In developing countries, such as India, Kenya, Bangladesh, and Indonesia, cash-in and cash-out (CICO) agents encounter sustainability challenges. These challenges arise from stiff competition, reduced commissions, and low margins from user-initiated digital financial service (DFS) transactions. MSC recommends several solutions to foster agent sustainability. These include evaluation of agent willingness, mobility, technical and soft skills, digital savviness, financial sustainability, ability to identify potential customers, and ecosystem support during the selection of use cases. The implementation of these use cases will help providers drive the financial sustainability of agents and, consequently, promote financial inclusion among low- and middle-income customers.

Blog

Smallholder farmers worldwide are on a perilous journey amid climate change—where are they headed?

“I have never seen such heatwaves in April in Mastung, nor such massive floods in my lifetime. It rained continuously for more than 120 hours in some areas. This much water seems unreal. It has washed away all we had.” (Baloch & Taylor, 2022)

I. Introduction

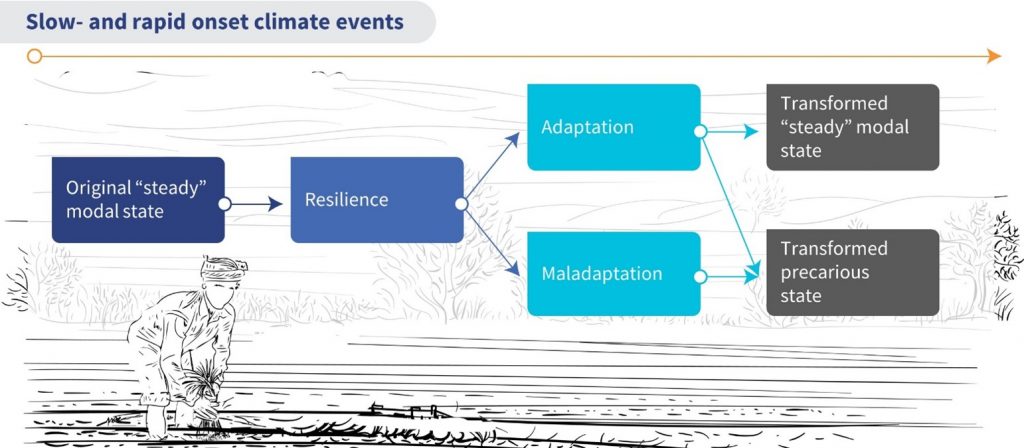

The literature on climate change typically differentiates between slow- and rapid-onset climate events. But climate change events have become progressively more regular and extreme, so the distinction is increasingly irrelevant. Smallholder farmers worldwide bear the brunt of these changes, often facing drought and excess rainfall within a single season. MSC’s work on climate change’s impact on agriculture in Bangladesh, India, and across Africa highlights how farmers’ incomes and assets are being eroded.

If we expect to contribute meaningfully to mitigate this global trend, we must understand the challenges facing smallholder farmers. We must explore the pressures smallholder farmers struggle with and their perilous journeys to build resilience, adapt, and transform their livelihoods.

II. Original “steady” modal state

“We have experienced drought before, but now it is happening almost every year. In the past, we at least had some grain stored from better yield years and got by with it. But these past few years, the yield has been consistently poor. I do not know how we are going to survive the coming winter.” (Onta & Resurreccion, 2011).

Smallholder farmers have nurtured land, crops, and livestock for millennia to earn a living. Those who have small parcels of land and who can invest in agricultural production could make ends meet. These farmers managed the somewhat unpredictable and interlinked cycles with indigenous knowledge and experience. They could usually tide over seasons when pests or diseases attacked, or the weather was unkind. They provide a third of the world’s food. Yet 40% of these farmers continue to live on less than USD 2 a day.

However, as climate change distorts and amplifies weather patterns, smallholder farmers’ ability to manage is increasingly under threat as the deviations from the mode increase. In response, farmers have to build resilience, adapt or transform. Their journey is underway.

For this blog, we adapt LSE’s 2022 definition of resilience. LSE defines resilience as the capacity to prepare for, respond to, and recover from stresses, shocks, and lifecycle events, including hazardous climatic impacts, while minimizing damage to household consumption, societal well-being, the economy, and the environment. IPCC, 2019

However, in 2014 the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) defined “incremental adaptation” as “actions where the central aim is to maintain the essence and integrity of the existing technological, institutional, governance, and value systems, such as through adjustments to cropping systems via new varieties, changing planting times, or using more efficient irrigation”. They contrasted this with “transformative adaptation”, an approach that “seeks to change the fundamental attributes of systems in response to actual or expected climate change and its effects, often at a scale and ambition greater than incremental activities”. So we might see IPCC’s incremental adaptation as resilience.

esilience tends to be more reactive, while adaptation is more proactive and anticipatory, as it involves planning and preparing for future climate impacts. That said, drawing a clear distinction between resilience and adaptation—and, indeed, development—is difficult. Many approaches to enhancing resilience can be and often are implemented as adaptation measures, as we will see in the discussion below. And as McGray et al. of the World Resources Institute noted in 2007, “Rarely do adaptation efforts entail activities not found in the development “toolbox.””

