“… investments in adaptation and resilience-building around the world continue to fall far short of documented needs. It is also increasingly clear that although public finance for adaptation has increased, it will not suffice. Private sector investment is critical to closing the adaptation finance gap.” – The World Bank Group and the Global Facility for Disaster Reduction and Recovery (GFDRR) (2021).

The adaptation finance crisis

While countries worldwide have pledged to prioritize climate adaptation, the gaps between promises, delivery, and needs are alarming. Back in 2009, at the COP15 in Copenhagen, developed nations promised to set aside USD 100 billion each year by 2020 to help developing countries mitigate and adapt to climate change’s impact. At the COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, these promises were further escalated to USD 300 billion each year by 2035—but this depended on the involvement of private sector capital.

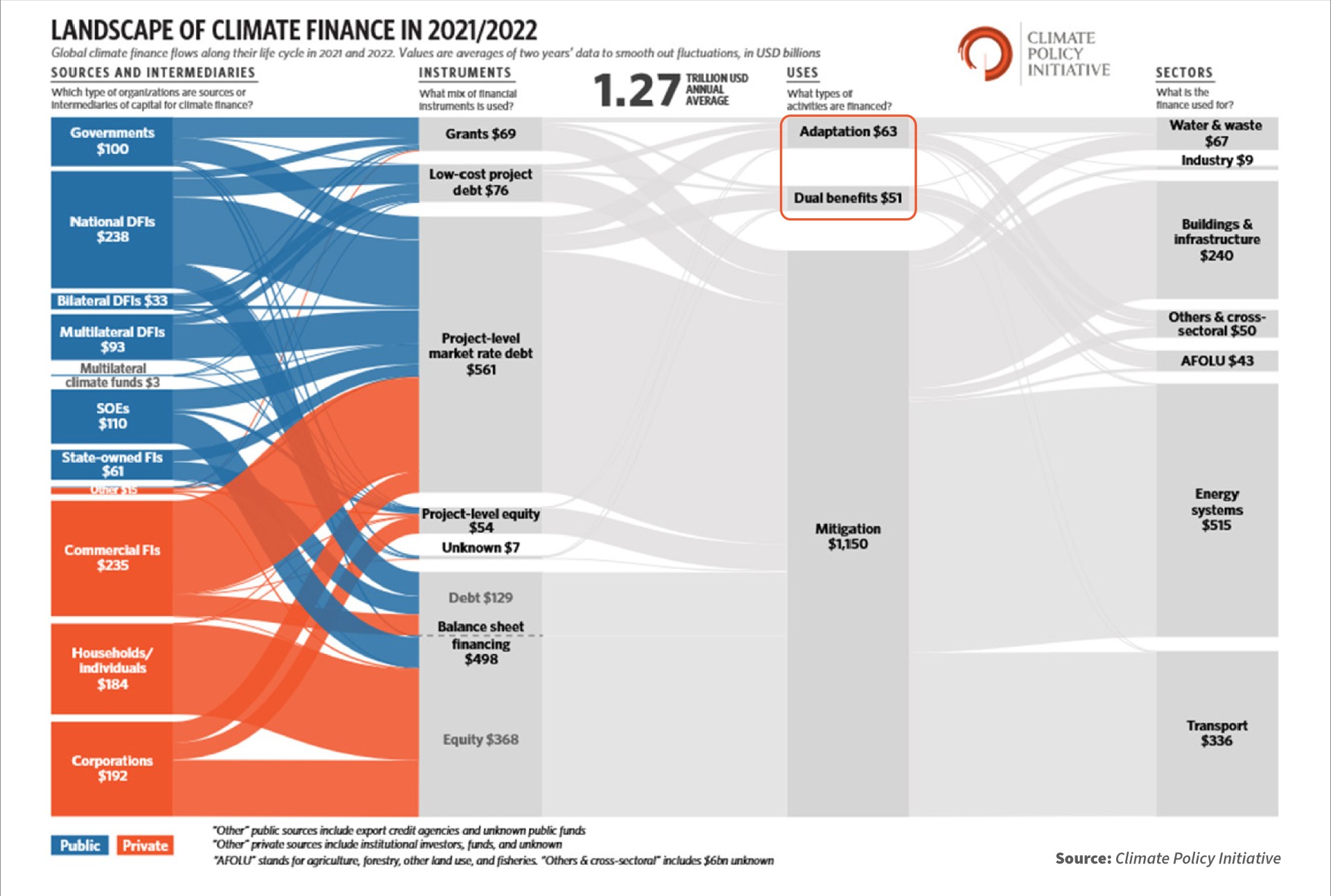

Yet, developed countries only contributed about USD 83.3 billion in 2023 toward climate finance for developing nations. Meanwhile, only USD 29–35 billion each year actually reached developing countries in 2022, with a meager 10–15% trickling down to local communities due to bureaucratic inefficiencies. Today, developing countries require USD 215–387 billion each year to adapt to escalating climate impacts—a figure that the Climate Policy Initiative estimates will balloon to USD 315–565 billion annually. Additionally, while public finance for climate adaptation has increased, private sector contributions remain extremely low—only about 3–5% of total adaptation finance.

The gap is not just financial but existential. If we are to close the gap, developed countries must honor and expand their commitments. They must use blended finance to crowd global and local private-sector funding.

Locally-led adaptation (LLA)

Locally-led adaptation (LLA) shifts agency from international donors and national governments to local communities, which enables them to define, design, and monitor adaptation actions. The approach recognizes that communities in regions, such as Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia—where more than 60% of people rely on smallholder farming or informal enterprises—possess nuanced knowledge of hyper-local risks.

However, most traditional LLA approaches use a comprehensive, one-size-fits-all model, where local governments and communities design adaptation plans collaboratively. Yet, this comprehensive approach can gloss over the diverse financial capacities and structural needs of different actors—local governments, MSMEs, farmers, and vulnerable households.

While the global discourse acknowledges the importance of LLA, actual implementation remains hindered by structural inefficiencies, inadequate funding mechanisms, and top-down decision-making processes that marginalize local voices. As the IIED’s LIFE-AR notes, “The choice of delivery mechanism—local vs. higher-tier—depends on the stakeholder. MSMEs thrive with decentralized finance; infrastructure requires centralized coordination.”

