In collaboration with multiple partners across countries, MSC has collated inspiring stories of grassroots leaders. The booklet shares a snapshot of their journey, experiences, and insights and is a testimony to their grit and resilience. It also gives us a glimpse of the hardships women grapple with at the last mile.

RBIH whitepaper: Gender and finance in India

MSC worked with the Reserve Bank Innovation Hub (RBIH) on a whitepaper on “Gender and Finance in India” for its स्व-नारी (Swanari) program. The paper discusses the landscape of gender and finance in India and highlights the main gaps in gender. Its premise is that applying a gender lens to financial inclusion is essential to understand barriers women face around equal access, usage, and quality of financial services offered. The paper analyzes public data on gender gaps in savings, credit, insurance, and pensions. Using inputs from experts and stakeholders, it attempts to understand key gender-based barriers. The whitepaper arrives at crucial problem statements around access, usage, and quality of financial services for the Swanari program. It also shares some promising innovations, good practices, and stories of female users and financial services providers. The paper ends with a call to move “toward gender-intelligent banking” and shares critical enablers that could catalyze women’s financial inclusion.

Would a Business Correspondent Network Manager’s (BCNM’s) strategy to customize incentive structure change the agent business?

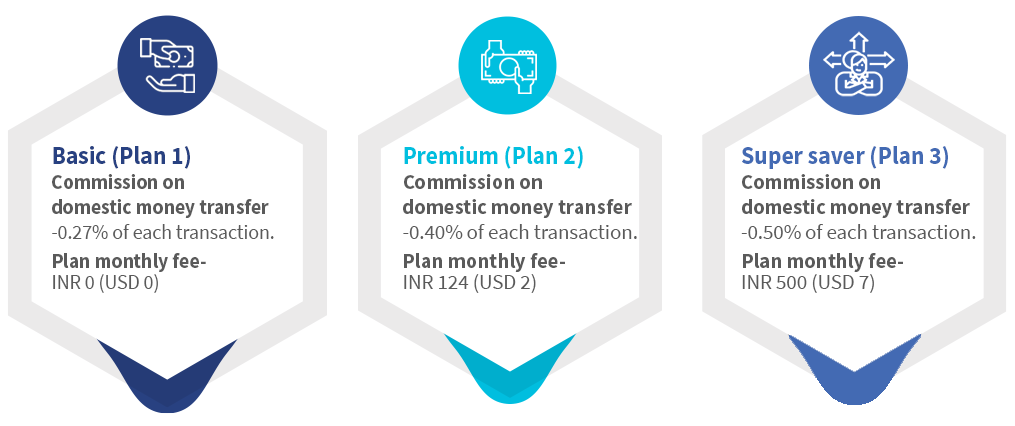

Eko India Financial Services is a new-age banking correspondent network manager (BCNM). It offered three progressive plans in its old incentive structure, shown in Figure 1, to more than 200,000 agents to take care of their business needs. The agents could choose the monthly plans which had different subscription charges based on their commission rates.

Figure 1: Old subscription plans offered by Eko to its agents (exclusive of Goods and Services Tax (GST))

Figure 1: Old subscription plans offered by Eko to its agents (exclusive of Goods and Services Tax (GST))

However, agents and their needs are different in India. Devnarayan Chaudhary, a Business Correspondent (BC) with Eko, operates from Vishwakarma Industrial Area near Jaipur, Rajasthan. He has been associated with Eko for more than six years now. He provides multiple services like domestic money transfers (DMT), cash withdrawals through the Aadhaar-enabled Payment System (AePS), bank balance inquiry, and utility payments through the Eko platform.

However, agents and their needs are different in India. Devnarayan Chaudhary, a Business Correspondent (BC) with Eko, operates from Vishwakarma Industrial Area near Jaipur, Rajasthan. He has been associated with Eko for more than six years now. He provides multiple services like domestic money transfers (DMT), cash withdrawals through the Aadhaar-enabled Payment System (AePS), bank balance inquiry, and utility payments through the Eko platform.

