Many thanks to Chris Maclay, Director of Youth Employment at MercyCorps for his time and viewpoints regarding the Jobtech ecosystem in Africa.

An old African proverb proclaims, “It is the young trees that make up the forest.” Africa’s youth will determine its future. The next several years will be decisive in determining how successful we are in caring for the younger trees to help ensure they grow into a vibrant forest. In the previous blog, we outlined some systemic constraints hindering the sustainability and scalability of job matching platforms in Africa. With 70% of the youth population in Africa under 30, stakeholders must seize the opportunity to onboard youth to digital platforms transparently, provide them with consistent and reliable work, and ultimately allow platforms to serve as a roadmap to formalization. Below we have provided recommendations as to how this can be accomplished.

Recommendations

Build the ecosystem from scratch: The digital platform ecosystem in Africa seems to be modelled on digital platforms in developed countries despite the significant differences in the economic models. The “winner takes all” approach, in the absence of adequate labor protections, can actively harm the workers it seeks to benefit, as many platforms aim to run down their prices which negatively impacts workers’ wages, and their trust in the platforms. There is, therefore, a need to develop an ecosystem that can identify and respond to the unique challenges of the African continent regarding youth employment. The Jobtech Alliance, hosted by MercyCorps serves as a place for startup platforms and development practitioners to share best practices and disseminate knowledge in the space. The sharing of information within and among the members will enable stakeholders to address the systemic constraints and facilitate a double bottom line impact – both in terms of running profitable, scalable businesses and providing economic livelihoods to its workers.

Don’t put the cart before the horse: There is little doubt that digital job matching platforms have the potential to positively impact [youth] employment in Africa. However, before such platforms can catalyze this long-anticipated employment boost, they must understand the markets in which they operate. There has been much talk in the development world about the unfair conditions to which platform workers are subject – lack of employment contracts, social protection benefits, labor regulations, etc. In fact, foundations, such as Fairwork, have established fair work principles for gig workers (which include social security benefits, gratuity, minimum wage protection, and working hours), in hopes of raising their working standards globally through transparent evaluation of platforms. There is no doubt that such initiatives are necessary to raise awareness, however, it is important to maintain a balance between the platform’s viability (through the provision of economic opportunities to workers) and its responsibility to ensure fair working conditions. Benefits remain a costly proposition for platforms. Given the negative effects that youth employment has on the African economy, as a whole, and the historical challenges of worker protection, governments should be involved in sharing the costs of worker protections with the platforms.

Gig workers have expressed more interest in consistent work and the value they ascribe the flexibility, than social protection benefits and workers’ rights. The flexibility and access that platforms provide to low- and middle-income populations initially outweighs the need for such protections, which most certainly are not available in non-platform mediated informal markets.

Build Worker Centric Platforms: A digital job matching platform is only as successful as its workers. Therefore, despite the drive to maximize profit and reduce costs, platforms should be built putting their workers at the forefront – in the long-run this will create brand-value, and thus loyalty of both gig workers and those that hire them. Platforms that offer low-skilled, standardized work, which are the choice of many informal workers in Africa, run the highest risk of designing platforms that give little bargaining power to workers, simply due to the commoditized nature of the work itself. The importance of worker centricity in platform design and execution has been highlighted by organizations like the ILO. The ILO examines how the architecture or business model design of labor platforms directly impacts worker well-being in terms of increasing worker agency on the platform, particularly through greater data transparency that can improve worker bargaining. The role of imbalanced supply and demand incentives or rewards, information asymmetry, inability of workers to coalesce and certain labor management mechanisms put workers at an inherent disadvantage and often results in high attrition rates. Other resources on this topic include a report by the Institute For The Future on Positive Platforms which outline positive design principle that platform designers should consider when designing and operating platforms.

