The struggle to overcome digital hesitancy

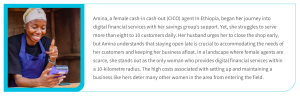

Subodh is a 44-year-old garment shop owner from rural Uttar Pradesh. He faces a tough choice. His son needs INR 5,000 (~USD 57) for a school competition. For this to happen, Subodh must make a long trip to the bank to withdraw money. This means he must close his shop and lose a day’s business. Although he owns a smartphone, Subodh avoids digital payments due to widespread stories of fraud. He is not confident about online transactions and thus chooses to go on the long journey to the bank, and in the process, sacrifices both time and earnings.

Figure 1: About Subodh and similar personas

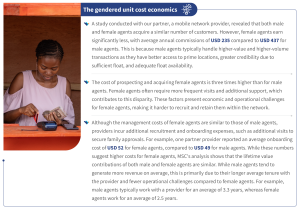

Similarly, Meera, a homemaker in rural Andhra Pradesh, has been struggling to repay INR 3,000 (~USD 35) for a microfinance loan that she had taken due to a family emergency. Although she owns a smartphone and has a linked digital wallet, she fears transaction failures, which stop her from using it. In her community, a missed loan repayment carries a social cost—a negative reputation. Overcome by doubt, Meera chooses to do nothing. Yet her fear holds her back and Meera chooses to rather risk financial penalties than attempt a digital transfer.

Figure 2: About Meera and similar personas

Subodh and Meera’s experiences highlight behavioral barriers that hinder the use of digital financial services (DFS). Because of such barriers, people hesitate to adopt DFS even though they may have access to smartphones. MSC’s six village story study found that only 14% of account holders used United Payments Interface (UPI)—the most accessible and affordable DFS facility available in India.

