Bangladesh’s progress in the closure of 69% of its gender gap through the advancement of gender equality and women’s empowerment has been remarkable. Contributing factors include 20% female representation in parliament, improved healthcare access, and more than 50% secondary school enrollment of girls. Despite these achievements, financial inclusion remains a hurdle. Women’s access to mobile financial services and agent banking has proven to be crucial. Female agents can bridge the gender gap and provide tailored and trustworthy services. We must address their barriers and foster their participation in mainstream economic activities for economic empowerment.

Blog

Role of digital financial services in locally-led adaptation initiatives

MicroSave Consulting (MSC) is a boutique consulting firm that has, for 25 years, pushed the world towards meaningful financial, social, and economic inclusion. These podcast series are hosted by MSC for dedicated founders, start-ups, investors, and other stakeholders in the startup ecosystem. Through this bouquet of curated conversations around developments in the financial inclusion space, we offer insights and lessons based on our research and expertise.

In this podcast, Dennis Kuria and Judith Mwangoe, digital financial services (DFS) experts at MSC, discuss the role of digital financial services in locally-led adaptation initiatives.

Five things to know about the impact of extreme heat on MSMEs and their workers in India

Throughout April and into May 2024, extreme record-breaking heat led to severe impacts across most of Asia. A severe heatwave in north India during the last week of May led to deaths and cases of heatstroke. Several studies (here, and here) have shown that extreme heat in South Asia during the pre-monsoon period has grown more frequent and is strongly influenced by climate change. Extreme heat disproportionately impacts the lives and livelihoods of vulnerable people, particularly women and those who live in informal settlements in urban areas of the developing world.

