even when we use the conservative measure that the respondent “did not use their account at all in the previous year.” Given that governments were making payments to support post-COVID-19 recovery in the year before the enumerators conducted the survey, this figure probably understates the underlying inactivity significantly.

The reasons for this exclusion are well known. They include geographical barriers, since limited distance and poor infrastructure in remote areas restrict access to services. This is compounded by economic vulnerability, as poor communities often lack the income or documentation needed to use traditional financial services. Gender disparities further impede women’s inclusion, and a lack of financial capability limits broader participation. Policy and regulatory constraints, such as restrictive policies and high compliance costs, also hinder service expansion.

These excluded people are also often stranded on the wrong side of the digital divide as a result of the lack of access to mobile phones, poor internet connectivity, and low digital literacy compounded by unsuitable user interfaces. They are also most likely to be vulnerable to climate change and have the greatest need for information and financial services to cope with climate events, recover from them, and adapt to build their resilience.

FSPs have not been willing or able to support these excluded people on commercial terms. This is unlikely to change without de-risking, and in some cases subsidies, for them to do so.

Could climate funds be a catalyst?

UNEP estimates that the climate change adaptation costs for developing countries will increase to USD 160–340 billion annually by 2030 and USD 315–565 billion by 2050, which is five to seven times higher than the USD 49 billion of global adaptation flows in 2019-2020.

