This white paper explores data sharing as a key pillar of digital public infrastructure, which operationalizes interoperability in practice. It presents a broad conceptualization of data sharing systems that combines technology solutions, policies, and governance. These systems highlight trust and data protection by design as core features. This paper explores how these systems can improve public service delivery based on case studies from Brazil, Cambodia, Mauritius, and Uganda. Further, the paper outlines diverse models, use cases, challenges, and enabling factors. It also discusses emerging efforts to build open data ecosystems to drive AI innovation in public service delivery. This paper concludes with recommendations for governments and ecosystem stakeholders to scale data sharing systems for more accessible and efficient public services in LMICs.

Reaching the unreached: Strengthening last-mile delivery for particularly vulnerable tribal groups (PVTGs)

Gumla’s story highlights the importance of strengthening last-mile delivery of financial services for particularly vulnerable tribal groups (PVTG) through closer alignment with on-ground realities.

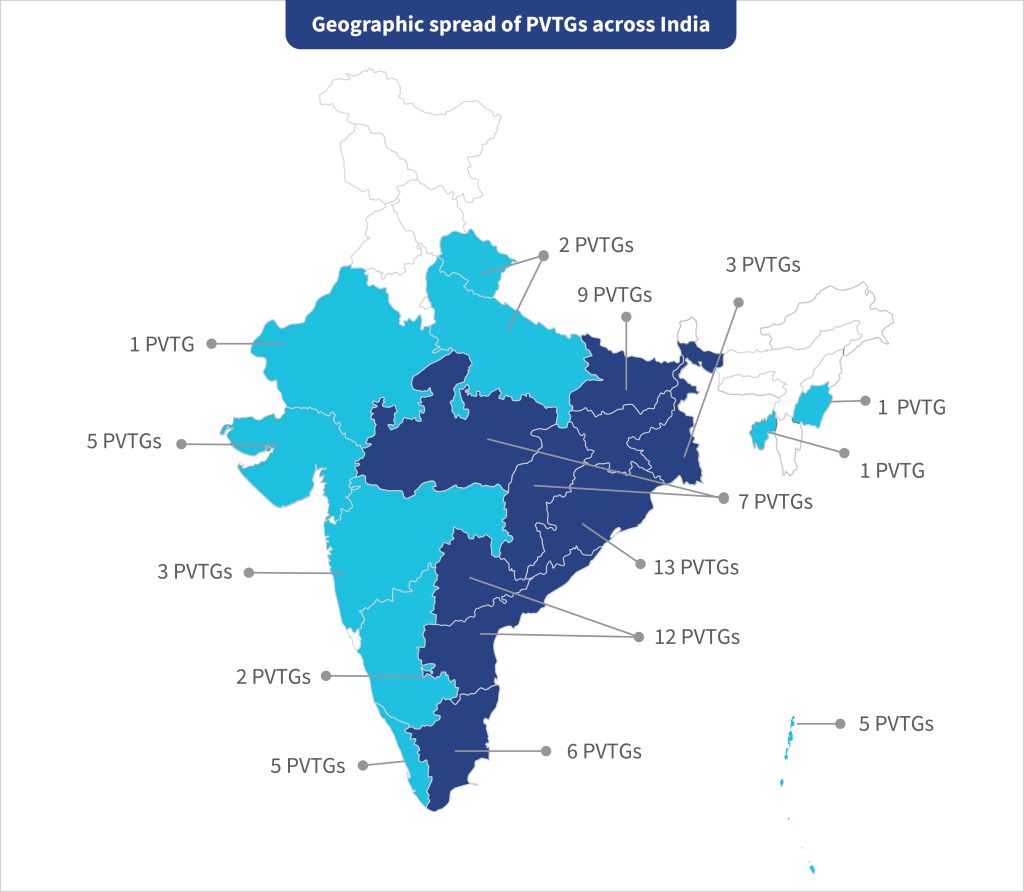

Across India’s diverse tribal landscape live 75 PVTGs, spread across 18 states and one union territory. They comprise around 2.8 million people. The Dhebar Commission first identified these communities as ‘Primitive Tribal Groups (PTGs)’ in 1973. The government reclassified them as PVTGs in 2006. These communities have low literacy levels, pre-agricultural technology, and subsistence-based economies. Often, they also have declining populations..

