Investing with heart and wisdom: Strategic amplification of female agency frontlines

by Brenda Oyugi, Shweta Menon, Mitali, Gayatri Pandey, Raunak Kapoor, Akhand Tiwari and Edward Obiko

by Brenda Oyugi, Shweta Menon, Mitali, Gayatri Pandey, Raunak Kapoor, Akhand Tiwari and Edward Obiko Mar 18, 2025

Mar 18, 2025 6 min

6 min

MSC undertook research on female agents with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (BMGF) to identify factors that can overcome the barriers impeding the recruitment and sustainability of female DFS agents. This blog highlights key insights from the study. The detailed report can be accessed here.

The stories of female financial agents are strikingly similar worldwide, no matter where they operate or their business lifecycle. Regardless of their specific contexts, female agents work under far-from-ideal conditions. Unlike their male counterparts, they often grapple with inadequate support, pervasive social barriers, and scarce resources imperative to sustaining and growing their businesses.

In Nigeria, while female agents are more visibly engaged in agency banking, they face significant hurdles, particularly in maintaining sufficient cash flow. A weekly cap on bank withdrawals worsens their challenges—a common issue in other countries—which forces these female agents to rely on loans to run their businesses and manage liquidity. This reliance on borrowed funds adds another layer of complexity to their already challenging roles.

In India, female agents have limited customer outreach and may not get support like male agents and BC Sakhis (a type of female agent supported by the government). Meanwhile, in Uganda, female agents face cultural expectations that confine them to domestic roles, which limit their time and mobility to manage their businesses effectively.

A gender-balanced network of DFS agents helps bridge the gap between underserved populations and formal financial systems to accelerate financial inclusion. Female agents play a unique role in fostering trust and accessibility, especially among female customers who may feel more comfortable interacting with someone of the same gender. This comfort can break down social and cultural barriers that often prevent women from accessing financial services.

While policy focus on female agents remains limited globally, notable exceptions exist in countries such as India, Pakistan, and Nigeria, which have introduced targeted initiatives. However, these efforts are far from comprehensive, and the broader ecosystem worldwide continues to present significant hurdles for female agents.

What can amplify female agents’ numbers and performance?

Our research found that providers may lack a fair understanding of the business case for female agents, which results in a limited focus on women’s recruitment and retention. A lack of gender-disaggregated data worsens this situation.

Many markets, such as Uganda, Kenya, and Ethiopia, lack the mandate to collect gender-disaggregated agent data. This prevents providers from understanding the differences between male and female agents and makes the creation of targeted policies and support mechanisms difficult. Providers do not prioritize gender-disaggregated data collection, often due to a perception that female agents offer limited business value. This oversight strengthens barriers to female agents’ recruitment, retention, and overall success.

Even where gender-disaggregated data is collected, it is often underutilized, which prevents providers from assessing differences in the unit economics of female and male agents. This issue is prevalent in both developed and emerging markets.

We analyzed gender-disaggregated data from a few providers who record gender disaggregation. It revealed that female agents are more likely to serve vulnerable groups, such as women, customers with disabilities, and elderly customers. We also identified methods to tap into networks for recruitment.

In East Africa, although women manage their liquidity needs as well as men, if not better, they have less working capital. Women report holding 10-30% less cash and e-float than men across three East African markets. In Uganda, some female agents borrow from their village savings and loan associations (VSLAs) and savings and credit cooperative organizations (SACCOs), while others, especially in rural areas, buy float from super agents, which carry premiums compared to borrowing directly from providers.

Lending to agents is primarily driven by the private sector and often lacks customization for female agents, who frequently struggle to repay loans within short timeframes. This difficulty arises from barriers, such as high upfront business costs, often higher for women. The high costs, in turn, stem from factors such as limited access to affordable startup capital, expenses to secure accessible and safe business locations, and funds needed to set up and maintain the agency infrastructure.

Additionally, women often face higher transaction costs due to mobility constraints and the need for additional security measures to ensure their safety while they operate their businesses. Household responsibilities and other social norms further exacerbate these challenges. However, the most significant challenge is their lower income and savings, which makes them economically vulnerable and potentially risky for lenders. As a result, female agents face unique viability concerns that impact their sustainable participation in the digital financial services ecosystem.

While all agents grapple with viability, gender-specific products at CICO locations have been shown to enhance women’s financial inclusion and female agents’ income. However, many FSPs lack products tailored specifically for female clients that female agents can promote and deliver.

Female agents in countries such as India are often the last to receive training on non-CICO products, such as credit lead generation, which could significantly enhance their business viability. This lack of targeted service offerings and training limits female agents’ ability to utilize their market presence fully and meet client needs. Similarly, female agents in Bangladesh frequently struggle during recruitment due to cultural norms and safety concerns, which discourage their participation in agent networks and lead to a gender imbalance. Moreover, female agents in Nigeria face higher dropout rates due to a lack of mentorship programs and inadequate support systems that fail to address their unique challenges, such as balancing work with domestic responsibilities. These gaps in recruitment and retention strategies hinder female agents’ growth and sustainability across these regions.

All these challenges are compounded by deeply rooted social norms that often discourage women from taking on roles perceived as unconventional, such as managing a financial outlet. Policymakers and service providers have long struggled to recruit female DFS agents, retain them, and address the barriers that limit their participation and success.

The heart and the wisdom

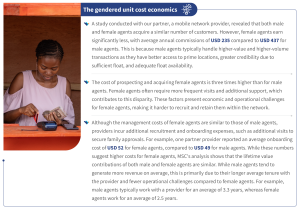

A significant challenge in recruiting and retaining female DFS agents is the lack of a clear and well-understood business case for their inclusion. Female agents earn less than their male counterparts, even when they enroll more customers.

However, the current economics also do not show a clear picture, as they fail to account for many nuances, such as the Lifetime Value (LTV) of agents. Various stakeholders we spoke to indicated a lack of understanding of the LTV of agents disaggregated by gender. For example, they overlook that female agents often provide superior customer service, a valuable asset for FSPs, and they recruit more customers (including female customers) who, in turn, bring business over the years.

If these female entrepreneurs are provided adequate support—which we know is often lacking—they are likely to perform better. If FSPs are to address these disparities, they must develop business models that acknowledge the lifetime value of female agents in terms of their role in maintaining a consistent and inclusive business and driving revenues for the provider, even if they earn less. By valuing these contributions, the financial sector can create a more inclusive environment that supports female agents’ growth and success. If the sector can focus on the unique challenges of female agents, they will go beyond merely participating in the ongoing evolution of CICO agent networks—to lead it.

The strategic amplification of female agency frontlines in digital financial services is not just a matter of gender equity. It is a critical component in expanding financial inclusion. As the stories of Amina and many other women across diverse regions illustrate, female agents face unique challenges that require targeted interventions and support. Addressing these barriers—whether related to social norms, access to capital, training, or mobility—is essential for unlocking female agent networks’ full potential.

[1] The figures mentioned here correspond only to this mobile network provider interviewed as part of this study. The provider here is an established market player with a huge network, and hence, these figures may vary for other providers depending on their size and other parameters.

Written by

Brenda Oyugi

Manager

Shweta Menon

Senior Manager

Mitali

Assistant Manager

Gayatri Pandey

Assistant Manager

Raunak Kapoor

Associate Partner

Leave comments