As of December 2024, India boasted more than 73,000 startups with at least one female director. However, the picture is bleak when it comes to India’s unicorns—only 15% have at least one female founder. This gender gap in leadership is more evident in sunrise sectors, such as climate tech, where female startup owners comprise just 39%, against a national sector-agnostic average of 48%.

At MSC, we have a rich history of supporting the acceleration and incubation of entrepreneurs who work toward financial and digital inclusion. This time, we designed WEP-उन्नति (Unnati)—a collaborative program by MSC, the NITI Aayog’s Women Entrepreneurship Platform (WEP), and the Small Industries Development Bank of India (SIDBI). WEP-उन्नति (Unnati) is dedicated to accelerating the entrepreneurial journey of women who create solutions for a greener planet.

As part of its inaugural cohort in February 2024, WEP-उन्नति (Unnati) called for applications across India and selected 15 women “greenpreneurs.” They represented 12 Indian cities and 11 industries, which include renewable energy, agro-waste management, climate-smart animal husbandry, sustainable fashion, and eco-tourism, among others. We provided them a continuum of support to address six ecosystem needs recognized by MSC and WEP’s research as essential for the growth of women-owned businesses.

In this piece, MSC offers up several “cheat codes” for entrepreneurship support organizations (ESOs) looking to dip their toes in empowering women-led climate startups.

What did WEP-उन्नति (Unnati) teach us?

Cheat code #1: Mentorship guarantees the best results—if done right

Our research reveals that only one in every four Indian women entrepreneurs can access entrepreneurial mentorship. Existing mentorship support lacks targeted goal setting and periodic monitoring, yet fails to set a fixed number of sessions to maintain structure. This dearth of clarity and regular check-ins often results in disengaged mentors and mentees who coast. Yet the biggest misstep is failing to adapt as strong programs evolve only by learning from the cohort’s feedback and refining their experience continuously. Providing a four-month-long, one-on-one mentorship then became an evidence-informed choice for us—one designed thoughtfully to avoid these common pitfalls.

“My engagement with a WEP-उन्नति (Unnati) mentor who helped me precisely where I needed was the best thing to happen to my business”, shared Vandita, whose flagship product is a nutrient-rich, chemical-free growing medium made from tender coconut waste.

We invited each entrepreneur to share the top three growth-related challenges. We then carefully matched all 15 founders with 12 industry experts (handpicked from a pool of 100+ experts) who could guide them to resolve these specific challenges. Together, our mentors brought 250+ years of industry and 100+ years of mentoring experience. They collectively have guided 12,000+ entrepreneurs, 56% of whom were women. We facilitated meetings and followed up with the mentors and the mentees for feedback and course correction—a practice that helped make the engagement more meaningful.

Our mentors triggered a shift towards profitability for 80% of the cohort. Saloni Godbole, a producer of nutraceuticals for livestock, notes, “I came to WEP-उन्नति (Unnati) as a scientist but am leaving here as an entrepreneur.” Her cattle clients were the only ones who survived a statewide epidemic in Maharashtra.

We had two key takeaways from this experience for those of you who want to empower entrepreneurs. One, look for industry experts who match the entrepreneur’s most pressing needs and are sensitive to working with someone at that stage of business. And two, spend time setting the table right so the mentors and mentees know exactly what to expect from each other.

Arundhati Kumar, sustainable fashion mentor, said, “This has been one of the best program-managed accelerators I have been part of, both as a mentor and a participant. Thank you for the rigor you brought to the process. It has helped the mentees and mentors stay accountable and committed.”

Cheat code #2: Networking improves confidence, but most entrepreneurs’ networks are poor.

Our cohort gained direct benefits from networking, such as discussions with industry leaders, soft commitments from financiers, connections with government officers, and trust in civil society. However, since this skill does not come naturally, we made an intentional effort through networking mixers, training sessions, and meetings with important public, private, and civil society stakeholders.

As an outcome of WEP-उन्नति (Unnati) introductions, Vanita Prasad, who had enjoyed the first-mover advantage with her cocktail of wastewater treating microbes, went on to build great advocacy for her industry niche in India and abroad. She connected with relevant public and private sector stakeholders, spoke at roundtables in state capitals and remote areas, and demonstrated her solution’s efficacy in front of industry giants, such as Reliance Industries.