As Devnarayan’s outlet is close to an industrial area, his customer base primarily comprises migrant workers and truck drivers who send money to their families regularly using DMT services. Although his primary source of income comes from a cybercafe and cellphone selling shop, he is a well-performing BC agent on Eko’s platform. He conducts 80-100 transactions daily and earns between INR 30,000 to INR 40,000 (USD 400-500) per month by providing DMT services at his outlet.

Devnarayan has used Eko’s Supersaver plan till now. He paid INR 500 (USD 7) monthly and received a commission of 0.50% of the transaction value each time he transacted through the portal. While he was satisfied and earning well with his existing plan, he wanted more.

In contrast, Dharm Raj, another agent with Eko for three years. He operates from Samastipur, Bihar, and faces a unique set of challenges with Eko’s plans. He mainly serves beneficiaries of various government schemes. They come to his outlet to withdraw cash through AePS.

In contrast, Dharm Raj, another agent with Eko for three years. He operates from Samastipur, Bihar, and faces a unique set of challenges with Eko’s plans. He mainly serves beneficiaries of various government schemes. They come to his outlet to withdraw cash through AePS.

He conducts three to four transactions daily and earns between INR 1,000-2,000 (USD 12-20) in a month, using Eko’s Basic plan. Like Devnarayan, Dharm Raj’s primary source of income is a cybercafe.

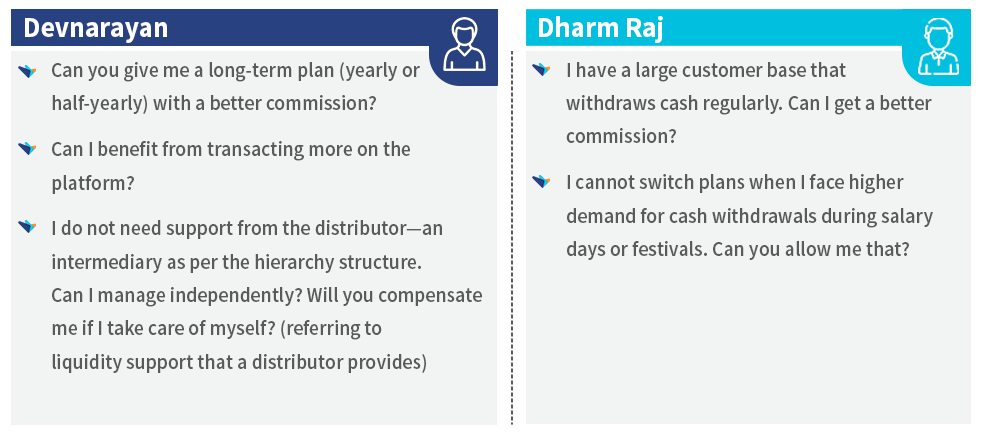

Agents like Devnarayan and Dharm Raj face multiple challenges around the incentives received as an agent. They have varied key demands, listed in Figure 2.

Agents have a choice. Faced with low revenues, agents often reduce or eliminate transactions on a platform and move to competitors’ platforms that offer higher commissions and easy options to switch. Such departures can reduce the usage of the platform and impact Eko’s business model, which is built around agent-assisted use. In India, the DMT and AePS market has become highly contested of late. Many nimble players have entered the market and lured agents with competitive services like higher commission, better customer support, and more robust field support. This competition has reduced the barriers to switching from one platform to another with lower setup costs and on-boarding requirements.

Agents have a choice. Faced with low revenues, agents often reduce or eliminate transactions on a platform and move to competitors’ platforms that offer higher commissions and easy options to switch. Such departures can reduce the usage of the platform and impact Eko’s business model, which is built around agent-assisted use. In India, the DMT and AePS market has become highly contested of late. Many nimble players have entered the market and lured agents with competitive services like higher commission, better customer support, and more robust field support. This competition has reduced the barriers to switching from one platform to another with lower setup costs and on-boarding requirements.

Thus, a growing BCNM like Eko must set the prices that provide value to their last-mile agents for higher usage and motivation.