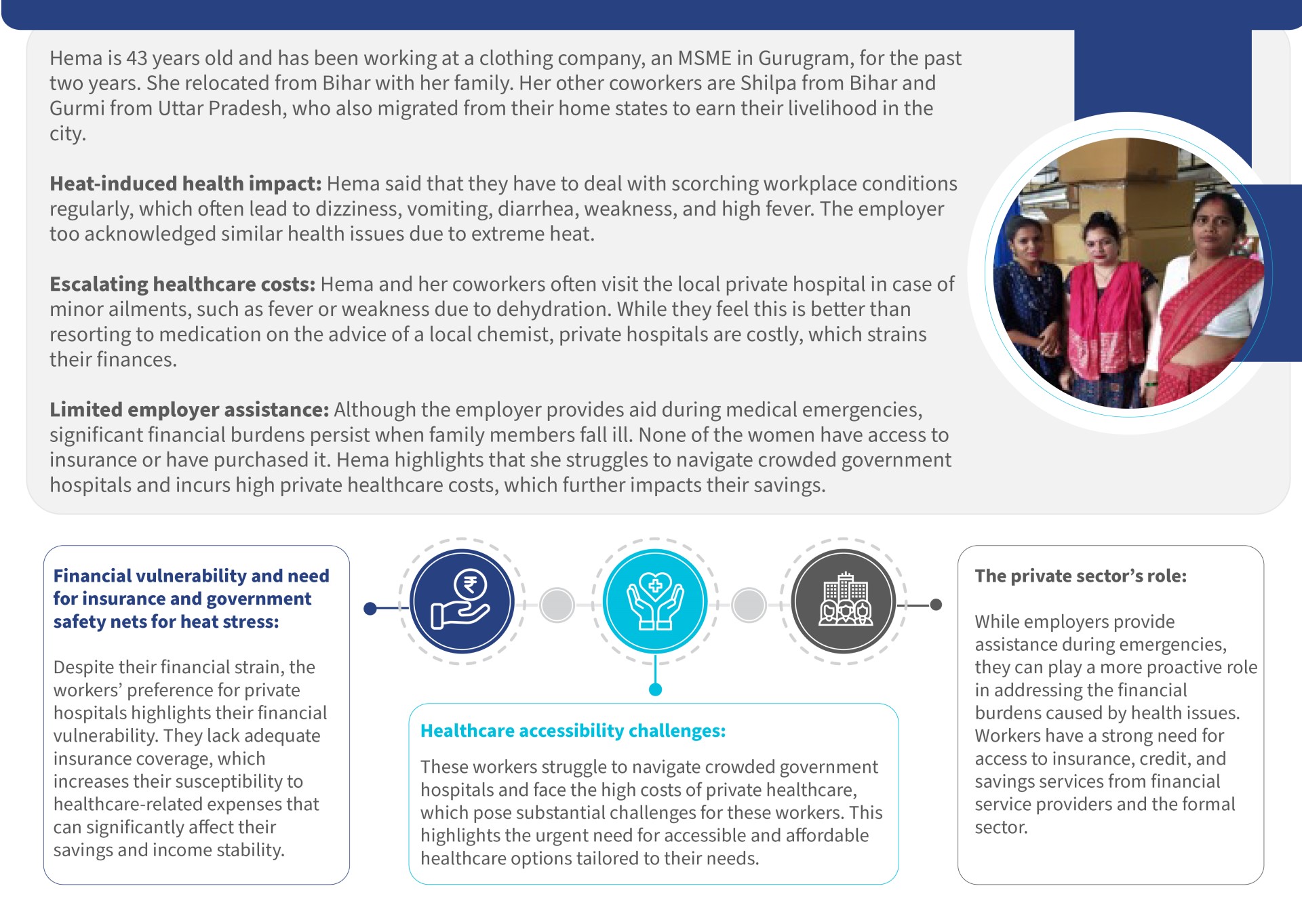

MSC conducted a study on the impact of extreme heat on micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) and their workers in India’s National Capital Region, which comprises New Delhi and surrounding areas. Here are the five things we learned from our research.

1) Extreme heat already affects workers’ health severely

Extreme heat poses a significant health risk to MSME workers and their families. Heatwaves can lead to increases in heat-related illnesses, such as heat exhaustion, heatstroke, and dehydration, and worsen preexisting conditions, such as respiratory and cardiovascular diseases. Vulnerable groups, such as older adults, infants, pregnant women, and outdoor workers, are particularly at risk.

Studies suggest that by 2100, an estimated 1.5 million additional lives in India may be lost annually due to climate-driven extreme heat. This alarming projection underscores the urgent need for effective health interventions and policies to protect workers from the adverse effects of extreme heat. However, insufficient data hinders proper analysis of extreme heat’s impact on vulnerable populations. Additional investments are needed to uncover impact data.

2) Extreme heat leads to economic losses and reduced productivity

The economic impact of extreme heat on MSMEs is already significant. High temperatures lead to productivity losses, reduced working hours, and increased operational costs. A study estimates that India already loses around 101 billion hours of work annually due to heat, equivalent to the work done by approximately 35 million people, each working an eight-hour day in a year. This loss translates to a potential GDP reduction of up to 4.5%, or approximately USD 150-250 billion by 2030.

Women, in particular, face a more significant burden due to unpaid domestic labor. As a result of extreme heat, women lose 19% of their paid working hours, while more than two-thirds of heat-related productivity losses stem from unpaid domestic tasks. This additional workload worsens gender inequalities and highlights the need for gender-responsive policies to address the unique challenges women face in the workforce.

3) Poor Infrastructure and high energy demand worsen the impact of extreme heat

The infrastructure in many MSME sectors is ill-equipped to handle rising temperatures. Poorly constructed workplaces and homes, inadequate cooling systems, and frequent power cuts exacerbate the impact of extreme heat. Workers who live in informal settlements without access to passive or active cooling solutions are particularly vulnerable.

We found that air conditioning and other cooling technologies significantly increase MSMEs’ energy consumption during the summer months, which strains the already unstable electrical grids. This high energy demand can lead to power outages, further increase costs for MSMEs, and diminish the capacity of healthcare facilities and other critical infrastructure to cope with heat-related challenges.

Sahil, an MSME owner in Gurugram, told MSC that “running air conditioning in summer is costly due to frequent power cuts. Generators or additional fuel costs an average of 1.5 -2 lakh (USD 1,700 to 2,300) monthly, which increases my operating costs drastically.” The lack of proper urban planning and green spaces in rapidly urbanizing areas also contributes to the urban heat island effect, which makes cities significantly warmer than surrounding rural areas.

4) Current coping strategies are inadequate for future heat challenges

Current coping strategies employed by MSMEs and their workers are inadequate to meet the scale of future challenges posed by extreme heat. Workers often resort to basic measures to cope with the heat. They drink more water, wear light clothing, cover roofs with wet quilts, seek shade under flyovers and trees, and take frequent breaks. Residents cook food multiple times to prevent spoilage, often during the early hours of the day. However, these strategies are insufficient to address the severe and prolonged heat stress expected in the coming years.