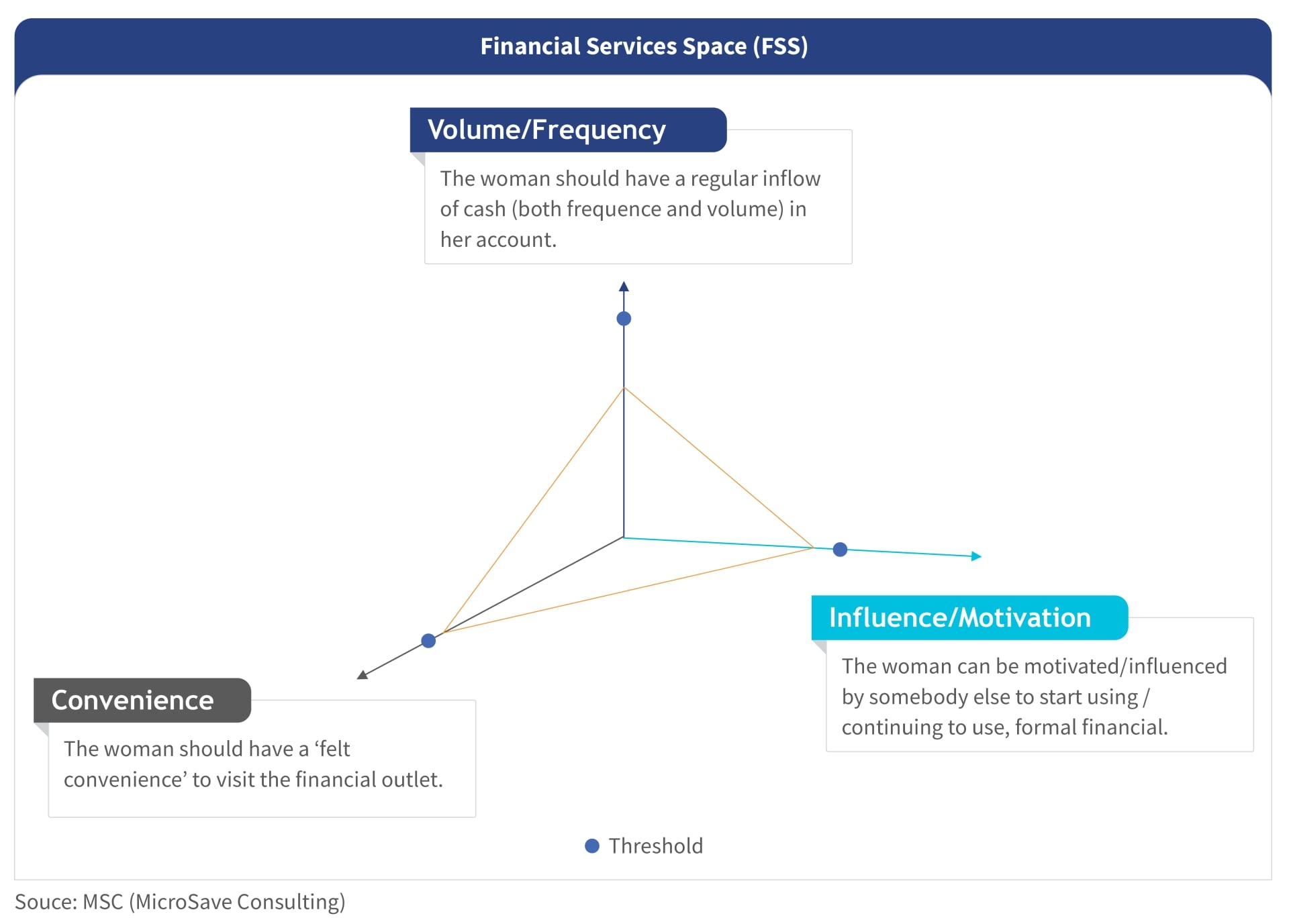

People like Subodh and Meera forego the potential for more convenient financial transaction platforms due to fear of fraud or making costly mistakes. Challenges, such as limited mobility, low financial literacy, and a lack of confidence, worsen these issues. Gender centrality acknowledges the differing financial needs and behaviors of men and women, shaped by social norms and inequalities. The following financial services space (FSS) framework highlights the dimensions for behavior change to enhance financial inclusion. It shows that the financial services space has not evolved for these customers, especially in the motivation dimension, which is highly influenced by multiple fears and awareness challenges, among other aspects.

Figure 3: Financial Services Space framework

As per the National Centre for Financial Education (NCFE), only 27% of the Indian adult population is financially literate, while most individuals only possess a basic level of financial literacy. Although initiatives, such as the “RBI Kehta Hai” campaign and initiatives by the Centre for Financial Literacy (CFL) and financial literacy centers (FLCs) promote financial awareness, they may not fully address the emotional barriers and fears associated with DFS.

