Microenterprises in Vietnam account for more than 98% of the business, 40% of the GDP, and 50% of the total employment. The COVID-19-induced lockdown restrictions prompted many merchants to go digital by selling foods and drinks online through super apps. The “Innovate, Implement, Impact” or i3 Program, supported by the MetLife Foundation, creates opportunities for nano and microenterprises to go digital and “cashless.”

Watch our video for more updates on the i3 program in Vietnam.

Different yet similar — behavioral biases of low- and moderate-income people in Bangladesh and Vietnam

Macroeconomic differences and similarities

Source: Link

“We see the potential volume, but do we design profitable products for low-and moderate-income (LMI) people?”. MSC faces this question repeatedly in discussions with our clients across Asia and Africa – including our partners in Bangladesh and Vietnam under the MetLife Foundation-funded i3 program.

In these two blogs, we answer this question – Irrespective of the country you are in, these are key behavioral biases to keep in mind to create compelling, engaging, and profitable products for the mass market.

Worldwide, behavioral biases shape the needs, aspirations, and behaviors of people from low- and moderate-income (LMI) segments. These biases play a vital role in how people from these segments perceive, accept, and use financial products and services. This two-blog series covers Bangladesh and Vietnam. The first part highlights the macroeconomic and demographic differences and remarkable similarities between the two countries. The second part delves into the behavioral biases of the LMI segments which financial service providers (FSPs) need to keep in mind when designing products for them. Even though there are macro-level differences between these countries, their LMI segments show deep commonalities in behavioral biases toward financial services.

As part of the i3 program, MSC supports different stakeholders, including banks, FinTechs, microfinance institutions, wallet providers, and government departments in Bangladesh and Vietnam. MSC’s support helps these stakeholders understand and serve the needs and aspirations of the LMI segments and move them toward better financial health.

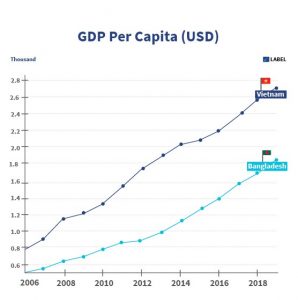

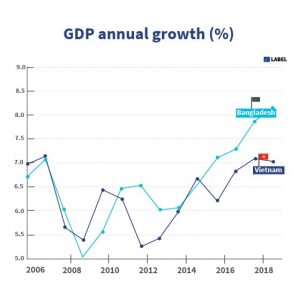

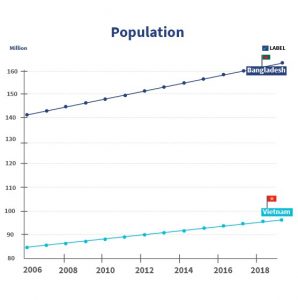

Let us start with the macro-economic and demographic data of these countries, highlighted in the graphs below.

Source: The World Bank Data—https://data.worldbank.org/

Demographics

With 165 million people, Bangladesh is around 70% more populous than Vietnam. In Bangladesh, the population density is five times that of Vietnam. However, close to 60% of their population lives in rural areas. Most of the migration to the cities happens because of unemployment and education.

Both the countries fare equally well on life expectancy—Bangladesh has a life expectancy of 73.6 years. In contrast, Vietnam has a life expectancy of 75.8 years. Bangladesh is a slightly younger country, with a median age of about 27 years compared to 32 years in Vietnam. While leading economies like Europe, the US, South Korea, and Japan are aging, Bangladesh and Vietnam have the advantage of a young working population. This demographic dividend offers a distinctive edge for the GDP of these countries in the future.

Fifty percent of the population of both countries comprises women, many of whom who want to work. For example, Bangladesh’s readymade garment (RMG) sector employs nearly 4 million people, mainly from the LMI segment, 60% of whom are women. Also, see this webinar on “Successful cash support payments to the most vulnerable: Lessons from Bangladesh” for an overview of the RMG sector’s contribution.

Macroeconomic indicators

Both the countries have grown at a healthy GDP rate of greater than 5% over the past 10 years. However, the GDP per capita of Vietnam (at USD 2,785) is about 50% more than that of Bangladesh (at USD 1,961). High population and low GDP per capita translate into more people living below the poverty line in Bangladesh. The poverty headcount ratio at USD 1.90 a day (2011 PPP) as a percentage of the population in Bangladesh is 14.5% compared to Vietnam, which is at 1.9% as per 2016 data. Over the past decade, poverty in Bangladesh has been relatively higher than that in Vietnam.

Both countries have a large population from the LMI category (83% in Vietnam and 61% in Bangladesh), earning about USD 2–10 per day. The public and private sectors understand the potential of this segment, which is evident from the success stories of the likes of bKash and MoMo.

Unemployment continues to persist in both countries. The unemployed labor force in Bangladesh is about twice that of Vietnam. As of 2019, Bangladesh’s unemployment rate was 4.19%, while Vietnam’s was 2.04%.

Here, the role of micro, small, and medium enterprises (MSMEs) is essential. Bangladesh has about 6.9 million micro-enterprises, while Vietnam has about 5.5 million micro-enterprises. These smaller enterprises are job-creating engines. They employ 1–3 people each in both countries, providing employment opportunities. When we focus on small and medium enterprises (SMEs), Bangladesh has 900,000 SMEs, which is considerably more than 124,680 SMEs in Vietnam. These SMEs are the backbone of the economies of Bangladesh and Vietnam.