Over the past decade, national and state governments have intensified efforts to reach these people. The Pradhan Mantri Janjati Adivasi Nyaya Maha Abhiyan (PM-JANMAN) mission began in 2023 with an allocation in excess of INR 240 billion (approximately USD 3 billion).

The Aspirational Blocks Programme (ABP) by the NITI Aayog has generated renewed momentum in bridging historical gaps. Under ABP, block-level convergence mechanisms and locally adapted delivery approaches seek to align welfare systems with the lived realities of PVTG communities. Recent results include the completion of 136,000 houses and the establishment of piped water in more than 7,400 villages. These efforts also improved electricity and mobile connectivity.

Delivery models of welfare, financial inclusion, and social protection services often work well when people have access to regular services and can navigate written or digital processes. They run smoothly when people have standard documentation, predictable income, and stable mobility patterns. While these conditions hold in some contexts, they do not align with settings shaped by remote geographies, seasonal livelihoods, linguistic diversity, and strong community-based social structures.

MSC drew from field engagement and evidence to examine last-mile delivery of public and financial services for PVTG communities using the PACE lens, focusing on:

Delivery models encounter multiple constraints: distance, mobility, and predictability

The first layer reveals that service delivery models are anchored in formal systems. In many PVTG habitations, engagement with public systems is difficult because settlements are dispersed across forested terrain, and their mobility is dependent on their livelihoods rather than access to services. Banking infrastructure data reflects this gap between service locations of banking touchpoints and everyday mobility patterns of PVTG households. In Maharashtra, for example, nearly half of the blocks with tribal population currently lack a bank branch or ATM, and only 58% of tribal women have active accounts compared to 78% statewide.

As connectivity expands, these regions hold potential for greater participation in financial systems. Digital connectivity is gradually expanding access options. Under the 4G saturation initiative, the government covered 900 PVTG villages so far, and 500 mobile towers were installed in six months. Complementing this, BharatNet has connected more than 210,000 gram panchayats to expand digital pathways for welfare and financial services. This expansion, however, does not automatically translate into last-mile usage. In practice, whether digital services are used often depends on how transactions are perceived and socially validated at the community level. In a small market settlement of Tripura, merchants continue to prefer cash, since “with cash, the work feels complete,” as one shopkeeper noted. Seeing neighbors receive instant confirmations has helped digital tools feel increasingly dependable. Field interactions suggest that effective access depends less on services being available and more on transactions being socially verifiable- where people can see, hear, or confirm through trusted networks that payments have gone through.

When communication systems rely on text, but engagement is built on trust

Another area where service delivery becomes nuanced for PVTGs relates to how people receive and interpret information. Many public systems rely on written instructions, standard templates, and forms. In contrast, PVTG communities often prefer oral communication and rely on trusted interpersonal networks and familiar social settings.

MSC’s field experience from Muniguda block in Odisha illustrates how customized communication pathways shape engagement. In several PVTG habitations, information about banking and welfare services circulates primarily through verbal exchanges and trusted local contacts rather than written notices or formal announcements. Participation in service camps is higher when information is conveyed by familiar individuals, and lower when communication relies on impersonal or text-heavy formats.

Another hurdle is the local dialects that most households primarily speak. Literacy among PVTGs is estimated to be between 10% and 44%, whereas it is 74% nationwide. As a result, information may be technically available but not meaningfully accessible.

Initiatives, such as Bhashini, demonstrate how digital public infrastructure can support inclusive communication. This platform enables real-time translation across scheduled and tribal languages, both through speech and text. Such language-enabled platforms complement trust-based, oral communication by aligning language, medium, and messenger.

From awareness to enrolment: navigating processes on the ground

Once households decide to engage with public services, the nature of interaction shifts to process navigation. Evidence from a 10-district study in Jharkhand indicates that the Janani Suraksha Yojana did not cover 67% of PVTG women, compared to approximately 63% across India. Despite the modest difference in coverage levels, the comparison draws attention to how documentation requirements and process complexity intersect with literacy, language, and mobility constraints in PVTG contexts.

