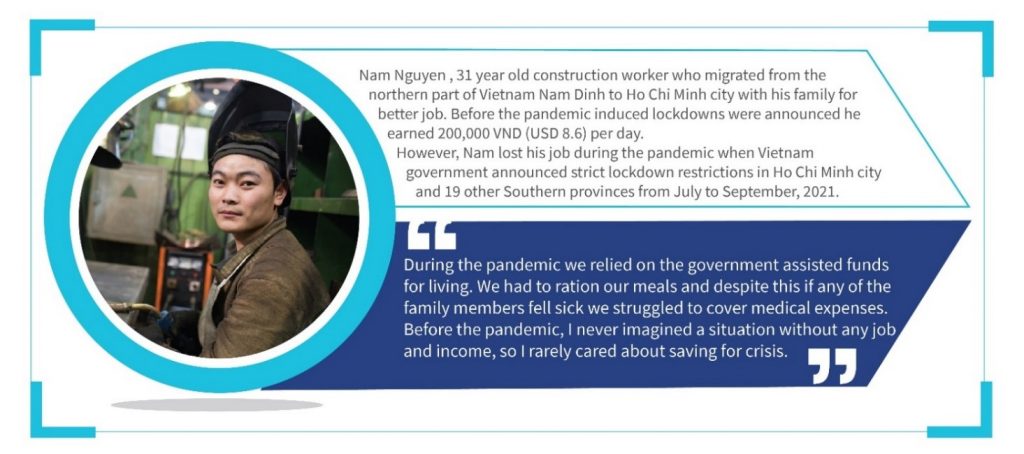

Nam Nguyen belongs to an estimated one million households in Ho Chi Minh City who had to rely on government support to get through the COVID-19 lockdown. These households represent Vietnam’s low- and moderate-income (LMI) community and comprise farmers, students, daily-wage workers, and nano- and micro-business owners. They are among 70% of Vietnam’s 95 million people earning about USD 2–10 per day.

The third and fourth waves of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021 severely affected Vietnam and laid bare the vulnerabilities of LMI. It highlighted the need to have a pool of savings to tide them through financial shocks. Construction worker Nam learned this the hard way.

How do LMI people in Vietnam save their money?

Saving after managing expenses remains a priority for LMI people in Vietnam who aspire to lead a better life, absorb income shocks, and strengthen financial resilience. However, ~69% of adults in Vietnam remain un(der)banked and have limited or no access to financial services.

Access to formal savings has been far from uniform, particularly in rural areas. As a result, most LMI people still prefer to save outside the formal sector, using informal means such as keeping cash at home and saving with informal associations/ clubs.

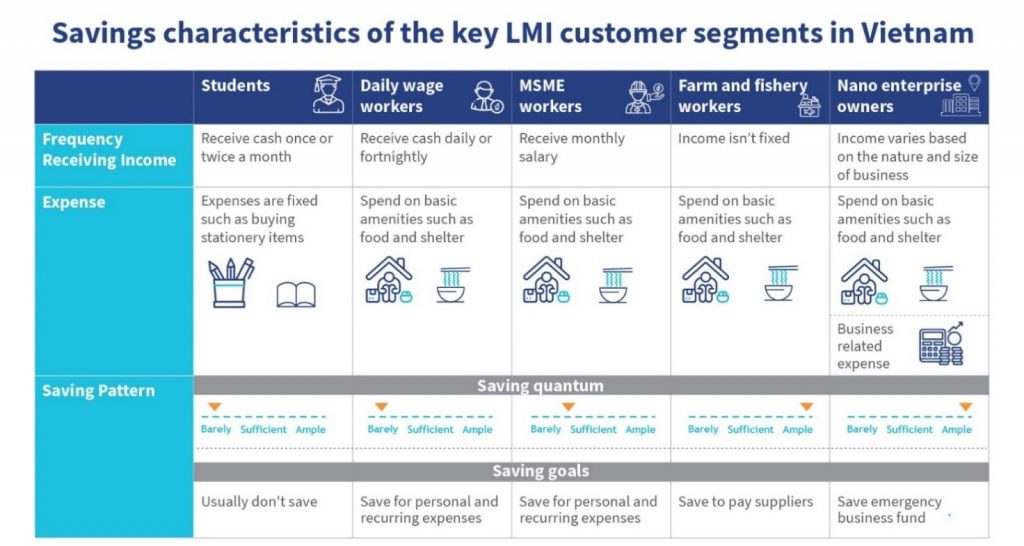

The figure below highlights the saving characteristics of Vietnam’s key LMI customer segments.