Lately, innovation around serving these micro-enterprises has increased. Startups offer exciting solutions that benefit these micro-enterprises around credit, e-commerce, SaaS, book-keeping, skilling, providing market linkages, etc. These solutions are expected to increase the revenues of the micro-enterprises and help them create more jobs.

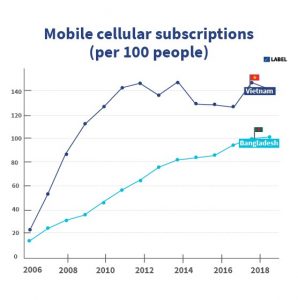

Digital financial services

Mobile phone ownership in both countries is relatively high—141 in Vietnam and 101 in Bangladesh (per 100 people). However, smartphone penetration (of 2020) in Vietnam at 63.1% is way ahead of Bangladesh at 32.4%.

As of 2020, the percentage of internet users in Vietnam (77.4%) is higher than in Bangladesh (70.5%). This internet penetration is equal or better compared to the world population (65.9%).

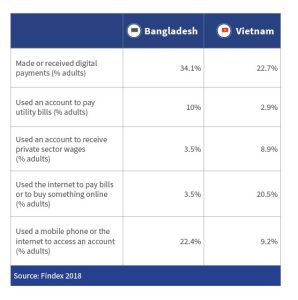

The table shows comparative data on digital payments in both countries. While Vietnam uses the internet for payments, P2P payments are most common in Bangladesh. In part because of a history of over-the-counter transactions, prominent players in Bangladesh, such as bKash, struggle to diversify from traditional use-cases of CICO (cash-in and cash-out) or P2P. In contrast, wallets such as MoMo have successfully convinced consumers to adopt more use-cases in Vietnam, though there is still scope to increase the volume, value and diverity of digital payments.

The governments of both countries continue to take the proactive steps, as so these Findex numbers are expected to rise in the coming years. For example, Bangladesh’s government has been working on transformational initiatives, such as the Parichoy e-KYC platform, BNDA interoperability project, and Startup Bangladesh. Vietnam’s government has set a goal to create firm foundations for a comprehensive digital transformation in 2021–2030. In June 2020, Vietnam approved the National Digital Transformation Program by 2025 to create a digital government, digital economy, and digital society while establishing competitive digital businesses globally. The Vietnamese government also approved a regulatory sandbox for FinTechs in September 2021 to foster innovation.

Both countries have been innovative in their drive for digital financial inclusion. But, as with most other countries around the world, they have a long journey ahead to make their LMI citizens financially healthy. However, with all these differences, the needs, aspirations and behavioral biases of LMI people are very similar in both countries.

Please tune in for our next blog, where we explain the key biases that complicate and facilitate the design of financial services in Bangladesh, in Vietnam and across the globe.

Credit for low- and moderate-income people in Bangladesh—can new-age banks and FinTechs deliver the regulator’s wish?

These days, “amake bKash kore dao” in Bangladeshi parlance means “send me money through bKash.” Mobile financial services (MFS) are so prevalent in Bangladesh that the market leader is synonymous with them. Despite the deep reach of MFS, World Bank data suggests access to accounts remains limited to just 50% of the population. However, access to formal credit is minimal: only 9.1% of the population have borrowed from the formal sector, as per the World Bank’s Global Findex database.

As the economy moves forward, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic, low- and moderate-income (LMI) people need credit to rebuild their lives and livelihoods. This need for credit has created a demand-supply gap since banks often fail to cater to the credit needs of the LMI segment due to four reasons:

- Lack of documentation—missing paperwork from the applicant and assets for collateral;

- Information asymmetry—difficulty in assessing credit applications due to limited publicly available information and digital footprint;

- LMI is viewed as a low-return segment—banks perceive the LMI segment as an unfavorable business case due to the nominal loan origination fees for small-value loans;

- Highly risk-averse nature of banks—that demand collateral to mitigate risk with little or no customization of the product.

Micro and small enterprises (MSEs) also struggle with a lack of access to credit for similar reasons. They need working capital credit to survive regular business volatility and increase their growth. Both LMI and MSE segments also require loans to withstand economic shocks in response to the pandemic. Digital solutions can emerge as frugal, disruptive, and effective solutions to address the demand-supply gap in credit requirement, given the difficulty of reaching the customers with these loan products.

