Introduction

The Indian footwear market employs more than two million footwear artisans and was valued at USD 24 billion in 2022, with an annual growth rate of 6.7%. Approximately 20% of its employees are from Agra, Uttar Pradesh. Agra caters to 65% of the domestic footwear demand of India. However, during COVID-19, almost 70% of the footwear manufacturers shut shop due to inadequate business. This blog looks at Kaarigar Mandi, a footwear startup in Agra, and its effort to preserve traditional handmade footwear manufacturing while securing the livelihood of the footwear artisans.

We spoke to a footwear maker from Agra to understand the problem better. Saurabh is a footwear master artisan who employs six other artisans from his community. He has been struggling ever since several shop owners who sold footwear refused to buy from him. He worked with a bulk footwear buyer. But lately, the buyer has not placed any orders with him. He rued, “Buyers say they do not know me, so they cannot trust me.” The lack of buyers forced Saurabh to explore others to sustain his business. Saurabh is now worried about getting work for himself and the artisans working under him, as no new buyers have been entertaining him.

The graphic below describes different problems Saurabh and other master artisans like him face due to an uncertain business environment.

Kaarigar Mandi is a startup that works with such master artisans. It helps them standardize their production through quality checks, capacity building, and greater transparency in the footwear manufacturing process. This standardization helps them match the needs of bulk footwear buyers. The startup aspires to build an aggregator platform between the artisan community and bulk footwear buyers. It seeks to support the artisan community through raw materials, job stability, timely payments, and linkage to a formal credit ecosystem.

The light bulb moment

Kaarigar Mandi was founded in 2019 Ankit Kumar, Gagan Mukhi, and Dr. Hifza Afaq. Before Kaarigar Mandi, Ankit used to work as an e-commerce consultant for domestic footwear brands in Agra. He met various footwear artisans in the factories during his stint. These artisans owned small handmade footwear manufacturing units. But rapid industrialization in the sector led them to lose their clients and business. During conversations with these artisans, Ankit realized that their footwear craft was high quality. Yet sub-par raw materials and lack of standardization led to low-quality end products.

Kaarigar Mandi was founded in 2019 Ankit Kumar, Gagan Mukhi, and Dr. Hifza Afaq. Before Kaarigar Mandi, Ankit used to work as an e-commerce consultant for domestic footwear brands in Agra. He met various footwear artisans in the factories during his stint. These artisans owned small handmade footwear manufacturing units. But rapid industrialization in the sector led them to lose their clients and business. During conversations with these artisans, Ankit realized that their footwear craft was high quality. Yet sub-par raw materials and lack of standardization led to low-quality end products.

Ankit recognized this fading craft’s potential as a lucrative business venture and founded Kaarigar Mandi as an end-to-end footwear supply chain platform. He changed his focus to offer high-quality products to the artisans to enable them to create superior-quality footwear. He also introduced technology and professionalism to footwear manufacturing in the supply chain. The technology increases standardization and transparency in the supply chain to enable the sale of handmade footwear to bulk buyers and consumer brands.

Ankit brought in his friend Gagan, who had footwear manufacturing experience, as a cofounder. Gagan started to handle the operations and artisans’ relationship with Kaarigar Mandi. Later, his wife, Dr. Hifza, joined the founding team as the technology founder.

The unique pitch

- Kaarigar Mandi facilitates financial support to artisans and connects them with lenders. These lenders can provide easy, low-cost credit to manage the artisans’ capital requirements. One such platform is Credochain, part of the Financial Inclusion (FI) Lab’s earlier cohort.

- Kaarigar Mandi conducts multi-level quality checks to deliver footwear with less than a 1% rejection rate for bulk footwear buyers. Thus, it builds trust among its customers.