Similar observations can be seen in community-led group spaces. In Chhattisgarh, women who attend financial literacy sessions prefer seating arrangements that align with local customs. This preference for familiar settings is echoed in PVTG habitations in Jharkhand, where community meetings are most effective in open spaces rather than offices. “Here, we feel more comfortable asking questions,” a member observed. When conversations with community members move at a pace shaped by group discussion and contextually relevant set-ups, participation deepens and understanding follows naturally.

Correspondingly, women’s participation in self-help groups in several PVTG geographies remains below 15% compared to 21% nationally. These numbers highlight lower participation in formal group-based arrangements among PVTG women, pointing to the need for further analysis of how platform design and social context shape engagement.

Correspondingly, women’s participation in self-help groups in several PVTG geographies remains below 15% compared to 21% nationally. These numbers highlight lower participation in formal group-based arrangements among PVTG women, pointing to the need for further analysis of how platform design and social context shape engagement.

Open-space community meetings in Dumri block, Jharkhand, support participation in PVTG habitations

Several states are responding to these contextual factors. In Gumla district, Jharkhand, a helpline operated by a PVTG community member combines trust with practical guidance and provides Aadhaar and documentation support in the local dialect. Models, such as BC Sakhis, locally tailored NRLM financial literacy campaigns, pictorial Information, Education, Communication (IEC) materials, and community radio, similarly contribute to improved comprehension and reduced hesitation. Alongside such measures, the district also adopted an Awareness–Enrolment–Troubleshooting (AET) approach, where information dissemination is complemented by enrolment assistance and support to resolve documentation or account-related issues that emerge during access. Rather than treating engagement as a one-time interaction, this approach recognises the need for continued handholding across stages in contexts shaped by literacy, language, and mobility constraints.

Taken together, these examples illustrate how enrolment processes are being adapted on the ground through local language support and familiar social settings in select states.

Livelihood rhythms and financial engagement

Livelihood and income further shape how households engage with financial and welfare systems. For many PVTG households, incomes are seasonal, informal, and linked closely to natural cycles. They earn from forest produce, marginal farming, or daily wage labor. Therefore, even small disruptions, such as illness or delayed payments, can hurt their financial stability.

These realities shape how households interact with formal financial systems. Products designed around regular incomes and fixed repayment schedules may not always align with seasonal cash flows. As a result, households may engage cautiously or intermittently, even when access is available.

Livelihood initiatives linked to shared production offer insights into between livelihood cycles and financial engagement mechanisms can support more stable engagement. In a premium indigenous rice variety, which linked them to better markets and more predictable incomes.

Similarly, in areas where women’s SHG federations are structured around seasonal earning patterns, monthly household incomes have increased by up to 22%. These experiences show how livelihood programs grounded in local economic rhythms can help households strengthen resilience and sustain engagement with formal systems.

Similarly, in areas where women’s SHG federations are structured around seasonal earning patterns, monthly household incomes have increased by up to 22%. These experiences show how livelihood programs grounded in local economic rhythms can help households strengthen resilience and sustain engagement with formal systems.

Jeeraphool cultivation by PVTG farmers in Mahuadanr block, Jharkhand, reflects how collective livelihood platforms support more predictable incomes

Implications for policy and program design in PVTG contexts

In policy and program design, services for PVTG communities are more effective when delivery arrangements reflect local work patterns, mobility, and access constraints. Services are easier to access when they are available at right times and places, and when information is shared through trusted local channels and familiar languages. Participation is also shaped by seasonal livelihoods and limited financial buffers, which make it difficult for households to engage if services require repeated visits or loss of income. Engagement tends to be more sustained when local intermediaries support communities in navigating public systems and resolving issues over time. Across several PVTG areas, district administrations are beginning to adapt delivery approaches by combining improved access with clearer communication and practical process support, as reflected in initiatives such as PM-JANMAN and the Aspirational Districts and Blocks Programme. As a development partner under these programmes, MSC supports districts in identifying locally grounded models that help move from outreach to more consistent and meaningful participation.