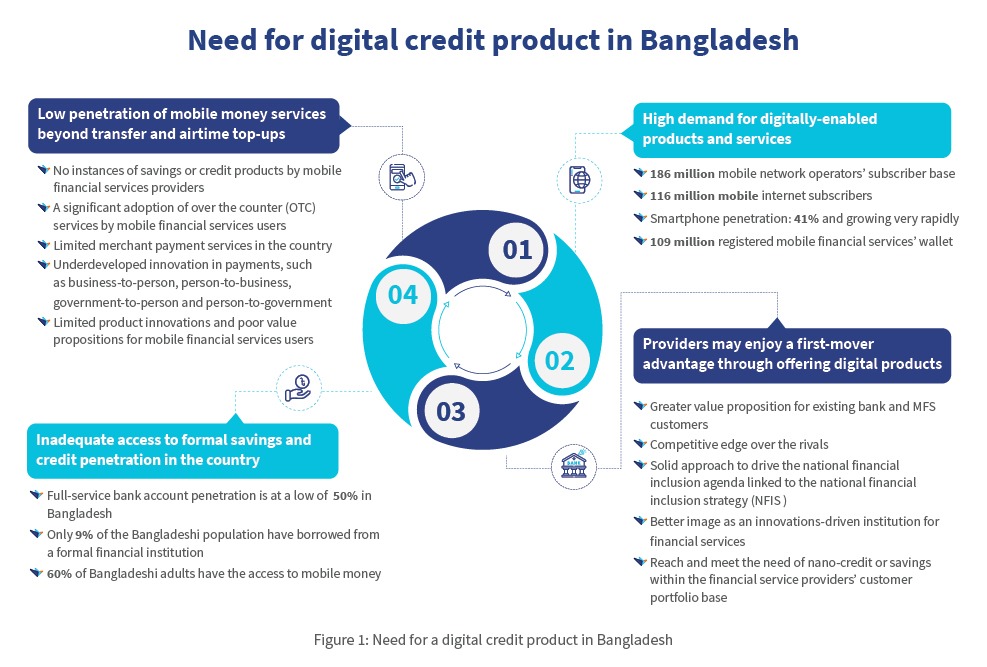

Bangladesh has a burgeoning digital landscape, but challenges remain

Bangladesh already has a high demand for digitally-enabled products and services. Data from the Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission (BRTC)suggests the country has 126 million active internet subscriptions, of which 92% are mobile-based. With growing internet penetration at 60%[1], Bangladeshis are more connected than ever. Approximately 60% of the adult population has active MFS accounts, with more than 1.1 million agents spread across the nation. However, despite this high penetration, MFS use-cases remain limited. As of 2021, 95% of all transaction value is basic cash-in, cash-out, or P2P payments. Only 5% are other use-cases such as utility bills, merchant payments, salary, and government disbursements.

While the unfulfilled need for credit among LMI remains high, banks and MFIs find it less cost-effective to reach the excluded segment. In contrast, 36.8% of people have borrowed money from other informal sources. These other sources can be family, acquaintances, informal lenders, or local samitis (cooperatives) that offer credit. In the absence of any verifiable record of these transactions, those borrowing in the informal sector cannot build a credit history to avail credit from formal financial sources in the future.

Digital credit in Bangladesh, multiple experiments, and an opportunity

As mentioned in the figure below, there are many reasons to explore digital credit in Bangladesh.

In response to this opportunity, a few players ran pilots in 2020. In July 2020, City Bank launched a “Nano Loan” product pilot, collaborating with the leading MFS provider, bKash. Upon completing the pilot, City Bank launched the product targeting LMI users who seek small consumer loans in December, 2021. The product is only available for bKash app users registered using eKYC. Similarly, Prime Bank introduced a nano loan product in 2021 for blue-collar workers. Both banks offered their products through mobile applications.

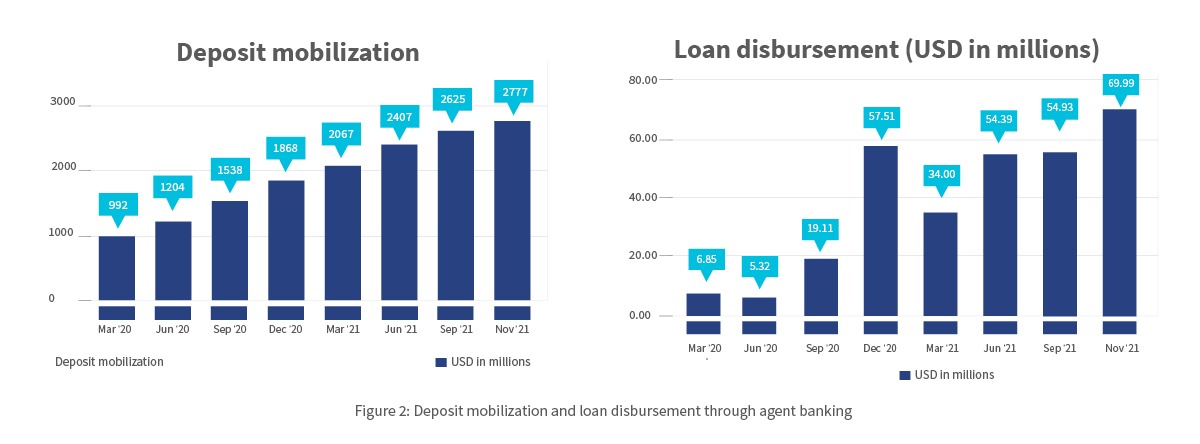

Besides the app-based lending channel, agent banking is another established avenue for providing credit to the underbanked segments, especially in rural and semi-urban areas. The rapidly emerging agent banking network provides robust distribution across the country. The agents themselves are capable advocates for financial products, including credit. The agent banking business collected deposits up to USD 2.59 billion across all accounts as of November, 2021, with a low credit-to-deposit ratio of only 2.52%. This shows an immense opportunity for future growth.

Do we have an enabling ecosystem?

Digital credit promises to deliver small-value credit at a lower cost.

