This report is drafted on behalf of the Nigeria Governance Forum (NGF) to assess the readiness of 37 Nigerian states to utilize the DPI approach in public service delivery. Following this, we developed state-specific roadmaps tailored to each state’s current DPI maturity to facilitate their inclusive digital transformation. This report reflects our year-long collaboration with Nigerian states, during which we identified strengths and weaknesses across digital identity systems, interoperable payment systems, data exchange platforms, and foundational connectivity infrastructure.

Connecting innovation, institutions, and the missing middle: Insights from the 2025 Nobel for building labs and market creation

A seismic shift emerged in how we view society and civilizational progress when Philippe Aghion, Peter Howitt, and Joel Mokyr received the 2025 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. The trio reminded the world that innovation results from deliberate design, not luck. Their collective work explains why societies grow when they enable new ideas to replace old ones. This process, and its dependencies, lies on entrepreneurs, innovators, and on institutions that learn, compete, and collaborate.

The Nobel Prize feels personal for those who are building innovation labs and market-creation programs. It validates the messy, iterative work to incorporate startups into bureaucracies, align funders and regulators, and turn pilots into real markets. It tells us that the job is to design systems that enable continuous innovation rather than to simply “do innovation.” From this research, we can draw three vital lessons that link with MSC’s work in the startup space under our Startup Innovation and Acceleration (SIA) team.

Lesson 1: Innovation requires institutions that learn: Joel Mokyr’s research shows that economic progress occurs when societies build institutions that value useful knowledge and share experiments, failures, and cumulative lessons rather than hiding them.

The Bihar Krishi digital platform embodies this spirit. Developed in collaboration with the Bihar Agriculture Department in India, Bihar Krishi is among MSC’s leading innovation-lab projects. It has unified 50-plus government programs and services for more than 750,000 smallholder farmers within 18 months of launch. The platform has transformed a state department into a living digital entity that continually learns and builds institutional muscle beyond technology. The department now has its own innovation cadence, which intends to expand toward 4 million farmers through AI-driven advisory, market linkage, and financial services modules.

Bihar Krishi offers three simple yet profound takeaways for any innovation lab.

The lab must capture lessons as deliberately as it funds experiments;

Every pilot should leave behind codified knowledge, whether templates, APIs, procurement notes, or data taxonomies, which reduces the cost of the next experiment;

Innovation without institutional memory is mere performance art.

Lesson 2: Creative destruction needs safe spaces to function: If we move to the work of Mokyr’s partners, Phillippe Aghion and Peter Howitt, the core idea of creative destruction can sound brutal. Yet, the essence of creative destruction is renewal. New ideas must be allowed to challenge the old, or progress stalls. For governments, banks, and large agencies, this is uncomfortable territory.

Yet, when we examine initiatives, such as the FPS Sahay program in India, we see a controlled pathway for responsible innovation. FPS Sahay enables fair price shop (FPS) entrepreneurs to access invoice-backed digital working-capital loans and allows FinTechs to pilot alternative approaches within a supervised setting. The platform is the brainchild of the Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI) and the Department of Food and Public Distribution, with technical support from MSC (MicroSave Consulting).

The FPS Sahay program carved new credit pathways for 60 entrepreneurs in the pilot phase. Post-pilot discussions are underway to explore the potential to scale to 500,000 microenterprises and create a policy pathway for embedded finance.

The lesson is that labs must make room for controlled disruption, which helps simplify onboarding for innovators, provides clear “go or no-go” decision gates, and includes honest sunset clauses. This structure enables pilot programs that do not work to end smoothly, and those that do work to scale quickly. Institutions need permission structures to let new programs replace old ones without fear.