Financial inclusion in tribal realities

In many tribal communities, access to financial and welfare services requires multiple visits across difficult terrain, limited connectivity, language barriers, and repeated documentation. Through its on-ground interventions, MSC (MicroSave Consulting) reveals that legacy delivery models often fail because they expect communities to adapt to rigid systems. MSC worked closely with communities and district administrations to redesign service delivery. This approach seeks to understand community needs, resolve issues in one place, align outreach with daily routines, and build trust through local networks. This flipbook captures how adaptive delivery turns access into impact.

Gender-Intelligent banking is the key to unlock Kenya’s untapped market

Christine is a market vendor in Machakos in Kenya, with 17 years of experience. She does not have a formal bank account but uses informal digital financial services (DFS) to save, borrow, and transact. She borrows weekly for stock, school fees, or medical emergencies, but high fees, unclear terms, and limited knowledge of loan products put her at risk.

Eunice, a fishmonger at Apida Beach in Homa Bay County, Kenya, often turns to local lenders known as “Maasai” for quick loans. Informal lenders charge usurious high rates, as for every KES 1,000 (USD 7.70) borrowed; the borrowers pay KES 100 (USD 0.77) daily until the original amount is repaid. Even a small loan of KES 10,000 (USD 77) carries an effective annual interest rate of more than 360%, which affects Eunice’s already tight margins. This interest rate traps many women like her in cycles of debt, which makes it difficult for them to grow their businesses or achieve financial stability.

East Africa’s mobile money revolution has turned financial inclusion into a global success story. Yet, for these women, real inclusion remains out of reach. This gap has shifted from access to usage, depth, and value. For financial service providers, it is about opportunity.

The mobile money revolution in East Africa has dramatically reduced the gender gap in financial inclusion. The gender gap in financial access in the region narrowed from 12% in 2006 to 4% in 2024, fueled by enabling policies, mobile penetration, and telecom innovation. However, access is just the first step. Usage is distinct from access and indicates the actual frequency of activity and uptake of financial services.

In Kenya, a gender gap of nearly 11% persists in usage, with a 11% gap between urban and rural women. Kenya’s of women rely more on informal channels, which reflects persistent gaps in meaningful access to formal banking and its use.

This gap in usage offers a glimpse into the daily financial lives of women. A study by MSC reveals that 60% of women rely on informal DFS, table banking, chamas, and Village Savings and Loan Associations (VSLAs for credit. They often choose these informal options over formal institutions, such as microfinance institutions (MFIs) and banks. Such informal sources have been crucial for access, but their unregulated nature and limited financial literacy leave women exposed, and the products rarely meet their diverse financial needs.

For women, such as Christine and Eunice, limited access to fair, flexible formal finance pushes them toward high-cost and predatory solutions. This pattern is widespread across Kenya, particularly among young women, who continue to rely on chamas, local moneylenders, and social networks. In contrast, young men are more likely to use formal accounts, savings, and credit.

Yet, when women access formal or digital credit, the design and behavior of lenders often widen, rather than reduce, the gender gap. MSC’s work in East Africa shows that women tend to receive smaller loans, shorter tenures, and higher interest rates, as they are often perceived as higher-risk borrowers. Women remain the largest underserved segment in financial services, which represents a persistent gap and a clear growth opportunity.

These gaps reflect a deeper issue that financial products are largely designed with a gender-neutral lens, which overlooks women’s realities. Many assume predictable, regular cash flows, but women often earn irregular, seasonal, or daily incomes. Onboarding requires documentation or collateral that women may not control, while delivery channels assume time and mobility that household and caregiving responsibilities frequently limit. Automated credit scoring typically ignores chama records, informal savings, and other community-based financial behaviors.

For women like Christine and Eunice, these gaps are real. In Machakos, women can access Fuliza, M-Shwari, the Women enterprise fund, or moneylenders, but these options often have low ceilings, rigid tenors, and interest rates up to 40%. Instead of profit reinvestments, women spend most of their earnings on repayments. These patterns are common across Kenya, especially among young women, which shows how structural barriers and product design limit access to meaningful financial services.

