For savings groups, the digital transformation of savings management and credit processes is fundamental in breaking the barriers around account opening, client onboarding, entrepreneurship training, loan application, analysis, approval, and disbursement. This video focuses on why it is important for financial institutions to digitize savings groups, challenges that savings groups experience as they go through this transformational journey as well as the benefits that these organizations stand to gain by moving away from manual operations toward more digitized solutions. Watch and learn.

Blog

Budget 2020: How FM Nirmala Sitharaman’s dictum ‘Nari tu Narayani’ can actually work

- With India’s 2020 budget coming up around the corner, there is a reasonable possibility of more schemes targeting women being placed on the table.

- The flow of credit into the SHGs to meet the provision of Rs 5000 worth of overdraft facility for every SHG member, has not taken wing yet.

The Government of India in its 2019 Budget put sizeable allocations (close to Rs 1.4 trillion) to programmes designed for empowering women. In fact, the Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman’s dictum ‘Nari tu Narayani’, was virally lauded.

Notable among these initiatives were the Nirbhaya Fund, Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana, Integrated Child Development Services Scheme (ICDS), and immediate Rs 5,000 overdraft facility for all SHG members.

The government’s schemes seeking to benefit women on a large scale have been met with mixed results in the past. An example of success is that of the Pradhan Mantri Ujjawala Yojana (PMUY), which has impacted the lives of 80 million women. Our studies have found that PMUY has been able to change the quality of their lives by providing them with clean fuel. However, the flow of credit into the SHGs to meet the provision of Rs 5000 ($70.3) worth of overdraft facility for every SHG member, has not taken wing yet.

At the outset, it is critical to realise that the end-beneficiaries of these programmes are women — who unlike men face constraints in mobility thereby limiting their exposure to the digital evolution and/or simple market dynamics. In addition to this, community-based gender stereotypes affect women’s independent decision making. Furthermore, many programme designs do not foresee unintended consequences. Imagine a woman having to travel for 15 km on the rear end of her husband’s bicycle to withdraw a direct benefit transfer (DBT i.e. the mechanism of transferring subsidy into a beneficiary’s bank account). This token of financial independence comes at the price of added workload and increased dependence — greatly defeating the point of her being advantaged by the scheme.

Programmes check-list

The success/failure of implementing a programme for women can be related to its structural design with respect to the intended beneficiary. Often the programmes look at ‘women’ as a homogenous user group, but our research shows that it actually is segmented into sub-groups with distinct social and economic characteristics. MSC’s concept of Financial Services Space gives an overall picture of such segmentation with regards to a financial inclusion programme. The FSS lens shows that women can be classified into six discrete user groups namely excluded, dormant, proxy, irregular basic, regular basic, and advanced, depending on their extent of financial inclusion.

Also, a programme cannot serve women unless it considered the context of prospective participants. These include factors such as a) her preparedness, and capacity to adopt the programme b) her prior experience/exposure to similar products/scheme that the programme offers c) her economic life, and d) social norms which influence her behaviour. This also explains the complex outcomes which pilot studies on subsidised-ration (available at PDS shops) replacement with DBT have shown. For example, in Puducherry, only 68 per cent of women (who were supposed to receive the DBT) had their bank account seeded to Aadhaar.

With India’s 2020 budget coming up around the corner, there is a reasonable possibility of more schemes targeting women being placed on the table. For a policy or programme to work for women, it must run past a quick check-list: 1) Are the programme designers gender sensitised? 2) Has enough information to gauge women’s socio-cultural context been collected? 3) Has the capacity/exposure of the end-user been taken into account? and 4) Has the scope for the fallout, and subsequent rectifying action, been accounted for? This will definitely make programmes gender centric and successful in serving women.

The blog was also published on CNBC TV 18 on 27th of January, 2020

Nutrition literacy: Charting a new path forward

In our previous blogs 1 and 2 in this series, we discussed the sub-par nutrition statistics of India along with a lack of diversity in the dietary habit among people. We also looked at the steps the government should take to address these issues. In this blog, we highlight the importance of nutrition literacy.