Lesson 3: Markets require active engineering: Innovation fails when the ecosystem is unprepared to absorb it. Mokyr’s “useful knowledge” meets Aghion-Howitt’s “competition” only when markets, regulation, and capital align. This is the key logic of MSC’s SIA team’s market-creation stream, which works to design accelerators, challenge funds, and centers of excellence (CoEs). Together, these mechanisms serve as vehicles to engage with innovators, absorb new business models or systems of product and service delivery, shape demand, and unlock private investment around complex public problems.

The Financial Inclusion Lab (India), co-built with IIMA Ventures and MSC, exemplifies this approach. It brought 49 startups, mostly FinTechs, into the same room as regulators, investors, and banks, to translate sandbox pilots into investable ventures. Those startups went on to raise USD 250 million in follow-on capital and reach 45 million low-income customers.

The lab accelerates startups that engineer a market for inclusive finance, much akin to what the Nobel trio modeled theoretically.

The design rule is clear for innovation labs elsewhere. The priority is to build the ecosystem handholding, which includes regulatory dialogue, data interoperability, and blended-finance pools, before private markets can scale solutions. These three lessons inform the efforts of the SIA practice at MSC, which works on two interconnected fronts:

- Institutionalinnovation labs:We help governments, banks, and public programs create arm-length labs that change how they learn, procure, and deliver by testing solutions safely, working with startups, and building institutional capability.

- Market-creation programs (accelerators, challenge funds, andCoEs):These programs shape demand for new solutions in a sector. They allow institutions to engage with innovators, absorb new business models, and direct private capital toward complex public problems.

Institutional labs improve how a single institution learns and delivers. In contrast, market-creation programs establish the broader ecosystem conditions of demand, capital, and partnerships that individual labs cannot achieve on their own.

When these two fronts connect, institutional labs validate what works, while market-creation programs help scale these solutions. The resulting market signals feed back into labs with new data and partners. This feedback loop, what Nobel economists call cumulative innovation, is how experimentation grows into a system.

Why does it matter now?

Whether we discuss climate adaptation, farm productivity, or AI for public purposes, the challenge is not a shortage of ideas but rather a shortage of systems that allow ideas to survive in contact with reality.

As the Bihar Krishi Digital Platform digitizes agri-services, FPS Sahay rewires credit for microentrepreneurs, and Financial Inclusion Lab alumni expand access to digital finance. Together, these programs offer glimpses of the decade ahead. This future shows innovation anchored in institutions, scaled through markets, and continuously improved by ecosystem feedback. This is good economics and good governance that proves how creative destruction becomes constructive inclusion.

Today, institutions spend trillions yet innovate with decades-old capacity. In this scenario, MSC’s SIA practice has a clear mandate. Our mission is to build labs that turn experimentation into permanent capability and markets that make innovation inevitable. That is the heart of SIA’s mission and exactly what this year’s Nobel prize reminded us to keep doing.

The Intelligent Revenue Authority Readiness Report

This report evaluates the digital public infrastructure readiness of revenue authorities across Nigeria’s 36 states and the FCT using the Intelligent Revenue Authority (IRA) framework. It analyzes maturity across person-to-government, business-to-government, and government-to-government payment systems, highlighting significant variation in digital adoption. While some states demonstrate advanced integration, automation, and data use, many rely on manual processes and fragmented systems. The report proposes phased, state-specific roadmaps to strengthen interoperability, automation, digital governance, and human capacity, aiming to improve revenue mobilisation and service delivery.

Timely Wages, Trusted Payments: Smart Payments for Urban Livelihoods

Urban livelihoods in India are predominantly informal, leaving workers vulnerable to insecure employment and limited social protection. This vulnerability was starkly exposed during the COVID-19 pandemic, when millions of migrant and low-income urban workers faced sudden income losses. The Housing and Urban Development Department (H&UDD) of the Government of Odisha responded to this crisis by working with existing community networks to create mass employment opportunities for the urban poor, informal, and migrant laborers. While MUKTA provided a critical safety net, its effectiveness was undermined by severe delays in wage payments to beneficiaries. These challenges undermined the intended outcomes of MUKTA. They not only strained workers’ livelihoods but also resulted in weak fiscal accountability at the urban local body (ULB) and state levels.