Reinventing the existing incentive strategy: Addressing the challenges faced by agents

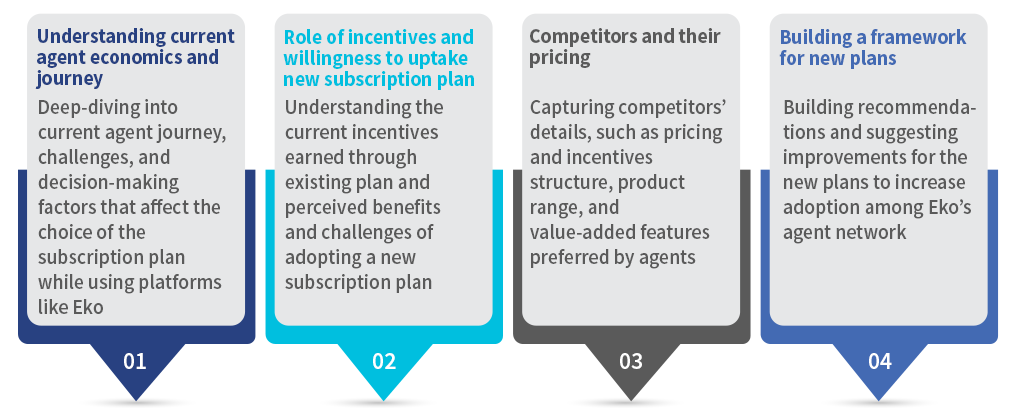

Eko cannot follow a cookie-cutter approach to address its agents’ varied needs and requirements. Thus, it decided to remodel its existing subscription plans to meet the needs of different agents. Eko designed a new set of plans based on the information and data in its extensive “agent transaction data bank” to address its agents’ needs. MSC (MicroSave Consulting) conducted an assessment to understand the agents’ perceptions around these new plans. The assessment focused on:

Figure 3: Focus of the assessment conducted by MSC

Figure 3: Focus of the assessment conducted by MSC

After completing the assessment, MSC recommended the “Good-Better-Best (GBB) framework” for improvements to the subscription plans, which would address the challenges faced by agents like Devnarayan and Dharm. The GBB framework helps Eko design a strategy that:

- Provides variable incentives for agents who have different turnovers, use specific services, or value features like longevity, subscription price, and commission value of the plans differently;

- Introduces plans with minimal entry barriers for all the existing and new price-sensitive agents who adopt Eko; and

- Enhances the suite of value-added features for high-potential agents.

GBB facilitated a subscription model that works as a tool to build solid relationships between Eko and its agents. Moreover, the model provides a seamless and sustained brand experience.

A sneak peek at the GBB framework for Eko

GBB takes a holistic approach to a solution to cater to differentiated needs and the value of differently-priced subscription plans for agents.

Figure 4: The GBB approach suggested by MSC, Source: Harvard Business Review

Figure 4: The GBB approach suggested by MSC, Source: Harvard Business Review

What implementing GBB means for the agents and Eko

Based on this recommended approach, Eko tweaked its plans to improve the overall incentives it provides agents to suit agent-specific needs better. The new plans have changed how an agent chooses a subscription plan.

- Now, Devnarayan can choose plans with extended validity. He chooses a 365-day plan and does not bother with monthly payments.

- Dharm Raj earns a higher income on cash withdrawals through AePS in his village. His overall earnings have also increased. He can now switch plans on specific days when customers receive subsidies. His outlet sees a high volume of transactions.

Other Eko agents can offer additional services through Eko and thus met a broader range of customer needs and serve more customers. Furthermore, the new scheme provides multiple options to rebalance, and even add e-value through UPI, which reduces their dependence on distributors. The option without distributors now offers a higher commission to agents like Devnarayan.

These changes supported different agents by offering more flexibility, convenience, and higher revenue due to increased incentives across multiple products and services. Since the launch of the scheme in July 2021, more than 68% of agents have taken up the new plans. Eko has increased revenue and provided new sources of earnings to its extensive agent network through the platform.

What the new pricing strategy means for Eko’s future

The changes Eko introduced have supported the increase in agent incentives. But will the new scheme prevent agents like Devnarayan or Dharm Raj from moving to competitors offering them other unique benefits? We cannot say for sure.

