The Cambridge Analytica scandal of 2018 rocked the world and grabbed headlines as one of the most massive data privacy breaches ever. Cambridge Analytica accessed data from millions of Facebook users without explicit consent and used it for targeted political advertising. The breach stemmed from a personality quiz app that collected data from both users and their Facebook friends. And the numbers were shocking—the breach impacted up to 87 million people.

India’s new Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act intends to prevent data privacy breaches such as this. The DPDP Act was designed to counteract such unauthorized data collection and misuse, with strict consent and user rights provisions. It holds promise to bolster our digital security framework and ensure citizens’ privacy.

Over the past years, India has sought to build this system through expert discussions, reports, and the introduction of two earlier versions of the bill in 2019 and 2022. The Indian parliament approved the DPDP Bill in 2023, six years after the important case of Justice K.S. Puttaswamy v Union of India. In the case, India’s Supreme Court established the right to privacy, including personal data protection, as a fundamental right under the Indian Constitution’s “right to life.” The Supreme Court, comprising nine judges, recommended that the Indian Government establish a well-structured system to safeguard personal data.

This blog outlines the key provisions of the DPDP Act and the exemptions granted to various entities:

Scope of DPDP: The DPDP Act addresses several aspects, much like the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation. It broadly defines “personal data” to encompass various types of information about individuals. Furthermore, this Act applies to all entities that handle personal data, regardless of their size or whether they are private.

Purpose limitation: The DPDP law sets clear guidelines for the online use of personal data. It permits the use of this data only for specific reasons. The data must be erased once those reasons are fulfilled. Additionally, individuals have rights regarding their personal data. They are entitled to be informed about its use, access it, and request its deletion.

Establishment of Data Protection Board: The Data Protection Board plays a significant role to ensure the proper implementation and enforcement of data protection regulations. The board serves as a regulatory authority that oversees and supervises the protection of personal data in the country. Its key roles and responsibilities will include regulation and oversight, data audits and assessments, handling and complaints, research and development, and penalties.

Additional responsibilities for significant data fiduciaries: The DPDP Act empowers the government to label certain companies as “significant data fiduciaries” (SDFs). This categorization of SDFs will be based on factors, such as the volume and sensitivity of data they handle and the potential risks to the country. When companies are designated SDFs, they have increased responsibilities. One important responsibility is to assign a Data Protection Officer (DPO) who works in India. This person is the contact for complaints. SDFs must have an independent data auditor who ensures compliance with the DPDP Act and evaluates their data protection measures regularly.

Data transfers: The DPDP Act currently does not restrict the transfer of personal data outside India. Instead of defaulting to limitations, the Act assumes that data transfers are permissible unless the government specifically restricts transfers to certain countries or imposes other limitations. The Act does not provide clear criteria to impose such restrictions. Additionally, the DPDP Act clarifies that it will not change any existing data localization requirements.

Consent management: The DPDP Act requires that consent for data processing be “clear, specific, informed, and unequivocal.” Companies (data fiduciaries) must use personal information only for lawful purposes. They can use this data only with the individual’s (data subject’s) permission or for a justified reason.

Companies must use personal data exclusively for the purpose they inform the individual about. If they want to use it for a different purpose, they need to seek permission again. This ensures companies cannot obtain blanket approvals for multiple uses. Individuals can decline data use at any point, and rejection should be as straightforward as consent.

If someone opts out, their data must be deleted unless a specific law mandates its retention. The DPDP Act would allow individuals to grant, review or deny data use through a “Consent Manager” which will be registered with the data protection board. Consent Managers are tasked to ensure compliance and manage individuals’ data preferences.

Grievance resolution: The DPDP also allows people to seek grievance resolution, which means the company should provide an easy way to complain if customers feel their data was shared or processed without consent. The law does not specify the turnaround time for companies to respond to complaints. This decision will be made through separate rules, and various companies may have different timeframes. The DPDP gives customers the right to “appoint a nominee,” which allows individuals to select someone to act on their behalf if they cannot do so themselves.

Fine and penalty: The DPDP Act removes section 43 A of the IT Act, 2000, which provides for compensation if a company leaks an individual’s sensitive personal data or information. DPDP imposes fines on entities, including companies, banks, and even government data handling agencies, if they process citizens’ online data beyond the lawful purpose. These organizations can only use citizens’ online data for “legal reasons.” If they break the rules, they could face penalties that range from INR 50 crore to INR 250 crore (USD 6 million to USD 30.2 million), and their platform might be blocked.

The DPDP outlines specific responsibilities for users. Individuals must not impersonate others when they provide personal information, not omit crucial details when they submit personal data for government documents, and refrain from false or trivial complaints. Failure to adhere to these responsibilities may lead to fines up to INR 10,000 (up to USD 120).

Data protection for minors: The DPDP Act establishes important responsibilities on how to handle children’s personal data. It defines “children” as anyone younger than 18 years. The Act mandates that companies that handle data cannot process children’s data in a way that might harm their well-being. The Act also makes it illegal for companies that handle data to track or monitor children’s behavior or show them specific ads.

Exemptions: The law has some exceptions for government entities and includes specific exceptions. For example, the government is permitted activities related to national security, relationships with other countries, public order, and those that prevent crime. The law also says that Indian companies do not have to follow some important rules, such as giving people the right to see or delete their data if they handle data of people from outside India and have a contract with a foreign company. These Indian companies mainly have to focus on keeping the data secure. Personal data processed for research, archiving, or statistical purposes will also be exempted.

Significantly, the Act does not distinguish between sensitive and non-sensitive personal data and does not limit processing data outside the country unless the new rules identify specific restricted areas.