Caribou Digital, as part of its work with the Partnership for Finance in Digital Africa, has done work in this area in regards to advocating for platform payment systems that reduce friction around worker payouts, revisiting withdrawal fees, looking at the timing of payouts and the implications of pay-to-promote policies. Platforms should also consider the role that financial services could play in the lives of its workers and use the platform to facilitate financial inclusion. Several platforms have begun offering financial services to their workers including insurance and credit for the benefit of both their workers (retention, ability to grow quickly etc.) and their core business (diversifying revenue streams). In fact in 2019, MSC, using human centric design principles, collaborated with Britam to design a pay-as-you-go personal accident coverage for Lynk’s workers.

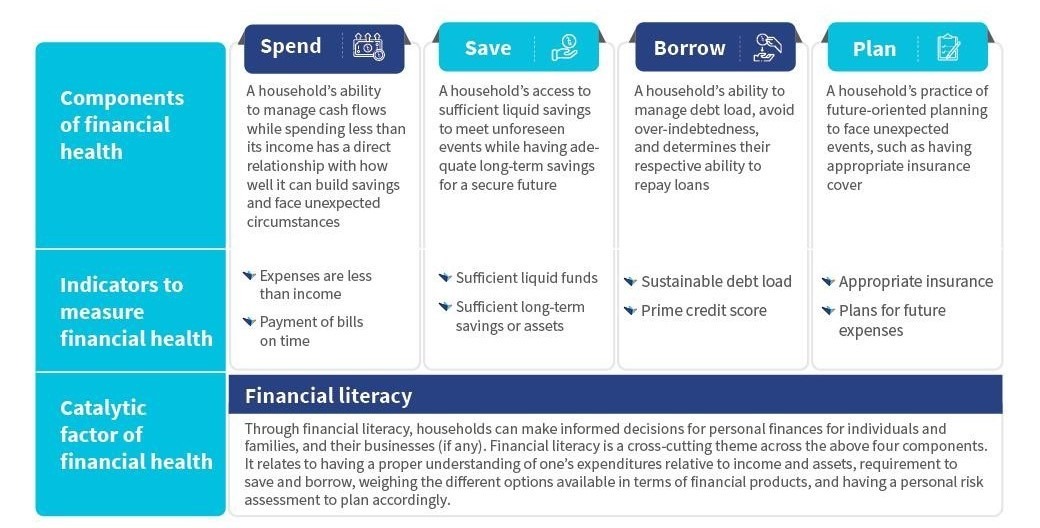

Invest in platform-led upskilling: Platform creators must realize the importance and value of imparting skills and training to small scale vendors and/or individuals who have joined the platform. As the skills gap in Africa is large, the training that platforms provide, including soft skills, online training and financial literacy, has the potential to result in a stronger and more capable workforce with portable skills. Although it requires an investment, and weighs heavily on the platform itself, governments and donors alike should step in to subsidize or fund such programs. For example, Lynk has experimented with different training mediums to see which resonate most with their workers. Lynk’s application “Lynk Lounge,” contains videos and text training modules on various topics, such as how to create an appealing profile or provide good customer service, as well as vertical-specific tips. MAX, an on-demand motorcycle-hailing and delivery platform in Nigeria, sends in-app messages to drivers to reiterate and reinforce lessons taught during face-to-face onboarding training sessions. A platform’s investment in its workforce is not a sunk cost as it will contribute to higher retention rates and a better market reputation, which is paramount at this time when environmental, social and governance (ESG) companies are increasingly valued and valuable.

Conclusion

With the advent of technology and the ubiquitous use of cell phones and the Internet in Africa, digital job matching platforms are here to stay. We can look at them as a necessary evil in 21st century life, or rather ensure they are filling the role for which they are optimally designed: that is, in many cases, providing job discovery and work opportunities to informal workers while ideally serving as an “onramp to formalization.” There is no one business model fits all approach to platform design and execution. Therefore, by taking market nuances into account, and putting the interests of its workers at the center, platforms in African markets will not only survive, but thrive.