With an increasing number of BCNMs in an ecosystem that provides agents with higher increasing incentives, competing providers will find it challenging to maintain agent stickiness. Similarly, these will not be the last set of plans Eko launches to support its agent network. Every time the agent incentives and plans are redesigned or changed, the Good-Better-Best framework and its principles can guide Eko.

Increased competition will influence the BCNM ecosystem through new product features, convenience, and commissions. We expect things to heat up—for the better—as we move forward with new emerging business models, rapid technological innovations, state initiatives, and more players entering the market.

Women’s agent network—the missing link in India’s financial inclusion story: A supply-side perspective

Over the past decade, business correspondents (BC) agent outlets have grown by nearly 45% CAGR compared to bank branches, which grew at 6.4%. However, female BC agents represent only 10% of the BC agent network. Mounting evidence points to increased financial activity by women if they transact with a female BC agent.

This note discusses a supply-side perspective on expanding women’s agent network in India, based on a survey with private BC network managers. We discuss the efforts made in several fronts to recruit and include more female BC agents and the challenges supply-side providers face in the process. Based on the study, we conclude with recommendations to increase understanding and appreciation among service providers about gender policies and practices and their effect on cash-in-cash-out (CICO) operations.

Are we over-selling start-ups as a career option?

A little personal history

In 1983, as I was training to be a chartered accountant, I worked with Peter Risdon and Lord Trevor-Roper on a start-up to challenge the optician’s monopoly on reading glasses in the UK. In those days, basic reading glasses cost more than £40 a pair – even though they could be imported for less than £1. Opticians asserted that people needed an eye test to identify the appropriate reading glasses. This was clearly wrong, and as a result of our “For Eyes” start-up, the Optician’s Act of 1958 was amended. As a result, in the UK, as in the rest of the world, anyone can buy reading glasses for £1.

We were naïve entrepreneurs and quickly ran into the classic start-up’s liquidity problem as we had to pay suppliers before we had the cash from the roaring sales at our modest shop in Clerkenwell in London. After much heart-searching, I pitched our business to my Father and secured a loan of £10,000 – no small sum. We struggled on, refused a take-over bid (I said we were naïve), and eventually For Eyes collapsed, and I had to return to my Father empty-handed, only able to offer apologies.

Harsh realities facing start-ups across the globe

This story is common amongst start-ups across the globe – friends and family are roped in to finance aspirations and dreams of young wannabe entrepreneurs with big plans and small bank balances. In the last decade, we have lionized these entrepreneurs. We have placed them on pedestals and sold the idea of building “unicorn” tech start-up companies as part of the digital revolution. Some are realizing those dreams, and many are developing valuable products and services to make our lives more convenient.

But the success stories are not the norm … The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM)’s research shows that there are “about 300 million people who are trying to start 150 million businesses worldwide … there are about 50 million new businesses each year”. So, globally, there are roughly 137,000 start-ups daily … but around 120,000 businesses close each and every day.

For every single success story, there are around ten failures. Investopedia notes that “in 2019, the failure rate of start-ups was around 90%.” It highlights that “reasons for failure include money running out, being in the wrong market, a lack of research, bad partnerships, ineffective marketing, not being an expert in the industry, and particularly for, tech start-ups, wrong timing.”

A recent NetshopISP article noted that each year, “1.35 million [start-up] businesses are tech-related.”