Conclusion

The DPDP Act is a concise document that uses simple words and illustrations to explain the provisions. This is a big change from the long and complicated ways data protection laws have usually been written. The DPDP represents a major effort to enhance online privacy and ensure data security in India. It intends to transform the privacy domain by emphasizing transparency, explicit consent, data minimization, and adherence to usage restrictions. Companies must allocate resources to understand and implement the DPDP Act’s provisions and anticipate associated compliance costs.

Companies can navigate the new regulations more effectively by adapting to these changes. While both houses of the parliament have approved the DPDP Bill, its specific rules will become clearer once it is enacted. This will occur when the government declares the official date for the law’s enforcement.

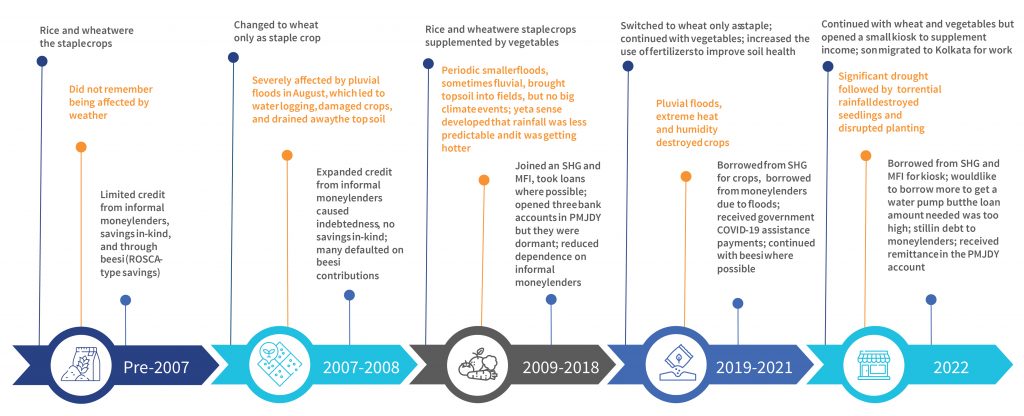

Each year after the harvest, the family stored about half of the harvested crops—primarily rice in those days—to meet their consumption needs. They would sell the rest and invest the money in livestock, although they also hid away some money in clay pots around the household. Krishna Lal’s wife, Devi, saved small amounts through her beesi, a savings club that pays out to one of its members each monthly round. She would usually use the proceeds to buy household utensils. She also squirreled away small amounts without Krishna Lal’s knowledge—and used these secret funds to buy treats for her son, Abhishek, and daughter, Preeti.

Each year after the harvest, the family stored about half of the harvested crops—primarily rice in those days—to meet their consumption needs. They would sell the rest and invest the money in livestock, although they also hid away some money in clay pots around the household. Krishna Lal’s wife, Devi, saved small amounts through her beesi, a savings club that pays out to one of its members each monthly round. She would usually use the proceeds to buy household utensils. She also squirreled away small amounts without Krishna Lal’s knowledge—and used these secret funds to buy treats for her son, Abhishek, and daughter, Preeti. In 2019 and 2021, the floods returned—with a vengeance—and Krishna Lal found out that he was not as resilient as he had believed. During these floods, he stopped growing rice and was focusing on wheat, which could be planted once flood waters recede in September or October and commanded higher prices in the market. But he started to worry about how much fertilizer he had to use to maintain output levels. He was also worried by the weather. May to July was unbearably hot and rains evaded their village until the end of July—he was unsure when to plant his rice seeds. Then it rained in a way he had never seen before. Within days, floods were rolling through his fields and then the village itself once again. It was like 2007 or worse. He was back to borrowing from moneylenders to keep food on the family table. Furthermore, the increased heat and humidity meant that his vegetables were infested with pests. Farming was no longer enough to finance his family’s needs—they had to think of ways to earn more.

In 2019 and 2021, the floods returned—with a vengeance—and Krishna Lal found out that he was not as resilient as he had believed. During these floods, he stopped growing rice and was focusing on wheat, which could be planted once flood waters recede in September or October and commanded higher prices in the market. But he started to worry about how much fertilizer he had to use to maintain output levels. He was also worried by the weather. May to July was unbearably hot and rains evaded their village until the end of July—he was unsure when to plant his rice seeds. Then it rained in a way he had never seen before. Within days, floods were rolling through his fields and then the village itself once again. It was like 2007 or worse. He was back to borrowing from moneylenders to keep food on the family table. Furthermore, the increased heat and humidity meant that his vegetables were infested with pests. Farming was no longer enough to finance his family’s needs—they had to think of ways to earn more. However, despite the small earnings from the kiosk and Abhishek’s intermittent remittances, the family still struggled to make ends meet. Krishna Lal had for many years dreamed of buying a water pump to irrigate his fields in times of drought and thus increase his yields. While the opportunity, and need, for this climate adaptation were stark, no one would lend him the large sum money he needed for this crucial piece of equipment. In 2022, he could really have used the pump as a merciless drought ravaged his crops from April to July. The heat was unbearable and the land was parched—it was useless to plant anything. And when the rains came in August, they were torrential…

However, despite the small earnings from the kiosk and Abhishek’s intermittent remittances, the family still struggled to make ends meet. Krishna Lal had for many years dreamed of buying a water pump to irrigate his fields in times of drought and thus increase his yields. While the opportunity, and need, for this climate adaptation were stark, no one would lend him the large sum money he needed for this crucial piece of equipment. In 2022, he could really have used the pump as a merciless drought ravaged his crops from April to July. The heat was unbearable and the land was parched—it was useless to plant anything. And when the rains came in August, they were torrential…