Employers have also made incremental changes, but these measures will fail to build long-term resilience. They take steps, such as providing employees with fans, coolers, and cool drinking water but they are not enough to deal with the impacts of heat waves and extreme heat. Employers, therefore, need to develop affordable and sustainable cooling solutions, improve workplace safety, and enhance access to financial products and services to manage heat-related risks for their employees.

5) Despite progress, MSMEs and their workers need additional and targeted support to increase their resilience to extreme heat

India has made notable strides in creating plans and policies to respond to the impacts of extreme heat, such as Heat Action Plans for cities, such as Delhi and states, the national Cooling Action Plan, and efforts to strengthen health systems to decrease heat-related mortality and morbidity. However, MSMEs and their workers require targeted support to increase awareness of the impacts of extreme heat and meet their financing needs to invest in sustainable cooling solutions. Workers who have high exposure to extreme heat and MSMEs that employ workers living in informal settlements, such as construction, need urgent support to reduce worker mortality and morbidity.

Figure 1: There is a lack of locally tailored and relevant support for MSMEs to respond to the impacts of extreme heat

MSC’s study on the effects of extreme heat on MSMEs and workers in Delhi NCR underscores the urgent need for comprehensive and targeted interventions to build their resilience against the escalating threat of extreme heat. These include the development of local programs that target MSMEs with the most at-risk workers, improve infrastructure, enhance access to financial products and services, and strengthen access to public services. By addressing these challenges, India can protect its workforce better, sustain economic growth, and ensure a more resilient future in the face of climate change.

The heat is on: Charting urban India’s course toward climate-resilient health

The alarming upward curve of heat

In 2023, our planet sizzled through its hottest year on record, with global average temperatures near the critical 1.5°C threshold against the pre-industrial baseline. Extreme heat events have become increasingly commonplace as they wreck lives and kill thousands. Dishearteningly, climate experts have already predicted 1.6 million deaths and ~USD 7.1 trillion in economic losses by 2050 due to extreme heat.

India has also been battling recurring extreme heat events, especially in urban settlements, creating heat islands in a sea of already rising temperatures. Projections indicate that by the year 2050, 300 million Indians, and by 2100, 600 million Indians will have a severely diminished quality of life due to excessive heat. The implications are already dire: exacerbated health risks, strained healthcare systems, and an increased mortality rate that can no longer be ignored.

Understanding the heatwave hazard

The rise in temperatures is an emergent health crisis. Extreme heat events directly correlate with spikes in heatstroke, dehydration, chronic diseases, and diminished cognitive performance. Urban areas, in particular, face a compounded risk due to the urban heat island (UHI) effect, where Indian cities become significantly warmer than their rural counterparts.