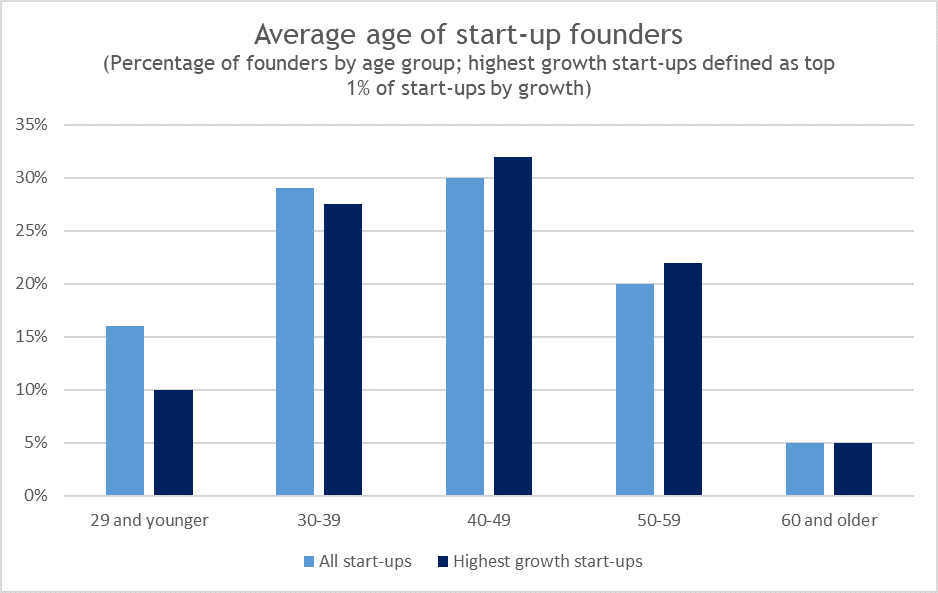

The popular image of tech start-ups is of geeky students operating out of their dorms – but these are less common and indeed less successful than their more mature, experienced counterparts. US Census Bureau and MIT research showed that tech entrepreneurs aged 60 years are nearly four times more likely to found a successful start-up compared to entrepreneurs who are in their mid-20s. The average age of a successful start-up founder is 45.

StartupsUK highlights a similar pattern, noting that, “Most small business employer owners and co-owners fall into the 35 to 44 (25%), 45 to 54 (31%) and 55 to 64 (26%) age categories. The proportion in older cohorts is much smaller; just 7% over 65.”