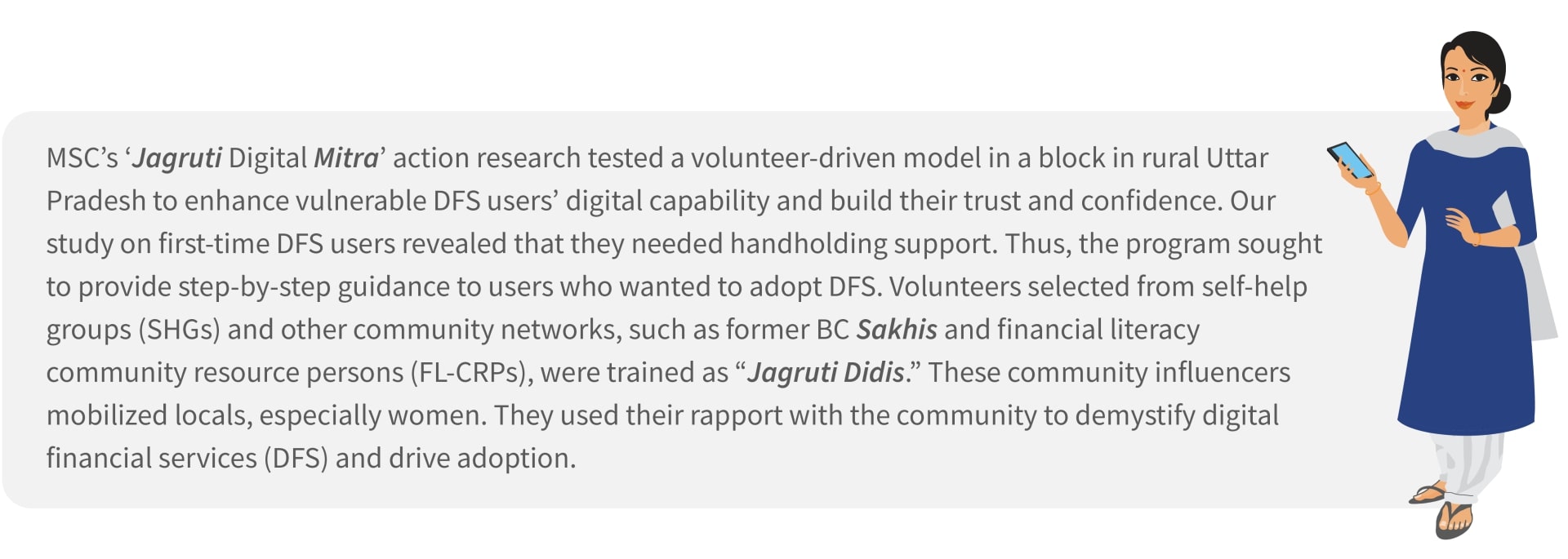

The Jagruti Digital Mitra intervention

Jagruti’s innovative content and delivery mechanisms

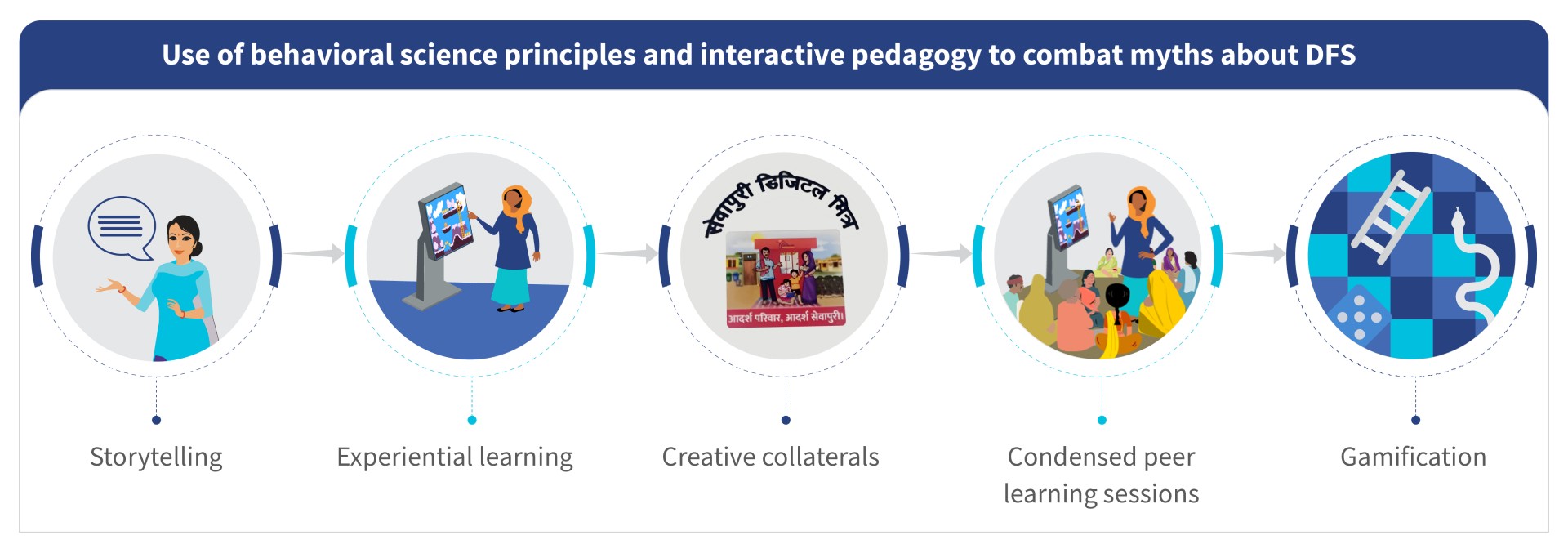

MSC applied its Market Insights for Innovation and Design (MI4ID) approach and infused behavioral science and human-centered design principles to craft engaging and relatable content.