Our research finds that women entrepreneurs in suburban and rural markets need greater networking opportunities than their male counterparts. A couple of WEP-उन्नति (Unnati) entrepreneurs also came from Tier 2 towns and echoed our findings. In the case of Pooja, these networking opportunities permitted her to export her offerings. Meanwhile, for Neha, it led to the birth of an eco-village.

The networking sessions improved confidence and risk-taking abilities in 100% of cohort participants. The WEP-उन्नति (Unnati) brand also unlocked positions in many other accelerators for the cohort, such as IIM-Bangalore’s NSRCEL.

Cheat code #3: Striking the correct balance between domain-specific and general entrepreneurial skills training

Our cohort, which includes biotechnologists, chemists, and teachers, had sector expertise but lacked foundational business knowledge. For Pooja, learning to build resilience to climate-induced risks that doom her mushroom supply chain was as crucial as learning to brand, market, and deliver elevator pitches to investors. But for artisanal products retailer Aastha Ratan, only learning to brand, market, and pitch was key. This is why we had laid out our basket of 21 intensive group sessions, which amounted to 600 person-hours, with some that built climate expertise and others that focused on legal, compliance, go-to-market strategy, alongside psychosocial challenges, among other aspects. We also ensured each trainer who was onboarded onto WEP-उन्नति (Unnati) was available to discuss the cohort’s unique business challenges one-on-one.

What were our big wins?

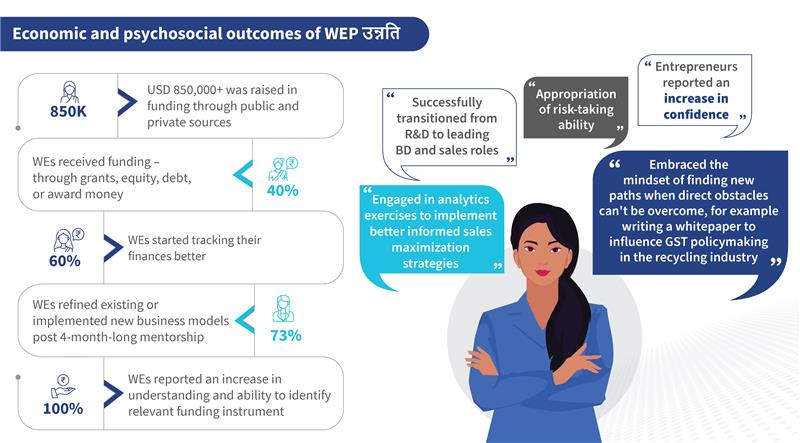

When we started working with the cohort, we found them short of practical revenue models, such as bookkeeping hygiene, sales trackers, financial projections, and legal requirements that would have made them financeable. Therefore, our training sought to strengthen the cohort’s credit and investment readiness, which led to impressive results. By the time we finished, six out of 15 women “greenpreneurs” had secured funding.

Such was the case of Renu Tupsamudre’s pitch for a cleaning agent to wash containers for reuse, which raised INR 50,00,000 in seed funding and bagged her the WEP-उन्नति (Unnati) “Greenpreneur of the Year” title. Meanwhile, Victoria D’Souza’s recycling business raised INR 35,00,000.

Even those who could not raise funds showed they were on the right track. Prerna’s ecotourism aggregator platform achieved her highest turnover to date, while Vanita saw a 50% increase in quarterly revenues. Shilpi’s sustainable clothing company achieved its annual turnover target in just five months, and 100% of the cohort could decide which funding instrument was, or would be, best for their business. This was made possible by triggering a shift from prioritizing social and environmental impact (a global behavior that has a greater incidence in women than men) to balancing it with economic gains.

The graphic below shows a snapshot of the programmatic (economic and psychosocial) outcomes of WEP-उन्नति (Unnati):

Lessons from WEP-उन्नति (Unnati) highlighted that high-growth women entrepreneurs, especially in niche areas, such as emissions reduction, circularity, and renewable energy, need support curated across key needs of domain-specific training, finance, market linkages, networking, mentorship, and compliance. This support must be sequential and fit for purpose based on their entrepreneurial stage, appetite for risk, growth, and expansion, as well as industry trends.

Today, more than 50% of the cohort successfully mobilized funds upward of INR 7.5 crores (USD 850,000). With this among other achievements, the WEP-उन्नति (Unnati) program has established strong proof of concept that such ecosystem-enabling entrepreneurship programs are effective and work well to serve the clients in desperate need of capital. Through WEP-उन्नति (Unnati), women can now give flight to their wings and build a brighter future for themselves, their families, and their community.