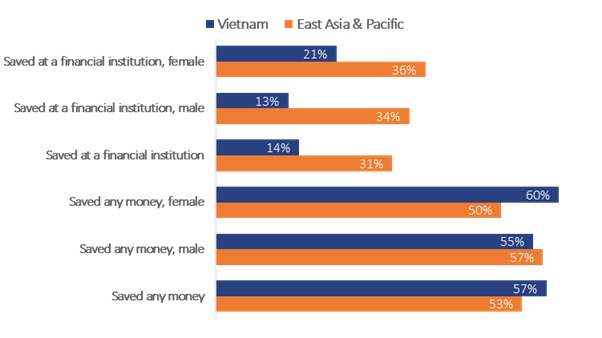

Figure 1: World Bank’s comparison of savings pattern between Vietnam and East Asia & Pacific in 2018

Figure 2: Savings characteristics of Vietnam’s key LMI customer segments

What challenges do LMI people face in saving their money?

LMI customer segments in Vietnam recognize that savings are essential for financial security. However, they face multiple challenges:

Small incomes make it hard to save. In rural Vietnam, the average monthly income per capita is around USD 152, while the average monthly expenditure is USD 105. So at the most, they can save USD 47 a month, even if they cut out all discretionary spending. In addition, most LMI people’s income is cash-based, sporadic, and unpredictable, which means that they sometimes have to resort to emergency borrowing, making it even more of a challenge to save regularly. Moreover, those who do save prefer to save in cash because it is convenient and easily accessible.

The result is that many small savers keep their money in informal channels, like “Ho/Hui,” a rotating credit and savings association. However, these can be risky as there have been cases of frauds where participants have lost their money.

Another challenge is the lack of access to bank branches. For every 100,000 people in Vietnam, there are only four commercial bank branches. Visiting far-off branches is costly, involving transportation and opportunity costs during business hours. Many small business owners also want to withdraw their money at short notice, which they cannot do if the bank branch is far off. Moreover, to open an account, customers have to travel to the bank multiple times —to submit documentation, collect a passbook, and so on. For most LMI people, the costs involved are not worth the effort.

Furthermore, Vietnamese commercial banks only offer one-size-fits-all saving products that do not meet the varying needs of the LMI community. For instance, most commercial banks require a minimum of VND 1,000,000 (~USD 44) to open a savings account. The weekly savings of the LMI people is nowhere near this amount.

Most commercial banks prefer middle and upper-class urban consumers. These banks do not target the different LMI customer segments as they don’t save large enough sums of money to cover the costs of acquiring and maintaining them as clients.

Some state-run financial institutions, including the Vietnam Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development, the Vietnam Bank for Social Policies (VBSP), and the People’s Credit Fund, offer savings and credit products for people with lower incomes. However, barring VBSP, these institutions have not had large-scale success owing to compulsory savings, lengthy and complex processes, and reliance on physical distribution channels.

Three-pronged solution

MSC is working with organizations in developing countries to help LMI people ease into a more robust savings behavior and improve their financial health. The following elements are required to foster small savings for LMI people in Vietnam using technology, smart product design, and innovative distribution platforms:

1. Product features designed to match the lifestyle and needs of LMI people

Such accounts should be simple to open and maintain, and customers should be able to access their money easily. In addition, there should be no requirements for a minimum balance to be maintained or any lock-in period, which is a big concern for small savers.