To address these challenges, MSC, in partnership with the state government, designed and implemented a scalable Smart Payments Solution (SPS). The solution combined a digital program management platform, MUKTASoft, with a just-in-time funding system. MUKTASoft digitized every stage of scheme implementation using a rule-based smart payments engine. The JIT funding mechanism ensured that funds were released directly from the state treasury to beneficiaries’ bank accounts.

The pilot implementation of SPS delivered substantial results. Wage delays were reduced, approval times fell sharply, utilization certificate pendency dropped to zero, and overall fund management efficiency improved. Women SHG members also reported faster receipt of payments, reduced administrative burden, and greater financial independence. The success of the pilot led to the statewide rollout of SPS across all ULBs in Odisha. This case study demonstrates how smart payments, grounded in sound public financial management principles, can improve welfare delivery systems, and strengthen livelihood outcomes for urban informal workers at scale.

Performance over assets in Bangladesh’s credit reform

In this three-part series, we scrutinized the shift toward multiple credit bureaus for financial service providers (FSPs) in Bangladesh. The first part discussed the implications of the framework for multiple credit bureaus, while the second part focused on regulators and development partners (DPs). In this final part, we examine market incentives and global lessons that show how a multi-bureau system can drive financial inclusion on a large scale.

The multi-bureau reform enables Bangladesh to shift from a collateral- and relationship-based credit identity to a performance-based one. This change creates opportunities for MSMEs, informal workers, and new borrowers who previously struggled in the formal financial system.

Private credit bureaus can expand the basis to assess creditworthiness for these segments of borrowers, as they primarily assist borrowers without formal income documentation or collateral. While many low-income households and informal workers repay their debts reliably, their financial discipline remains hidden within single lenders.

Alternative data, such as mobile money transactions and utility payments, holds immense potential to serve such thin-file borrowers. However, the near-term priority for the regulator and the market must remain on standardizing and ensuring full-file reporting of traditional credit data from banks, MFIs, and cooperatives. Alternative data can only strengthen scoring after this core foundation becomes robust and reliable, which means its full utility is a second-stage integration.

When bureaus participate in the credit ecosystem, they make repayment history portable across the financial sector. This portability allows lenders to evaluate borrowers based on their repayment track record rather than their physical assets. The transition enables gradual increases in loan size over time. Eventually, as borrowers build their credit profiles, they can then move from microfinance products to formal enterprise loans. This progression represents a fundamental shift in how financial institutions view the creditworthiness of customers in emerging markets.

Most lenders globally treat bureau scores as only a first-level filter in their decision process. This initial screening may restrict credit access for borrowers with limited credit histories and thin credit files for lenders to assess their creditworthiness accurately. Still, borrowers typically can access more credit over time, as their data becomes richer and more comprehensive. The challenge lies in how consistently the market applies these scores and filters rather than rely solely on credit scores.

For Bangladesh, consistency has emerged as a more critical issue as the country moves forward with its reforms. The Bangladesh Bank issued letters of intent (LoI) to five companies to form credit bureaus: Creditinfobd, TransUnion, bKash Credit, First National Credit, and City Credit. Later, TransUnion and bKash announced that they would establish a joint company, which reduced the number of credit bureaus to four. These four private bureaus will now enter the market with different methodologies.

Consistency will be paramount for the market to trust this multi-bureau system. This depends on three core elements:

- Data definitions: The exact borrower attributes being captured and reported, such as loan type, repayment status, and delinquency buckets;

- Weighting logic: How different variables, such as repayment behavior, outstanding exposure, and frequency of defaults, are weighted within the score;

- Score calibration: How raw risk estimates are translated into standardized score ranges so that scores are comparable and predictive.