“Adaptation is sometimes seen as being part of resilience. Resilience capacity is described as a combination of: (i) shock absorbing and coping; (ii) evolving and adapting; and (iii) transforming. By this definition, coping is the first and ideal strategy for managing risk. However, when societies exceed their ability to cope, they should be able to adapt to the adverse changes they face” – LSE, 2022.

III. Resilience

Technologies to help farmers enhance their resilience are widely available. These include flood- and drought-resistant seeds, water, and soil conservation techniques, agro-forestry, community-based collaboration, climate information services, and several financial services, including weather-based insurance. In many countries already impacted by climate change, a growing number of farmers are using these approaches to begin to adapt and build resilience.

IV. Adaptation

“Estimated adaptation costs in developing countries could reach $300 billion every year by 2030. Right now, only 21 per cent of climate finance provided by wealthier countries to assist developing nations goes towards adaptation and resilience, about $16.8 billion a year.” – United Nations (accessed April 2023)

Adaptation involves smallholder farmers making significant adjustments to their farming practices and livelihood strategies. Many are similar to, and/or are extensions of the resilience strategies described above. Others require more extensive changes, such as building shelters for livestock to protect them from the sun and excess heat, raising housing and seedling or vegetable beds above flood water levels, or changing from rice to shrimp production in the face of the salination of soil. These require substantially more capital investment than most measures to enhance resilience, and few financial service providers are willing to offer the loan sizes and tenors needed for adaptation. Other examples of adaptation include diversifying income sources to include non-farm activities and the temporary or permanent migration of family members.

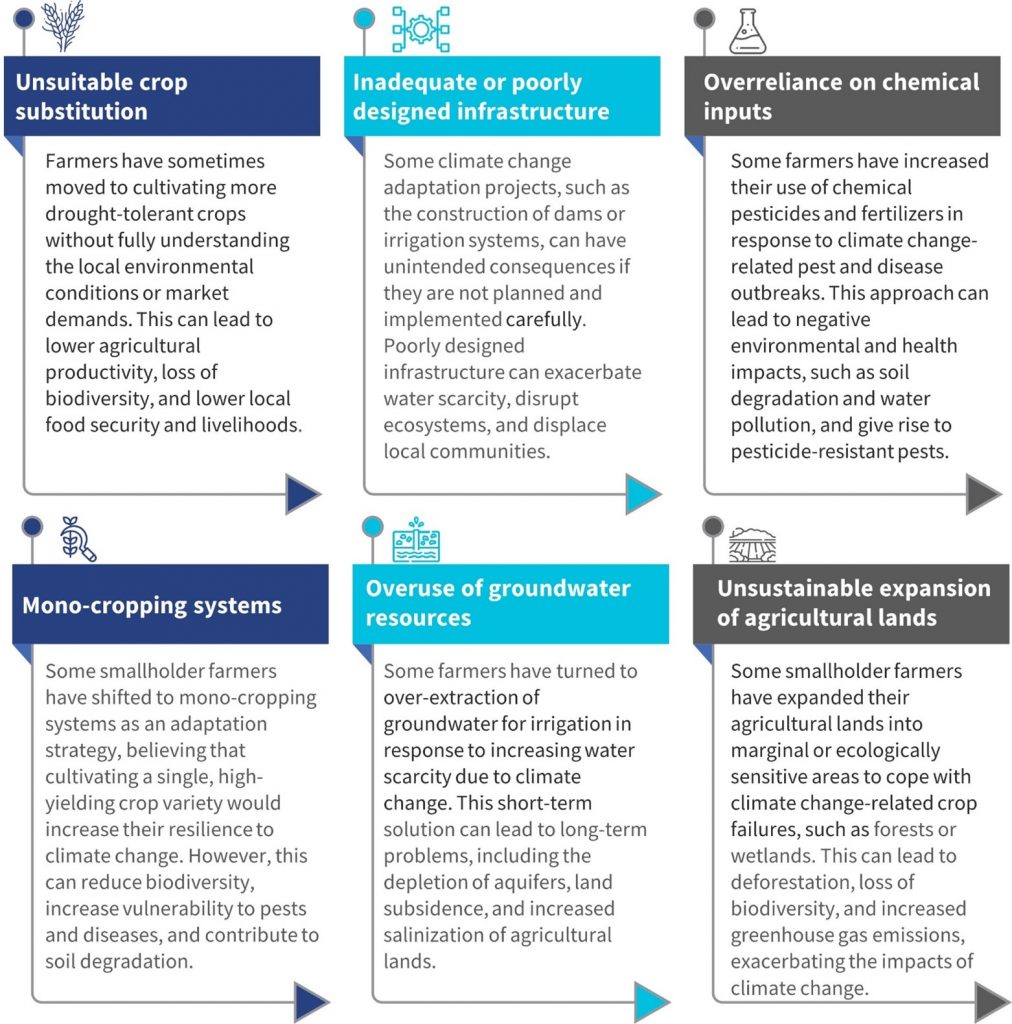

However, as farmers make these substantial changes, they also risk maladaptation. They often end up prioritizing short-term gains and quick-fix solutions. Such misplaced priorities can lead to increased vulnerability and reduced adaptive capacity in the face of evolving climate risks.

