As Indonesia continues to build its economic growth based on the foundation of its rich natural resources, a critical opportunity lurks within its waters in the form of fish and other aquatic foods. Often called “blue foods,” fish and aquatic foods are a dietary staple for millions across the archipelago. Fish plays an essential role in meeting the nutritional needs of Indonesians. Between 2017 and 2022, the country’s per capita fish consumption has climbed steadily from 47.34 kilograms to 57.27 kilograms, as per December 2023 data from Statistik Kementerian Kelautan dan Perikanan. This rise signals the increasing role of fish in the Indonesian diet. Yet despite this growth, malnutrition, particularly among children, persists alongside widespread micronutrient deficiencies.

This paradox—high fish consumption alongside malnutrition—points to significant gaps in dietary intake and highlights the urgent need for policies that promote nutrition-focused blue food systems. Take East Nusa Tenggara as an example. The province faces the highest case of stunting in Indonesia at 37.9%, way above the national average of 21.5%, despite a per-capita fish consumption of 53.06 kg, only slightly below the national average.

To understand the paradox, we must dive into the heart of the fish supply chain, which comprises the country’s small-scale fishers. More than 10 million people are involved in small-scale fisheries in Indonesia, around 5 million of whom engage in fishing mainly to feed their households. For these communities, fish serves as a source of sustenance and income, which leads to trade-offs that can limit the nutritional benefits they derive from their daily catch.

Research from MSC Indonesia and Bappenas reveals that many fishers struggle to consume nutritious seafood themselves despite their vital role in the fish supply chain. While fish is a staple in their diets, fishers often sell high-quality fish to earn a living and consume lower-value fish at home. During lean seasons, this challenge intensifies and forces many to turn to less nutritious options, such as instant noodles. When fishing yields are low, fishers often buy cheaper, lower-quality fish from local markets. Price, rather than nutritional value, drives fish selection in these households. This behavior reflects broader economic hardships and limited nutritional literacy in low-income coastal communities.

Fishers also widely practice traditional preservation methods, such as salting and drying, to ensure food security during off-seasons. However, these methods can reduce the nutritional value of the fish. Consequently, many fisher households rely on simple meals of fish, rice, and sambal (chili paste) with minimal use of vegetables or nutrient-dense foods. Although fish remains a dietary mainstay, the unchanging preparation and preservation techniques limit their intake of essential fatty acids, vitamins, and other vital nutrients. For young children and new mothers, the lack of dietary diversity hampers ability to achieve optimal nutrition, particularly in the crucial first 1,000 days of life, and contributes to stunting and other malnutrition linked growth and development delays.

The lack of nutritional knowledge also affects dietary choices among pregnant and lactating women, who can benefit greatly from nutrient-rich seafood if they are empowered to make informed dietary choices. Limited knowledge, access or affordability of their specific dietary needs can leave vulnerable populations, including children, women, and the elderly, with nutritionally inadequate diets.

The current state of nutrition and dietary practices among fishers highlights a critical opportunity: Around 69% of Indonesia’s poor population lives in coastal areas, where many engage in fishing. Enhancing fishers’ access to nutritious blue foods could significantly benefit their health and well-being alongside that of the broader low-income coastal communities they represent.

Indonesia’s blue food economy has a unique opportunity to catalyze improved nutrition outcomes nationwide. Realizing this potential requires a holistic approach that enhances awareness, affordability, and accessibility and integrates blue foods into existing systems and practices.