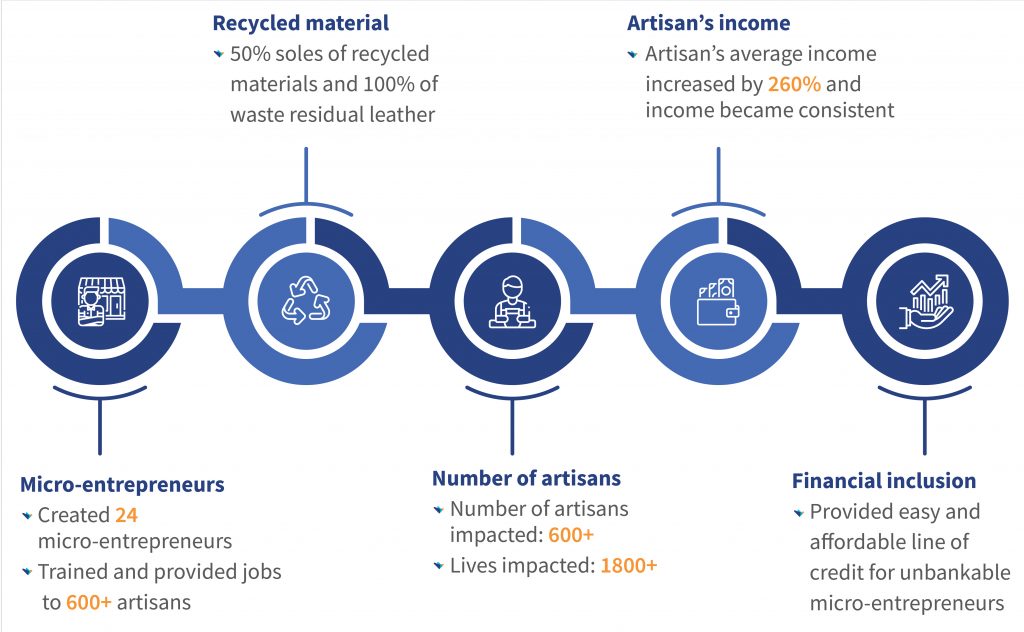

Impact on artisans

Kaarigar Mandi works with more than 600 footwear artisans in Agra. These artisans aspire to grow their microenterprises with the startup’s support. They are keen to learn how to manage their businesses efficiently. MSC’s field research highlights how the artisans’ engagement with Kaarigar Mandi has helped them get a steady income and upgrade their skills to make better footwear. Kaarigar Mandi has also partnered with NGOs, such as Ek Pahel in Agra, to train female artisans to make quality footwear and provide them with work to earn additional household income households.

The empathy, affection, and respect Kaarigar Mandi extends to its artisans is the key differentiating factor of its engagement. “My husband is a footwear artisan and was the only breadwinner for the family. Two years back, he got severely ill. My son and I struggled to survive when we met Gagan bhaiya from Kaarigar Mandi. He gave us an instant loan to care for my husband’s illness, trained me to manufacture footwear, and employed my 16-year-old son as an admin support in their office. He has changed our lives and treats us with respect—just like a younger brother,” smiles Shanta, a female footwear artisan.

Roadblocks ahead

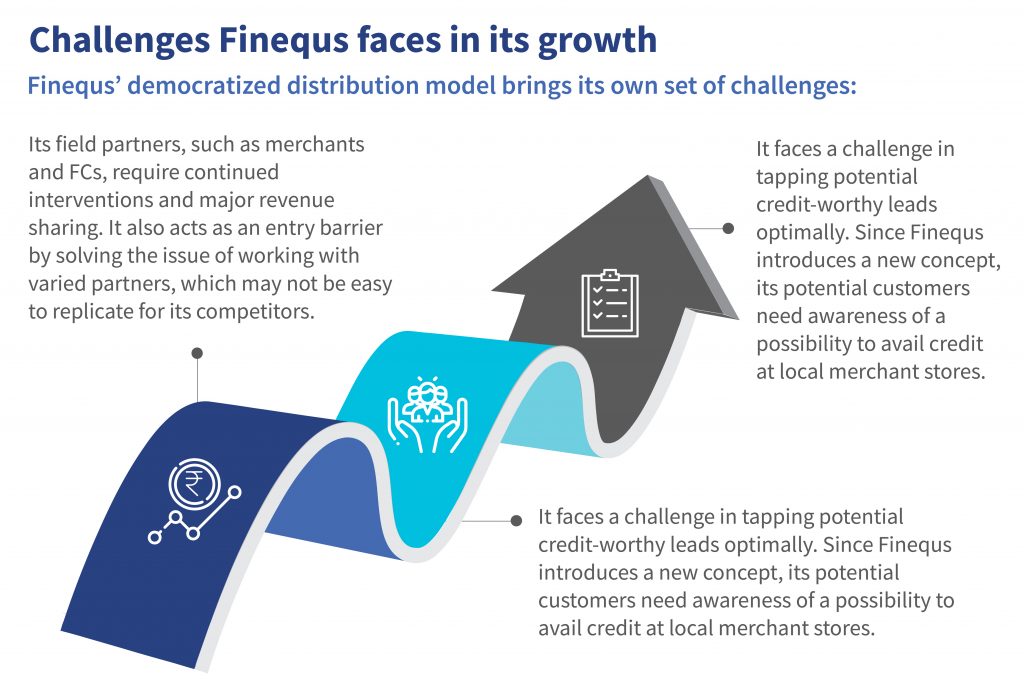

Kaarigar Mandi faces two critical roadblocks in its growth journey:

- First, it struggles to retain skilled artisans who often leave the handmade footwear industry when they do not have steady work and seek other roles, such as factory workers or street vendors. As a result, it has to spend more time and money to recruit and train new artisans. Sometimes, it even pays them in advance to cover their weekly or monthly salary before they start work.

The second challenge for Kaarigar Mandi is that the footwear industry in India comprises traditional and close-knit businesses. Large institutions as well as small-scale footwear buyers usually have long-standing relationships with their preferred vendors. These vendors can meet the buyers’ specific needs. Kaarigar Mandi faces resistance as a new entrant in the footwear business.