We propose a differentiated model that tailors adaptation strategies to specific segments and enables complementary private-sector finance to support adaptation initiatives. The model draws on existing work under the ADB’s Country Risk and Policy Platform (CRPP) and UNCDF Local Climate Adaptive Living Facility (LOCAL) programs in Gambia, Ghana, and Uganda.

Strengths and gaps in the comprehensive model

The comprehensive LLA model has played a crucial role to shift adaptation decision-making to the local level through pioneering frameworks, such as the UNCDF’s LoCAL and IIED’s LIFE-AR initiative. These frameworks emphasize inclusivity and decentralized governance to ensure community voices shape adaptation investments.

However, the comprehensive approach typically fails to recognize that local government officials often struggle to identify, still less meaningfully engage with, very poor, climate-vulnerable communities. Furthermore, the extent to which local governments can effectively raise funds and reach the most climate-vulnerable populations varies significantly. Two major factors that underlie this are the capacity of local government officials and the size, structure, and mandate of local governments, many of which are prohibited from raising funds.

A segmented model for LLA

A more effective LLA model could be to recognize the very different types of stakeholders involved, as the IIED has clearly identified. This approach requires us to segment adaptation responses based on three key groups:

1) Local government—driving large-scale infrastructure

Local governments responsible for large-scale adaptation infrastructure, such as flood barriers, irrigation systems, and resilient transport networks, require long-term financing mechanisms alongside public sector oversight to implement these projects. This positions local governments as ideal recipients of institutional funding from sources, such as the Green Climate Fund (GCF) and development banks.

Governments can also tap into capital markets by issuing municipal bonds, an underutilized tool in most developing countries. A successful example of this approach is Cape Town, South Africa. In 2017 the municipality floated a USD 83 million 10-year green municipal bond that was four-times oversubscribed. The bond is funding climate-resilience projects such as water-capture and storage infrastructure, alternative treatment plants, and new flood-defence works. This demonstrates how public financing tools can align with decentralized adaptation planning to ensure sustainable infrastructure development.

Case study: Kenya’s County Green Investment Facility

Based on its work on the County Climate Change Fund (CCCF) Mechanism, FSD Kenya commissioned the county green finance assessment, which provided the first analysis of the green assets and potential at the county level. This work demonstrated the vast potential for projects that can be developed to enhance climate resilience and provide opportunities for green finance. However, county governments require support to package these projects and ensure they manage risks effectively at the global, macroeconomic, national, and local levels.