V. Maladaptation

“Most of our youth and able-bodied men migrate to the south to look for employment opportunities. Many do not return at the start of the farming season, which affects the availability of farm labor. In turn, the unavailability of labor affects farm operations and crop yield, which has implications for food security in this community.” (Antwi-Agyei et al., 2022).

Maladaptation implies actions or strategies that may inadvertently increase vulnerability to climate change or undermine a farming system’s long-term sustainability. MSC has seen common examples in its work, which include the overuse of fertilizers and pesticides in response to declining soil health or climate change-induced crop diseases. The diagram below outlines other common maladaptation practices.

VI. Positive “steady” modal state transformation

In an ideal world, adaptation should lead to a sustainable steady, modal-state transformation. Such transformation would provide smallholder farmers with long-term climate resilience, enable them to manage the vagaries of the weather, earn an improved and reliable income, and thus secure the family’s livelihood and future. As co-convener of the CIFAR Alliance’s Climate Resilient Agriculture (CRAg) working group, MSC works with various players to identify and enhance digital technology’s role to transform agri-food systems across Africa and Asia. Yet for many farmers, this positive transformation is elusive—not least of all because the vagaries of the weather are increasingly extreme, and the “panarchy” cycles are becoming more unpredictable and unruly.

VII. Negative precarious state transformation

“We are here for three generations. How can we migrate, leaving our land, property, and generations-long memories?” (Ahmed et al., 2021)

The alternative, less positive outcome is where the smallholder farmer and their family are forced to abandon farming altogether, typically after a remorseless downward slope of income and asset depletion. They then often migrate to live in squalor in urban slums as a last resort (Kugelmann, 2020 and Chung, 2022).

VIII. Conclusion

A growing proportion of smallholder farmers are under immense pressure from climate change and being forced on a perilous journey as they try to build resilience, adapt or transform to manage climate events. This journey is not linear but fraught with challenges. However, we have the technologies to positively transform the agri-food systems within which smallholder farmers play such an important role. The challenge is how we can encourage and support farmers to adopt and use these technologies along their journey.

Chhotastock: Democratizing investments for all

Chhotastock is a FinTech startup from Bengaluru in India that works to transform how individuals access and manage finance and investments. It seeks to democratize investments and make them accessible to everyone.

This blog looks at Chhotastock, part of the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program, which is supported by some of the largest philanthropic organizations across the world—Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. Foundation, Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, MetLife Foundation, and Omidyar Network.

The stock market, measured by the Sensex in India, has grown by 12% annually over the past 10 years. This growth has drawn millions of new market investors market who seek better financial returns. Supply-side ecosystem players should continuously innovate and strengthen their offerings to accommodate the diverse needs of young new-age investors. Let us see how Chhotastock does its bit to add value to the ecosystem.

Investors in India’s smaller towns have historically struggled to invest in capital markets. Take the example of Anthony, a recent college graduate with an information technology (IT) degree from Patna in Bihar state. He is tech-savvy but lacks the financial acumen to decide which financial instrument will provide solid returns, considering his time horizon and available funds. His income is limited as he has started his career in an entry-level position. He wants to save a fixed monthly amount for higher studies and has been exploring interest-bearing investments for his limited surplus income.

Millions of people like Anthony need more knowledge and market exposure to start their investment journey. These people struggle with choice and information overload as they deal with the complexity of a wide range of investment offerings.

Why Chhotastock?

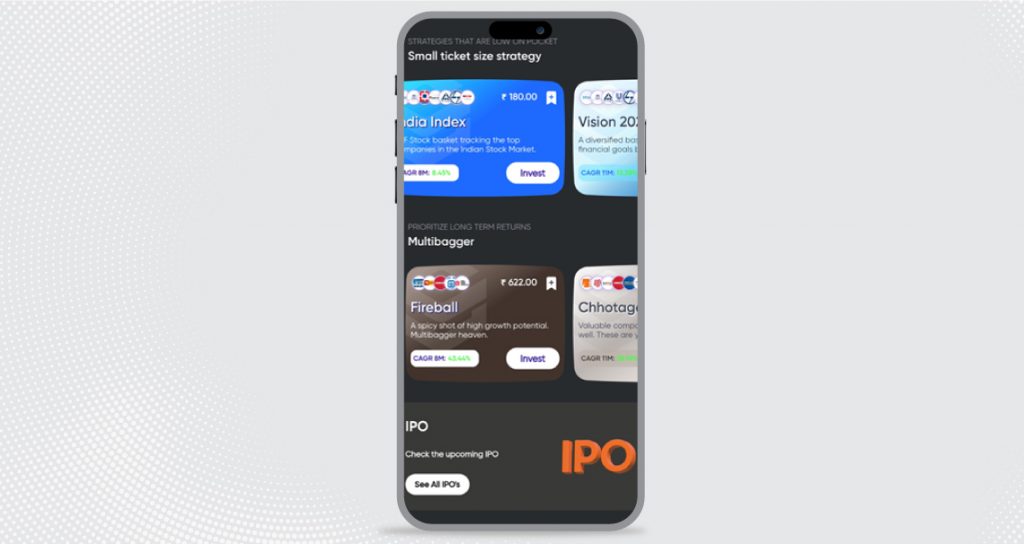

The Chhotastock platform offers to take young, non-professional investors in tier 2 and 3 Indian cities on a simple, reliable investment journey. The app provides market-linked investment opportunities in equity, debt, and peer-to-peer (P2P) lending. The offerings cater to the needs of Gen Y and Gen Z customers who seek active investment strategies with higher returns than traditional options, such as bank deposits. The platform hopes to build trust through a transparent onboarding process and allow customers to transact without hidden charges. It does not access unnecessary cross-application data points, including messages and emails.