Source: Age and high growth entrepreneurship – Pierre Azoulay et al 2018

MSC’s experience with start-ups in Asia

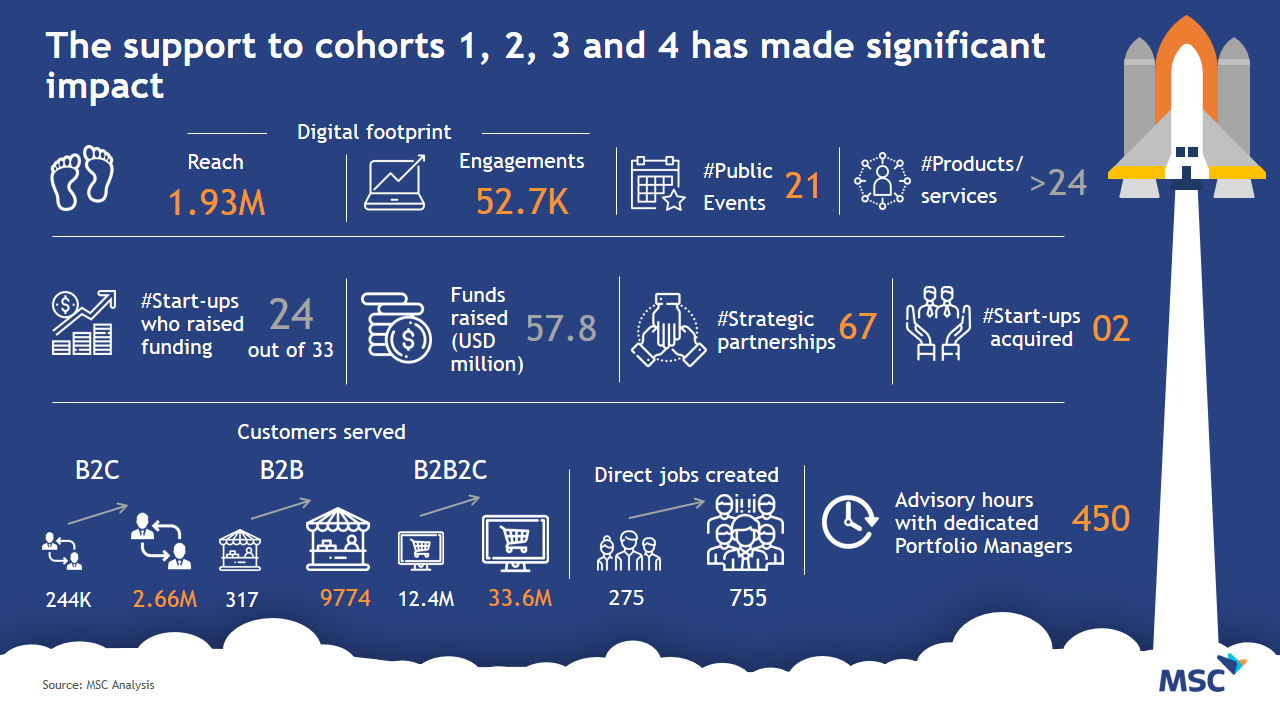

MSC’s acceleration labs and related work in India, Bangladesh, and Vietnam nurture start-ups in their growth stage to deliver appropriate solutions to serve low- and moderate-income (LMI) people. Due to the extensive support that these start-ups receive from the lab, their probability of success is high. Though not representative of the whole market, these start-ups highlight interesting perspectives and data on the start-up universe.

1. Selection funnel – the blessed 4%

- There are too many ideas, but very few of them were selected for support through the labs. MSC-supported acceleration programs have already received over 1,100 applications. However, only 44 (4%) of those start-ups have received or are receiving support.

2. Age of entrepreneurs

- In India, the Business Standard reports, “The workforce in the age group of 45-54 years (37 percent) are hesitant to start their own business as compared to the workforce in the age group of 25-34 years (72 percent) and 35-44 years (61 percent).” So it is unsurprisingly perhaps that the average age of the founders in our cohorts in India is 34.5 years – experience makes an important difference. However, we have also seen a few young co-founders setting up start-ups. However, most of the start-ups have co-founders with complementary capabilities to mitigate the risk of failures and add years to their cumulative experience as they steer the start-up.

3. How many have borrowed from family and friends? How many still owe family and friends?

- Almost all the start-ups in our cohorts have taken money from friends and family – unsurprising considering the relatively early stage of their ventures. It is difficult (and sensitive) to ascertain if they still owe money to their friends and families. However, one-third of the cohort start-ups have already raised money from institutional investors – we can safely assume that this could help them return, at least part, some of their borrowings from friends and family.

4. Type of support-services provided

- Start-up founders and their teams build digital products. However, it requires an extensive understanding of the LMI segment to ensure user value. Our labs support founders to understand their customer segment better and design products with a better market fit. This ensures quicker adoption and higher usage of the products and increases the success rate of the start-up. For example, Lakshya is a digital savings platform that provides access to formal savings and insurance to India’s LMI segments. The lab helped them with customer segmentation and enabled Lakshya to design financial products that catalyze the economic well-being of their customers.

- The rise of digital engagement has enabled founders to launch products with near real-time decision-making capability on processes like customer onboarding, underwriting, payments, and so on. In this context, start-ups must have a strategy to deal with poor quality of data architecture, management, and analytics. Our labs are mentoring start-ups to formulate robust strategies to develop and implement efficient data-centric processes. Finarkein Analytics focuses on simplifying the information value chain through its unique and innovative data analytics solution. Our lab supported them to understand the account aggregator data ecosystem in India, streamline their current processes, and formulate a robust pricing strategy for their services.

- Go-to-market is key to scaling up product adoption and usage. Many early-stage start-ups suffer despite achieving product-market fit as they struggle to onboard the right customers to use the product. Insufficient product traction directly impacts the investment cycles and becomes a potential risk for failure. Our labs help start-ups identify channels to reach LMI customers efficiently and collect feedback from these users. This enables founders to refine the product and achieve a larger customer base. Fundfina is a digital lending platform providing access to formal credit to micro and small enterprises (MSEs) in India. The lab’s support helped them understand the segment-specific behavior and craft a marketing strategy to reach 10 million small enterprises in the next five years.

- Undoubtedly collaboration is key to startup success. Businesses with innovative products and limited resources must find partners to scale efficiently. Through our labs, startups get a chance to interact and work with partners/enablers like non-banking financial companies (NBFCs), farmer producer organizations (FPOs), corporates, policymakers, banks, and so on in the ecosystem. This results in quick scaling, increased efficiencies, and better unit economics, which directly contributes to the founder’s success. Whrrl, an agritech startup from our cohort uses a blockchain-based disruptive financing model to fund farmers. Our lab has enabled them to partner with various FPOs, warehouses, and agri-institutions to engage farmers.