If the scoring models diverge significantly, lenders may over-rely on the most conservative scores available. They may also avoid bureau insights altogether and return to traditional assessment methods, which include requiring collateral, relying solely on fixed income in the form of pay stubs, or using manual relationship-based assessments. This outcome would limit the benefits for low-income and MSME borrowers who need these new pathways the most.

The Bangladesh Bank maintains direct oversight over the scoring process to prevent this fragmentation. These regulatory safeguards are central to consistency and consumer trust:

- Mandatory model approval: The central bank requires mandatory model approval for all credit bureau scoring methodologies.

- Non-discriminatory scoring: Guidelines explicitly prohibit the collection of sensitive attributes, such as political affiliation or religious beliefs, to prevent bias.

- Score as a filter: A critical protection mandates that lenders cannot rely solely on a bureau’s score; it must be used as only one structured input among others in the credit decision process.

The impact of this bureau reform also depends on the digital readiness of lenders across the market. Smaller FSPs with manual data workflows struggle with consistency and timeliness. Borrowers cannot fully use their reputation capital when technical limitations obscure credit history. The infrastructure must support seamless data exchange to realize the reform’s full potential.

True inclusion requires the definition of creditworthiness to expand beyond formal loan repayment data. The system must incorporate behavioral indicators, such as mobile money patterns, utility payments, and savings behavior. These indicators accurately reflect financial reliability in informal settings where traditional credit histories are absent. The challenge lies in how bureaus translate diverse data sources into robust models that lenders will trust.

Pakistan offers relevant examples through platforms, such as Jumo and JazzCash, which use mobile money transaction patterns to determine internal credit scores. Bangladesh can adopt similar approaches where bureaus recognize financial progress through non-traditional indicators.

Similarly, Africa offers valuable lessons from credit bureau transitions. If participation remains uneven, a “two-speed” credit market emerges. Global lessons, particularly from Tanzania and Kenya, demonstrate that when reporting is mandatory only for banks and not fully integrated by MFIs, credit discipline improves in the formal sector. However, this change merely shifts over-indebtedness to the segments that remain unreported. This is the key risk for Bangladesh in terms of financial stability.

If MFIs and cooperatives lag in both reporting and the use of bureau data, credit risk migrates into unregulated segments. Bangladesh must address this immediately to ensure the reform strengthens the financial sector.