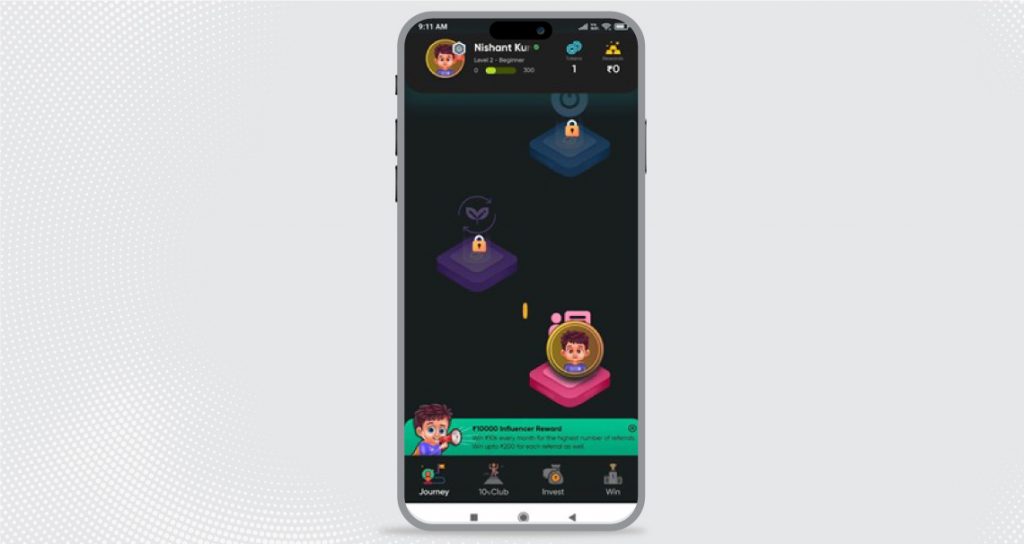

Chhotastock intends to create wealth for the country’s 290 million underserved small investors and make investing accessible, fun, and engaging. The company launched a revised app in February 2023 to achieve this goal. The updated app gamifies the investment experience, which results in an engaging tool for young individuals with small surplus income for mid- to long-term investment opportunities. Chhotastock’s primary offering includes small-ticket debt and equity baskets in which investors can invest as little as INR 100 (USD 1.2) based on specific themes or goals.

The platform primarily has three sources of income: account opening fees, subscriptions, and commissions—for a scaled-up version of the product with unlisted equity buckets, IPOs, and mutual funds order management system. It also plans to introduce additional features to offer users the most popular or high-yielding strategy options. Additionally, Chhotastock earns SDK (software development kit) fees and affiliate commissions from brand associations.

An investment app for Indian youngsters

Chhotastock’s target market stands on the following three tenets.

(a.) An increasing number of new investors joining the stock market are in the 21-30 age bracket. Chhotastock wants to tap into this growing target market while easing its concerns and providing users with opportunities to invest in equities and debt with low-risk profiles.

(b.) An increasing number of youngsters have joined the market, but many remain dormant. As per the National Securities Depositories Limited (NSDL) and Central Depositories Services (CDSL), demat accounts in India increased by 145% from 40.9 million in March 2020 to almost looks stuck to 100 million in 2022. Yet around 75%-80% of these accounts remain inactive. The dormancy stems primarily from retail investors’ busy schedules, negative experiences with an agent or broker, and lack of awareness of trustworthy investment platforms.

(c.) Young Indians are hooked on fantasy sports, potentially leading to poor financial health. India has the largest fantasy sports user base worldwide, with 130 million customers and a market size of INR 346 billion (USD 41.73 billion) as of March 2021. Indians love gamified experiences. Chhotastock is betting on its gamified user journey to encourage users to learn about financial markets, grow their investments, and improve their financial health.

Founder’s journey

Like many engineering graduates, Chhotastock’s Founder, Mithun, started his career as an Engineer at Wipro, after which he worked with India’s largest trading platform. Eventually, he launched Blitz, a venture focused on algorithmic trading for index futures. The firm successfully met its targets and generated profits. Following Blitz’s success, Mithun saw an opportunity to address the needs of those eager to invest in India’s booming market yet lacked the awareness to take the plunge.