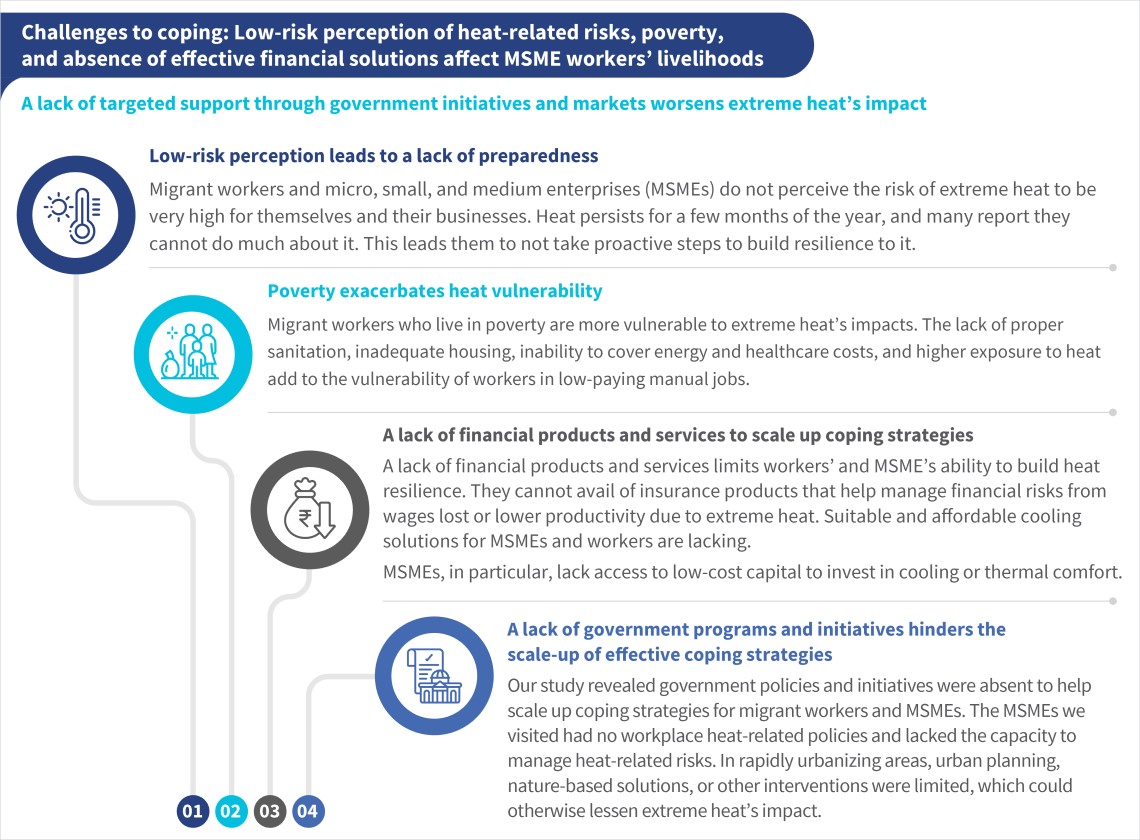

In a focused study, MSC uncovered the ground-level impacts of extreme heat on seven informal settlements and MSMEs in Delhi NCR. We identified four major challenges to cope with extreme heat.

The study strongly corroborated the World Health Organization’s (WHO) findings of severe heat-related symptoms—from debilitating cramps to life-threatening strokes. This is especially true, as humidity makes it nearly impossible for people to cool down. We also observed that gender inequalities became worse as they disproportionately affected women from low-income households. It led to a greater burden of work and adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as stillbirth.

The study also exposed the immense strain on our health systems due to heat. It leads to widespread emergencies, disrupts health services, swamps hospitals, and stretches medical professionals to their limits. This is not just uncomfortable—it is dangerous as it leads to a cascade of crises that affect the most vulnerable.

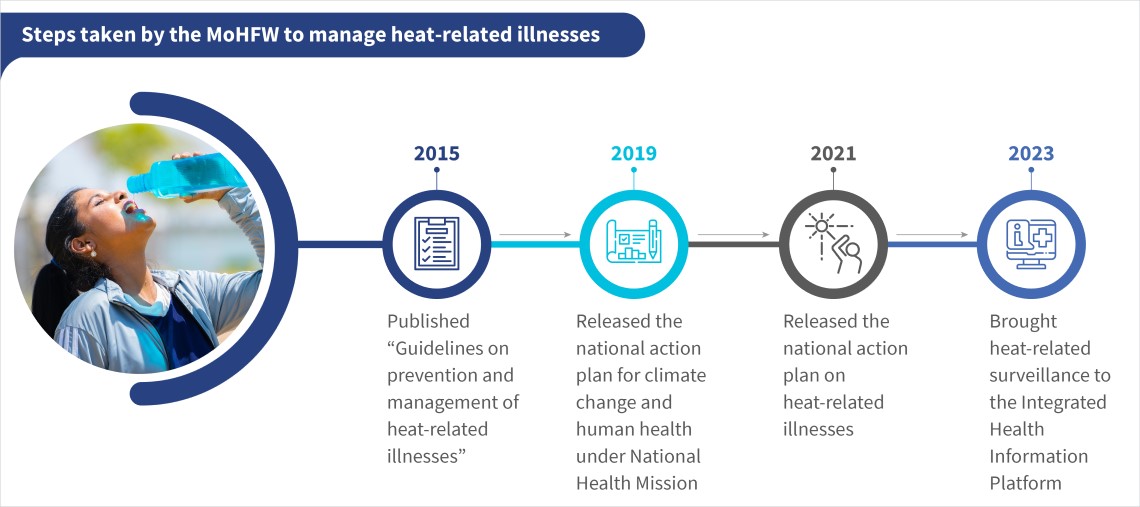

The Indian government’s role: From recognition to action

Over the past decade, India’s strategy against heat waves has evolved significantly. Sparked by a catastrophic heat wave in 2010 in Ahmedabad, which saw temperatures soar to 46.8°C and claimed more than 1,300 lives, India initiated its first heat action plan (HAP). This groundbreaking plan laid the foundation for early warnings, community engagement, and exposure reduction tactics. The National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) subsequently set forth comprehensive guidelines to encourage all heat wave-prone regions to adopt similar plans with a focus on early warnings, healthcare education, public awareness, and community partnerships.

