This report delves into indigenous financial services (IFS) in Kenya, Ghana, and Togo. It highlights the pivotal role IFS play to advance financial inclusion for micro and small enterprises (MSEs). It emphasizes the distinct advantages IFS offers, such as enhanced accessibility, reduced costs, and fewer entry barriers compared to formal financial sectors.

Blog

Digital gender equality strives to connect half the world to the internet

Women-led development is one of the core focus areas of India’s G20 presidency. Since 2015, G20 has improved its focus on prioritizing and mainstreaming gender equality. The G20 Bali leader’s declaration mentions women ‘17’ times and ‘digital’ 33 times. It commits to putting gender equality at the core of G20 efforts for sustainable development.

Digital gender equality can be achieved when women benefit equally from the possibilities and potential of the internet. India has put in place the building blocks to achieve this by creating a robust digital public infrastructure (DPI). DPI created the foundation for open networks in MSME credit, universal health coverage, and e-commerce.

More than 50% of women in the workforce are self-employed. E-commerce lowers barriers to entry for these entrepreneurs and enables greater market access. However, small sellers, the majority of whom are women-led businesses, find it hard to pay the heavy platform commissions and typically earn less on platforms. Finding ways to include them will not only lead to greater equality but will also boost the GDP. India’s ONDC may bring this about by disrupting the e-commerce space to create a level playing field for smaller sellers. Onboarding more women sellers online and closing the gender gap in earnings on e-commerce platforms has multiple benefits. It brings more women sellers online, provides greater access to markets, and increases sales, incentivizing the entry of more women entrepreneurs.

Similarly, the Women’s Entrepreneurship Platform (WEP) of Niti Aayog is another example of a DPG addressing information and networking needs of women entrepreneurs.

Government eMarketplace (GeM) which facilitates public procurement of goods and services for government entities, has set a target of 3% procurement from women entrepreneurs. Reportedly, 1.44 lakh micro, small women enterprises have fulfilled orders worth Rs 21,265 crore in gross merchandise value (GMV).

In a world where access to resources is increasingly mediated by technology, inclusive digital Innovation has a key role to play. When deliberately designed to be equitable, innovation creates a vital pathway for gender equality. Focus on gender-inclusive digital innovation becomes even more critical in the face of the enormous gender digital divide.

There is ample evidence that a widening gender digital divide risks women being left behind. Over 30 years after the internet was born, one-third of the world’s population remains offline. Many among the online population, especially women and girls, are not “meaningfully connected” because of a lack of access to devices or connectivity that is unreliable, slow, or costly connectivity; or lack of digital skills needed to get the most out of devices and services.

The digital gender gap is also costly. Estimates suggest that countries have missed out on USD 1 trillion in GDP due to women’s exclusion from the digital world.

One lesson the previous industrial revolutions can teach us about the 4th Industrial Revolution is that if old jobs are destroyed, new jobs are created where there are capital and innovation capabilities. The emerging economies of G20 have demonstrated the latter significantly. India’s DPI starting to facilitate women entrepreneurs through various digital public goods like ONDC and GeM is the best example of this.

As India convenes the third G20 Ministerial Conference on Women’s Empowerment this year, it’s time to show what global solidarity could do to close the gender digital divide. Only bold commitments translated into concrete actions will ensure that half of the G20 population is not left behind in the rapidly digitalizing global economy.

The article was first published in The Economic Times on 30th April 2023.

Digital transformation strategies in Ugandan banking

MicroSave Consulting (MSC) is a boutique consulting firm that has, for 25 years, pushed the world towards meaningful financial, social, and economic inclusion. These podcast series are hosted by MSC for dedicated founders, start-ups, investors, and other stakeholders in the startup ecosystem. Through this bouquet of curated conversations around developments in the financial inclusion space, we offer insights and lessons based on our research and expertise.

This podcast delves into the strategies banks have been implementing to drive digital transformation to enhance the customer experience in Uganda.

Bridging the digital divide: Strategies to enhance women’s entrepreneurial success in home-based enterprises

MicroSave Consulting (MSC) is a boutique consulting firm that has, for 25 years, pushed the world towards meaningful financial, social, and economic inclusion. These podcast series are hosted by MSC for dedicated founders, start-ups, investors, and other stakeholders in the startup ecosystem. Through this bouquet of curated conversations around developments in the financial inclusion space, we offer insights and lessons based on our research and expertise.