Bangladesh Bank allowed banks to issue loans to the cottage, micro, small and medium enterprises (CMSMEs) under the government’s BDT-200-billion (USD 2.36 billion) stimulus package. This directive from the central bank highlights that 80% of the market consists of cottage, micro, and small enterprises, many of which need credit. The directive seeks to reduce banks’ risk of lending to CMSMEs as the government subsidizes 5% of the 9% interest rate.

Financial service providers have an opportunity to serve other LMI segments, such as students, readymade garment workers, and farmers. While Bangladesh Bank successfully launched eKYC guidelines for opening bank accounts, it is yet to make the loan application process easier. Earlier, MSC assessed the eKYC pilot in 2019 and highlighted opportunities to reduce the complexity of paper-based loan applications from 14-plus to two pages.

Furthermore, the digitalization of loan applications and assessment could significantly increase the probability of loan application approval among MSMEs. But concerns persist around accepting third-party data, proof of address, proof of identity, guarantor details, and nominees as part of the application process for digital borrowers. Bangladesh Bank’s forthcoming directive on digital credit operations may address these issues.

Digital onboarding, supported by eKYC and technologies, such as artificial intelligence and machine learning, could further simplify the loan application process and facilitate subsequent stages of loan operations.

Bangladesh Bank has also explored new channels to deliver financial services, such as neo banks. Bank Asia is one of the early adopters interested in forming a neo bank, the first in Bangladesh. In contrast to conventional banks that attach accounts to physical branches even if customers opt for internet banking, neo banks do not attach accounts to branches. When neo banking platforms gain momentum, they can potentially start offering small-ticket lending, such as retail and micro-credit, with minimal bureaucratic processes.

The road ahead

The market demand for credit remains high in Bangladesh. The country now has some of the building blocks to enable digital credit. However, any new product or platform requires careful regulatory assessment to protect consumers from potential predatory practices. The Bangladesh Bank will need to prioritize consumer protection and enable a responsible and responsive digital credit system. They must learn proactively from other markets like Kenya. Bangladesh Bank has already taken the first step by establishing the Regulatory FinTech Facilitation Office (RFFO) in 2019. The RFFO allows providers to test innovative ideas before they take them to the mass market.

The digitalization of credit should be a means to lower cost and make credit instant, automated, and remote. These three attributes differentiate digital from traditional credit, making it an easily scalable solution for LMIs and CMSMEs.

In Bangladesh, digital credit is no longer a question of “if” nor a question of “when.” Still, now more prominently than ever, it is a question of “how fast and how much” to suit the requirements of LMIs and CMSMEs.

Banks, NBFIs, FinTechs, MFS providers, MFIs, and development partners are all scrambling to forge partnerships and scope out opportunities to improve Bangladesh’s access to credit. MSC supports several leading banks, FinTechs, and development partners to usher in nano-credit. It will not be surprising if “nano” becomes the next buzzword from 2022, a decade after MFS became a household name.

[1] BTRC considers an internet subscription as active for customers who have accessed the internet at least once in the past 90 days. The mobile internet penetration covers all subscribers including multiple subscriptions.

“Train me like this”: Lessons from the pilot on IIBF BC/BF certification

“I scored 28 marks in my first attempt,” says Vikas Kumar, a 32-year-old business correspondent (BC) who finally cleared his Indian Institute of Banking & Finance’s Business Correspondents/ Facilitators (IIBF BC/BF) examination. This was his second attempt in the mandated certification examination to become a cash-in cash-out (CICO) agent. Vikas is among hundreds of other registered business correspondents who must qualify to operate as a CICO agent. However, he had to invest INR 1,200 (USD 16) to get through the examination—INR 800 (USD 10) for the first attempt and INR 400 (USD 5) for the second attempt.

The conundrum of IIBF BC/BF examination

In 2018, The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) authorized the Indian Institute of Banking & Finance (IIBF) to conduct the examination and certify CICO agents (see the rules and syllabus). The IIBF is a registered training body for the banking industry. The regulator introduced the certification to ensure that all BC agents had the basic knowledge of banking operations. The examination tests BC agents on topics, such as the basics of banking, types of interest rates, understanding of financial inclusion products—such as Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana, Pradhan Mantri Suraksha Bima Yojana, Pradhan Mantri Jeevan Jyoti Bima Yojana, Atal Pension Yojana, and complex concepts like cash flow.

Between 2012 and 2021, out of approximately 300,000 agents, who appeared for the IIBF BC/BF exam, only 62% passed the exam. Therefore, an estimated number of about 1.3–2 million agents lack the IIBF BC/BF certification[1]. The inability to clear the examination affects BC agents and Business Correspondent Network Managers (BCNMs). While the agents lose their livelihood, BCNMs or Banks lose active agents and spend additional resources recruiting and training new agents. Further, changing an agent reduces the trust locals have in the BC channel.

To overcome challenges in clearing the examination, MSC ran a pilot with the Centre for Development Orientation and Training (CDOT)—a BCNM that operates across eight states and 3,000 villages in India.

As most agent network managers in India have a dedicated team to train agents, we used the existing training structure at CDOT but modified the pedagogy and content. The interventions improved the conventional training method that handed over a guidebook or translated version of prescribed content to the BC agents earlier.