MSC concluded a study in August, 2019 that assessed the nutritional gaps at the household level. The study revealed that while a minimal number of beneficiaries faced a shortage of food, the diet across all demographic groups was deficient in major macro and micronutrients. This deficiency can be attributed to the lack of diversity in the diet of the beneficiaries. People, in general, only possess a traditional knowledge of nutrition. Hence, nutrition literacy and constant “nudging” is required to improve the overall nutritional outcomes.

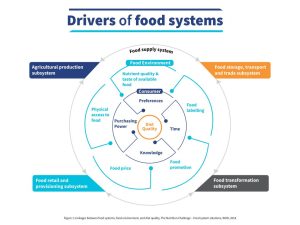

Multiple variables, termed “lifestyle factors” influence the eating habits and food choices of people, which in turn affect nutritional intake. We found that people prefer readily-available food items and the availability is influenced by agricultural economics, logistics, and market dynamics. The second level of factors that influence choice includes price, packaging, taste, and access while the third level includes knowledge, affordability, and personal preference. The diagram below illustrates the factors involved in the food supply system that affect the nutritional outcomes for individuals.

Unhealthy diets often result in malnutrition and are the cause of more adult deaths and disabilities globally than the use of alcohol and tobacco. The current food systems in India do not provide diverse and healthy diets1 for the beneficiaries and this contributes to malnutrition. All segments of society, particularly the low and middle income (LMI) segment, grapple with malnutrition. The triple burden of malnutrition—stunting and wasting, anemia, and obesity are common in women, men, and children but are especially prevalent among women and children.

Policymakers around the world have started to take the problem seriously. The annual expenditure of 25 countries for nutrition-sensitive and nutrition-specific allocations has increased to USD 16.2 billion 2,3 , in 2018. Evidence from across the globe suggests that an improved income and the availability of quality food does not necessarily translate into a marked increase in the nutrition indicators of the LMI population 4. People tend to focus on quantity rather than the quality of consumption as they are unaware of good nutrition practices.

Initiatives by the government and gaps in implementation

The Government of India (GoI) administers various programs to address issues in hunger and nutrition, such as PDS, Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), Mid-day Meal (MDM), Poshan Abhiyan, Anemia Mukt Bharat, and the Rashtriya Poshan Maah (National Nutrition Month). While these initiatives have admirable objectives, the focus on nutrition and monitoring needs to be improved. Food fortification is a possible method to improve nutrition but it is not a desirable solution in the long term as it does not substitute for a wholesome diet. 5,6 The government also runs programs like the Village Health Sanitation Nutrition Committee (VHSNC) that use a “softer” approach to undernutrition. However, several reports highlight the gaps in implementation with regard to training, support, and monitoring in these programs 7,8,9,10.

The primary research conducted by MSC revealed that a lack of variety in the diet, along with poor choices in food, leads to high consumption of carbohydrates. People are often misled by advertisements that flaunt a “healthy” or “nutritious” label. Nutrition literacy 11 is an important lever to ensure that the beneficiaries reap the full benefits of various government initiatives and this can ultimately help drive the desired change.

Charting a new path forward

In addition to changes, such as food fortification and the introduction of variety in the PDS food basket, the government should also focus on nutrition literacy. The proper dissemination of information will help ensure the uptake of a variety of grains through PDS. The principles of behavioral science should be used to introduce nutrition literacy and ensure desirable solutions. We have provided some recommendations below to incorporate nutrition literacy through the existing channels:

i. Use the concept of orality 12 to display pictorial information on the ration cards about the healthier food items available in the PDS basket along with their associated benefits.

ii. Use the mobile numbers linked to the beneficiaries to create a messaging (SMS) platform to promote content related to health and share interactive voice response.

iii. Provide better training on nutrition to government workers at the village level, such as Anganwadi workers and ASHAs. These frontline workers should explain the health benefits of different food items to the adults and the children and use appropriate channels to disseminate tailored content to their audience, such as songs and stories for children. Anganwadi workers should use tablets to deliver messages using behavioral nudges. 13,14

iv. Strengthen initiatives like the School Health Program and monitor their implementation closely. Expand the scope of the program to include private schools to increase the outreach. Use behavioral nudges and innovative learning techniques in the curriculum, such as interactive games and competitions.

v.The government should increase its workforce to ensure the proper implementation of initiatives, such as the Poshan Abhiyan, Village Health Nutrition and Sanitation Committee, and the Scheme for Adolescent Girls. Rather than targeting just the vulnerable groups, the focus should expand to include men of the household and the elderly who may have a larger say in the food decisions in a family.