In this podcast, Brenda Oyugi and Pauline Katunyo of MSC speak about the digital challenges women entrepreneurs face and solutions that empower them.

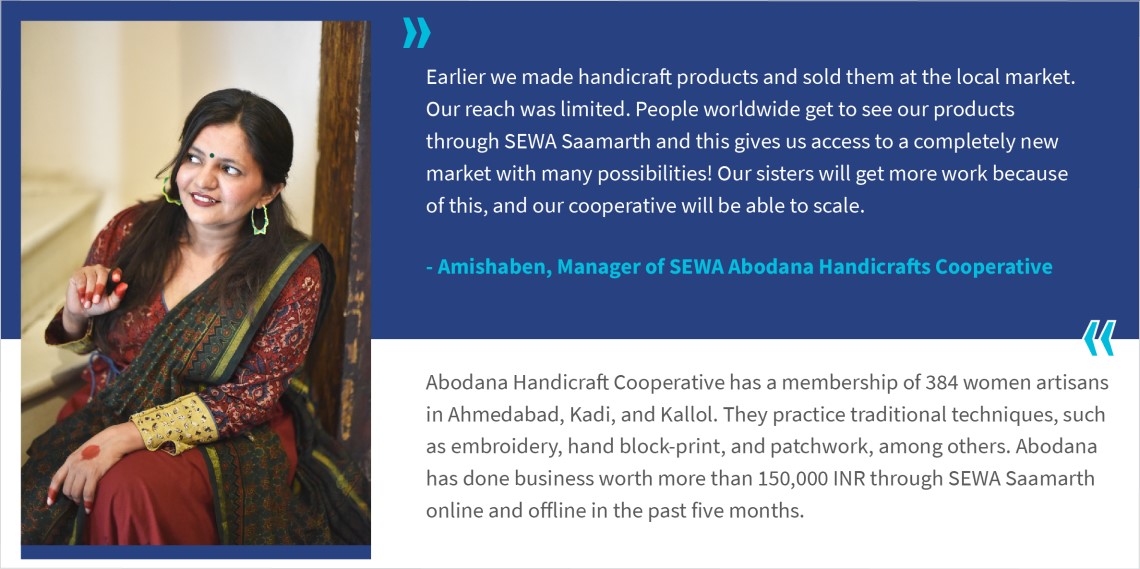

Strengthening market linkage through digital innovation and community support: SEWA Saamarth’s entry into e-commerce.

More than 91% of women in India’s labor force work exclusively in the informal economy. They lack access to regular work, steady income, social security benefits, and bargaining power. Women manufacturers and artisans must deal with intermediaries to ensure their products reach end consumers. These intermediaries often charge high commissions and prevent these women enterprises from being able to access suppliers, retailers, and networks of other producers in the industry transparently. This hinders their ability to build their skills and expertise.