Chhotastock is Mithun’s attempt to address this gap by using knowledge and tools from earlier ventures to build a platform that makes equity investing accessible, simple, and less time-consuming. Mithun has made peer-to-peer (P2P) investments possible and enabled alternative investment opportunities for platform users. P2P investments are also linked to the functionality of Save Now Buy Later. Customers can invest in the P2P debt market and use the proceeds to purchase aspirational goods, such as mobiles and laptops. Mithun considers this a milestone for Chhotastock since it offers a better alternative to the current buy-now-pay-later (BNPL) offerings that promote using credit for consumption needs.

The journey so far

Chhotastock started as a B2B2C model offering easy plugins for Siply’s customers. After its products succeeded on Siply, it attracted other companies that wanted to diversify investment solutions for their customers. In October 2022, Chhotastock launched a standalone B2C platform.

In the 10 months since Chhotastock’s B2C app launched, it reached the second spot on the Google Play Store in the FinTech category. It also earned a place among the top 500 wealth tech startups that could potentially revolutionize the FinTech ecosystem and democratize the investment space. It has also reached a registered user base of 3.1 million, with more than 40% of users coming through its mobile application.

Chhotastock plans to launch a fleet of enhancements and features to facilitate financially literate and investment-ready youth. The primary target segments include customers from tier 2, tier 3, and smaller cities, primarily first-time investors who are new to the job market, part-time workers, gig workers, and students who have spare money and wish to learn to invest using a gamified approach. With this, Chhotastock hopes to break this segment’s psyche of high dependency on credit and put them on the path to invest and achieve their financial goals.

Chhotastock’s challenges—and its gamified response

Chhotastock lowers the investment hurdle for its customers when they sign up by keeping the initial investment at a low INR 100 (USD 1.22). Yet the platform faces several challenges, including the high churn rates InvestTechs typically encounter, choice overload, and lack of customer discipline to continue investing. Chhotastock plans to gamify the investment experience further. It has introduced in-house games to create the initial hook and ongoing user engagement. Additionally, the app represents the customer’s investment experience through levels and hurdles, giving it a more gamified feel. Its leaderboard prompts competition among users to invest regularly to reach the top rank and receive exciting rewards.

FI Lab support for Chhotastock

The FI Lab’s technical support Chhotastock consisted of capitalizing on its strengths to transform the startup into a preferred investment platform. The Lab helps Chhotastock build a digital marketing strategy to reevaluate its digital journey, positioning, and customer segmentation through different media campaigns. Influencer marketing will seek to bolster Chhotastock among the target audience further, increase the number of registered users, and improve traction—including average spending on the platform.

What next?

Chhotastock has a clear vision to build a trusted investment platform for Bharat and intends to introduce new financial products. One such offering is social trading to help investors follow Chhotastock expert investors and replicate their strategies in their investment portfolios. Thanks to its innovative and customer-centric design approach, Chhotastock is on the path of rapid growth as participation in capital markets intensifies. If it continues apace, Chhotastock is poised to emerge as a vital player that will redefine the investment journey of customers like Anthony and countless others in India.

This blog post is part of a series covering promising FinTechs making a difference in underserved communities. These startups receive support from the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program. The Lab is a part of CIIE.CO’s Bharat Inclusion Initiative, co-powered by MSC. #TechForAll #BuildingForBharat

Rydo: A ride with pride

This blog is about Rydo, a startup in the Financial Inclusion Lab. The Lab is an accelerator program supported by some of the largest philanthropic organizations in the world, including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, J.P. Morgan, Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, MetLife Foundation, and Omidyar Network.

“Rydo has helped me stand up on my feet again,” said Ravi beaming with happiness as he waited for his passengers to sit in his autorickshaw. Ravi used to drive a rented autorickshaw in Bengaluru, but when the pandemic hit, he had to return the vehicle and go back to his village near Tumkur—a district 70 km from the city. Once the pandemic was over, Ravi decided to rent another autorickshaw and drive in Tumkur, but his daily earnings were much less than he had hoped.

Sometime later, Ravi’s friend told him about a new ride-hailing service called Rydo that had launched in Tumkur. Earlier, Ravi had heard about his friends driving for Ola and Uber in Bengaluru and earning a good income. Ravi thought that Rydo seemed similar to Ola and Uber, so he decided to onboard.

Last-mile service providers, such as auto drivers, drive the paratransit space in India. But the current ride-hailing ecosystem offers them limited benefits. Rydo is a ride-hailing app that seeks to provide the best value to drivers by providing them with a better livelihood. It also improved the drivers’ access to financial services, such as credit and insurance.

The lightbulb moment

Rydo is the brainchild of Prakash and Vinay. Their common aspiration to work to uplift the society, brought them together. Prakash is an ex-banker, and Vinay is a Chartered Accountant. Both have more than two decades of experience.

They met at their previous workplace—a technology firm—and decided to build Rydo together. They started Rydo to boost entrepreneurship among low-income individuals by giving them suitable technology and financial support. The founders decided to focus on mobility, especially three-wheelers, due to the large market size, limited innovation in the sector, and ability to create a significant impact, especially in Tier-2 and Tier-3 towns and cities.

How does Rydo differ from the existing ride-hailing services?

Presently, ride-hailing technologies are not active in Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities since the average number of rides and the shorter distances do not suit their economics. Rydo can tap this opportunity to enter these 200+ cities and offer its services.