Over the past decade, nutrition has received much-needed recognition. Knowledge sharing on the topic has been significant, particularly among the middle and upper classes. However, this awareness and knowledge have not percolated to the LMI segment where undernutrition remains a challenge. A possible solution is to use Social Behavior Change Communication (SBCC) to influence the behavior of the people since it has proven more effective than traditional communication. The concept of nutrition should be introduced to the masses at an early age to create awareness and encourage acceptance. This would lead to good practices in their diets, so the evils of undernutrition can finally be stamped out.

References:

- The Nutrition Challenge – Food system solutions, WHO, 2018.

- Global nutrition report.

- This does not include food security programs, such as the public distribution system of India that alone has an annual budget of around USD 25 billion.

- Narrowing the nutrition gap.

- Guidelines on food fortification with micronutrients, WHO, FAO, 2006.

- Behavior change for better health: nutrition, hygiene and sustainability, BMC Public Health, 2013.

- Are village health sanitation and nutrition committees fulfilling their roles for decentralized. health planning and action? A mixed methods study from rural eastern India, BMC Public Health, 2016.

- Assessment of Village Health Sanitation and Nutrition Committees of Chandigarh, Indian Journal of Public Health, 2017.

- Assessment of village health sanitation and nutrition committee under NRHM in Nainital district of Uttarakhand, Indian Journal of Community Health, 2013.

- Poshan Abhiyan, Government policies and interventions for development in various sectors and issues arising out of their design and implementation, Insights Mindmaps, 2018.

- Nutrition literacy refers to the set of abilities needed to understand the importance of good nutrition to maintain health.

- Orality is the concept of simplifying communication to make it easy to understand for someone who does not read or write. It is an effective tool that focuses on the receiver and makes messages relatable and retentive.

- Study identifies the best healthy eating nudges, Eurekalert, 2019

- The Rise of “Nudge” and the Use of Behavioral Economics in Food and Health Policy, Mercatus, 2015

An apple a day may not keep the doctor away—the importance of dietary diversity

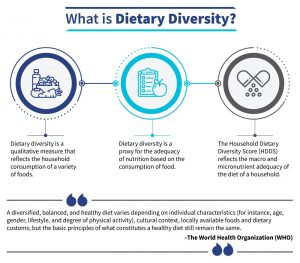

MSC undertook a study in July, 2019 to assess the nutritional gaps in households 1 served by the Public Distribution System (PDS)2. We conducted the study in Ranchi district of Jharkhand state and West Godavari district of Andhra Pradesh, India. The respondents of the study were women—most of them belonged to households where the primary breadwinner was a wage-laborer who carried out “heavy work”3. Our study revealed that the target populace severely lacked dietary diversity 4.

The respondents reported that staple grains, such as rice and wheat formed a large part of their daily food consumption with little to no inclusion of pulses, vegetables, meat, or fruit. Most respondents did not even consume dairy products.

Various socio-economic challenges hampered the dietary diversity of the respondents. The primary challenges were the availability and affordability of food. For example, dairy farming was not prominent in the region where we conducted our research and many fruit and vegetables were not cultivated locally. Despite the availability of low-cost diet alternatives in local markets, respondents were unaware of their nutritional importance.

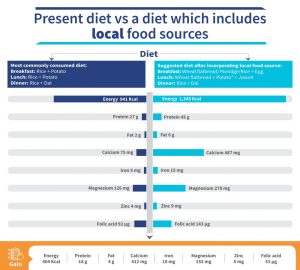

In the table given below, we compare the nutritional outputs of the most commonly consumed diet to a diet that incorporates local food sources.

Note: All the values are calculated using standard recipes as stated by the National Institute of Nutrition (NIN).

*Replacing potato with local green leafy vegetables will further increase the nutritional intake significantly, even if it is three times a week.

#Jawa is a healthy drink made of Ragi (Eleusine coracana or finger millet) also known as Ragi malt.

The table highlights the importance of incorporating local and diverse food items5 into the diet.