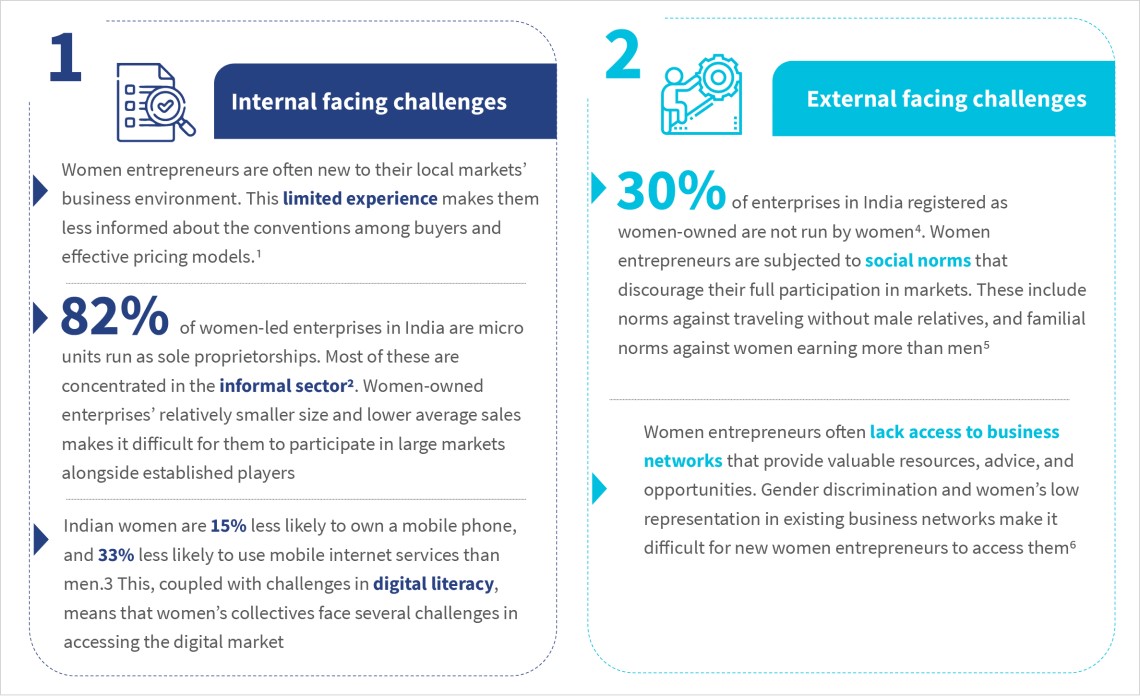

Access to markets is critical to ensure small and growing businesses meet the customer demand for their goods and services effectively. However, India’s 13.5 million women-led enterprises face unique challenges in access to markets. We have outlined a few such challenges below:

Sources: 1. The World Bank, 2,4. NITI Aayog, 3. Oxfam, 5. World Economic Forum, 6. Brookings