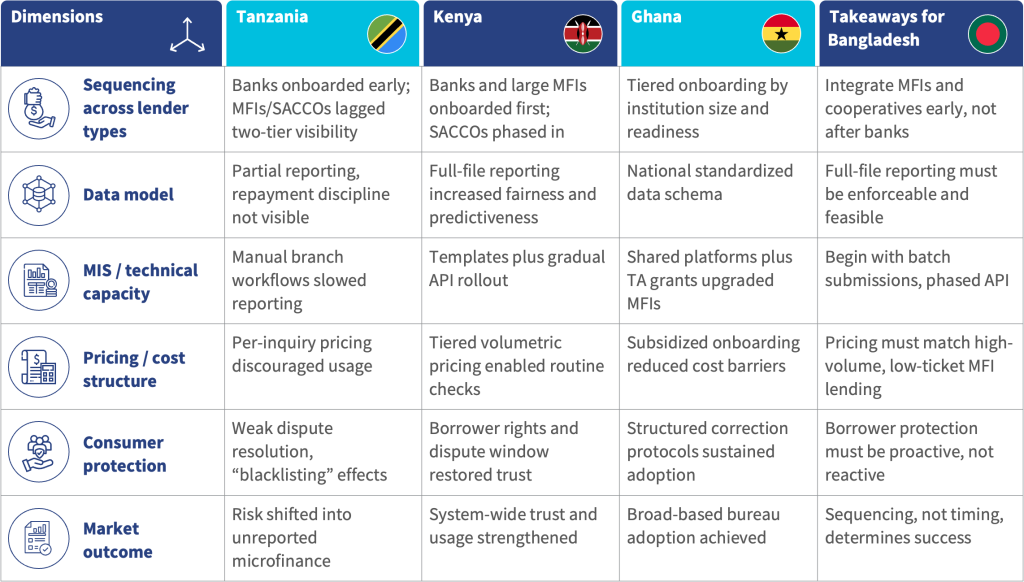

Tanzania and Kenya saw banks adopt bureaus early, but microfinance institutions (MFIs) and savings and credit cooperative organizations (SACCOs) lagged significantly. This gap shifted over-indebtedness problems to unreported segments. Meanwhile, Ghana shows that broad visibility across all lender types is achievable. The country sequenced onboarding by institutional capacity and provided smaller lenders with dedicated technical support.

Bangladesh must integrate MFIs and cooperatives early in the implementation process to prevent a two-tier system where only formal banks benefit from shared data. The integration should follow a phased approach that starts with standardized batch submissions. The system can transition to real-time API checks as capacity improves.

Comparative lessons from the implementation of credit bureaus in Africa

Source: Created by MSC with inputs from Maxwell Investment Group and Zeeh

Credit bureau pricing structures must support high-volume, small-ticket transactions that characterize MSME and microfinance markets. Per-inquiry fees discourage routine use by MFIs and merchant lenders, which operate on thin margins. Volume-based or institutional flat-rate models support regular bureau checks without prohibitive cost barriers.

Beyond access fees, bureaus must provide decision-ready intelligence over raw data dumps. They should deliver standardized scorecards and risk dashboards that help lenders apply bureau information meaningfully in their underwriting processes. Many smaller lenders lack the technical capacity to build proprietary models from scratch.

Regulatory authorities and governments must establish consumer protection frameworks alongside technical infrastructure. Kenya’s experience shows that negative-only systems can entrench exclusion rapidly when borrowers cannot recover from mistakes. Borrowers must have clear rights to access, dispute, and correct their records. Improved data infrastructure alone will not automatically change credit decisions in the market. FSPs must treat bureau information as a primary input that actively influences loan amounts, interest rates, and repayment terms.

A major tension in the transition is between regulatory enforcement (reporting data) and voluntary participation (using data). Specifically for MFIs and high-volume digital lenders, cost and workflow friction often drive this tension. If bureau access is priced per inquiry or per user, institutions may report data to comply with regulations but limit bureau checks in practice, which would render the bureau a passive repository rather than a live decision-making tool.

Regulators must, therefore, establish a supportive pricing model, such as volume-based or institutional pricing, which makes high-frequency, low-cost access viable for all lender segments to ensure lenders use the bureau in underwriting.

Regulators, DPs, and FSPs must prioritize three critical elements in their execution:

- Ensure broad participation across all lender types from the start;

- Establish strong data standardization that creates consistency across bureaus;

- Enforce proactive consumer protection measures to build trust in the system.

The success of Bangladesh’s multi-bureau system depends on operational choices and specific implementation plans, rather than broad policy goals. The sequence of implementation matters more than the speed of rollout. If made sensibly, these coordinated efforts will unlock the full potential of Bangladesh’s credit bureau reform and carve pathways to financial inclusion for people who have been excluded for far too long.

Interoperability in Bangladesh: The Stakes, the setbacks, and the way ahead

Despite regulatory readiness and technical infrastructure, key providers remain hesitant to adopt interoperability. Addressing commercial, operational, and governance gaps now is essential for nationwide uptake

Interoperability is widely acknowledged as one of the most powerful enablers of digital finance. When customers can send, receive, and use money across various providers—such as banks, payment system providers, wallets, and cards—the payments ecosystem becomes faster, more convenient, and potentially cheaper.

The World Bank and CPMI’s Principles for Financial Inclusion (PAFI) emphasise that interoperability increases competition, reduces fixed infrastructure costs, enables economies of scale, and significantly enhances customer convenience.