People need to consume diverse food items to take advantage of the different nutritional benefits associated with them. Locally available food is an accessible and cost-effective option that results in better nutritional output without changing the dietary habits of the community. For instance, replacing rice with wheat flatbread (roti), potato with egg, and adding millet to the diet can contribute 404 kcal of extra energy. It also amounts to 18 g of extra protein, two times the fat, 412 mg additional calcium, 10 g of extra iron, 152 mg of additional magnesium, 5 mg of extra zinc, and 51 µg of additional folic acid. The outcomes would certainly be substantial if these changes are adopted regularly at the household level.

The existing PDS system is largely responsible for the lack of dietary diversity. PDS contributes to approximately 40%6 of the food grain7 consumed by an average beneficiary. MSC recommends that both the central and state governments should come together to implement policy-level changes to rectify the problem of inadequate dietary diversity. It is necessary to look beyond hunger and focus on nutrition as well. Existing channels that have a wide outreach, such as PDS, Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS), and the Mid-day Meal (MDM) initiative should be utilized to promote diversity in diets. The government should consider including local food items like millets, pulses, among others, in the PDS food basket as they cost less and have better nutritional components.

The availability and affordability of food items are the primary considerations that govern dietary choices. State governments should draw inspiration from the Government of Andhra Pradesh and a few other states that offer a range of food items in their PDS baskets. However, this will only take care of supply-side issues. Nutritional literacy8 is therefore essential to ensure the uptake of diverse food items in the PDS basket. The government should play a key role to enhance nutritional literacy by designing awareness and behavioral “nudge” campaigns to ensure an understanding of dietary diversity. We have examined the demand-side aspects of PDS in another blog in this series.

The intake of proper nutrition is essential for good health. A healthy person is more productive, makes fewer visits to the doctor, and relies less on supplements in their diet. Proper nutrition and dietary diversity produce cascading effects—a woman with a nutritious diet is more likely to give birth to a healthy baby, which paves the way to a healthy childhood. Similarly, a family with a well-rounded diet is more likely to be fit for work, happy, prosperous, and would save considerable amounts of money over time on healthcare costs.

Dietary diversification is a straightforward concept—consume a variety of food items to ensure the proper intake of various macro and micronutrients, which would result in a healthy life9. A wholesome diet need not be an expensive proposition or a luxury. Diversity can be incorporated through locally available options and eating traditional dishes. Even small changes in daily food choices can improve nutritional intake, at little or no additional cost.

References:

- Guidelines for measuring household and individual dietary diversity, FAO, 2013

- PDS covers more than 800 million people across India.

- Heavy work is intense manual work and sports activities—hand tilling the land, wood cutting, carrying heavy loads, running, and jogging, among others. The prescribed nutritional intake for adults depends on the nature of work conducted.

- Dietary diversity is defined as the number of different foods or food groups consumed over a given reference period

- Why we need to eat well?, FAO, 2004

- 40% is the contribution of PDS grains to an average beneficiary’s actual monthly grain consumption

- Grains are the base for all meals in India and the term food grains includes rice, wheat, pulses, millets

- Nutrition literacy may be defined as the degree to which people have the capacity to obtain, process, and understand basic nutrition information

- Dietary diversity is associated with child nutritional status: Oxford academic, 2004

Full, yet undernourished? How India can move from food security to nutrition security

India has been a food-sufficient country for more than 30 years – but it hasn’t always been that way. Though the nation now produces enough food for its entire population, recurring famines plagued it for decades. In response, the government strengthened the distribution system to prevent the large-scale loss of lives from starvation. Controlled and systematic distribution of food grains began in India under British rule during the Second World War. Then, after the country gained independence, the government modified the system of distributing essential food grains—known as the Public Distribution System (PDS)—multiple times to address the challenges associated with food security: targeting, procurement, storage and the transportation of grains to different parts of the country.

Presently, the National Food Security Act (NFSA) governs the PDS, guaranteeing supplementary food grains to 50% of urban households and 75% of rural households in India, and reaching almost 800 million people. Under NFSA, the PDS has considerably improved people’s access to food grains by covering a substantial part of the food grain requirement for most marginalized households. However, improving access to food is not the same as ensuring optimal nutrition.