Collaboration is required to bridge this gap and channel green finance to communities through a pipeline of investable projects that align with investor expectations and address potential concerns. In response, FSD Kenya established the County Green Investment Facility to support 10 county governments to access finance for community-driven green development initiatives.

2) MSMEs and farmers—unlocking financial services for adaptation

Micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) and agriculture employ around 70% of workers in low-income countries. MSMEs are critical economic players in local adaptation but often lack tailored financial products. Through credit, insurance, and other financial services, MSMEs and farmers can invest in climate-smart technologies, such as drought-resistant crops, renewable energy solutions, raised homesteads, and solar water pumps. Credit also enables them to build business continuity strategies to withstand climate shocks and generate local employment opportunities, thus strengthening community resilience.

Despite this, many adaptation finance models do not fully engage the private sector or use it to complement their work. Only 2% of total global climate finance reaches MSMEs. Unlike local governments, inclusive financial service providers (IFSPs) that lend to MSMEs often lack access to large-scale public funding, particularly for climate-vulnerable MSMEs. However, they could mobilize private capital, mainly if supported by blended finance mechanisms, such as partial loan guarantees, credit lines, and climate insurance.

The UNCDF’s LoCAL program pioneered performance-based grants to support community-led initiatives. Yet, it initially overlooked private-sector financing mechanisms that could help MSMEs scale their adaptation efforts. However, new models are emerging to bridge this gap. The UNCDF and SNV’s GrEEn Project in Ghana has demonstrated how blended finance can de-risk private investment in climate-resilient MSMEs. The initiative offered first-loss guarantees and co-financing incentives to mobilize private bank loans for 1,200 MSMEs, with 40% securing follow-on investments.

