Mr. Md. Arfan Ali, President and Managing Director of Bank Asia, and Mr. Graham Wright, Group Managing Director of MSC signed the agreement on behalf of respective organizations. The event was also presided by Mr. Ala Uddin Ahmad, CEO of MetLife Bangladesh, and Mr. Krishna Thacker, Asia Director of MetLife Foundation.

Both parties signed the agreement to undertake a project named “Livelihood and income generation for post-e-centers, and building resilience and financial health for LMIs in Bangladesh.” Through this project, MSC intends to work with Bank Asia to build the resilience of agents and improve the financial well-being of users of financial services in Bangladesh.

Bank Asia aims to strengthen the front-end infrastructure of the post e-centers of Bangladesh Post Office, train its agents and staff, and increase the bouquet of services that LMIs need. MSC will help Bank Asia strengthen the infrastructure of postal agents to make them transaction-ready. The overall objective is to build the resilience of the postal agent banking channel to strengthen the financial health of the LMI population in Bangladesh.

In the event, Mr. Md. Arfan Ali said, “Post offices across different parts of the world offer postal banking services, but Bangladesh is far behind. Bank Asia has taken the initiative that the post office in Bangladesh will be the Postal Bank and be connected with international bodies such as the postal association worldwide and bring banking services to doorstep people.” He believes that this memorandum of understanding between MSC, Bank Asia, and MetLife Foundation will make credit facilities easier and give people extra boost-up to the post banking initiative. He hopes that it would create a new horizon by including the marginal people to banking services.

Mr. Graham Wright spoke on behalf of MSC. He noted, “We are excited to use our experience

in other markets and support Bank Asia to strengthen its agent network further. Building on our previous work, MSC seeks to help its agents build resilience, especially since the pandemic. We will help Bank Asia’s customers build better financial well-being.”

Bangladesh has made rapid strides to bring financial access to low and moderate-income (LMI) customers in the past few years. This has increased formal banking accounts from 20% (in 2014) to about 50% (2017) of the adult population. However, the problem of financial access and usage persists in Bangladesh.

This trend is rapidly changing with collaborative efforts from public and private sector providers. With active support from MetLife Foundation, MSC and Bank Asia intends to help millions of people access and use financial services more conveniently with lower opportunity costs.

Bank Asia has already built one of the most significant agent banking networks locally and globally, collaborating with private and public organizations. Under this new business concept, Bank Asia will provide financial services through postal outlets joining hands with the postal department of Bangladesh.

MicroSave Consulting (MSC) is an international financial inclusion consulting firm dedicated to strengthening institutions’ capacity to deliver market-led, scalable financial services to all people. Over the past 20 years, MSC has designed and implemented nearly 75 digital finance projects across Africa, Asia, and Latin America with more than 200 banks, MFIs, and MNOs to develop and test 200+ different financial inclusion products and channels.

MetLife Foundation is committed to expanding opportunities for low- and moderate-income (LMI) people worldwide. The foundation partners with nonprofit organizations and social enterprises to create financial health solutions and build stronger communities while engaging MetLife employee volunteers to help drive impact. Since 1976, MetLife Foundation has contributed nearly USD 1 billion to build stronger communities. Their financial health work has reached more than 17.3 million low- and moderate-income individuals in 42 markets. The foundation also has a strong footprint in Asia. In Bangladesh, it has been supporting efforts to enhance the financial health of LMI people through targeted interventions, especially for women and micro-merchants. MetLife Foundation continues to support the development of financial health in the region through its flagship i3 Program.

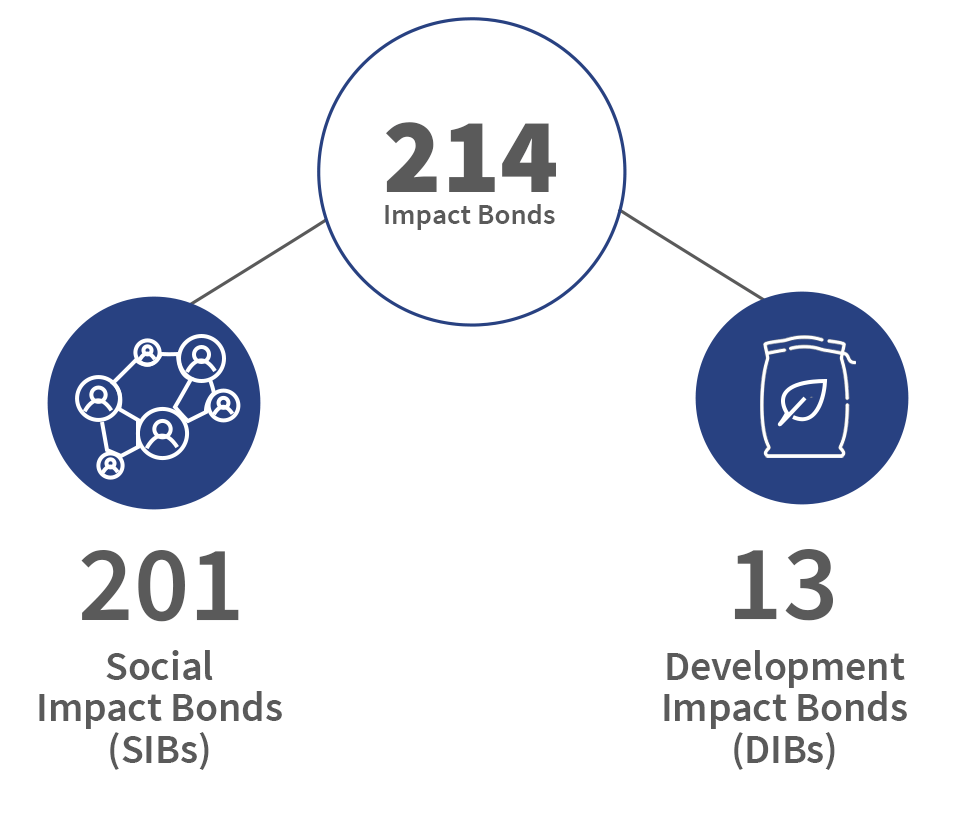

Since the first SIB launched in

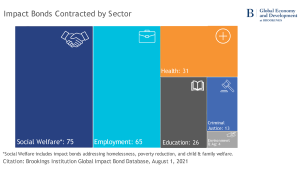

Since the first SIB launched in  The potential role for SIBs in India and the developing world

The potential role for SIBs in India and the developing world