The enhanced global focus on food and nutrition security

There’s a growing recognition of this reality in the development sector. Globally, modern approaches to food security are measured based on nutrition outcomes – not simply access to food. The objective of such programs is to ensure adequate nutrition for every individual using an overall ecosystem-based approach. For instance, the UN’s Zero Hunger Challenge program works to ensure that every person can enjoy their right to adequate food, while empowering women, prioritizing family farming, and helping food systems everywhere to become sustainable and resilient.

Countries such as the United States have also adopted such holistic approaches to food security, through its Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program. Similarly, the Food Assistance for Refugees program administered by the World Food Program focuses on health, food and also nutrition. At a larger scale, initiatives such as the Global Hunger Index focus on food security, nutrition and health indicators, measuring and tracking hunger at the global, regional and national levels.

The impact of poor nutrition in India

India has yet to fully embrace this focus on nutrition. Over the past few decades, programs such as PDS, Mid-Day-Meal (MDM) and Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS) have evolved and improved in various ways. However, these efforts do not seem to have affected India’s nutrition indicators positively. An undernourished population affects the economic growth of the nation, resulting in productivity loss and otherwise avoidable health care costs. The World Bank estimates that India loses over US $12 billion annually in GDP from vitamin and mineral deficiencies.

But the impact of poor nutrition goes far beyond productivity numbers. The recently published Comprehensive National Nutrition Survey (2016-18) highlights that 35% of Indian children under five years of age, and 22% of children between five to nine years of age suffer from stunting. Additionally, the report found that 33% of children under five, and 10% of children between five and nine were underweight. Even among adolescents between 10 to 19 years of age, 24% were found to be thin for their age. These statistics are further supported by the National Family Health Survey report of 2015-16. With long-running programs like the PDS working to improve marginalized people’s access to food grains, why are these nutrition issues so persistent?

Identifying the gaps in India’s nutrition programs

MSC has been seeking an answer to that question. An MSC study concluded in August, 2019 assessed the nutrition gap in households that receive support from the PDS. This study found that on average, PDS grains contribute to approximately 40% of an average beneficiary’s actual monthly food grain consumption at the household level. (The term “food grains” in this context includes rice, wheat, pulses and millets – grains which form the basis for all meals in India.)

The study also found that most beneficiary segments – comprising men, women, pregnant women, lactating mothers and children – had low levels of basic macro and micronutrients, including protein, fat, calcium, iron and folic acid. Clearly, the operational changes to targeting and outreach in PDS over the years have not led to significant improvements in the nutrition intake of beneficiaries. Similarly, the MDM and ICDS programs’ contribution towards nutrition intake of pregnant women, lactating mothers and children were not found to be optimal.

One of the obvious and primary reasons for undernourishment is a lack of dietary diversity. Ironically, PDS, which primarily supplies rice or wheat (or both) seems to be partially responsible for instilling dietary habits that lack in diversity: It sets the norms, and the staples it distributes are often exactly the same grains that beneficiary households already grow on their farms and consume from. Further, current PDS practices are so deeply entrenched in the beneficiaries’ psyches, that they are reluctant to accept modifications to the food baskets the program provides. For example, the government of the state of Andhra Pradesh implemented a laudable initiative and expanded its PDS food entitlements to include finger millet powder (a good source of energy, protein, vitamins and minerals), pigeon peas, and groundnuts. But MSC’s research revealed that most beneficiaries avoided these grains and consumed the food baskets’ rice exclusively.

How can India shift from food security to nutrition security?

In light of our findings, it’s clear that along with food modifications, nutrition literacy must be part of interventions that aspire to improve nutrition statistics. Studies from other countries that examine large-scale nutrition outcomes show that food choice and eating habits are influenced by a wide variety of factors, such as socioeconomic status, demography, ethnicity, convenience, advertising and even biological triggers. Additionally, the potential to incur lower health care costs has also been shown to influence food choices.