Figure 4: Use of behavioral science principles and interactive pedagogy

Content: Harnessing emotions to drive financial decision-making

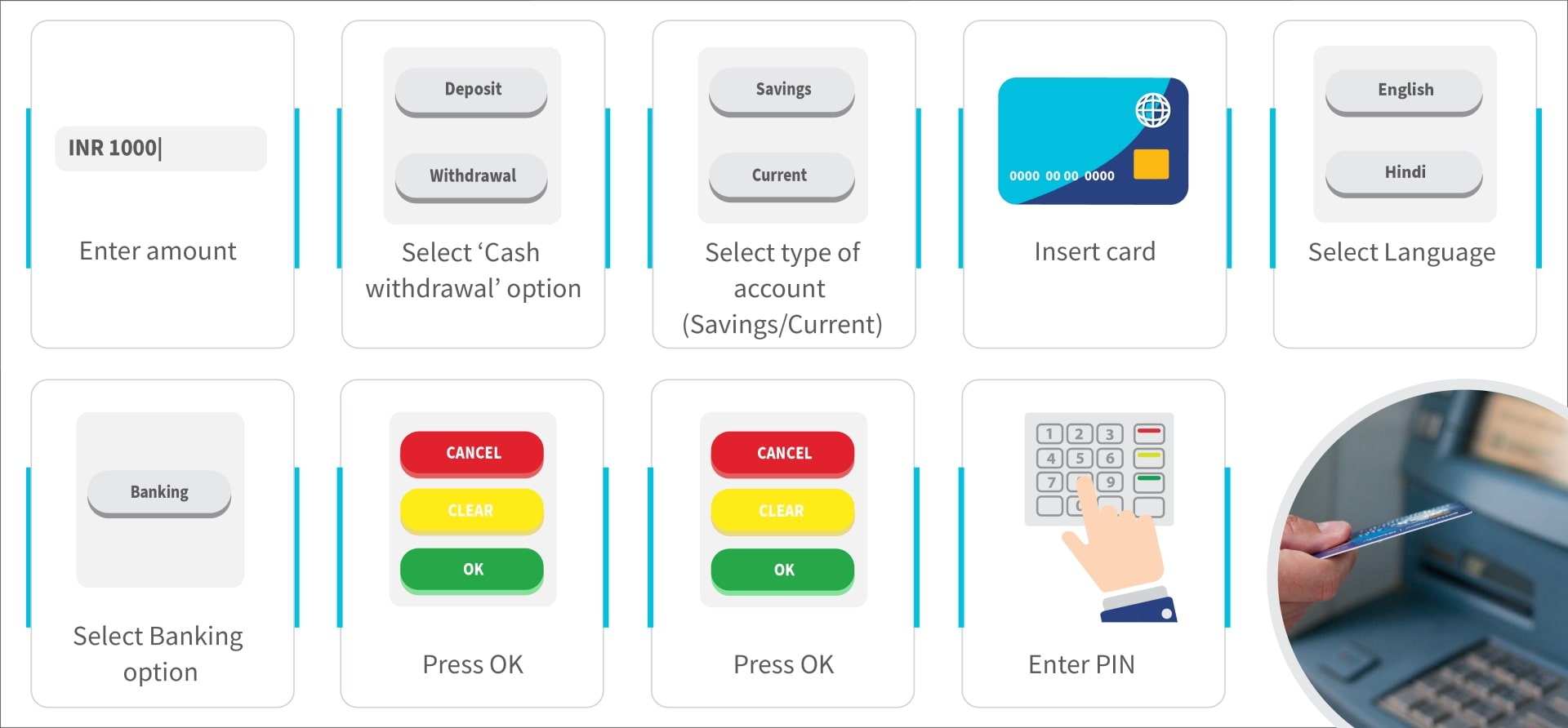

Emotions are an essential factor that shape attitudes and financial decision-making. Digital content designed to resonate with emotional responses can enhance user experience and drive meaningful action. MSC recognized this and created vibrant animated materials that featured relatable rural characters to engage audiences with limited literacy. These initiatives incorporated gamification and interactive techniques to integrate financial skills seamlessly into daily life. They helped debunk myths and build trust in financial services.

Figure 5: A flashcard activity- Conduct ATM withdrawal by rearranging the steps

Figure 6: Interactive and handy flashcards to share personal stories to influence behavior