A design thinking approach to create an agent-centric solution

The MSC team observed that the current IIBF BC/BF module was complex for many potential agents. The technical terms and complex concepts often confuse the agents when they read the module. Further, they could not find answers to their questions in the module. For example, agents may know some commonly used English words like “fixed deposit” and “fund transfer,” but their Hindi translations are complex and archaic. In addition, from our interviews, we found out that most agents had never heard of concepts like “cash flow.” To tackle this, we divided the monolithic learning session into smaller, manageable modules and conducted counseling sessions for the agents.

The BCs were trained in smaller groups using a virtual classroom setup (Zoom/Google meet). The training was conducted in a counseling mode, and the content was shared upfront with the agents. The counselor (trainer) discussed the concepts and addressed questions in a session. The counselor encouraged the agents to discuss concepts and terminologies and highlighted the best approaches to attempt the exam and the commonly asked questions.

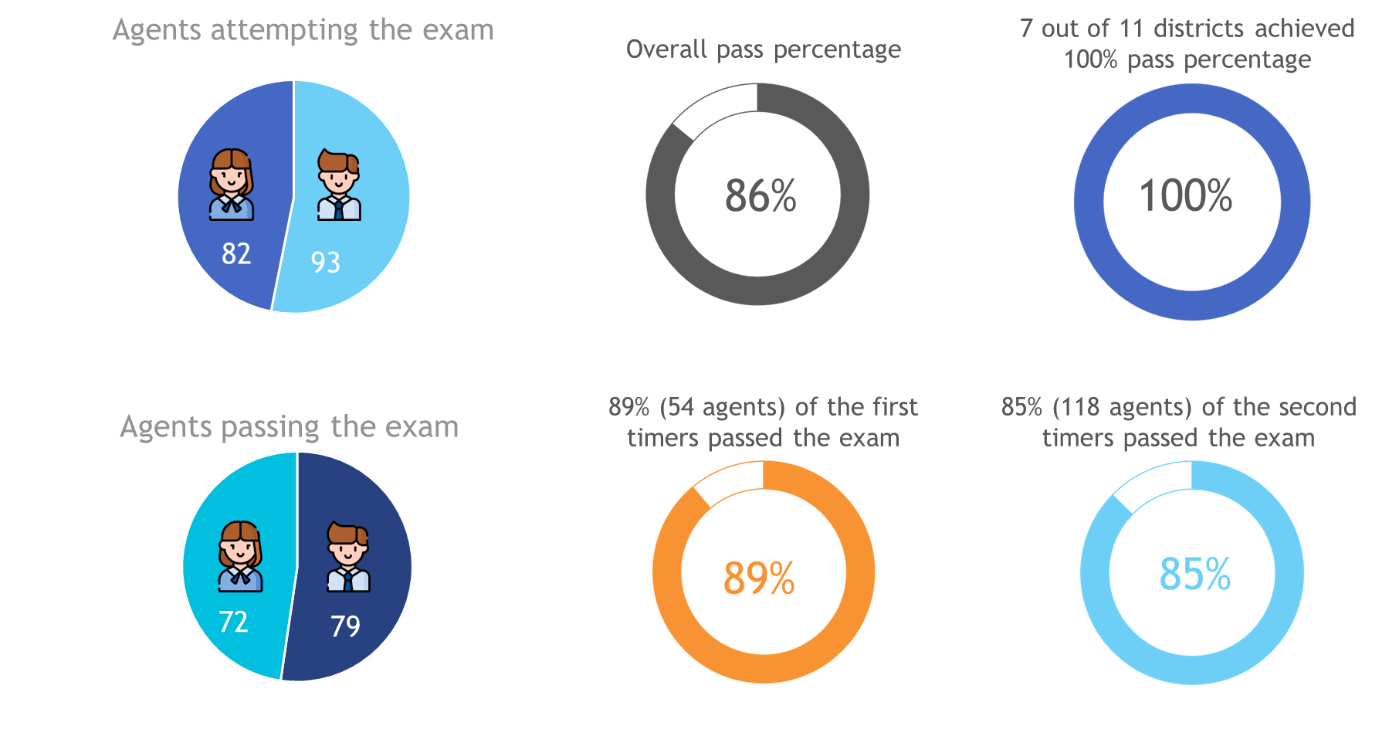

Enhancing agent certification rates by more than 43%

The immediate outcome of the overall intervention was encouraging.