Today, with HAPs active in 23 states and over 130 cities, India’s approach has become more refined and data-driven. The NDMA has expanded its focus to include detailed heatwave research, vulnerability assessments, city-specific hazard mapping, widespread educational initiatives, and state support mechanisms.

Simultaneously, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare has intensified its efforts to combat heat-related health impacts. It rolled out detailed guidelines and integrated heatwave, HRI (heat-related illnesses), and ARI (acute respiratory infections) data into the national Integrated Health Information Platform (IHIP) for more effective monitoring and response. However, data management at the local level, especially Urban Local Bodies, warrants improvement. Nevertheless, this shift toward a digital-first health surveillance system marks a significant advancement in how we track and address nationwide heatwave impacts.

Solutions to mitigate and adapt to heat-related illness

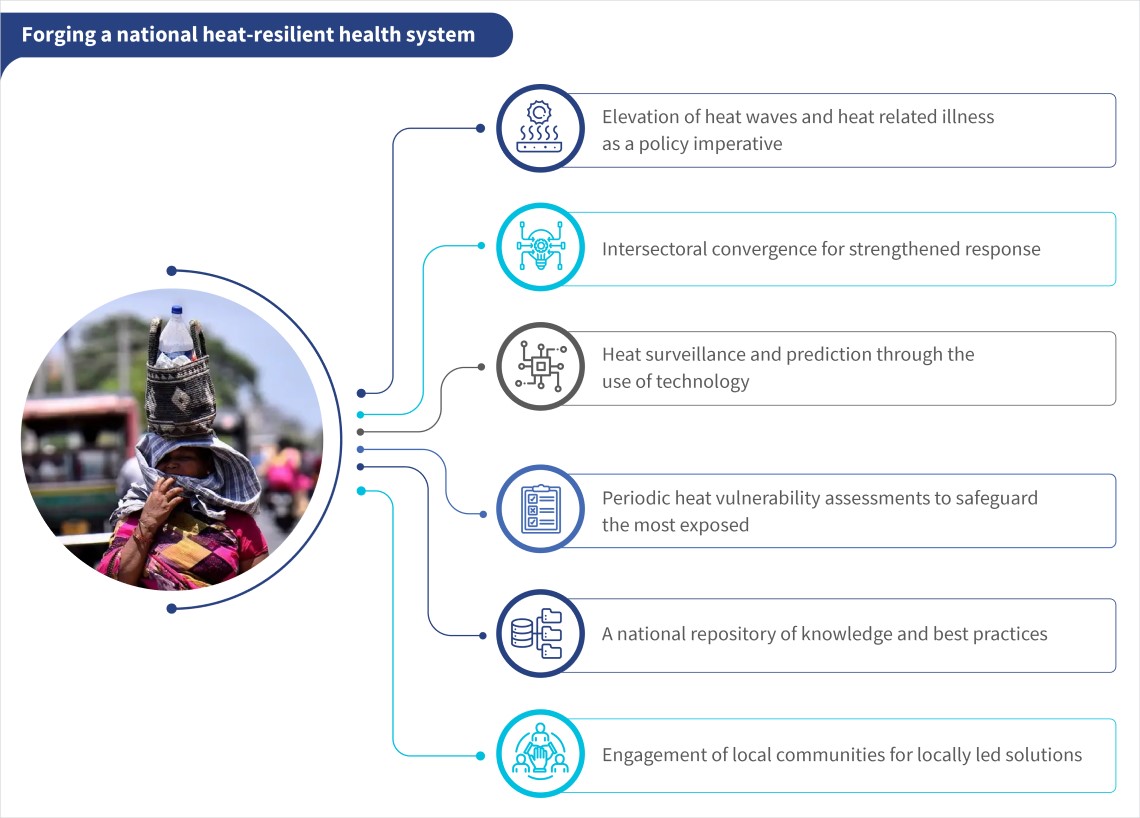

A heat-resilient health system is paramount to improve overall preparedness and response to heat-related challenges. We have identified six instrumental changes needed to adapt to and mitigate heat-related illnesses in urban India effectively.