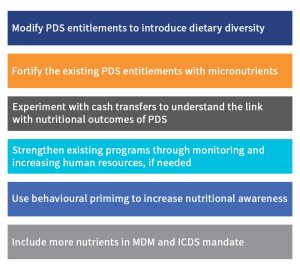

Considering these influences – along with the on-the-ground realities that enable access and encourage a willingness to choose more nutritious foods – MSC believes that a holistic strategy will facilitate the shift from food security to nutrition security. Practitioners should incorporate modifications to the existing programs and facilitate “nudges” to influence beneficiary behavior through positive reinforcement and indirect suggestions. We recommend the following ideas for practitioners to use in combination:

Let’s look at these ideas in more detail:

- PDS food baskets should include more dietary diversity, featuring local millets such as ragi and jowar, which are cheaper than wheat or rice. The program could then use the money saved to provide subsidized lentils to beneficiaries. This variety of food would ensure adequate dietary diversity among recipients. These interventions should accompany nutrition literacy initiatives to ensure uptake and penetration among the target population.

- Among our recommendations, the least expensive and easiest to implement initiative is food fortification, which should be carried out using WHO guidelines to inform the appropriate selection of safe fortification levels and modes of delivery.

- Many studies indicate that giving beneficiaries choice – e.g.: by transferring cash to recipients, so they can buy food items of their choice and preferred quality – improves the nutritional outcomes of food security schemes. Existing cash transfer schemes in India’s union territories should be further analyzed so that the model can be improved and replicated in other parts of the country. The cash coupon model (in which a combination of cash and food coupons allow beneficiaries to buy particular food items within the cash limit) should also be further tested to determine its viability at the national

- Existing programs such as Poshan Abhiyaan, Anemia Mukt Bharat, and Village Health Sanitation and Nutrition Committee are all designed with great objectives. But various reports highlight their implementation challenges. There is a need to increase ground level monitoring and training under these schemes to ensure better implementation.

- India should utilize behavioral science-based approaches that focus on local communities taking greater ownership (i.e.: embracing long-term sustainable changes that become a habit over time – unlike interventions that deliver either one-time or short-term benefits). The goal of these approaches would be to develop practical and workable solutions to help program beneficiaries adopt good nutrition practices. Together with nutrition literacy drives, these types of interventions would help solve demand-side issues that hamper good nutrition practices.

- The inclusion of additional micronutrients in existing nutrition-focused programs, such as the MDM and ICDS, is required to increase nutritional output. Additionally, supply chain oversight and data management should be more robust. Integrating technology into the delivery system of these schemes will help improve efficiency and efficacy.

What role can the private sector play?

The recommendations above open several opportunities for engagement with the private sector. Public-private partnerships can play a big role in the transition towards nutrition security, by bringing together experts, institutions and organizations that can help the government implement various nutrition-focused programs in different ways. These collaborations can focus on:

- Strategy: Private sector entities can be involved in designing the strategy and roadmap for new public initiatives. This could include various components, like research, advocacy, impact assessments, etc.

- Implementation support partnerships: Private sector players can provide support to the government as it rolls out the program at a large scale – as is the case with many other large public safety net programs run by the government. These support functions could include monitoring, evaluation and assessments.

- Supply chain and procurement: There could be additional possibilities for engaging with the private sector to procure micronutrients and manage the fortification process. Without many changes in terms of channel and logistics, fortified food could easily replace the food items provided under existing programs such as PDS, MDM and ICDS.

- Nutrition literacy: This has been one of the major drivers of persistent malnutrition levels in the country. We need to look for alternatives to ineffective approaches, and private sector players could provide new options for expanding nutrition literacy among the populace.

India’s economic growth projections are predicated on the assumption that, as a young country, its economy is likely to continue its rapid growth. But India will be hard-pressed to realize such growth if its population lacks appropriate nutrients and energy, and cannot contribute fully to society. That’s why it is imperative that the country optimize its food policy going forward. The above recommendations can guide the design of the government’s food programs, so that India may begin the slow march from food security to nutrition security.

The blog was first published on Next Billion on 29th January 2020

A study to assess the nutritional gaps in Public Distribution System (PDS) beneficiary households

India’s Public Distribution System (PDS) is the largest food security program in the world that guarantees subsidized food grains to almost 800 million people.

MSC’s report examines the PDS food basket and the dietary intake of beneficiary households to quantify nutritional gaps at the household level and to increase the nutritional efficiency of the PDS. We also provided recommendations to increase the overall nutritional output of various government programs like Mid-Day Meal and ICDS.