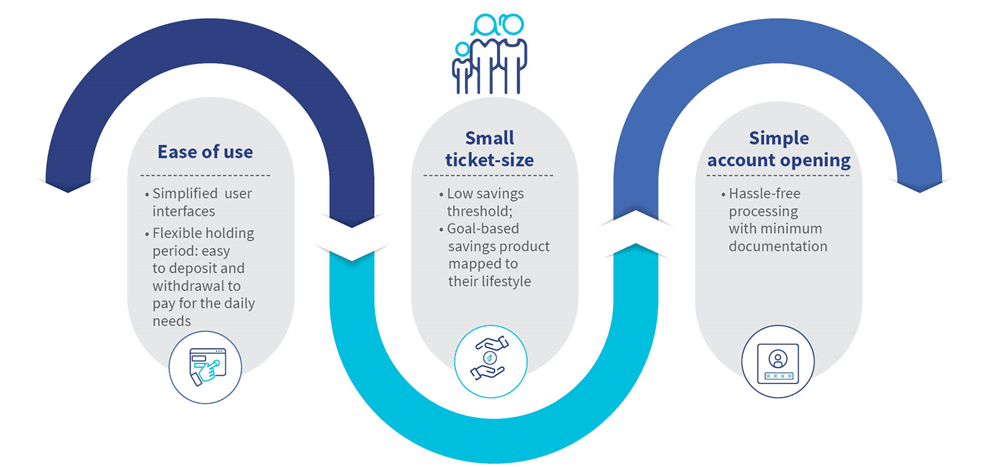

Figure 3: Key characteristics of an ideal micro-savings product

A digital savings account can provide these features by offering a simple user interface with clear and short instructions that enable users to deposit and withdraw money easily. These digital accounts can have an inbuilt feature that gives customers periodic reminders or “nudges” to set aside money, even as low as VND 20,000 (~USD 1) a day. Offering a goal-based product, such as saving for a child’s education, can also encourage savings.

MSC has helped create such a small-savings product in Bangladesh. In 2019, MSC partnered with Shakti Foundation, a micro-finance institution, to develop voluntary savings products targeting women. The Family Savings and Lakhpati Savings products are available across Shakti’s 356 branches and have helped more than 350,000 women save money.

Shakti’s women customers do not need to maintain a minimum balance with no lock-in. It encourages savers to set a goal and gives them frequent reminders on their feature phones to add as little as BDT 100 (~USD 1). Users also get information about their account balance on their phones, saving them the trouble of going to a branch.

2. Phygital distribution channels to democratize savings

With innovations in technology and finance, traditional banks can tap into new channels to bring micro-savings to LMI people. These include digital wallet providers, e-commerce platforms, or “super apps” such as MoMo, Grab, Zalo, and Shopee, which have amassed millions of customers in Vietnam lately. These technology-led platforms will reduce the cost of acquiring new customers by accepting documentation online or via a phone and doing an eKYC. Moreover, super app players can market savings products to a strong base of millions of LMI users much faster.

Saving through an app is easier and cheaper for individuals. For instance, users can deposit or withdraw money from their accounts in a few seconds using biometrics or one-time password verification. Meanwhile, the technology platforms also benefit by acquiring new customers and eventually cross-sell them other products and services.

MSC is working with a leading FinTech in Vietnam to offer a digitally-enabled savings solution to enable its users to put small amounts of money aside when they can. The solution provides goal-based savings mapped to the users’ lifestyle, interest rates at par with incumbents/banks (~5%), easy (digital) access and monitoring, and withdrawal flexibility.

3. Agent networks to tap into rural, underserved areas

Agent networks are essential in a context where a significant customer base is rural, underbanked, and yet to try out technology-based, self-initiated transactions.

Agent networks have expanded access to and usage of financial services in Bangladesh, Kenya, and India. For instance, Bangladesh launched its mobile financial services (MFS) in 2011 and now has 1.1 million agents that serve 110 million customers. At present, 13 companies offer MFS to 60% of the adult population. In addition, more than 11,320 agent banking outlets serve 5.26 million customers.

In 2017, the state-run State Bank of Vietnam (SBV) piloted a ‘cash-in and cash-out’ agents program with MB Bank – Viettel, PGBank – Petrolimex sales points, and Vietcombank – MoMo. Vietnam, however, does not have a formal agent banking network, which will be critical as an intermediate stage in reaching out to and onboarding rural customers.

The National Financial Inclusion Strategy aims to develop and issue regulations on licensing and guiding the operation of banking agents. It also aims to facilitate non-bank organizations with a vast network or operating areas in rural and remote areas to become agents of banks.

The bottom-line

Savings is an essential tool that helps LMI people like Nam strengthen financial resilience. Collaboration among multiple stakeholders, including regulators, financial institutions, and financial-technology firms, is needed to digitize and simplify the savings journey for LMI people in Vietnam. MSC and Startup Vietnam Foundation (SVF) are driving one such multi-stakeholder partnership- the ‘CO4GROWTH’ accelerator program. We are supporting 35 startups under the program to develop innovative, technology-enabled solutions for the LMI people in Vietnam. We expect the regulatory sandbox for FinTechs approved by the Government of Vietnam in September 2021 to foster the development of new services, such as digital savings accounts for small savers. Meanwhile, service providers need to understand this opportunity and innovate —which, if done well, can lead to a win-win proposition for all.