- Elevation of heat waves and heat-related illnesses as a policy imperative

A fundamental shift in the perception of heat waves and heat-related illnesses is needed at the policy level. The recognition of heat waves as disasters under the Disaster Management Act will unlock critical resources and powers that facilitate a more robust and coordinated response. This reclassification is not just administrative but a declaration of intent to safeguard public health.

- Intersectoral convergence for strengthened response

The fight against urban heat is not one that the health sector can—or should—wage alone. An integrated approach that brings together ministries of health, urban development, energy, and disaster management is crucial. This convergence can occur through inter-ministerial monitoring, such as oversight committees and intersectoral task forces. The country can then streamline efforts, avoid duplication, and ensure a holistic response that addresses the root causes and consequences of heat stress.

- Heat surveillance and prediction through the use of technology

As per the Global Commission on Adaptation, a warning before 24 hours of an impending hazardous event can cut the resulting damage by 30%, and an investment of USD 800 million on such early warning systems in developing countries can prevent losses of USD 3 to 16 billion per year. In the age of digital innovation, technologies offer unprecedented opportunities to monitor, predict, and respond to heat waves. Remote sensing, GIS, and AI-driven forecasting models can provide real-time data crucial for early warning systems. IoT sensors and mobile applications can revolutionize how individuals receive alerts, access information on cooling centers and heat wave safety measures, and lead to real-time patient tracing.

- Periodic heat vulnerability assessments to safeguard the most exposed

Per our study, we must refine our approach to understand heat risks to shield our cities’ most vulnerable population and tailor our systems to be gender-responsive. We can target our efforts more effectively if we institute biennial, in-depth evaluations that focus on the most perilous urban areas and communities.

Identifying hotspots and those at risk isn’t just about mapping temperatures—it’s about mapping needs. Despite existing climate assessments, zeroing in on the specific health threats can guide us to pinpoint and bolster our defenses where they are most needed. This ensures no one is left sweltering in the shadows.

- A national repository of knowledge and best practices

A national repository of heat action plans, research findings, and successful interventions can serve as a valuable resource for policymakers, researchers, and practitioners. This repository can help share strategies and improve the efficacy and reach of heat mitigation efforts. Knowledge is power, and it can be life-saving to manage heat waves.

- Engagement of local communities for locally led solutions

At the heart of any successful public health initiative is the community it serves. We can engage local populations, use the influence of resident opinion leaders, and foster grassroots movements to drive change more effectively than top-down mandates. Community-driven solutions, tailored to each locale’s unique needs and vulnerabilities, can enhance adaptation, preparedness, and resilience. See the whitepaper—“Enabling and financing locally-led adaptation”—to understand ways to engage local communities.

The way forward: A unified response to a shared challenge

The surge of severe heat waves across India’s metropolises is a glaring signal of the intertwined nature of global climate issues. A resilient urban future worldwide warrants a truly coordinated global response and seamlessly integrated local-level strategies for an enduring climate resilience framework.

We also need strategic investments in research to drive product and process innovation to bolster health systems. Such critical advancements must be championed through financial support mechanisms, underpinned by government commitment, and galvanizing the private sector to drive market-responsive solutions.

Crucially, discussions on heat waves should be a sustained fixture on the political stage to spur unwavering political will and facilitate rapid action. Sporadic reactions to heat episodes are a short-sighted fix. A robust, season-spanning strategy is needed to address and adapt to the escalating heat challenges fully.

Living on the edge: The impact of extreme temperatures on Delhi’s informal communities

Multiple cities in India’s northern and eastern regions experienced maximum temperatures that exceeded 44°C this year. The National Capital Region of India is currently reeling from heatwave conditions where temperatures have crossed 45C. Extreme heat disproportionately impacts vulnerable people’s lives and livelihoods particularly those who live in informal settlements in urban areas of the developing world.