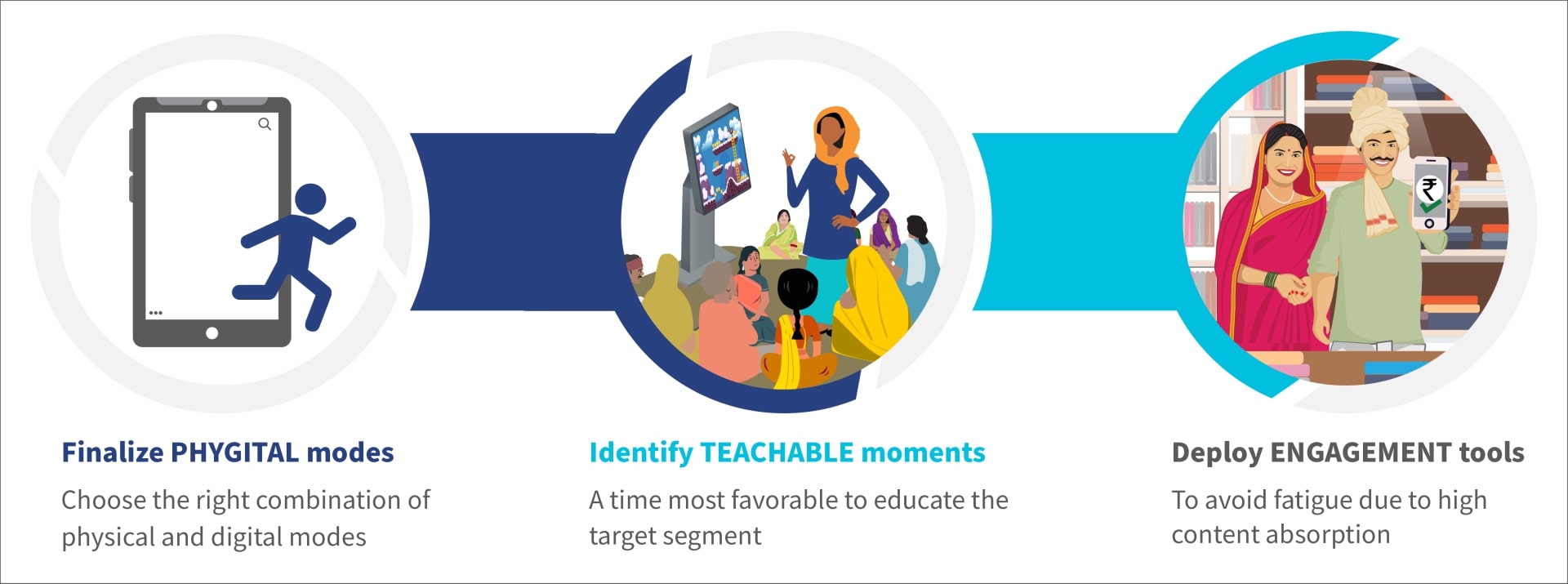

Delivery mechanism: Enhanced outreach through the PTE framework

The efficient delivery of digital financial capability (DFC) content requires customized channels built on the phygital, teachable, and engagement (PTE) framework. The Jagruti Digital Mitra program exemplifies this approach by combining physical and digital strategies to reach last-mile customers effectively. The Jagruti volunteers used interactive and engaging content and local stories that featured the program’s mascot, “Jagruti Didi,” to prevent content fatigue. The volunteers used teachable moments to engage with customers while they waited in queues outside bank branches, made loan repayments during self-help group (SHG) meetings, or participated in discussions on banking at gram sabhas (village meetings).

These interactions were strategically designed to enhance the adoption of digital financial services. The program integrated these innovative engagement approaches to introduce low- and moderate-income (LMI) users to digital financial services in a relatable and participatory manner. These users included women in particular. The integrated approach ensured inclusive access and sustained engagement to develop meaningful financial capability.

Figure 7: Use of the PTE framework to deliver digital financial literacy modules

Impact:

In just four months, 26 Jagruti digital mitras reached more than 2,300 community members. They focused on engaging 2,200-plus women. The intervention expanded outreach among female customers and built a network of community influencers and role models. These influencers supported volunteers in outreach activities, shared stories of change, and inspired potential beneficiaries to embrace digital financial services (DFS).

The program brought about noticeable shifts in women’s confidence when they dealt with DFS. As a Jagruti Didi remarked, “The unique tools provided to me to spread awareness enable me to instill confidence in women and conquer their DFS fears—whether it is the gamified snakes and ladders approach, storytelling, or the role-playing format of Ramesh Bhaiya and Jagruti Didi.”

Lessons learned: Empowering communities with a bottom-up approach

The bottom-up approach in the Jagruti Digital Mitra initiative demonstrates the transformative potential of localized and participatory strategies and community-driven models in overcoming barriers to DFS adoption. This approach equips volunteers with culturally resonant methods, such as storytelling, folk songs, and ritual design—a framework that uses symbols, narratives, and shared values. It builds trust and connects financial concepts to everyday experiences. Sustained volunteer engagement, supported by suitable incentives and ongoing support, is key to the long-term impact and scalability of such programs.

MSC recognized its importance and has integrated this approach into the financial inclusion training programs under the NITI Aayog’s Aspirational Block Programme (ABP). Furthermore, MSC has recommended that this financial education model be integrated into the block development strategies of India’s 500 aspirational blocks. Jagruti also inspired the design of capacity building on mobile financial services (MFS), agent banking, and e-commerce in Bangladesh for projects funded by the Gates Foundation, the Asian Development Bank Institute (ADBI), and the Griffith Asia Institute (GAI).

MSC’s approach to financial literacy or financial capability has emphasized the hands-on, practical application of tools to transfer knowledge, skills, and attitudes effectively. This strategy is designed to build financial capability through experiential learning, which reinforces that financial education and digital capability programs should enhance usage and not be limited to imparting theoretical concepts. We learned that continuous handholding and confidence-building elements are helpful as they address motivational barriers and expand the financial services space (FSS) for users.

Institutions must shift toward trust-based, community-led, and behaviorally informed models for widespread digital adoption. The Jagruti approach offers a replicable framework that ensures financial literacy is taught, lived, trusted, and applied.