Financial institutions (FIs) must change their approach to service women user segments that seize this opportunity. Gender-intelligent banking (GIB) is a transformative approach that recognizes and addresses the unique realities and barriers of each customer, and creates solutions designed for their needs. GIB is a systematic approach and offers a clear, operational way for institutions to embed women customer segments-based business across strategy, products, operations, and governance, which turns intent into practice.

Women represent a gap and a growth opportunity in financial services. The closure of the gap in gender usage represents smart business. Women demonstrate stronger repayment discipline, consistent savings, and influence over household finances, which makes them a high-value, loyal customer base. Expanded offerings and increased usage among underserved women could generate an estimated KES 38.5 billion (USD 352 million) in annual revenue. Young women alone comprise more than 10% of Kenya’s population, which represents a demographic with vast untapped potential.

Tyme Bank in South Africa shows components of this approach. Launched in 2019, the GIB approach reached 10 million customers in six years, with 51% of them being women. The bank combines digital banking with accessible cash-in and cash-out (CICO) agents, many of which are run by female “friendly ambassadors.” It offers pay-as-you-go products, goal-based savings, and gender-intentional credit scoring. Tyme Bank became Africa’s first profitable digital bank. This bank holds nearly ZAR 7 billion (USD 403 million) in deposits and outperforms many traditional banks.

In Nigeria, Access Bank shows the power of gender-intelligent strategies through its W initiative and W power loan, which target women-led businesses and combine tailored financial products. These initiatives are supported by W community networks, mentorship, and W academy training, and redesigned delivery channels with internal gender inclusion through the Access Women Network. These efforts, combined with a focus on using gender data analytics and inclusive leadership, have driven a 58% increase in lending to women-led MSMEs within three years. This increase reflects that women now comprise 32% of its customer base, 40% of its loan portfolio, and 41% of its workforce.

In Kenya and Uganda, FIs are beginning to adopt GIB to serve women microentrepreneurs better. Based on MSC’s work and recent GIB training, such as loan limits, unclear rejections, and products that do not fit their needs. These institutions introduce multiple solutions. They experiment with alternative collateral and data sources, such as mobile money activity and chama histories. These alternatives simplify onboarding, align repayment schedules with women’s business cycles. It also embeds financial literacy into the lending journey and enhances outreach by connecting staff directly with women in markets and communities, rather than through branches alone.

As a result, gender-intelligent practices enable a lending ecosystem that reduces debt cycles, strengthens trust, and empowers women as high-potential clients. These practices enable the businesses of these clients to thrive when financial products align with their realities.

These examples show the potential of gender-intelligent banking. However, most efforts remain underused across the sector, which focuses on isolated elements, a single product, campaign, or channel tweak. Early success remains fragmented and fails to scale without gender-intelligent practices and policies embedded across the core of the institution. When institutionalized, gender intelligence allows FIs to diversify portfolios, expand market share, and unlock historically underserved markets. These practices support the future of smart, strategic, and sustainable finance.

AI pre-summit 2026: People, planet, and progress shape Indonesia–India cooperation toward ethical AI and a safer digital future

21st January 2026, Jakarta: The official pre-summit event of the AI Impact Summit 2026, titled “People, Planet, Progress: The India–Indonesia Dialogue on Inclusive AI,” convened in Jakarta. The event was the result of a collaborative effort by MSC (MicroSave Consulting), the Embassy of India in Jakarta, the India Indonesia Chamber of Commerce (IndCham), and India’s Women Entrepreneurship Platform (WEP) under the NITI Aayog.

The event brought together several participants, such as senior government officials, industry leaders, global development partners, and technology experts from both nations, to deepen cooperation on responsible, human-centric, and ethically governed artificial intelligence systems. This dialogue laid the foundation for the global summit in New Delhi.

The dialogue highlighted strong alignment between India and Indonesia’s national artificial intelligence (AI) priorities. India emphasizes responsible innovation, alongside multilingual and accessible AI technologies through the people, planet, and progress framework, which prioritizes the integration of these tools with digital public infrastructure to deliver equitable access at scale.