The founders launched Rydo in Tumkur, Karnataka, based on extensive research and market potential. The founders’ main goal is to mitigate the high wait time between rides, which leads to a loss of earnings for the drivers. They also want to provide affordable credit options to drivers based on their ride data.

As an alternative to the commission-based model of other ride-hailing apps, Rydo offers a subscription model where the platform enables drivers to accept rides and charges a fixed fee daily to remain on the platform. The subscription model helps attract more drivers, especially those who initially resisted onboarding to ride-hailing platforms, as they had to forego a higher percentage of their ride income to these digital platforms.

Other benefits to the drivers

A typical driver associated with Rydo is provided with hospital cash insurance, which gives coverage for any hospitalization for more than 24 hours, making it a lucrative offering. Rydo also encourages drivers to nudge customers to download the Rydo app, for which they get a commission, followed by a commission for every ride the customer takes on the Rydo app.

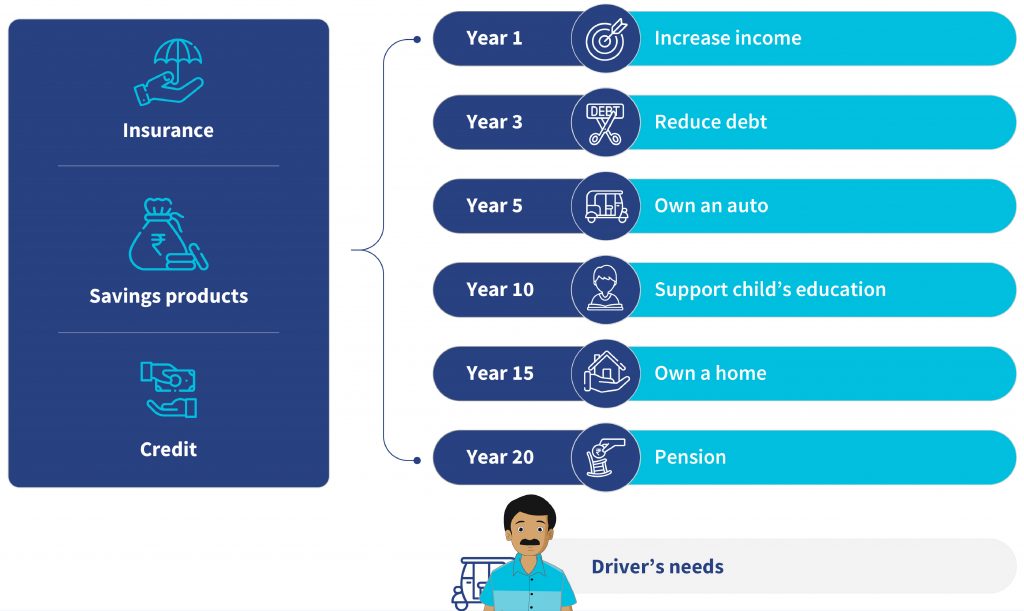

Besides these short-term incentives for drivers, the founders also plan to look at the long-term needs of drivers and create a system to fulfill them over time.

Traction in Tumkur

After its launch in April 2022, Rydo quickly became the go-to app among Tumkur’s driver community. To gain passengers, Rydo relied on organic marketing to limit its initial burn rate and test the product’s market fit. Soon, Rydo could build momentum in Tumkur, and the eight-month-long pilot helped Rydo onboard 225 drivers and 3,200 passengers. Rydo completed 6,000 rides of the 11,500 ride booking requests by passengers, with a success rate of 50%, all at a nominal marketing cost.

Challenges and opportunities for Rydo

While the founders’ vision of challenging the status quo to empower drivers is praiseworthy, several roadblocks persist in the journey. The ride-hailing business is capital-intensive due to the high customer acquisition and retention costs. In addition, the cost of map service to allow passengers to know drivers’ location and vice versa is very high, making the per-ride unit economics more challenging. Another area for continuous improvement is to increase driver stickiness and loyalty on the Rydo platform.

Rydo has a mid- to long-term roadmap to overcome these challenges. These roadmaps include developing organic marketing strategies, using social media influencers, and onboarding Rydo drivers to promote the app and reduce user onboarding costs. Rydo has also partnered with a competitive service provider for the map to reduce the cost of their operations.

Support from the FI Lab

Based on the challenges Rydo faced, MSC identified three areas to support the firm in the mid-term. A key focus area was supporting Rydo with a digital marketing strategy to boost customer downloads and increase its rides per day. The digital marketing activities in Tumkur helped Rydo create a blueprint for further scale-up. The digital marketing activities helped Rydo acquire customers at a lower cost and boosted the number of app downloads by 50%.

Giving credit facilities to drivers can ensure high stickiness to the Rydo platform. MSC helped Rydo partner with suitable NBFCs and FinTechs to provide its drivers with credit facilities using their ride data. Our team also helped Rydo choose the right payment partner to enable automated subscription fee payment and direct loan settlement against customer payments. This model will improve the visibility of the driver’s income through Rydo and encourage more lenders to associate with Rydo drivers and provide them with credit.

What next for Rydo?