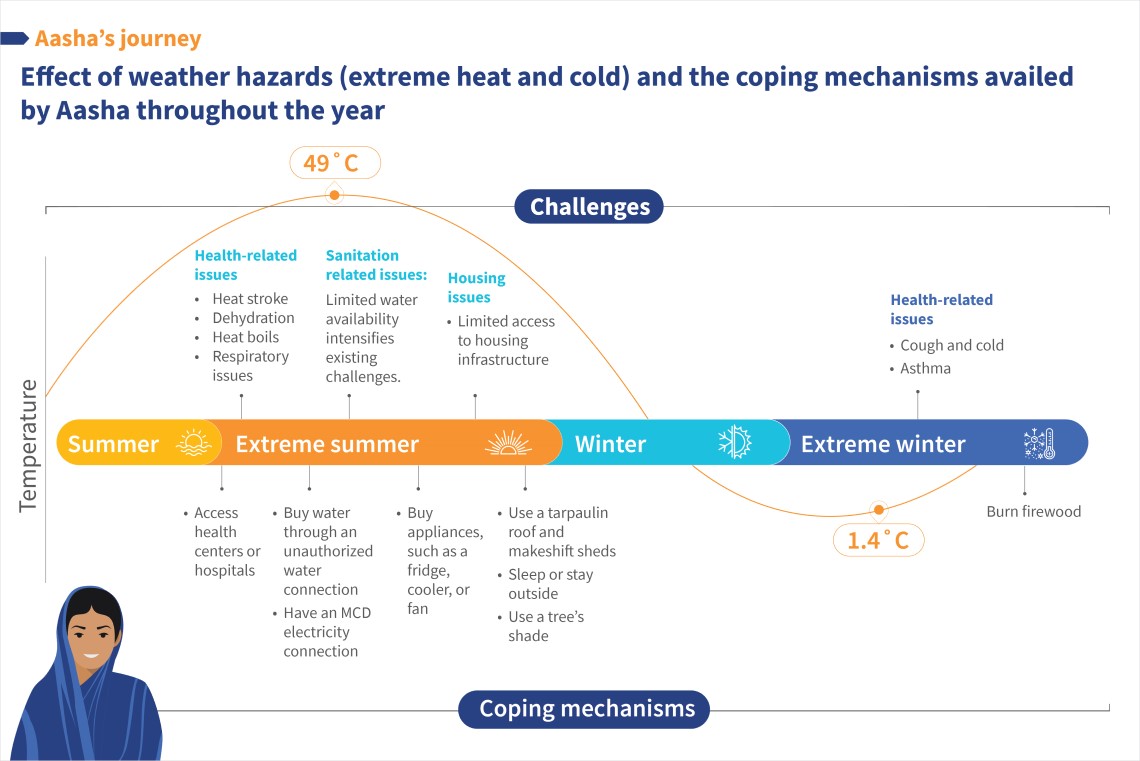

18-year-old Aasha is part of the informal Gadia Lohar settlement situated by the main road in Chirag Delhi, a densely-populated urban village in South Delhi. Aasha says the relentless heat has made her life unbearable and intensified existing health issues for the past few summers. It has made simple tasks, such as finding potable water and other purposes, a daily ordeal.

Aasha and her community have to buy costly bottled water or fetch it from distant sources due to the lack of a formal water supply. Despite her efforts to address the water crisis through complaints to the Delhi Jal Board (Delhi’s water supply department) responsible for the production and distribution of drinking water, little was done. Sanitation is also a critical challenge. Her community has limited access to clean toilets and water, which impacts women’s health in particular. They source electricity illegally from nearby poles but cannot use it to run fans or coolers since it is unstable. Their makeshift “kutcha” houses, with tarpaulin roofs and tin walls, trap heat during the scorching summers. This makes indoor temperatures unbearable and forces the family to sleep outside despite safety risks.

Aasha’s story is not unique and mirrors the struggles of countless other informal settlement residents across the National Capital Region (NCR). The absence of basic facilities and extreme weather hazards make daily life a relentless battle.

Studies indicate that Delhi has been experiencing “dangerous” heat index levels. The latest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report, 2023, highlighted that climate change adversely impacts human health, livelihoods, and key infrastructures in urban areas, particularly for economically and socially marginalized informal urban residents. These groups remain at a greater risk of dehydration, heat cramps, and heat exhaustion, especially during heat waves, which can lead to more severe conditions if not treated promptly.

In its white paper, “Enabling and financing locally-led adaptation,” MSC emphasizes why it is important for policymakers and stakeholders to adopt a holistic systems approach to address the impact of extreme heat on vulnerable communities. Large-scale climate events affect individuals and critical components of the broader system, such as communities, hospitals, and infrastructure. Understanding the drivers of resilience at the individual, community, state, and national levels, can enable us to identify effective interventions that cater to the needs of vulnerable populations.