Indonesia’s National AI Strategy (2020–2045) and its AI ethics framework highlight trust, transparency, talent development, and accountability to integrate AI across key national priority sectors. These sectors include health, governance, education, food security, and mobility. Both nations recognize AI as a transformative enabler to strengthen public service delivery, expand economic opportunity, and enhance resilience for women, informal workers, as well as micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs).

In his opening remarks, the Ambassador of India to Indonesia, Sandeep Chakravorty, emphasized that AI plays a strategic role in advancing social good, including improving public services, expanding financial inclusion, and strengthening needs-based social protection.

“This dialogue is not only about technology, but also about concrete steps to build an inclusive and sustainable AI ecosystem ahead of the India–AI Impacts Summit 2026 in New Delhi,” he said. While India can share its human expertise and technological advancements in digital space, Indonesia can support it with its network capacities.

In the same vein, Vikram Sinha, President Director & CEO of Indosat Ooredoo Hutchison, underscored the importance of cross-industry collaboration as a key enabler for translating AI policy visions into tangible economic impact. He views AI system interoperability, Indonesia–India business partnerships, and the strengthening of startup and MSME ecosystems as critical foundations to ensure that AI development goes beyond technological innovation and drives inclusive, efficient, and competitive economic growth, with human learning being in the lead, not just in the loop.

Meanwhile, the Vice Minister of Communication and Digital Affairs (KOMDIGI), Nezar Patria, highlighted that the partnership between Indonesia and India presents significant opportunities for the development of artificial intelligence oriented toward the public interest.

“Digital economic growth in both countries presents a strategic opportunity to harness AI in a safe, trustworthy, and human-centered manner to address public challenges, ranging from financial inclusion to climate resilience,” he said.

He added that strengthening governance frameworks and investing in foundational AI infrastructure are key to ensuring that AI innovation develops inclusively and delivers broad-based benefits to society. He highlighted the scope of closer cooperation in this area exists in the MoU signed between India and Indonesia during Prabowo’s visit to India in early 2025 for which he looks forward to his visit to Delhi for the upcoming summit.

Anna Roy, Programme Director and Mission Director at the Women Entrepreneurship Platform (WEP), highlighted how India seeks to empower women-led innovation in AI. She noted that inclusive AI ecosystems must ensure equitable access to skills, tools, and opportunities for women and young innovators across the region.

The event also featured strategic panel discussions with policymakers, private sector innovators, philanthropic institutions, and multilateral development organizations to exchange perspectives on inclusive AI. The first panel explored how South–South collaboration can strengthen AI innovation ecosystems through interoperable data frameworks, digital public goods, and deeper research–industry linkages. The second panel examined AI’s potential to empower the workforce and MSMEs, which highlights the integration of AI with reskilling pathways, digital inclusion strategies, and social protection systems.

In support of this, Andianto Haryoko, Director of Infrastructure, Digital Ecosystem, and Digital Security at the Ministry of National Development Planning (Bappenas), emphasized that AI and digital transformation are key enablers of Indonesia’s medium- and long-term development agendas. She noted that “AI must support our economic transformation and strengthen public service delivery. Our priority is to ensure that digital progress benefits all Indonesians, especially women, informal workers, and MSMEs who form the backbone of our economy.”

Andianto highlighted the importance of data integration, harmonized digital public services, talent development, and support for domestic innovation to ensure that AI contributes to inclusive and equitable national growth.

The event concluded with closing remarks from Grace Retnowati, Partner and Country Head of Southeast Asia at MSC. As a member of the Alliance for Inclusive AI, MSC (MicroSave Consulting) brings practice-based experience in advancing the responsible adoption of AI, aligned with the event’s emphasis on people-centred innovation and sustainable impact. She emphasized MSC’s commitment to human-centered and inclusive AI across the region: “AI’s true value emerges when it advances human dignity, expands opportunity, and lifts communities. MSC will continue to collaborate with governments and industry actors to ensure AI systems are responsibly designed and broadly accessible.”

The pre-summit event highlighted a critical priority. AI systems require advanced digital capabilities, but they must also be equitable, transparent, gender-responsive, and aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals. These insights and collaborations developed in Jakarta will directly support the AI Impact Summit 2026 in New Delhi. As a result, concrete commitments and collaborative frameworks will be formalized to advance AI that works for people, planet, and progress.