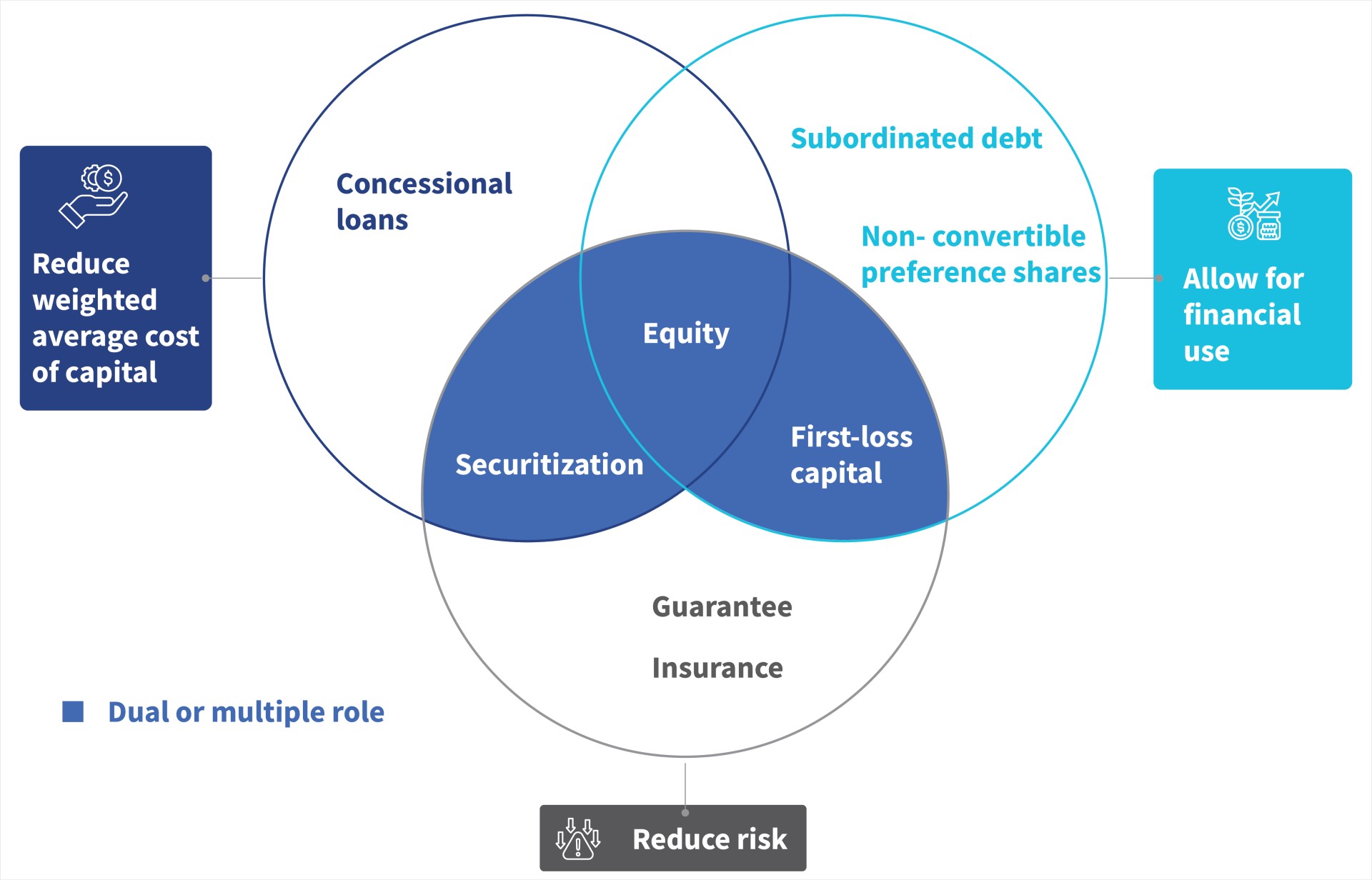

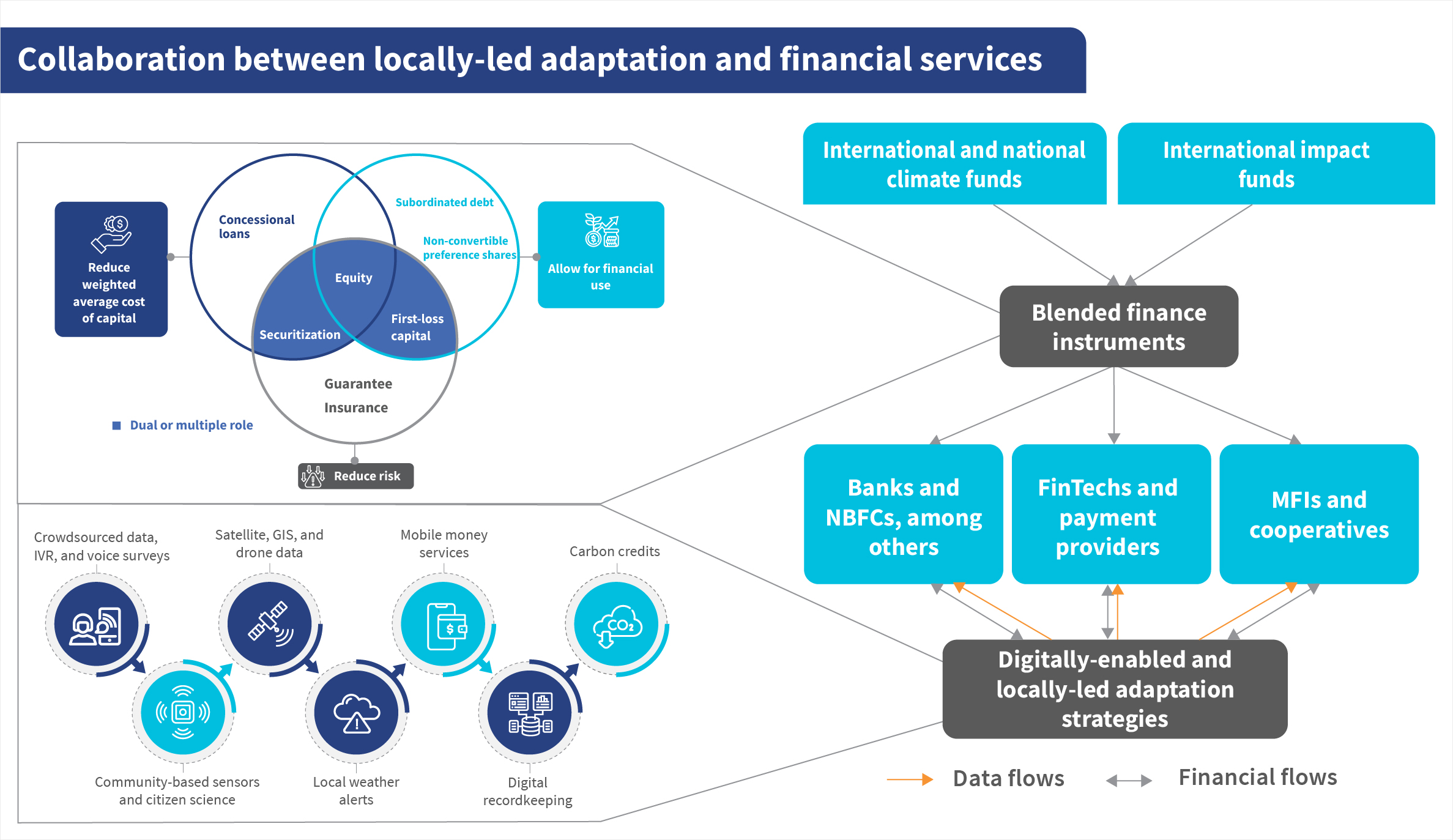

International and national funds, alongside impact funds, could use blended finance instruments to unlock public and private sector capital to address this chasm between the need for finance and its availability. Blended finance instruments can be used to reduce risk, permit capital leverage, and reduce the average weighted cost of capital. Using these instruments in preference to, or alongside, the grants that are most commonly used by many of the climate funds at present, could stretch precious adaptation funds and help bridge the chasm.

What role should blended-finance play?

Can digitally enabled locally-led adaptation turbocharge locally-led adaptation strategies?