These challenges were amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic.

These trials and travails reflect the challenges that even the most successful start-ups face … and, despite being in the carefully selected top 4% of start-ups, and despite the extensive support from the labs, many struggle to survive.

The concern

Despite this, start-ups are promoted as a credible career option for young people more than ever before. One colleague received a mail from his son’s high school promoting the idea of start-ups as a career. And the papers are full of success stories, but rarely mention the many more failures. Society seems to favor glorified stories on young adults making it big, without going into too many details of the struggles involved. We risk encouraging millions of, often naïve, aspirant entrepreneurs to start a business when they are least equipped – financially and in terms of experience – to do so. We may well be doing them a disservice by hyping tech start-ups and selling the unicorn dream. Furthermore, as I can attest from personal experience, the need for financial support drives young, poorly resourced entrepreneurs to borrow from their families and friends. In >90% of cases, these loans will not be repaid from the start-up, leaving important relationships fractured and damaged. Is this a price worth paying?

Putting India’s demographic dividend to work: Skill development for a digital economy

Jyoti Chaudhary has a diploma in information technology from the Government Girls Polytechnic institute in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh. When she sought employment, Jyoti quickly realized her three-year technical education was inadequate in the job market. Her teacher advised her to pursue another three-year degree to become an engineer, after which the likelihood of securing a job was better—at least on paper.

Jyoti’s story is similar to millions of other young people in India. Faced with low prospects of a job or none at all, youth who can afford to continue their studies choose to get another degree or certification, which delays their entry into the workforce. The time and money spent to acquire additional degrees without a corresponding increase in job prospects prove costly. Indeed, as the BBC notes, “the more educated the person is, the more likely it is they will remain jobless and unwilling to take up low-paying and precarious informal jobs.”

This blog discusses the changing nature of employment and provides recommendations to improve current skilling programs.

The demand side: The informal economy continues to dominate the employment market

While India has succeeded in moving the bulk of the labor force away from the unproductive agriculture sector, most jobs remain limited to the economy’s informal sector. The National Sample Survey Organization (NSSO) and data from the Periodic Labor Force Survey (PLFS) indicate that between 1999 and 2019, most of the labor force that moved out of agriculture (16%) was absorbed in the construction sector (11%). PLFS 2019-20 notes that informal enterprises employed 69.5% of the labor force. Informal enterprises include self-employment and micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs).

Entrepreneurship as self-employment

Except for a few years, India’s economy grew at more than 7% annually between 2003 and 2018. This growth earned it the tag of the fastest-growing major economy globally. Even as the country clocked impressive growth numbers, economists were worried about one anomaly—jobless growth.

In 2019-20, the share of salaried employment in the country fell from 21.9% to 21.3% in the previous year. The Centre for Monitoring the Indian Economy (CMIE) explained that the stagnation in salaried jobs and the sharp rise in entrepreneurship indicated that self-employed people drive much of India’s entrepreneurial growth. It further notes, “Entrepreneurship is often a desperate escape from unemployment rather than an initiative to create jobs. An increase in entrepreneurship of the kind India has been witnessing since 2016-17 is evidently not the kind that creates salaried jobs.”

Therefore, the most likely scenario is not jobs created in large companies that employ hundreds of people. Instead, we will see economic activity generated by exchanging products and services between entrepreneurs (and MSMEs) and freelancers. For example, a weaver manufacturing artisanal sarees will enlist the help of a freelance photographer to create a portfolio of her products and a web designer to create an e-commerce site.

The role of digital India and the COVID-19 pandemic

Between 2010 and 2020, India saw a remarkable rise in the adoption of digital technologies aided by the availability of cheap data, low-cost mobile phones, and the digital transformation of public services, technology infrastructure, and citizen empowerment architecture under the Digital India program.

In 2017, freelance workers from India had a 24% share of the online global gig economy. These numbers grew further due to the drop in full-time jobs and the rise of remote work during the pandemic. Both factors helped create a favorable perception of freelance work.