Globally, interoperable systems—from India’s UPI to Tanzania’s mobile-money rails—have demonstrated that shared infrastructure significantly increases transaction volumes, lowers marginal costs, and fosters innovation. Interoperability also strengthens merchant acceptance and makes digital ecosystems “sticky”, reducing customer dropout, increasing digital uptake, and improving trust.

Yet Bangladesh did not have interoperability for years, and relied on bilateral arrangements

Despite having one of the world’s most dynamic mobile-money sectors, Bangladesh operated without true interoperability for more than a decade. Before 2019, the market relied heavily on bilateral arrangements such as bank-to-wallet transfers through individualised agreements (e.g. BRAC–Rocket partnerships), card-to-wallet top-ups using specific bilateral integrations (e.g. bKash–Mastercard), and wallet-to-wallet transactions between select partner providers, rather than across the whole ecosystem.

This bilateral approach had three consequences:

a) high integration costs for each new partnership;

b) no uniform pricing, leading to market distortion;

c) digital silos, where each large provider captured its own customer base and ecosystem.

Given the dominance of leading MFS providers such as bKash, Nagad and Rocket—and the associated float income, agent-network investments, and branding advantages—there was little commercial incentive for them to open up to competitors voluntarily.

How things have changed

To address these structural barriers, the UK-funded Business Finance for the Poor in Bangladesh (BFP-B) programme undertook extensive technical work on interoperability from 2017 to 2020.

BFP-B concluded that Bangladesh could unlock enormous value if it shifted from bilateral, provider-led integrations to a switch-based, rules-driven interoperable ecosystem under Bangladesh Bank.

Under the BFP-B programme, MSC developed a comprehensive framework to support the Bangladesh Bank in the rollout of interoperable digital financial services. The operational guidelines defined key use cases including wallet-to-wallet, bank-to-wallet, card-to-wallet, PSP-to-wallet, and merchant payments and outlined a phased, switch-based implementation sequence with real-time settlement through the National Payment Switch Bangladesh (NPSB).

These guidelines were comprehensive, detailed, and technically robust—yet adoption was limited at the time for various reasons, including a lack of provider participation.

After more than five years, Bangladesh Bank has enabled interoperability through NPSB

Recently, Bangladesh Bank formally enabled account-to-account interoperability through NPSB, updating the regulatory framework to include banks, mobile financial services, microfinance institutions, and payment service operators. The switch now supports real-time clearing and multi-party settlement. This marks a significant regulatory commitment as NPSB rules are upgraded, settlement processes standardised, and technical processes established for providers to follow.

Despite regulatory readiness, the adoption of interoperability through NPSB has lagged. Providers question the commercial benefits as they face high integration and transition costs. They also argue that current interchange and fee structures do not offset lost float income and ongoing agent commissions, particularly for high-volume players with large agent networks. Many still doubt NPSB’s uptime, message integrity, fraud controls, and real-time-payments performance, and may hesitate to integrate until reliability at scale is demonstrated. Integrating with the central switch also requires significant technological upgrades, testing, and reconciliation changes, which weigh heavily on smaller or legacy institutions. Unresolved questions on SLAs, liability, AML/CFT, and interoperable pricing can further delay decisions and the onboarding of providers onto NPSB.

What can now be done to resolve concerns and bring large providers on board?

For successful uptake of interoperability, four specific actions—based on our experience—are necessary:

Reset the commercial model through a structured, transparent interchange framework: A well-designed pricing structure is key to successful interoperability. It must incentivise players to cover the costs of managing payment infrastructure, fraud prevention, and customer management and servicing. In Bangladesh, major players will also consider the impact on float income, transactional revenues, and distribution expenses before fully embracing interoperability.

Conversely, customers generally expect little to no cost for digital payments, as cash is considered “free”.

