This blog is about a startup under the Financial Inclusion (FI) Lab accelerator program’s fourth cohort. The Lab is supported by some of the largest philanthropic organizations across the world – Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, J.P. Morgan, Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, MetLife Foundation, and Omidyar Network.

British mathematician and entrepreneur Clive Robert Humby coined the phrase “Data is the new oil” in 2006. Michael Palmer of the Association of National Advertisers expanded on Humby’s quote by saying, like oil, data is “valuable, but if unrefined, it cannot be used.” As Digital India marches forward, the importance of data is now greater than ever before.

With the rapid digitalization of the country, the role of digital ecosystems and digital infrastructure has become paramount as they complement our physical infrastructure to address the needs of its socioeconomic development. Inclusive digital ecosystems can help scale the usage of financial products and make financial inclusion more meaningful.

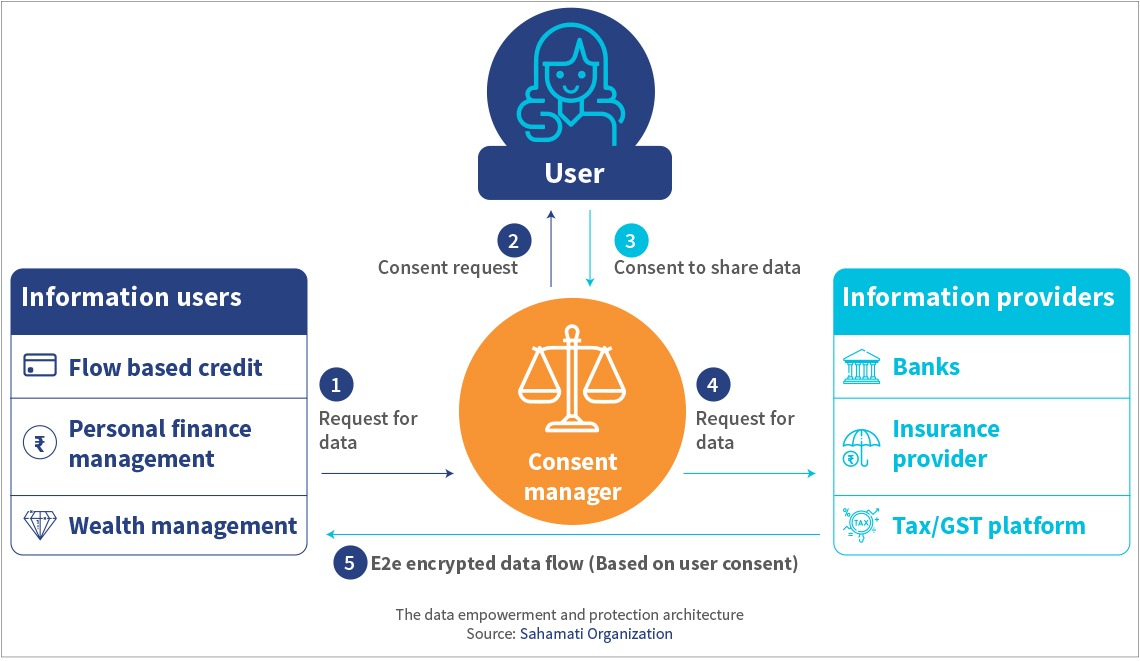

For example, 90% of adults having a bank account mean nothing when 45% are dormant. An inclusive digital ecosystem provides faster, better, and cheaper ways to access financial services. The government and industry regulators are leading this transformation across multiple layers of the India Stack. From Aadhaar to the current open API program, four distinct layers have played a crucial role in India’s digital foundation and evolution. The consent layer is the fourth and final piece in the India Stack. It brings the National Open Digital Ecosystem (NODE) in place by building Data Empowerment and Protection Architecture (DEPA) framework.