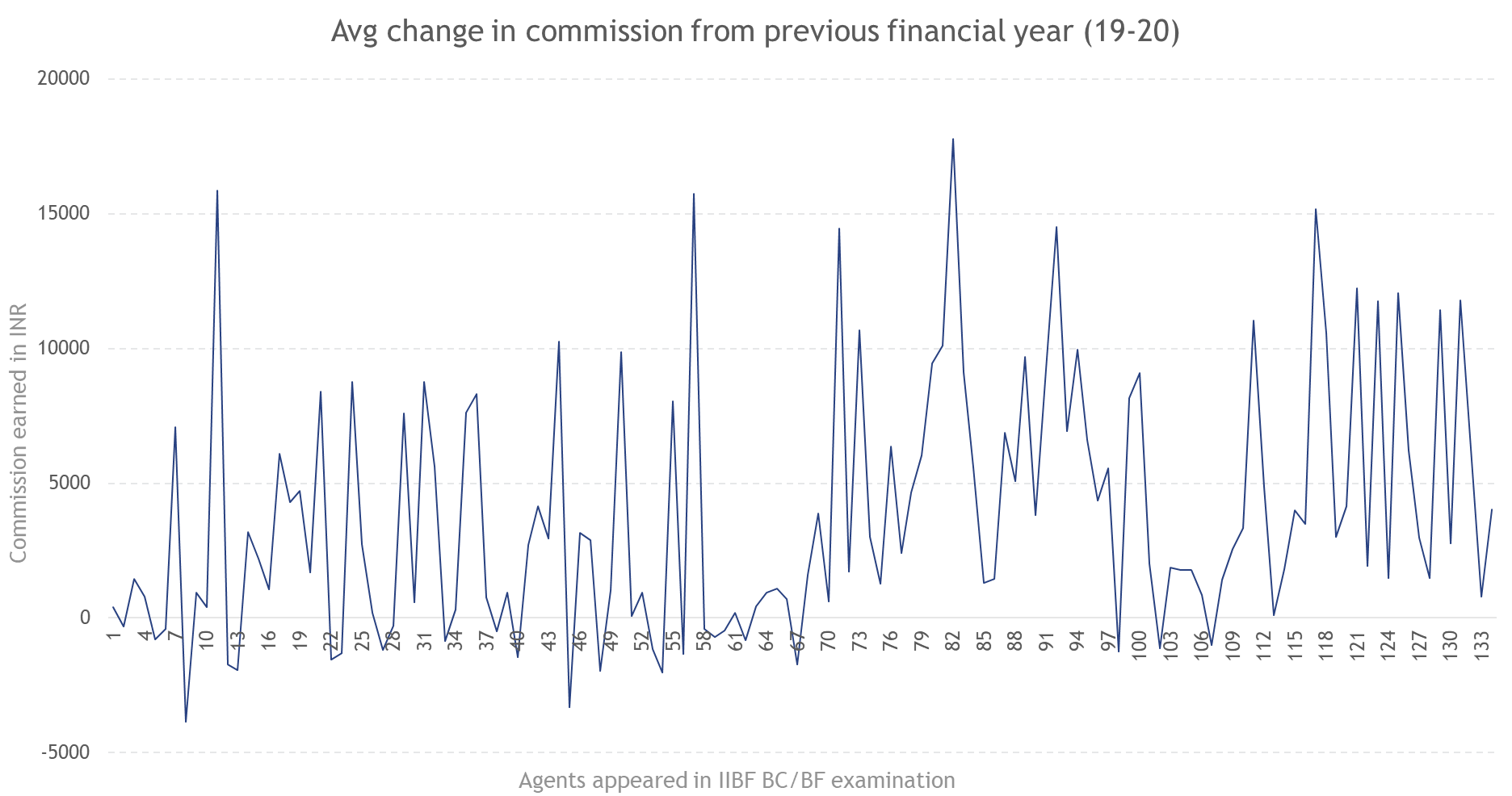

Interactions with the agents revealed that their confidence while dealing with customers increased. As found in our earlier work, a confident agent will likely attract more customers. The counseling-led training increased revenues for the agents.

Interactions with the agents revealed that their confidence while dealing with customers increased. As found in our earlier work, a confident agent will likely attract more customers. The counseling-led training increased revenues for the agents.

CDOT’s 175 agents appeared for the exam (see figure above). Of them, 151 (86%) passed the exam—a significantly higher number than earlier experience and comprehensive market data. The commission of certified agents also improved substantially.

In 2020, 128 agents saw an increase in revenue compared to 2019, with a median increase of INR 3,855 (USD 50)—150% from the previous year’s commission income. Of these, 110 (86%) had passed the exam. The remaining 18 agents, who failed the exam, only saw an increase of INR 2,014 (median increase of 67%).

In the few cases where agents’ income declined, the reduction in revenue over the past year was lower for the agents who passed the exam (median decrease of 27%, INR 1,330 (USD 17)) than for those who failed the exam (median reduction of 35%, INR 1917 (USD 25)).

“Earlier, I was afraid of cash handling matters. Now I can deal better with the customers as I am aware of products better. I provide services in the entire panchayat area.” (A CDOT agent in Bihar).

CICO agents in India have specific characteristics. These include their diversity (see figure below), the contexts in which they operate, the varied bouquet of services they offer, and the associated risks posed by the different technologies they use.

Figure 1: India has different archetypes of Business Correspondents (BCs)

Variations in these characteristics give rise to a persistent question — “Is the present system of certification through a single examination an appropriate long-term strategy for India?”

Variations in these characteristics give rise to a persistent question — “Is the present system of certification through a single examination an appropriate long-term strategy for India?”

With an overwhelming 90% of the existing BC ecosystem providing essential CICO services, policymakers may like to relook at the level of competency or the skill set required. One way to look at the solution is to have graded certification for different levels of BCs. The graded certification can vary by the type of services offered by BCs, as is available for payment banks (PBs) agents. The agents of PBs can pass the first module and start working as agents of PBs, while they offer restricted services. Then, the agents can graduate to the next level if they want to serve as agents for universal banks.

Finally, we believe that the providers must take a long-term strategic view to build their agents’ skills, considering adult learning principles and agent needs. CDOT’s pilot is an early indicator to adopt the counseling-led training model that increases agent income and reduces agent drop-out.