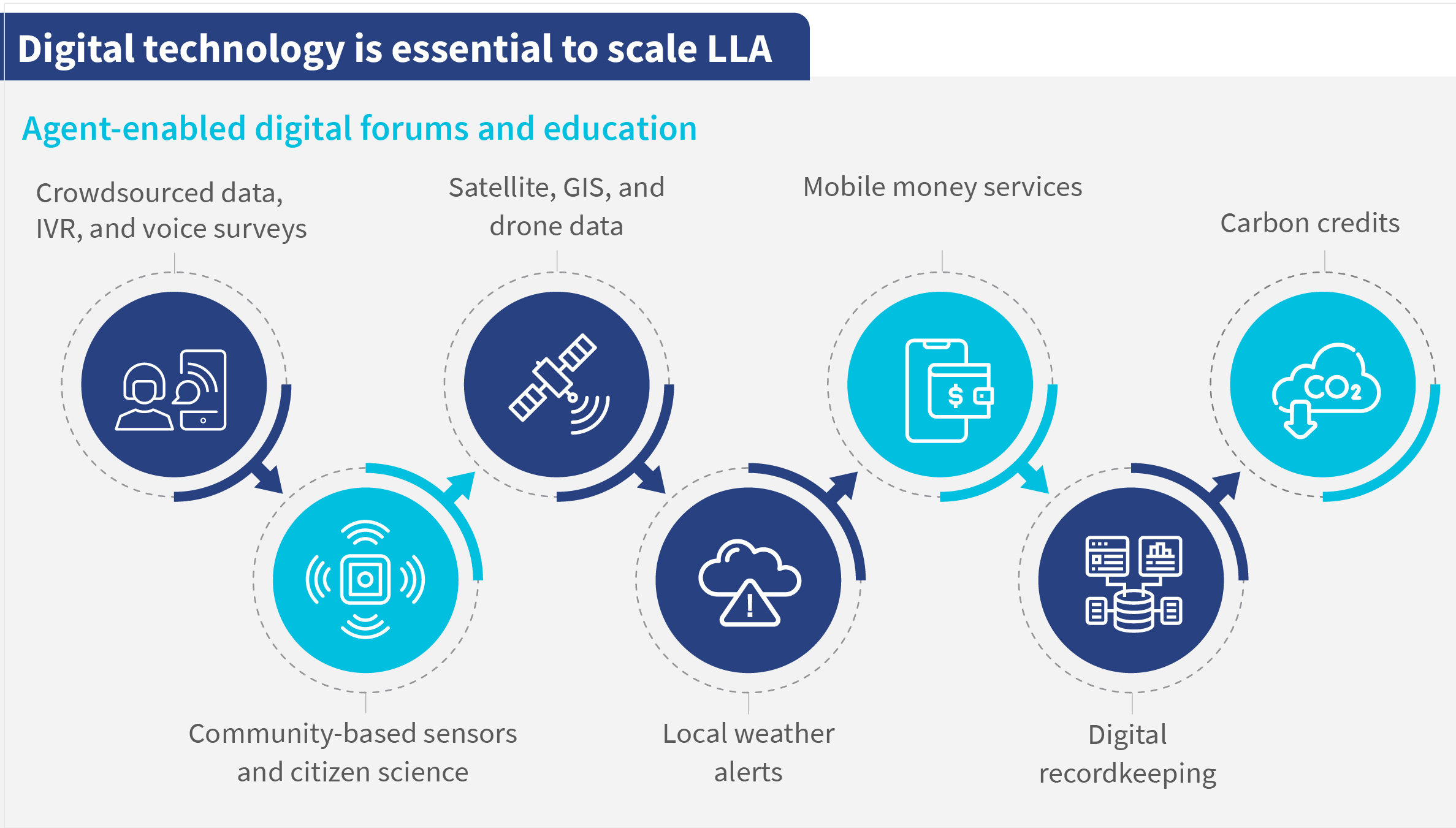

Digitally enabled locally-led adaptation (LLA) is essential to scale and optimize locally-led adaptation strategies. It also offers the opportunity to create digital profiles and thus conduct risk analyses of these populations and their livelihoods.

Digital technologies driven by satellites, crowd-sourcing, and AI, such as those used by CropIn, Ushahidi, and Amini, have great potential to support LLA planning and implementation. Community-based and operated sensors could collect localized climate data for analysis and planning and complement climate change predictions from GIS and machine learning models. As adaptation plans are implemented, local language weather apps, such as TomorrowNow, could provide communities with vital alerts about imminent weather changes to enable them to prepare and respond better.

These technologies can expedite and scale strategy development processes, support implementation, and enhance governance functions, such as monitoring, evaluation, and learning. Additionally, the carbon offsetting programs that could also provide some funds for adaptation often face challenges in the certification of carbon-offset activities and distribution of funds to the intended vulnerable communities. Digital platforms, such as CaVEx, present opportunities to overcome these obstacles and ensure more effective implementation and payment of benefits.

Communities can use community-based and operated sensors, satellite and drone services, and feedback platforms to report progress and challenges in real time. Mobile money services and digitally-enabled smart contracts could be used to ensure the transparent and efficient delivery of funds for adaptation projects against performance targets. Furthermore, digital payments and digital record-keeping could ensure the accountable use of resources and thus create important digital trails that facilitate credit risk appraisal and lending by formal financial service providers.

Findings from the Global Findex 2021 survey likewise reveal new opportunities to use digital payments for wages, government transfers, or the sale of agricultural goods, to drive financial inclusion and expand the use of financial services among those who already have accounts. Digitalizing some of these payments is a proven way to increase account ownership. In developing economies, 39% of adults—or 57% of those who had an account with a financial institution (excluding mobile money)—opened their first account specifically to receive a wage payment or receive money from the government.

Opportunities to facilitate locally-led adaptation strategies

Indeed, MFIs, credit unions, and other community-based FSPs and their agents are well-placed to facilitate digitally enabled LLA planning and strategy development alongside capacitated local government officials. Doing so would allow FSPs to deepen their understanding of the needs, aspirations, and behaviors of these climate-vulnerable communities, and learn how they mitigate the risks they face. This, in turn, would allow FSPs to use the funds and blended finance instruments offered by international and national climate funds and impact investors to provide financial services to these communities.

Bridging the digital divide

In addition, the use of digital technologies as part of the LLA process provides us a unique opportunity to get these populations used to digital devices and data and comfortable with them. These LLA-driven use cases provide opportunities to offer real value to these hard-to-reach communities, increase their resilience, and demonstrate the benefits of digital tools to them. Many of the most vulnerable communities comprise smallholder farmers who could benefit from digitally-enabled value chains and financial services.

Climate change, and the LLA response to it, could very well become an essential bridge across the digital divide for these farmers and others currently stranded in the analog world.