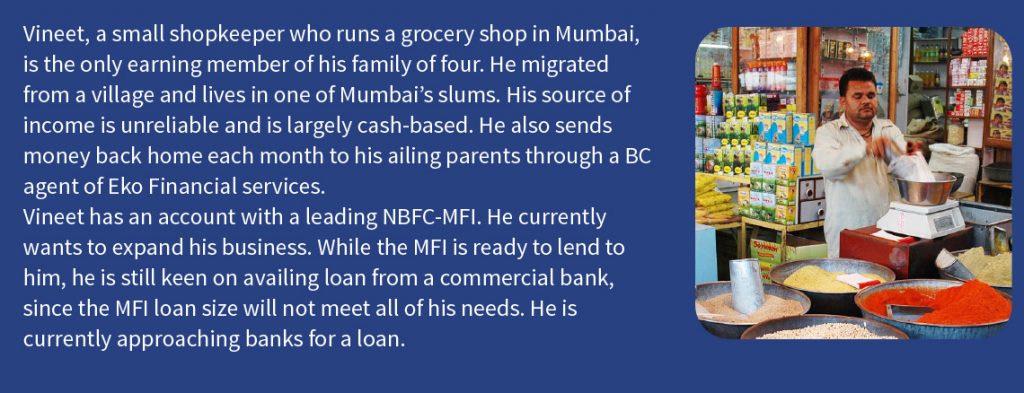

NODE will enable innovators to build financial inclusion-focused solutions across various sectors on top of open standards, open application programming interfaces (APIs), and other regulated architecture for the public good. This new consent framework will use the data for good while maintain consumer privacy. We highlight how such a framework used by different stakeholders can benefit someone like Vineet, a kirana store owner in Mumbai.

In such cases, the role of account aggregators (AA) and technical service providers (TSPs) assumes critical importance. The Reserve Bank of India established an “NBFC account aggregator.” in 2017. This regulated entity aggregates and provides information on various accounts held by a customer in different banking entities. Based on the customer’s consent, the AA will retrieve, consolidate, and organize data about the multiple types of financial engagement by a customer among various financial products, such as insurance and mutual funds.

Under NODE’s consent architecture, Vineet can use an account aggregator app to fetch his financial data from different like Eko (remittance transactions) and NBFC-MFIs (loan account). He can share these transactions fully encrypted with any financial information user (FIU) like a commercial bank. The FIUs can use this information to assess his creditworthiness and approve his loan application. A technical service provider (TSP) supports these financial institutions to become a part of the framework as FIPs or FIUs by building their foundation modules to connect with account aggregators in the ecosystem.

Finarkein analytics plays the role of TSP here, where they support the financial institutions to on-board the DEPA framework by developing these modules. On top of this, Finarkein provides its data analytics engine to ensure efficient use of data by financial institutions to cater to a broader range of customers from the low- and moderate-income (LMI) segment. As an enabler, the startup plays an invisible role by quietly developing the back-end technology infrastructure to improve processes and renew legacy systems of financial institutions in the ecosystem.

The light bulb moment

While working for an IT company in Pune, Nikhil and Dheeraj, two experienced Computer Science Engineers, shared their beliefs around data sharing and data privacy. The duo was mainly concerned with how through privacy-intrusive techniques in the current environment.

As some public digital goods like the DEPA framework were coming to life, the duo realized that the NODE itself had specific gaps and limitations regarding data consumption and management, which innovators like themselves could potentially solve. With this DEPA framework, every entity looking to consume data has to rely on account aggregators for the data and the user’s consent. The FIU can directly use this data, or a participating TSP can help generate granular insights on the user. Realizing that they could operate in this specific domain, they started Finarkein and hired a few developers to build “Flux,” a data analytics platform.

The birth of Flux—the unique pitch

The Flux platform empowers developers to iterate, deploy, and experiment rapidly to build data-driven experiences in the financial services industry. The potential clientele for Flux in India encompasses 200-odd banks, 9,500 NBFCs, and thousands of other companies that will need technology to help them adapt to the AA paradigm. As a TSP tool, Flux brings solutions for them to build the middleware to help:

- FIP and FIU share and consume data in of account aggregator framework

- FIP and FIU manage customer consent and customer data (data governance and data security products)

- Financial institutions to provide good AA UI/UX flows on their apps

Besides these opportunities around AAs themselves, Flux also has several options to build software products and offer services for cash flow lending, personal finance management, and UPI applications. Financial institutions are yet to fully adopt the India Stack’s consent layer with the DEPA framework as financial information providers and financial information users. Finarkein wants to support financial institutions that cater to LMI customers as an early TSP in the market. This last layer for the “democratization of financial services” focuses on using various data points to support incumbent and new-age startups to develop and deliver innovative solutions. Onboarding the DEPA framework is still a wait-and-but as one of the first TSPs, Finarkein seeks to target specific players with an LMI customer base to improve the accessibility of financial services for people like Vineet.