This was first published in “Indian Embassy Jakarta” on 21st January 2026.

The Quiet Crisis of Care in a Young and Ageing India

I am often struck by the extraordinary demographic moment we are living through in India. We may be the only country where we are substantially young and substantially old at the same time. Sixty-five percent of our population is below the age of 35, while approximately 150 million people, close to ten percent of our population, are above the age of 60. This is not a distant future, it is the India we inhabit today, and it compels us to think urgently and deeply about the systems and structures that hold families and communities together.

There are several trends that demand our immediate attention. One of the most significant is the rapid rise of nuclear households, driven largely by urbanization and changing economic realities. Nuclear families accounted for around 50% of Indian households in 2022, up from 34% in 2008, signaling a significant shift in family structures across both large and small cities. With this shift, the social infrastructure of care that once sustained generations is diminishing at an unprecedented pace. Traditional forms of caregiving, which were embedded in extended family arrangements and community culture, are weakening, leaving individuals and families with fewer sources of support.

Life expectancy has increased dramatically, and many of us are now living into our eighties. Elderly women live even longer by three or four years on average. But health span is not keeping pace with lifespan. The quality of the years we gain depends on our physical health, our independence, our dignity, and our financial security. Recent data indicates that seventy-five percent of elderly people in India have one or more chronic illnesses, twenty percent face mental health struggles, five percent have experienced some form of abuse (physical, sexual, psychological, or financial) within their own homes, and only eighteen percent have any health insurance. These challenges are further intensified in rural areas, where sustained out-migration of younger family members has sharply reduced the availability of everyday care.

This is why I frame care as a continuum that stretches across childcare, eldercare, domestic work, and even animal care, particularly in rural economies where livestock defines livelihood. Across this continuum, the burden of care is disproportionately borne by women. Care responsibilities account for the exclusion of an estimated 53 per cent of women from India’s labour force. According to the government’s time-use survey, women spend between five to seven hours a day engaged in unpaid care work, the largest share of which is household labor. In many cases, entry into the workforce is not only constrained by supply of jobs but by the quality of work available. If decent and quality employment opportunities are not available for women, they may choose to stay home for their children or elders rather than accept low paid work. When care remains invisible and unsupported, women’s economic exclusion is not a failure of aspiration or a personal choice, they are economic and structural realities.

We are dealing with a huge care deficit, and its implications are social, economic, and moral. The care economy must be understood as a long-term priority. Care cannot remain a private matter, silently absorbed within families and largely by women. It is a public issue and a shared responsibility of the state, the market, and communities. We also have to consciously move away from phrasing “care” as a “burden”. Care makes us human and is an essential prerequisite for human capital to survive and thrive. Every one of us begins life needing care, and if we are fortunate to live long enough, we end life needing care again. In between these stages, we depend on care more than we often admit.

Care forms the very foundation of human capability and economic development. We must learn to see it not as expenditure but as investment. The single most important investment we can make is in the care of children, the elderly, and families who sustain our social fabric. When governments and markets invest in eldercare, they are investing in their own future, because every one of us is aging. When we support high-quality childcare, we create the conditions for a healthier, more capable generation. When workplaces genuinely support caregiving needs, they not only follow the law but strengthen their own wellbeing and productivity.

Families will always remain irreplaceable in care. No institutional model can replicate what family care provides in emotional depth and trust. But we must build systems that offer dignified, high-quality, and affordable options for families who need supplementary care from outside support systems especially when economic insecurity is a reality for millions. We need multiple models, new imaginations, and pathways that help families balance paid and unpaid work without forcing impossible choices.

The question before us is profoundly simple: What kind of society do we want to grow old in and what choices are we making today to shape it? If we ignore care now, we will inherit a future marked by loneliness, inequity, and exhaustion. If we choose to value care, invest in it, and place it at the center of how we measure progress, we can build a society that is humane, dignified, and deeply connected.

And all of us must decide together—because the future we are building is the one we ourselves will inhabit.

This was first published in “Reimagining The Family” on 14th January 2026.