This trend is validated among the alumni of the grassroots organization, Medha. For over a decade, Medha has helped prepare youth for life after school. In a recent study, 70% of Medha’s alumni indicated they were eager to work as freelancers. However, they felt they needed more information about opportunities and skills to thrive as freelancers and handholding support to access the market.

To summarize, on the demand side, economic opportunities will continue to emerge in the informal sector, the MSME sector, and among individuals who offer services as freelancers in the gig economy.

The supply side: Skilling infrastructure in India

Skilling in India is a massive challenge because of the wide rift between the traditional primary and secondary education systems. Over the past decade, however, the country has made much progress in improving its vocational and technical education infrastructure. Technical institutions now cover polytechnics and engineering colleges (for undergraduate and graduate courses).

Another focus has been the government-led skilling program (short-term courses of 2-6 months each) to certify participants, mostly school dropouts, in one skill or award a skill certification for prior knowledge. This is an attempt to create a cadre of skilled workers and reduce the challenges of information asymmetry by assuring employers of the skill levels of potential employees. However, these efforts have led to limited results in a scenario where formal jobs in the economy are rare.

Building skills for the digital economy

We recommend the government expand the current skilling architecture in the country to address the fact that most jobs in the short to medium term will come from the MSMEs in the form of self-employment, as discussed above. The nature of most jobs would also change to task-based and micro-work that focuses on a single step of much longer value chains with multiple players.

The survey of youth aspirations by ORF mentions information asymmetry, lack of guidance, and work experience as factors that impede young people’s ability to access jobs and economic opportunities. Our proposed approach builds on students’ core technical skills to help them thrive in the digital economy.

It seeks to reduce information asymmetry—by developing processes and capabilities that improve the discovery of employment opportunities and reduce information gaps between employers and potential employees. The proposed approach will guide young people on their path to upward economic mobility.

The proposed approach is divided into three parts:

1. Integration of 21st-century skills into the skilling systems: Skill development programs must prepare students to navigate the digital economy. The components of such a curriculum are as follows:

- The 4Cs: critical thinking, creative pitching, collaboration, and communication—provide students with the skills needed to survive and thrive in the modern work environment.

- Modern-day literacy with the “become an entrepreneur” approach: includes modules on accessing information over the web, basic financial literacy, understanding markets, using social media and digital platforms. Students can then manage finances, identify potential marketplaces, and market their work.

- Essential life skills: flexibility, self-awareness, leadership, and people skills prepare students for life after school. These skills put participants on the track for lifelong learning and development.

2. Provision for on-demand guidance and mentorship models for individuals: MSC’s research on entrepreneurship and MSME development points to the outsized impact of access to mentorship on an entrepreneur’s performance. Medha’s Swarambh program—to skill freelancers—connects mentors with aspiring students. Customized and on-demand guidance helps create a supportive ecosystem, enabling entrepreneurs to navigate their work.

The current vocational and technical training infrastructure might serve as support centers providing ongoing advice to entrepreneurs regarding access to technology, business opportunities, financial management, and compliance, among other areas. The recent announcement of the Digital Ecosystem for Skilling and Livelihoods in the Finance Bill (Union Budget) for 2022–23 can potentially act as a technical backbone to scale this idea.

3. Address the digital divide to enable youth to access opportunities in the digital economy

While the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted opportunities for students in the digital economy, it also exacerbated the digital divide in India. Any program to enable skilling for a digital economy should account for the wide disparity in the ownership of mobile phones and computers among the low- and middle-income groups. Skilling programs should avoid a one-size-fits-all approach. Instead, these should subsidize the cost of digital assets and data plans for students, wherever applicable, to enable them to access digital programs. Similar efforts are needed to overcome the gendered access to education, skills, and digital assets.

Skilling the 13 million youngsters that join the workforce in India every year is an uphill task, especially given the shortcomings of its education system. While fixing them remains the top priority of the country, they are beyond the scope of this blog. In the short term, we need to deploy large-scale efforts to equip the skilling programs with modules on 21st-century skills and fortify the necessary infrastructure for mentoring the youth. If done correctly and jointly, it can help India realize the potential of its demographic dividend.