Can AI help with locally-led adaptation: The solutions

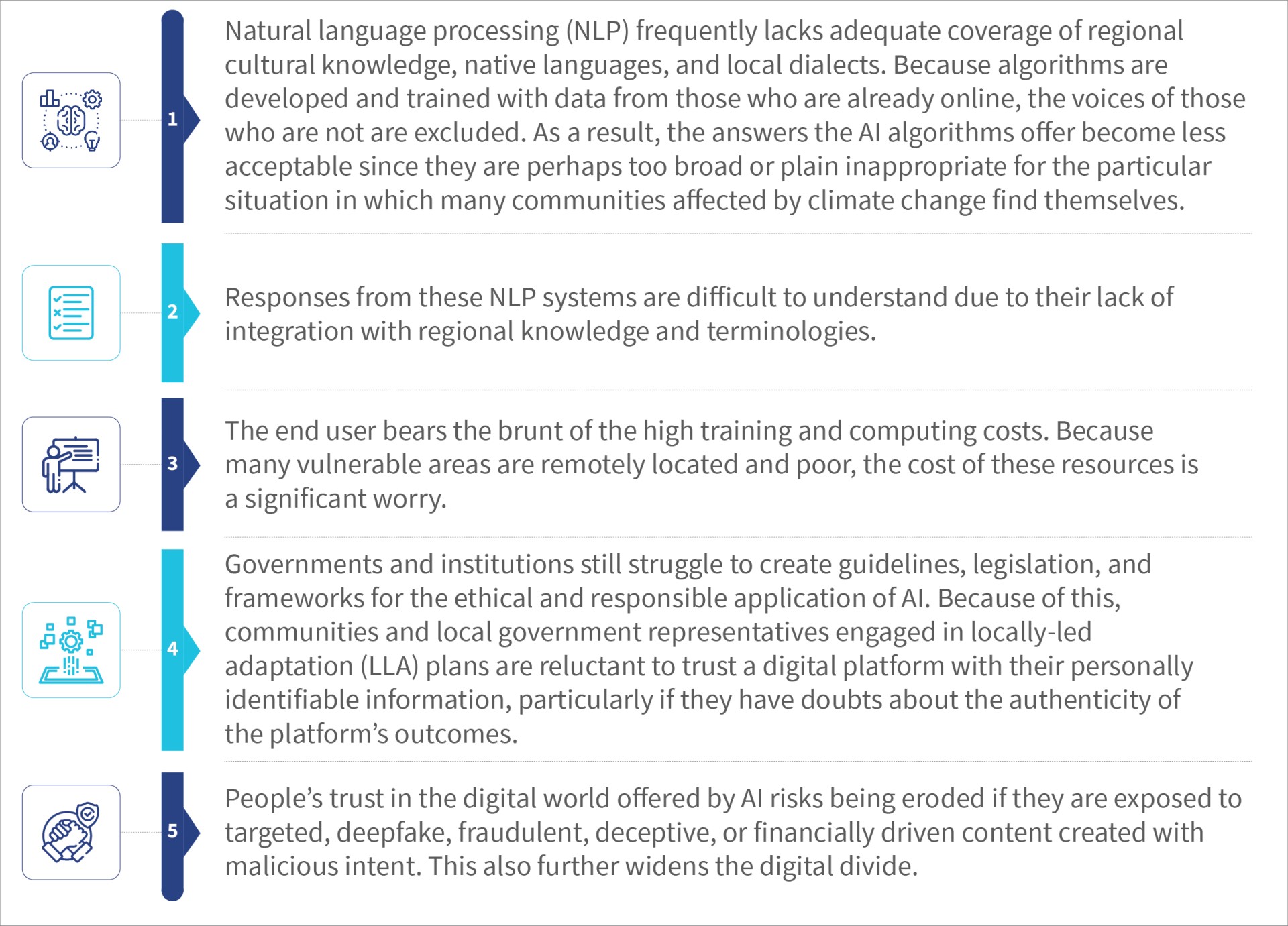

We have examined the causes and effects of the digital divide—where the most vulnerable members of society are stranded in an analog world—in the blog “Can AI help with locally-led adaptation? The challenges.” Despite efforts to close this gap through AI-powered modern technologies, the adoption and penetration of these technologies have fallen well short of expectations. We can summarize the problems as follows.

We need to address five aspects here:

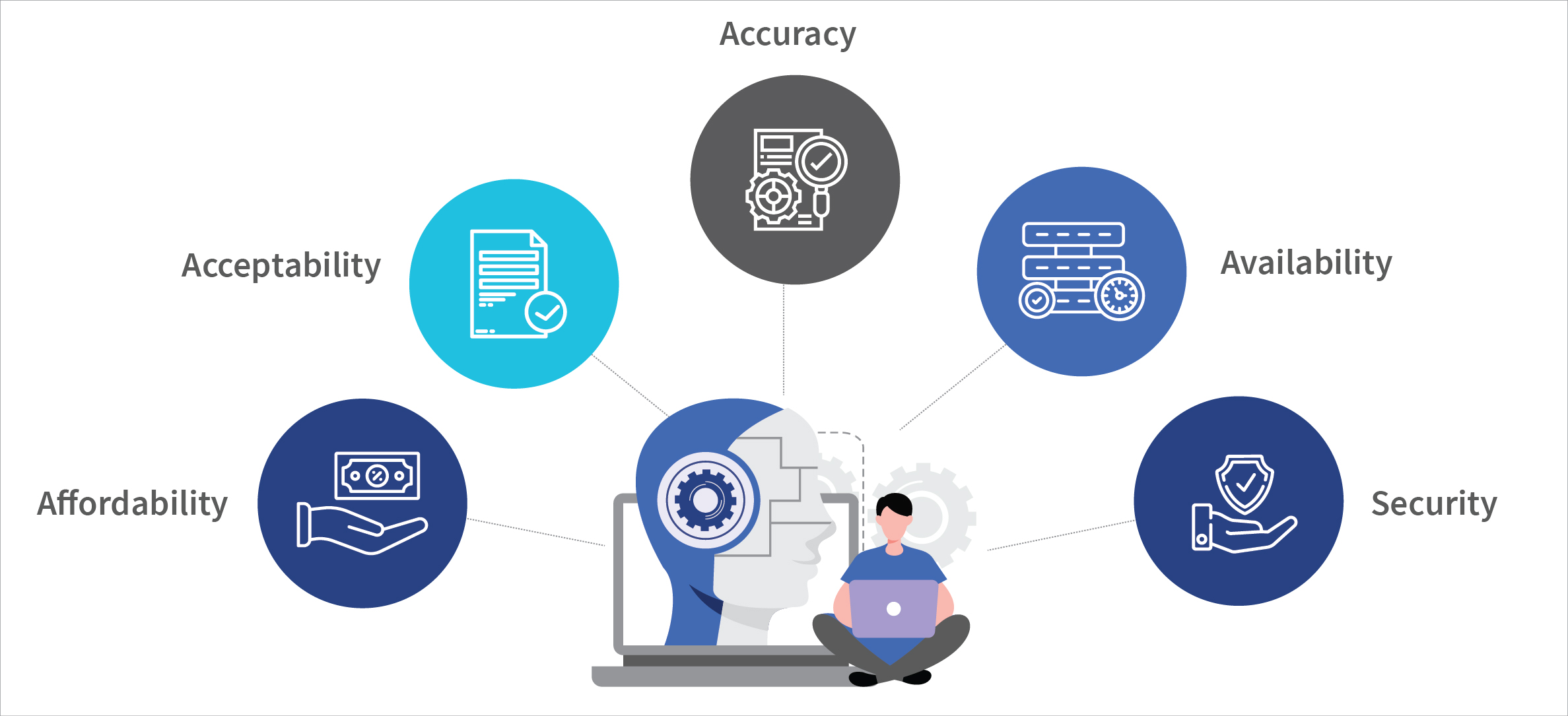

Data is the main source of dependency for any nation’s AI journey. Governments must create their frameworks, policies, and goals for AI and engage in its development. Affordability will be easier to achieve if the state invests to collect, preserve, process, and operationalize data. For example, India’s AIRAWAT AI supercomputer, which is among the world’s 100 most powerful systems, helps enable technology and AI for the welfare of common people and contributes to their socioeconomic growth.

The National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence lays down the foundational roadmap to India’s AI journey. The work on the Indic language set allows content to be collected and delivered in Indian languages. With state backing to process vast amounts of data, private businesses can create last-mile solutions and delivery apps that are more cost-effective for the underprivileged population. These private institutions can then focus on educating the public on digital platforms. Here, too, the state’s capacity for broadcasting and information dissemination can be used to reduce the cost further.

Development organizations have also played a big role to bring down the affordability cost through their support of initiatives for multiple public use cases, such as healthcare to the doorstep, tele-consultancy, and medical interventions to detect symptoms, among others. For example, People+ai has been working on a strategic initiative Adbhut India (AI), which seeks to build ecosystem-level solutions actively across a spectrum of multiple projects in agriculture, healthcare, education, and governance. As more and more players participate in the ecosystem collectively and competitively, the quality of solutions will improve, and their costs will fall as per the market economics.