Rydo wants to impact the lives of auto drivers across India and enable them to use business support systems through technology. Rydo has planned multiple activities for the future to achieve this, as listed below:

A) Expansion:

1) Geographic: The founders are keen to expand into geographies adjacent to Tumkur. For now, the founders will focus on two or three states in South India in 15 cities where Rydo can make a difference. They have created the blueprint based on their experience in Tumkur. Rydo’s business model can break even at 3,000 rides per day, giving them a unique profitability advantage at the city level. This number forms only 5%-7% of total daily rides in a city like Tumkur.

2) Sectorial: Rydo founders also want to enter other sectors, including two-wheeler logistics, transportation, and delivery, among others, to make it a sizable player in urban last-mile mobility.

3) Product: With the launch of its 2.0 app version, Rydo will also facilitate unsecured and secured lending for the drivers in partnership with a few lender partners. While secured lending will comprise vehicle loans against hypothecation and property loans, it plans to disburse sachet loans for unsecured lending.

B) Gamify the in-app journey: Rydo also plans to gamify the in-app journey, where driver benefits, such as credit and insurance, will automatically unlock as the drivers achieve predefined business milestones, such as the number of rides. These efforts will ensure the driver benefits on the Rydo platform are more sustainable and aligned with its overall business goals.

C) Associate with Beckn protocol or Open Network for Digital Commerce (ONDC) mobility: The Rydo app 2.0 will enable ONDC mobility. It will allow passengers to request rides from any consumer-facing third-party ONDC-enabled app. This strategy is critical to Rydo’s expansion as it allows them to focus on onboarding drivers while using third-party apps to generate ride requests by the passengers, minimizing their customer acquisition cost.

But a few challenges remain on this front as the customer-facing ONDC apps are still in the build stage, mainly focusing on e-commerce followed by the mobility sector. The network effect through ONDC will take some time to gain traction. However, Rydo can take advantage of it.

Rydo showcases how democratizing solutions can boost India’s entrepreneurial journey in Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities. It seeks to be the first to provide fair-priced auto-hailing services across India and help more than 4.5 million auto drivers across most Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities in India to earn a better livelihood along with improved access to financial services.

Money Purse Handbook

The Self-Help Group (SHG) Model in India has been instrumental in improving the financial health of households. It also empowers women to participate actively in household financial decisions. However, most SHG members have limited digital and financial literacy. Therefore, they do not qualify for the parameters defined by the government for SHGs to avail of loans. MSC studied the SHG solution, Money Purse, developed by Anniyam Payment Solutions, to digitize the SHG value chain.

GoGullak- Making personal finance management easier

This blog looks at a startup called GoGullak, part of the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program, which is supported by some of the largest philanthropic organizations across the world—Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, J.P. Morgan, Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, MetLife Foundation, and Omidyar Network.

India is home to ~450 million blue-collar workers, most of whom earn a decent income but struggle to save adequately due to lack of appropriate tools. Piyush is one of them. He works in a factory in Delhi and earns INR 20,000-30,000 (USD 244-365) monthly, depending on the incentives he receives. He often struggles to manage his finances and resorts to personal loans for exigencies. Once he pays off his EMI and other necessary expenses, such as school fees and rent, he struggles to manage his remaining expenses.

Piyush knows that budgeting and tracking his expenses would help, but he finds it challenging to follow through every month. He tried a few ledger-keeping applications, but these did not suit his needs as they all worked after expenses had been incurred and did not help in decision-making when making payments. He continued to struggle to pay monthly EMI or save and invest to build an emergency fund.

Millions like Piyush face fail to manage their finances due to a lack of knowledge about financial planning and limited access to appropriate tools through which they can plan. This struck a chord with former engineers Avinash, Yashraj, and Yash —the co-founders of GoGullak.

Since their college days, the trio has been passionate about building a scalable product that could create real social impact. Initially, they worked on a financial education solution for investing in stock markets but quickly realized that financial management is a bigger cause of concern among India’s middle-income investors. Most users used several ledger-keeping apps to manage their finances but struggled to save enough money for investments. This led them to conceptualize GoGullak in February 2022, christening their venture based on the Hindi word for traditional earthenware coin boxes children use to save small change: “gullak.”

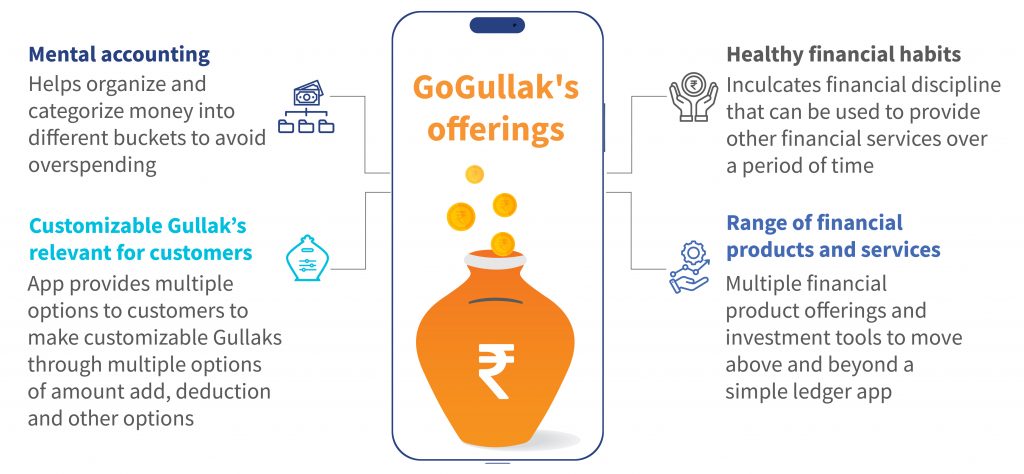

The GoGullak pitch: Building better financial habits through the concept of mental accounting