To address this, Bangladesh Bank may consider:

- Publishing a long-term roadmap or vision, to be reviewed annually

- Establishing a high-powered steering group comprising major players as well as smaller players and think-tanks to determine the fee and incentive structure

- Allowing temporary transition incentives for providers with large distribution networks

This mirrors strategies from Brazil (PIX pricing standards) and Pakistan (regulated 1Link pricing).

Implement a formal phase-wise onboarding model with readiness audits

A five-phase rollout sequence is recommended to give providers adequate time to prepare and integrate their systems, ensuring a steady adoption of interoperability.

This phased approach is akin to building a payment highway: Phase 1 starts by connecting the two biggest cities (MFS wallets), where traffic is densest. Phase 2 connects these cities to the national rail network (banks), already established on the switch. Subsequent phases handle smaller connections (cards, PSPs) and specialised infrastructure (merchants/QR codes), ensuring the system prioritises high-volume traffic before being overwhelmed by complexity.

Bangladesh Bank can also adopt a readiness-audit model similar to Kenya’s PesaLink, ensuring that each provider meets minimum requirements such as real-time-settlement capability, cybersecurity capacity, fraud-monitoring systems, system redundancy, and uptime before onboarding. These strict audits ensure providers are fully prepared before joining the “highway”.

Strengthen and enforce dispute-resolution and AML frameworks: Effective interoperability requires a robust, regulator-led dispute-resolution framework to manage the risk of errors, fraud, and customer harm that arise from cross-network transactions. Stakeholders expect Bangladesh Bank to establish fast, transparent processes—with clear turnaround times, dedicated monitoring teams, mandatory provider cooperation, and digital logbooks of disputes. Typical TATs vary: technical timeouts can be resolved within minutes, whereas cases involving the wrong recipient may take several working days. Providers must freeze disputed funds, act in good faith during reversals, and maintain teams capable of resolving issues quickly to safeguard customer trust.

Interoperability also increases AML/CFT and fraud-related vulnerabilities, demanding strict compliance and oversight. All participating entities must follow the Money Laundering Prevention Act, Anti-Terrorism Act and BFIU guidelines; ensure robust and regularly updated KYC practices; and report suspicious or fraudulent activity immediately. Strengthened internal controls, clear governance roles, and risk-mitigation protocols are essential to protect the ecosystem and maintain system integrity as digital financial services become increasingly interconnected.

Phased onboarding and regulatory concessions: Interoperability introduces significant integration and compliance costs, especially for newer or smaller providers who must upgrade systems, hire technical staff, and strengthen their capacity for real-time payments. Similar challenges were seen in Kenya, where smaller banks struggled with capital-intensive upgrades during the PesaLink rollout, underscoring the need for phased onboarding and regulatory support.

International experience shows that temporary regulatory concessions can accelerate adoption and create a more level playing field. For example, Jordan’s JOMOPAY waived all provider fees, and providers themselves agreed to forgo interchange for the first two years, allowing the ecosystem to stabilise before cost-recovery mechanisms were introduced. Drawing on these lessons, Bangladesh Bank can promote integration testing through the central sandbox and waive switch and interchange fees for a defined period.

To support providers and customers in adopting interoperability, Bangladesh Bank and the Government can explicitly support zero-switch fees during the early stages.

Conclusion

Interoperability aims to address a significant economic challenge, extending far beyond a technical project. The BFP-B programme outlined operational and pricing options; Mojaloop now provides the technical rails. What is required now is coordinated execution: regulators setting clear, fair rules and timelines; dominant providers accepting temporary concessions in the interests of long-term market expansion; smaller players committing to strong operational standards; and donors and partners financing transition costs and technical assistance.

When each stakeholder plays their part—regulators guaranteeing a level playing field, market leaders managing migration responsibly, and development partners de-risking initial costs—interoperability will move from pilots and conferences to everyday transactions that lower costs and broaden access for millions.

Bangladesh can finally achieve interoperable digital payments—unlocking enormous value across households, MSMEs, government services, and the broader digital economy.

This was first published on tbsnews on 10 December, 2025