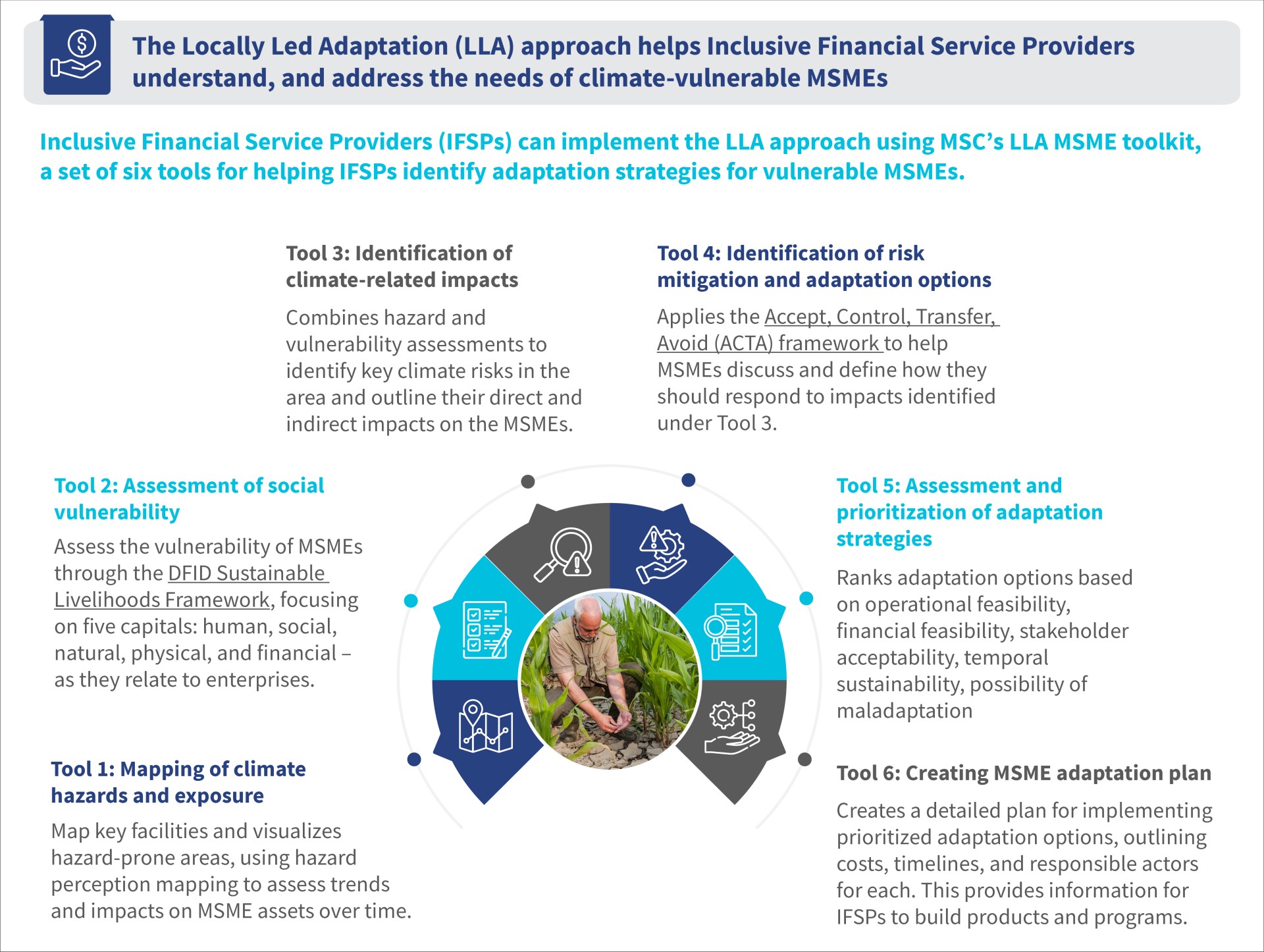

The CGAP and MSC note that IFSPs provide an excellent channel to deliver financial services to climate-vulnerable MSMEs and farmers. However, few IFSPs currently offer products tailored to climate resilience and adaptation. MSC has developed an LLA toolkit focused explicitly on this segment to help IFSPs better understand and respond to the needs of MSMEs.

Case study: BRAC’s climate-smart microloans

These loans are designed to help smallholder farmers and women-led MSMEs in Bangladesh build resilience against climate shocks through accessible financial products. These include floating garden loans, which enable hydroponic farming on water hyacinth rafts in flood-prone areas, crop loans for saline-tolerant seeds, such as the “BINA dhan-11” rice, and livestock insurance-linked loans that provide drought-resistant animals paired with insurance coverage.

These loans have interest rates of 10–15%, which is significantly lower than informal lenders, and flexible repayment schedules aligned with agricultural harvest cycles. The loans typically range from USD 100 to USD 500 and have reached 500,000+ households since 2008. The program has boosted crop yields by 30% for farmers who adopted saline-tolerant varieties and increased incomes for those using floating gardens in flood-prone haor wetlands. BRAC mitigates risks of defaults due to climate disasters by incorporating post-disaster grace periods. It also offers emergency loans and bundles insurance with loans to ensure financial sustainability and empower vulnerable communities to adapt sustainably.

3) Vulnerable community members—accessing social protection mechanisms

The poorest and most climate-exposed populations—subsistence farmers, informal laborers, and disaster-affected communities—often lack access to credit or the ability to repay loans. Instead, they require grant-based support to build resilience to climate impacts and recover from them.

These populations benefit more from loss and damage compensation for climate-related disasters, social security grants to support basic needs and recovery, and community-based adaptation funds that provide small-scale assistance for localized challenges.

Case study: KALIA

The Government of Odisha’s KALIA program (2018) supports climate adaptation indirectly through financial assistance. It provides INR 5,000–10,000 (USD 57-115) per year for agricultural inputs, INR 12,500 (USD 144) for livelihood diversification, risk mitigation tools worth INR 200,000 (USD 2,300) in the form of life and accident insurance, and INR 50,000 (USD 575) in interest-free loans to farmers. This support enables investments in drought-resistant seeds, non-farm livelihoods, such as poultry and fisheries, and adaptive technologies, such as drip irrigation.

These measures enhance resilience against climate shocks, such as cyclones, floods, and droughts. They supplement Odisha’s Climate Change Action Plan (2021–2030) and the central government’s National Innovation on Climate Resilient Agriculture (NICRA). For details, see the KALIA Guidelines.

A multi-tiered approach to local level adaptation: The role of private finance

The ongoing evolution from a comprehensive approach to a segmented LLA model improves efficiency, equity, and scalability in climate finance. This approach tailors interventions to the distinct needs and financial capacities of three key groups—local governments, MSMEs, and vulnerable communities—to unlock more targeted investment opportunities.

Unlike comprehensive approaches, which often struggle to attract large-scale financing, a differentiated model can ensure that private capital, public funds, and grants are directed to the actors best positioned to use them effectively.

This evolution of locally-led adaptation aligns with the Paris Agreement’s core principle of leaving no one behind while harnessing private sector investment to fill the adaptation finance gap.