[1] As of December, 2020, the RBI provisional data suggests that there are 1.5 million agents countrywide. The industry estimates and some extrapolation based on NPCI unique device (AePS) activities suggest 2.3–2.4 million agents in India. Since 2012, 187,667 agents have passed the IIBF BC/BF examination. Hence, the number of agents without certification ranges from 1.3 million to 2.1 million.

Could 2022 be the watershed moment for the CICO networks in Indonesia?

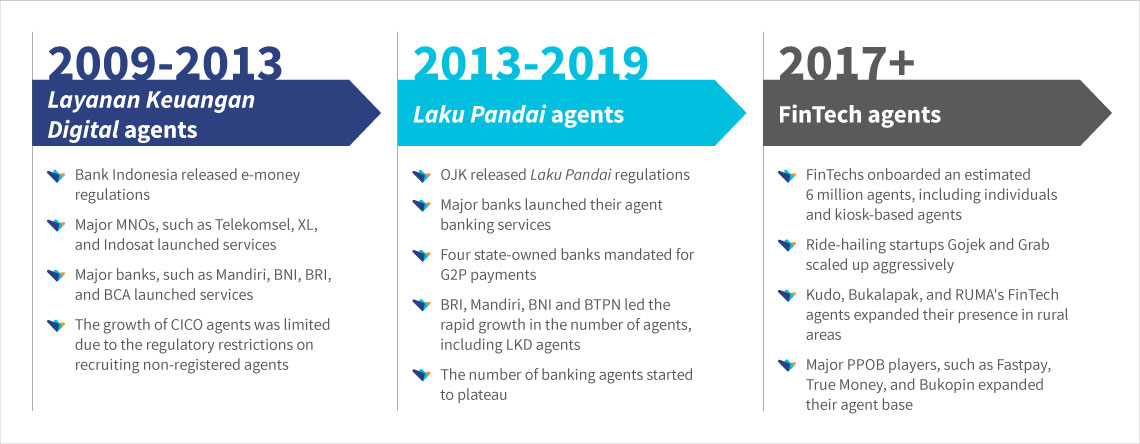

Cash-in and cash-out (CICO) networks are the backbones of any digital financial inclusion program. Despite having one of the largest unbanked populations in the ASEAN region, it was only in 2014 that the Indonesian policymakers passed regulations for branchless banking. The regulations gave impetus to the CICO networks as a last-mile delivery channel for financial access. The country has made remarkable progress on financial inclusion ever since. SNKI’s recent survey shows that financial account access increased from 24% (2015) to 62% (2020) over the past five years. This tremendous growth in financial account access is accompanied by an exponential growth in the CICO networks, both in numbers and services offered.

The graphic below outlines the evolution of CICO agent networks in Indonesia through the years:

Some estimates indicate more than 5 million CICO agents operate in Indonesia, including more than 2 million banking agents (OJK, 2021) and 3–4 million FinTech (non-banks) agents. However, the growth in the absolute number of CICO agents did not affect the quality of access provided through such networks. Further, while the number of CICO agents in Indonesia is considerably high for its size and population, MSC estimates that the actual number of active agents may be significantly less.

In 2017 and 2019, MSC assessed the health and sustainability of CICO networks in Indonesia, which highlighted low benchmark scores for crucial access, usage, and quality parameters. These issues were related mainly to the limited last-mile penetration of CICO networks, low volumes of transactions, and the overall sustainability of such networks as a complementary business line for an agent. The studies also showed that, except for one or two big players with deep branch networks, most service providers struggled to sustain the CICO network, particularly in remote rural locations.