The acceptability of the solution for LLAs depends on the content’s localization and relevance. This means that the content should feature native terms and dialects wherever suitable. To help, the state or pertinent departments should create, oversee, and implement a local lexicon and glossary that can supplement the trained LLM models with techniques, such as retrieval-augmented generation (RAG). RAG is a method that uses information retrieved from external sources—in this case, the localized glossary—to improve the precision and dependability of generative AI models. For example, the armyworm pest has different names in India, such as “girni sena” or “fauji keeda.” In such cases, the RAG technique will supplement the LLM with a localized glossary of names. Similarly, OpenHathi by Sarvam AI has been developing an ecosystem with open models and datasets to encourage innovation in Indian language AI.

The local climate, soil, landscape, temperature range, and species, among other factors, should also augment the trained data to make the delivered content more accurate. Some data is available in government departments in silos, but its quality in terms of structure, relevance, and accuracy remains a big concern. Development organizations can play a vital role here to facilitate data collection by encouraging the use of digital technologies for LLA.

Availability is easy to achieve if all former aspects are in place. The design of the “last-mile” application should be intuitive for users and seek to reduce the digital divide through a suitable delivery mechanism. People who cannot read can be helped using audio or video content. Places with poor or no internet connectivity can be included through the use of state capacity of information broadcast and community service. Most of the LLAs are “employed” to render their service, and these organizations should also contribute through their corporate social responsibility. As discussed earlier, NLP trained in local dialects and languages is the key to success.

CICO agents, MFI staff, agricultural extension agents, and CBO or NGO staff can help those without smartphones access AI solutions. These agents can provide awareness, trust, and capacity building for AI solutions that require digital payments or transactions, such as e-commerce platforms, digital credit, or insurance products. The agents can enable people to invest in or adopt AI solutions for agriculture, such as smart irrigation systems, precision farming tools, or crop monitoring devices. Agricultural extension agents can also provide feedback and evaluation for AI solutions and facilitate the exchange of knowledge and best practices among farmers and other stakeholders. CBO or NGO staff can also advocate for the rights and interests of farmers, especially smallholders, and women, and ensure that AI solutions are ethical, responsible, and inclusive.

Security and privacy are the most difficult aspects of all the concerns. Technology is just a tool, a weapon that can be used for both positive and negative outcomes. Any technology’s positive intent, promises, and capability have never been able to outrun the malicious intent to exploit loopholes, gaps, and back gates left unguarded due to a lack of strong foundational policies, laws, frameworks, checks, and measures. A coordinated and collaborative approach is required among multinational governments and private institutions to share, adapt, and enforce these countermeasures to keep bad elements at bay as far as possible.

Laws now need to go beyond border jurisdiction to spread the cover. Nations can no longer match the potential of AI in isolation if they want to ensure the safety and privacy of their citizens’ data and well-being. This is particularly important in the context of farmers, as discussed in the Climate Resilient Agriculture Virtual Club. Policymakers and regulators must develop farmer-centric data governance guidelines to implement fair and equitable data governance models that prioritize farmer participation even as they guard farmers against disadvantages and exploitation.

People hesitate to overcome the digital divide primarily because of a fear of fraud, cybercrimes, and misuse of personal information. Interestingly, advanced AI can analyze non-personal data over time to identify, for instance, farms and their owners, even without direct access to personal information. Digital literacy must be improved to address the hesitation. Governments and nonprofits must actively educate farmers on the digital skills needed for their development in rural areas. This education should also cover their rights and obligations in the digital world. Moreover, it is time for laws to recognize the “right to consent” as a basic right and integrate it into the educational curriculum for all citizens.

Conclusion

We must tackle the challenges of affordability, availability, acceptability, accuracy, and security to successfully integrate AI into development initiatives, particularly for people with low literacy. AI adoption depends on comprehensive data management and supportive government policies. Localization of solutions to align with cultural and linguistic needs is key to better acceptability and accuracy, while accessible design and community engagement are vital for broad availability. If security and privacy concerns are to be addressed, coordinated efforts will be needed across governments and institutions to establish protective measures and ethical standards.

A focused effort on technological innovation, digital literacy improvement, enactment of supportive legislation, and multi-sector collaboration is imperative. Such a holistic strategy will address immediate challenges and position AI as a powerful tool to foster inclusive LLA and, indeed, development in a broader way.