The evolution: Identifying and overcoming challenges

A significant challenge for Finarkein has remained the development of its value proposition. The space is nascent, and early adopters remain limited in . The Finarkein team has found it challenging to find the right direction for strategic expansion. Like with any other startup, limited resources have been another challenge. The FI lab supported Finarkein’s team to build its value proposition for potential clients in the lending space. MSC analyzed and provided insights on targeting these clients with specific use cases and pitches based on their needs and current data analytics capability. This technical assistance has helped Finarkein build a stronger, more robust pitch for its prospective clientele, mainly the MFIs and SFBs.

Finarkein plans to elevate Flux into an innovative playground for developers and entrepreneurs who cater to the LMI segment, not only in financial services but also in the health space. It wants to drive the adoption of the consent-based data layer, which is India Stack’s final layer. It is focused on building a developer community to transform the space with disruptive products and services and lead the growth of open digital ecosystems in India. In their work as a TSP, Finarkein wants to ensure that everyone can enjoy the benefits of this digital infrastructure—notably smaller entrepreneurs like Vineet who need it the most.

This blog post is part of a series that covers promising FinTechs that are making a difference to underserved communities. These startups receive support from the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program. The FI Lab is a part of CIIE.CO’s Bharat Inclusion Initiative and is co-powered by MSC. #TechForAll #BuildingForBharat

ChitMonks works with chit fund companies and several different stakeholders in the chit fund industry. These stakeholders include regulators and other enablers in the chit fund ecosystem. ChitMonks started in Telangana, where it designed, developed, and implemented its product while lending support to the state government, its regulated chit fund companies, and their subscribers. It transformed the entire chit fund infrastructure from manual systems to a blockchain based system. Progressing from Telangana, ChitMonks has already started work in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. Today, it is in talks with the state governments and regulators of a few more Indian states to expand its reach.

ChitMonks works with chit fund companies and several different stakeholders in the chit fund industry. These stakeholders include regulators and other enablers in the chit fund ecosystem. ChitMonks started in Telangana, where it designed, developed, and implemented its product while lending support to the state government, its regulated chit fund companies, and their subscribers. It transformed the entire chit fund infrastructure from manual systems to a blockchain based system. Progressing from Telangana, ChitMonks has already started work in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. Today, it is in talks with the state governments and regulators of a few more Indian states to expand its reach.

Ravi Varma, an auto-rickshaw (tuk-tuk) driver from Bengaluru, could not save regularly. However, since the

Ravi Varma, an auto-rickshaw (tuk-tuk) driver from Bengaluru, could not save regularly. However, since the  Founder

Founder

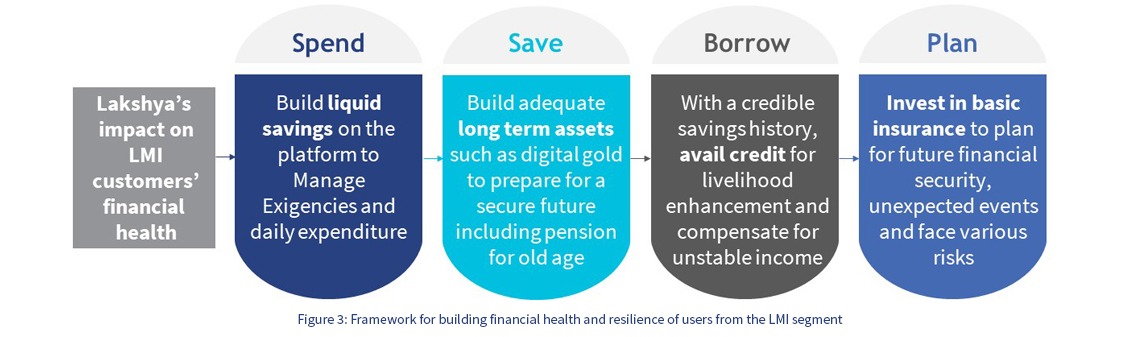

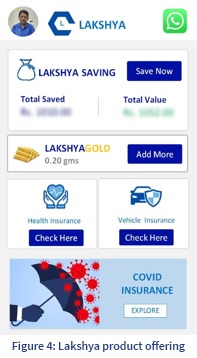

After understanding this segment’s financial need of providing credible sources of savings, Lakshya developed a solution that would meet their need for customized financial products. Lakshya plans to build on this initial work to transform it into a ubiquitous platform for other segments.

After understanding this segment’s financial need of providing credible sources of savings, Lakshya developed a solution that would meet their need for customized financial products. Lakshya plans to build on this initial work to transform it into a ubiquitous platform for other segments.