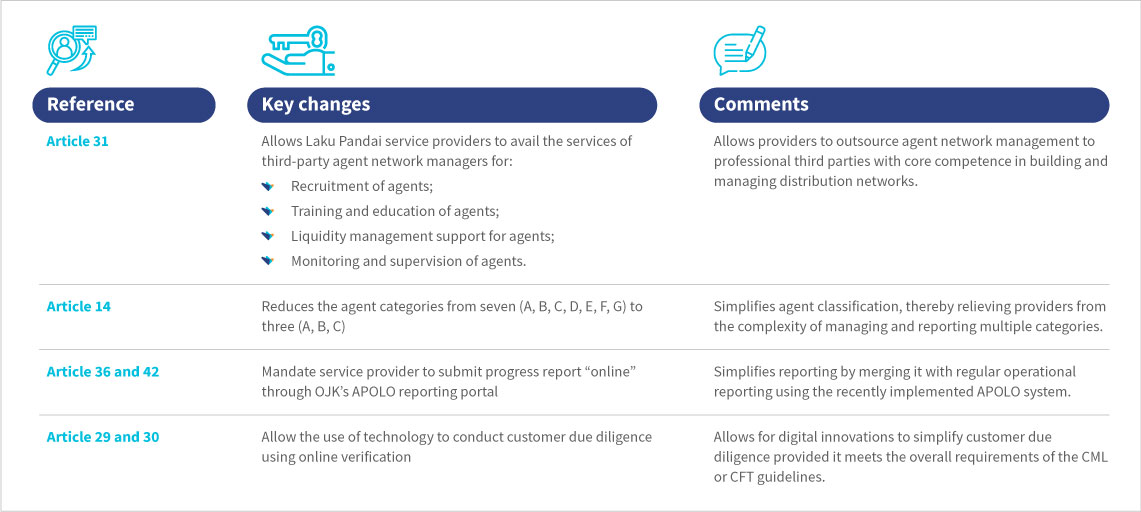

Backed by evidence-based insights, MSC highlighted some of the significant regulatory and policy roadblocks that prevented Indonesian CICO networks from achieving their full potential over the past five years. A critical regulatory issue that slowed the development of quality CICO networks was the lack of professional agent support services. Indonesia did not permit or encourage the concept of experienced third-party agent network managers. Third-party ANMs have been critical to the success of CICO network development in other more mature markets, such as India, Brazil, and Kenya. In January, 2022, OJK announced amendments in the branchless banking regulations. These changes address some of these issues and lay the foundation of an efficient and competitive CICO network infrastructure for the last mile.

The section below provides significant highlights of the new draft regulations:

Amendments in the draft regulations might appear incremental. Yet, the overall impact of these regulatory changes could be significant when combined with the changes announced by Bank Indonesia for the operations of payment service providers (Bank Indonesia Nomor 23/6/PBI/2021).

MSC published a paper in 2018 on “Aligning regulations to enhance digital financial inclusion in Indonesia.” We highlighted aspects of e-money and branchless banking regulations that required harmonization to reduce entry barriers and create a more level playing field for the service providers engaged in CICO network infrastructure. Bank Indonesia’s latest regulations address some of these concerns by allowing banks or non-banks to recruit individual agents (Article 172) and allowing service providers to collaborate with third parties for agent network management (Article 175).

We expect the recently announced amendments in the regulations to transform the CICO networks in Indonesia. In particular, we anticipate the following critical implications:

Deepening of CICO networks: MSC’s research highlights that in Indonesia, around 85% of bank agents for most service providers operate within a 15-minute distance from a bank branch. Therefore, despite the significant number of CICO agents, many households in remote rural areas lack convenient access to CICO services. The new regulations reduce the entry barrier for service providers to expand their CICO network into remote areas. They can now partner with professional agencies that have the capability and competence to build and manage distribution networks. This model has worked remarkably well in other more mature CICO markets like India, Bangladesh, and Kenya.

Increased competition and consolidation: One or two big players dominate the CICO landscape in Indonesia. Despite the challenging business case, these players either have a brick-and-mortar presence through their existing branch networks in rural areas or have deep pockets to sustain their networks. However, many FinTech players operate on the PPOB (payment point online bank) model and provide a limited set of over-the-counter (OTC) services, primarily top-ups and bill payments. These players may merge or collaborate with large incumbents to sustain such high-volume, low-margin businesses. The new regulations may also increase the choice for customers to access alternative channels for CICO, including a more comprehensive bouquet of digital financial services through non-bank or FinTech agents.

Improvement and innovations in agent management practices: With a booming FinTech ecosystem, Indonesia may also witness the emergence of new FinTech solutions that redefine the existing agent network management practices, including recruitment, training, liquidity management, monitoring, and supervision, and make them more efficient. Given concerns around sustainability, most service providers have not invested adequately in technology-enabled agent network management solutions. Further, due to the regulatory uncertainty, many FinTechs shied away from building agent network management as a standalone business line. MSC highlighted the type of changes that may emerge in a recent report for GSMA, including the use of big data and advanced analytics to monitor agents and track or predict their liquidity positions.

The significant role of agents in customer acquisition: MSC’s ANA research highlighted that only 28% of CICO agents offered account-opening services. This means that most customers transacting at CICO agents were the bank’s existing customers. The Laku Pandai program added only a few new customers. However, the revised regulations may encourage CICO providers to design an efficient digital process that allows customer acquisition for savings accounts and credit. MSC’s research on KYC practices in Indonesia shows that providers can reduce customer acquisition costs significantly through digital identity solutions. However, its success will depend on an enabling digital identity infrastructure provided by the Government of Indonesia.

While the new regulations ease some of the supply-side pain points, the success of CICO networks will continue to depend primarily on critical demand-side issues, such as building appropriate use-cases that drive transaction volumes at the CICO agent point. Meanwhile, questions persist, such as—how will the commercial engagement models between the incumbents and third parties pan out?

The existing regulations maintain the earlier stance of not allowing service providers to price their CICO services over and above the regular transaction pricing in traditional delivery models. Yet, the concerns around sustainability in the existing business delivery model could limit service providers’ ability to adequately reimburse the third parties for their services.

Overall, the new policy direction for the CICO networks looks promising on paper. However, we are yet to see how the industry embraces these recent changes. Are the service providers already fatigued due to sustainability concerns, or do they see the proposed draft amendments as an opportunity to reassess and reframe their CICO strategy?

Impact of COVID-19 on FinTechs: India

MSC conducted a three-phase study to analyze the impact of COVID-19 on the Indian FinTech ecosystem. Our first report assessed the impact of the pandemic and the strategies of FinTechs to adapt to changing market conditions. In contrast, our second report shed light on how the FinTech ecosystem has progressed and adapted to the new normal. Our third and final report comprehensively assessed investor sentiments, policy response, and customer behavior in 2021. It looked into the strategies of FinTechs and developments in the ecosystem to bolster business growth over the second wave of COVID-19.