Figure 1: Challenges women-led enterprises face

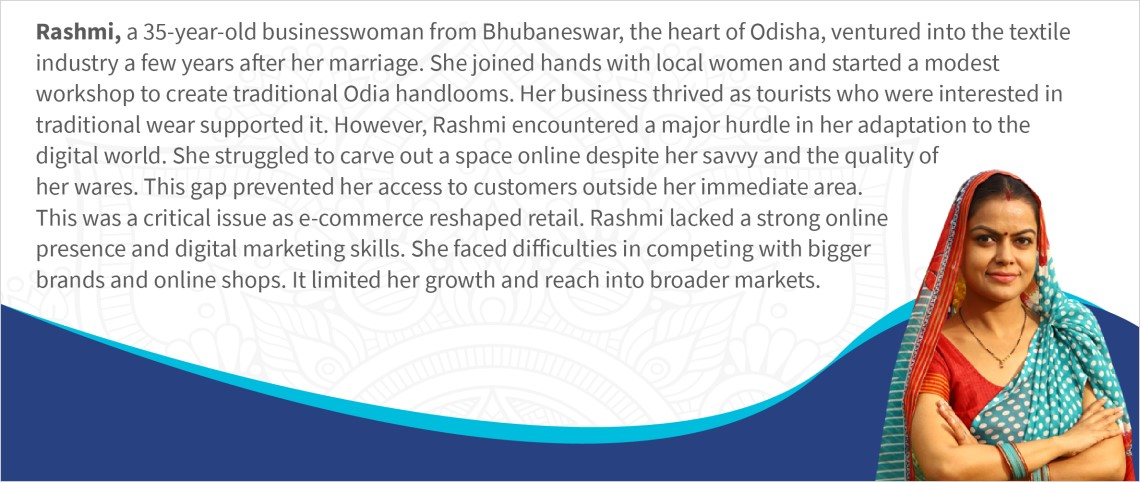

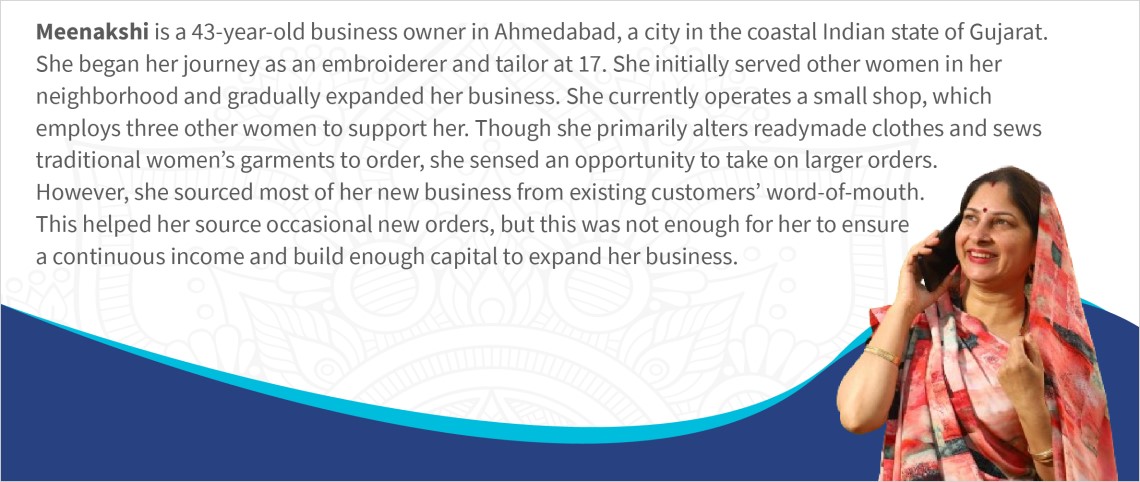

Women-led businesses (WLBs) across different sectors and geographies experience these challenges. We have outlined a few such examples from MSC’s extensive work in this space below:

Figure 2: Case study: Challenges in access to the market

Many WLBs in India struggle to identify buyers, adapt to new markets, and expand their businesses. Digital solutions can act as a catalyst to enable women entrepreneurs and women’s collective enterprises to get a head start in access to local markets, communicate with suppliers and service providers, and connect their products and services with potential buyers. Information and communication technology (ICT) can also facilitate new networks of women’s collective enterprises nationwide. This can help women support each other through shared advice, opportunities, and business development strategies.

Many programs have adopted ICT-driven solutions to bridge the global south’s market access gap for women’s collective enterprises. We supported our partner, the SEWA Cooperative Federation, in our women-led business program, funded by the MetLife Foundation. We supported their women’s cooperatives and collective enterprises through the development of a platform that they could use to gain wider market access.

SEWA Cooperative Federation initially supported its collectives to sell their products on existing private and government-supported e-commerce platforms. However, the collectives faced challenges, such as lack of discovery, high cost of marketing, long turnaround time to fulfill orders for handmade products, complicated backend systems, need for laborious documentation, and high commissions.

The Federation learned from this setback and built their proprietary e-commerce platform, SEWA Saamarth, to bridge the gap between women’s collective enterprises and the digital market. This platform seeks to solve the challenges that women’s collectives face in India.

The SEWA Cooperative Federation and SEWA Saamarth

The SEWA Cooperative Federation works with women’s cooperatives in six sectors and promotes women’s economic empowerment and independence through collective businesses’ owned, managed and run by women. Its main goal is to offer a consistent support system for these enterprises, within the country and globally, to ensure their sustainability in finance and decision-making. The Federation supports more than 100 cooperatives owned and led by women in six key areas—agriculture, dairy, crafts, services, savings and credit, and labor. It seeks to achieve full employment and self-sufficiency for women in informal sectors. Additionally, it serves as a crucial network that enables cooperatives to help each other create value chains, market and sell their products and access financial services.