MSC conducted a study on the impact of extreme temperatures on Delhi’s informal settlements to uncover their experiences in dealing with the impacts of extreme heat. Our study’s findings underscore the impact of extreme temperatures on marginalized communities and highlight their existing struggles with poverty and living conditions. Heat waves exacerbate physical, health, economic, and social challenges due to congested and poor living conditions and their informality.

*MSC’s study, using our flagship MI4ID training approach, collected data from respondents in focus group discussions across seven informal settlements in the NCR.

We uncovered the residents’ limited coping strategies in the face of extreme heat. Short-term strategies people adopted were to cover roofs with wet quilts, seek shade under flyovers and trees, stay hydrated, and take frequent breaks, particularly for physically demanding outdoor jobs. Residents cooked multiple times to prevent food spoilage, often during the early hours of the day.

However, their informality was a constant source of vulnerability. When residents use tarpaulins for shade outside their houses during extreme heat, municipal authorities accuse them of encroachment. The informal residents we spoke to also struggled to invest in solutions, such as pucca houses and electrical appliances, among others, to address the longer and medium-term impacts of climate change on their lives and livelihoods.

Their urgent and immediate focus was to meet basic needs, like food, water, and shelter. They struggle to survive against the elements due to various problems that range from water scarcity and inadequate sanitation to subpar housing and health risks. The impacts of climate change, compounded by poverty and urban inequality, exacerbate their vulnerabilities and affect their health, economic stability, and overall well-being.

The impacts of extreme heat on informal urban residents require dedicated interventions to provide sustainable cooling solutions and support to address the immediate health and economic impacts of extreme heat. Some potential sustainable cooling solutions that could work for such communities include the following:

- Solar-reflective paint on exteriors can lower indoor temperatures significantly;

- Geothermal air conditioning taps into the earth’s stable temperatures for cooling;

- Cool roofs can be constructed with materials that reflect sunlight to help reduce heat absorption;

- Urban green spaces provide natural cooling through shade and moisture release;

- The incorporation of natural ventilation and passive cooling in built environments can help reduce internal temperatures.

These methods offer sustainable ways to mitigate global warming’s impact and enhance vulnerable informal urban residents’ resilience. However, we must meet informal residents’ pressing needs and continued sources of vulnerabilities, such as access to clean drinking water, improved sanitation facilities, and secure housing to build their resilience to extreme heat.

Municipal authorities and policymakers must recognize that resilience to climate change and improvements in overall well-being are two sides of the same coin. They must prioritize interventions that enhance and support slum communities to build resilience to extreme heat. If they understand local knowledge, risks, and practices, they can inform effective policies and interventions tailored to the needs of informal urban settlements’ residents. We require a significant change in access to public services that addresses the vulnerabilities due to informality. We must also find sustainable cooling solutions to ensure that vulnerable informal urban residents become more resilient to the impacts of extreme heat.

The Housing and Land Rights Network (HLRN), located in New Delhi, is a leading organization dedicated to research, education, and advocacy on housing and land rights. MSC acknowledges HLRN’s support in connecting with important informal settlements and community stakeholders across Delhi for the study.

Women’s informal employment in the digital economy: The Future of Work research

A significant gender disparity persists in Indonesia’s labor market. The country’s informal sector employs 64% of women. The diverse sector encompasses own-account workers, casual laborers, microenterprises, and street vendors. Yet the rapid digitization of informal work in Indonesia and its impact on women’s employment remain inadequately understood.

MSC conducted a comprehensive study in collaboration with the Ministry of Women Empowerment and Child Protection of Indonesia to address this gap. It sought to assess female informal workers’ accessibility and experiences in the evolving digital economy. The research was designed to capture these women’s multifaceted experiences and explore how digital trends transform their work in five key areas:

- Women’s day-to-day realities and challenges in informal work and their experiences in informal employment;

- Female informal workers’ access to digital financial services and their usage ;

- The impact of societal norms and caregiving duties on women’s work;

- Opportunities for business growth and skill enhancement available for women;

- The availability and effectiveness of social protection measures and childcare services for informal workers.

The report is based on a survey of 400 female workers across nine Indonesian provinces. It presents actionable recommendations for government ministries, civil society organizations, and public and private sector entities.

The report analyzes barriers women face throughout their employment lifecycle. Female informal workers can fully engage in the job market and benefit from it if they overcome these barriers. This would foster a more equitable labor market and, in turn, enhance female labor force participation rates in Indonesia.

Here are the links to the reports:

1) Click here to download the full report in English.

2) Click here to download the report’s summary in Bahasa Indonesia.