It had to invest more time and effort to build trust among bulk footwear buyers. In response, Kaarigar Mandi manufactures small batches of footwear in various designs to be used as samples for various institutional buyers. However, while such small-batch manufacturing is essential to create a market for Kaarigar Mandi, the approach negates economies of scale. It is thus not sustainable in the long term.

Support from MSC’s FI Lab

MSC’s FI Lab’s support to Kaarigar Mandi has been strategic in backward and forward linkages to address these roadblocks.

- MSC collaborated with Kaarigar Mandi to identify artisans’ problems and assess ways to support them. The team interacted with the artisans directly and collected field insights to enhance their relationship with Kaarigar Mandi. MSC suggested several mitigation initiatives. These included upgrading artisans to take work from various firms, including Kaarigar Mandi, capacity building on business and inventory management, and standardization of quality checks. Better quality checks would allow Kaarigar Mandi to establish strong ties with the artisan community and become their preferred partner for footwear production.

- The MSC team explored the emerging opportunity to supply footwear to D2C (direct-to-consumer) brands to generate more business. The team helped Kaarigar Mandi reposition itself as a quality supplier to generate business from the D2C footwear companies. MSC’s assistance will allow Kaarigar Mandi to create more business and provide its artisans with a consistent line of work. In the first month of Kaarigar Mandi’s repositioning through a social media campaign, MSC helped it get more than 60 leads from footwear D2C brands.

MSC designed these two interventions to address the two key, interrelated challenges of artisan churn and limited buyers for products. D2C footwear is a growing segment, and if Kaarigar Mandi can position itself well, the artisans will stand to gain the most. MSC’s support continues to generate online leads through extensive social media marketing to position Kaarigar Mandi as a reliable, high-quality brand among D2C players.

Way forward

Alongside its business goals, the startup also wants to preserve the traditional art of footwear manufacturing, arrest migration, and build the local economy. It plans to expand its artisan network to 5,000 in two to three years. It also seeks to provide them with continuous work and increased engagement throughout the year. Thanks to Kaarigar Mandi’s efforts, artisans like Saurabh can now look forward to preserving their skills and aspire toward a brighter future.

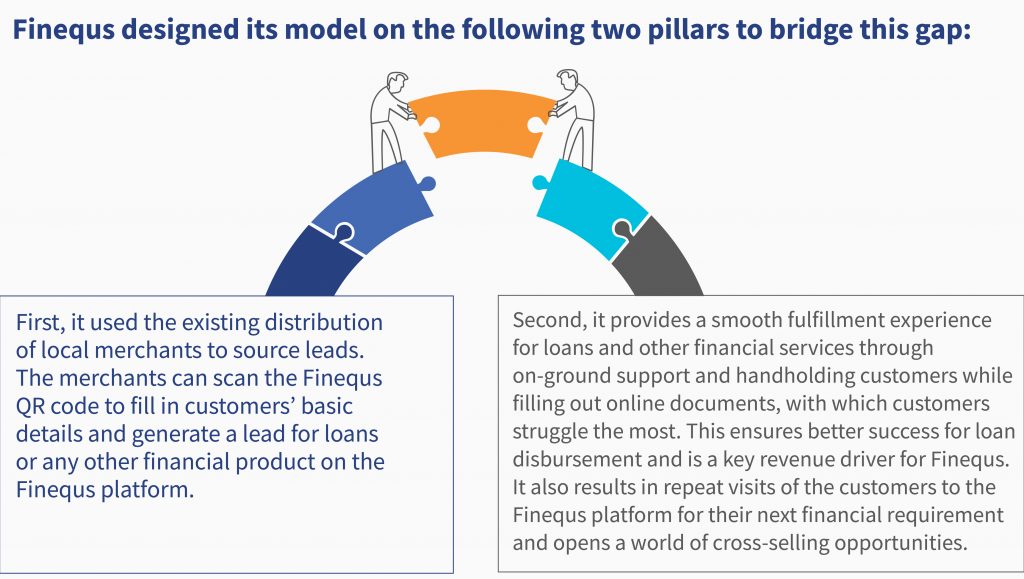

Krishnan used his rich and varied banking experience across premier private and multinational banks to understand the limitations of the traditional financial ecosystem to reach the underserved segments of society. Even the FinTechs operating for a considerable time cannot reach the masses. Gaps, such as trust in the digital medium and the savviness of users to avail digital loans of their own, limit the uptake of formal credit products. Finequs saw this opportunity and decided to operate at the

Krishnan used his rich and varied banking experience across premier private and multinational banks to understand the limitations of the traditional financial ecosystem to reach the underserved segments of society. Even the FinTechs operating for a considerable time cannot reach the masses. Gaps, such as trust in the digital medium and the savviness of users to avail digital loans of their own, limit the uptake of formal credit products. Finequs saw this opportunity and decided to operate at the

The journey of MAKSPay founders

The journey of MAKSPay founders

The FI Lab’s support

The FI Lab’s support