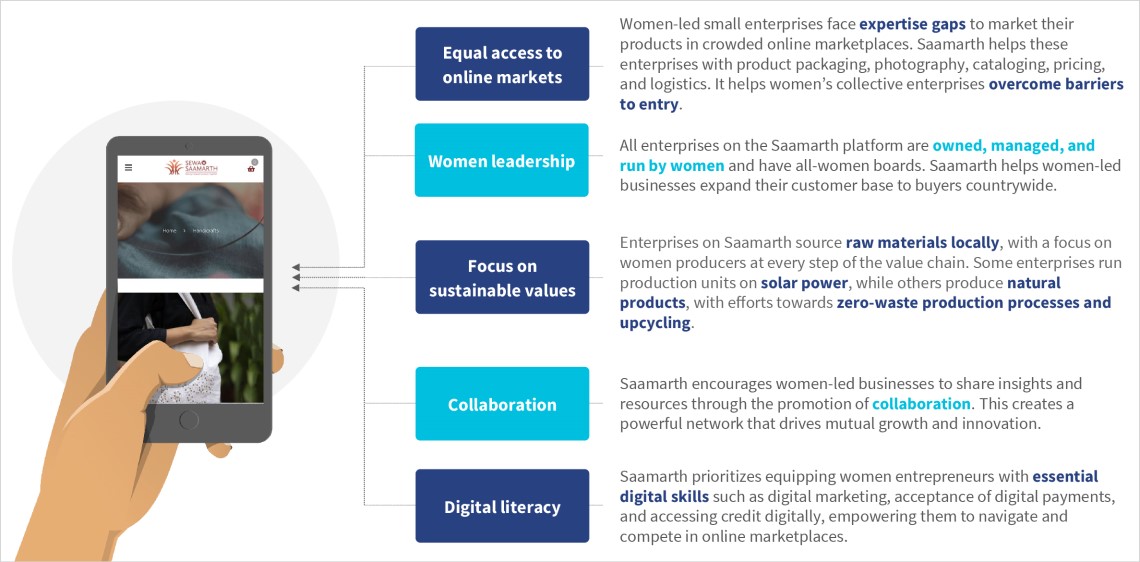

SEWA Saamarth is a platform developed by the SEWA Cooperative Federation. It seeks to help women’s collective businesses reach online and offline markets easily. This platform is for cooperatives promoted by SEWA Cooperative Federation, as well as other women’s enterprises across India that operate on cooperative principles. It allows them to sell their products online. SEWA Saamarth currently offers a variety of products, such as handicrafts, traditional snacks, and natural beauty products for hair and skin. It ensures that these women’s collectives are paid fairly for their products. Under this model, the platfoem does not charge any commissions or marketing fees to women-led businesses. At present, six women’s collectives sell their products through the SEWA Saamarth platform. These also include three SEWA-promoted cooperatives. The Saamarth platform is structured around five core values:

Saamarth currently sells handicrafts, snacks, and haircare products. It seeks to expand to different product categories to provide other women-led cooperatives and enterprises with a platform to sell their products online.

The way forward

MSC has been supporting SEWA Saamarth across various areas. These include a multichannel marketing strategy, development of a UI and UX that provides easy navigation and functionality, and ways to bring customer insights to refine its product, channel, pricing, and promotion strategy. MSC envisions that Saamarth will become a go-to-market access platform and launchpad for emerging and growing WLBs across India. Saamarth demonstrates three key strategies to bridge the market access gap for women’s enterprises:

- Digital solutions: Platforms, such as SEWA Saamarth, can help women’s enterprises overcome significant barriers in access to online marketplaces and connections with a broader range of buyers than they could have access to physically. SEWA Cooperative Federation also couples this initiative with capacity-building initiatives for the WLBs who are part of their collectives to enable them to grow. MSC has developed specific modules to help partners, such as the SEWA Cooperative Federation, complement their physical training with digital content. This digital content would work as a refresher for the WLBs on various platforms, such as WhatsApp, YouTube, and so on. The confidence women’s enterprises can gain from targeted capacity building can empower them to innovate, make bold decisions, and scale up their businesses to meet changing trends.

- Creation of an enabling business environment for women enterprises: We must go beyond connections with suppliers and buyers to truly bridge the market access gap for women’s enterprises. It must involve the skills required to excel in a rapidly changing e-commerce landscape. SEWA Saamarth supports women’s collectives with the skills needed to thrive in an online marketplace. SEWA Saamarth remains true to its values and maintains a strong sense of community among its collectives. It thrives on social capital, peer learning, and business support that WLBs provide each other.

- Communities of practice (CoP): Women-led enterprises face several unique challenges in their journey to build their businesses. In such a scenario, other women-led enterprises are the best fit to support, mentor, and nurture them. Saamarth strongly focuses on the creation of interlinked networks of women’s collective enterprises to share stories, discuss challenges, and collaborate on solutions. Networks of solidarity between women’s collective enterprises help them grow together and transform their ecosystems. They pave the way for new entrepreneurs to establish and scale their businesses. MSC has been working with Saamarth to build active CoPs, which will help women transmit information to one another and learn in the process.

Digital platforms, supportive ecosystems, and community networks level the playing field to forge a future where women’s enterprises flourish. Additionally, they create a new playing field where women’s businesses can grow, innovate, and lead. We pave the way for a more inclusive economy where women’s entrepreneurship is supported and celebrated as a cornerstone of global development when we harness these strategies. SEWA Saamarth has been striving to become better, efficient, and market-led with each passing day to become an established e-commerce platform.

The DIGIDHAN Mission’s impact on India’s digital payments ecosystem

This report explores the transformative effects of the DIGIDHAN Mission and highlights the notable 11x growth in India’s digital payments from 2017 to 2023. The mission, led by the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY), has fostered innovation, increased accessibility, and driven the adoption of digital payments across user segments. The report encapsulates the mission’s journey, achievements, and forward-looking perspectives to overcome challenges and harness opportunities to expand India’s digital payment landscape.