GoGullak is an aspiring neo-banking platform that helps users align their financial goals through real-time budgeting like an orchestrated finance platform that makes financial management as easy as arranging files on a computer. GoGullak uses the principles of mental accounting, popularized by behavioral scientist and Nobel laureate Richard Thaler as a way people organize and categorize money as per its intended purpose. This helps users better understand their spending habits and make more informed financial decisions. Users can park their money for specific purposes in separate micro-containers in their accounts, just like physical Gullaks.

A major problem that users like Piyush face is the inability to control their spending when all of their money looks the same in a single digital account, even though each rupee may have a different purpose.

To solve this problem, GoGullak allows users to save money for different categories, such as rent, bike expenses, subscriptions, food, and EMIs on the app. Unlike a typical savings account in a bank, GoGullak helps users to create labeled micro-containers, with each gullak acting as a sub-account on top of a single bank account. This allows users to budget their monthly expenses for each category on the app. The users pay through the gullaks created for each category on the app instead of conducting a post-facto analysis of the expenses incurred in the month. Users can club similar spending categories or earnings and manage them individually through these gullaks.

GoGullak offers complete customization of each gullak to each individual’s needs and offers them the flexibility to budget, track, and pay conveniently through a single platform.

An ecosystem approach to build the business model

The founders understood that if they could create value for users when they sought to plan, store their money, and pay through GoGullak, they could uncover an opportunity to monetize the platform. They could provide users with suitable products, such as mutual funds, insurance, white and electronic goods with save now, buy later (SNBL- where customers can save in installments to buy products in future) while offering them good consumer brand deals. In the process, the founders want to create an ecosystem where consumer brands and financial institutions can use transaction data to offer GoGullak customers tailored offerings.

GoGullak’s ecosystem will help users plan, save, invest, and purchase transparently while promoting good financial behavior. “I am focused on building long-term sustainability for the user and GoGullak. Anything bad for users in the short term, even if it is good for GoGullak’s revenue, is not sustainable. GoGullak’s analytics will nudge users to adopt sustainable financial practices and spending through the platform for the long-term,” notes Yash, GoGullak’s co-founder.

GoGullak’s vision is to ensure that users enjoy financial freedom and bring financial discipline back into their lives. This vision resonated with leading financial institutions in the country and has encouraged them to tie up with GoGullak to offer its solution to their customers. GoGullak is currently a part of the Fincluvation program with the India Post Payments Bank (IPPB). Under this IPPB willl leverage GoGullak’s solution for its customers.

Challenges for GoGullak

Automated personal finance management lies at the core of GoGullak’s value proposition. While this is valuable and holds appeal across different customer segments, GoGullak’s product roadmap and promotion will have to ensure that the initial hook of financial management translates into adopting other products like investment, insurance, financial analytics, and SNBL, as these are key revenue sources. In this process, another challenge for GoGullak is to make an intuitive user interface so that users can navigate through various products and features with the least possible friction. Besides these, system integration with banks and other financial institutions to provide a smoother user experience has been a constant challenge for the team.

Support from FI Lab

Under the FI Lab program, MSC helped GoGullak identify its target segments, understand their behavior, and help the founders identify gaps in the app’s UI/UX journey. The research with salaried classes and micro-entrepreneurs revealed pain points in managing their personal finances. It helped identify the key focus areas for GoGullak to build loyalty and retention. The insights helped the startup refocus and target its efforts towards a particular range of income and occupation segments. GoGullak’s proposition resonated the most with these segments and helps them address their pain points efficiently.

The MSC team also helped GoGullak build a B2C and B2B2C GTM strategy and created an implementation roadmap post its launch.

Building financial discipline and a digital future

GoGullak plans to boost its customer reach and performance. As it grows, it will focus on big data and artificial intelligence to build services that will make personal finance management easier for its users. With the vision to make GoGullak universally accessible and helpful, it expects to create an impact on the low- and middle-income segments. In addition, the team is working on creating a voice-based chatbot in the native languages of India to improve the usability of its app for even low-tech savvy persons. “Ultimately, we want to give everyone their financial assistant, which will act as their second brain for personal finance,” says Avinash, the co-founder of GoGullak.

The co-founders believe that by making financial planning and management more accessible and useful to everyone, they can empower people to take control of their financial future and achieve their financial goals.

This blog post is part of a series that covers promising FinTechs that have been making a difference in underserved communities. These startups receive support from the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program. The Lab is a part of CIIE.CO’s Bharat Inclusion Initiative and is co-powered by MSC. #TechForAll, #BuildingForBharat