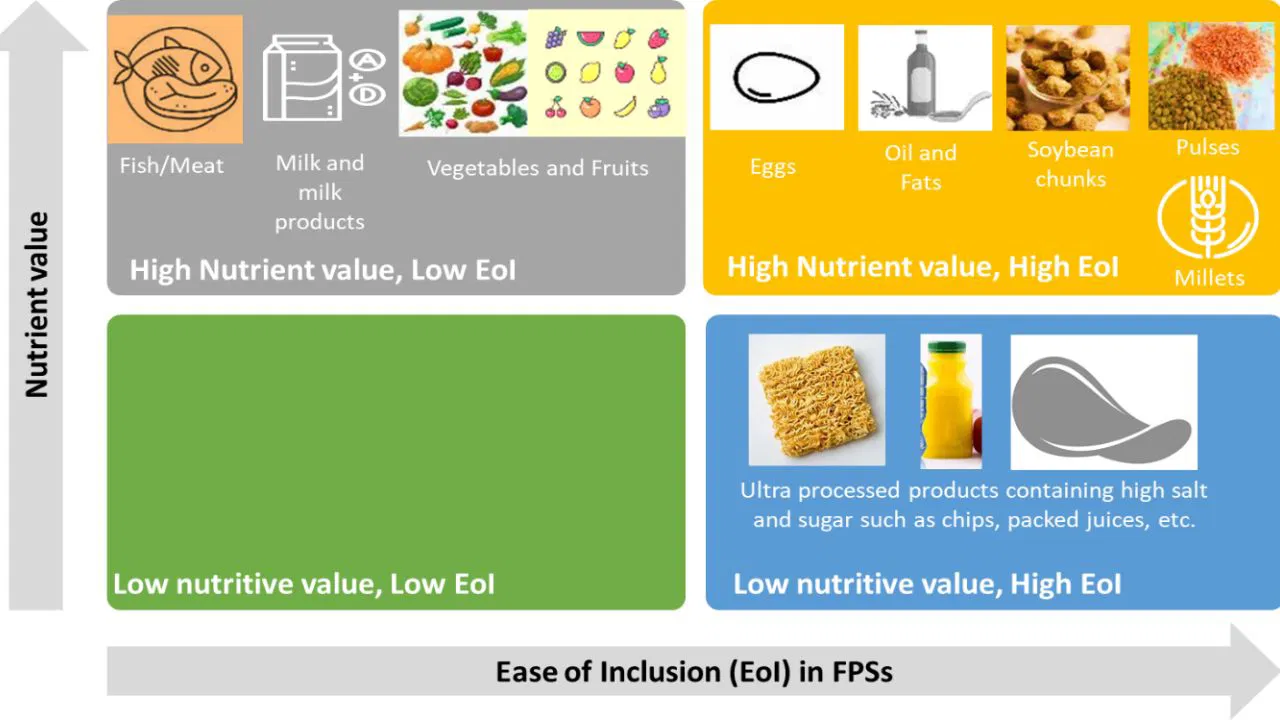

First, the government and private sector should collaborate to improve the affordability and availability of nutrient-dense fish. Strategies, such as subsidies for farming high-value species, along with community-driven fisheries that prioritize local consumption can broaden access to these resources. In underserved areas, as demonstrated in India, initiatives to increase the availability of nutrient-rich fish can diversify diets and reduce the dependence on less nutritious alternatives.

One transformative approach lies in the incorporation of blue foods into national nutrition and social protection programs. Examples from other regions, such as the Philippines, show that integrating fish into social safety nets can yield significant health benefits. In Indonesia, integrating blue foods into social assistance initiatives, such as the Bantuan Pangan Non Tunai (BPNT) program, could help achieve this goal by providing essential foods to vulnerable families. The expansion of these programs in coastal areas would ensure that more nutritious seafood reaches households in need.

Likewise, promoting fish-based options for pregnant and breastfeeding women through the Program Keluarga Harapan (PKH) can help enhance the nutritional outcomes for vulnerable populations. Moreover, the anticipated launch of a national school meal program offers a valuable opportunity to incorporate fish-based meals in schools, especially in regions with high blue food production. This inclusion would enhance children’s nutrition and develop healthy eating habits early on.

Another crucial step is increasing nutrition literacy among fisher communities. Despite fish being a staple in their diet, many remain unaware of its specific health benefits, such as the role of omega-3 fatty acids, essential vitamins, and minerals in maintaining overall well-being. Community-based education programs delivered through local health clinics, schools, and fishing cooperatives can help these communities better understand the nutritional value of various fish species and the importance of nutrient-preserving preparation methods. Tailored information, education, and communication (IEC) materials, cooking demonstrations, and the training of community health workers can empower households to make healthier food choices. These initiatives can highlight the value of a balanced diet to help maximize the intake of essential macro and micronutrients.

Fostering dietary diversity through cultural and behavioral changes is equally important to complement education. Social and behavior change communication (SBCC) campaigns can encourage healthier cooking methods and promote the inclusion of locally available fruits and vegetables alongside fish. Moreover, Indonesia’s vibrant cultural festivals that celebrate fisheries—such as those featuring crabs or grouper—offer unique opportunities to engage communities. Nutrition experts can use these events to promote health literacy through recipe competitions, cooking demonstrations, and interactive sessions that underscore the importance of diverse and balanced diets.

The Indonesian government has already shown a strong commitment to advance blue foods and improve nutrition outcomes. Indonesia can unlock the full potential of its blue food economy if it combines education, economic support, and cultural engagement with strategic program integration. By doing so, the nation will be able to nourish its people and set a global example of how aquatic resources can drive sustainable and equitable health outcomes.

This article was first published in The Jakarta Post on 27th November 2024.