Everyone claims “thought-leadership and impact,” so I sympathize as you roll your eyes. But give me a few minutes of your precious time to “explain my claim.”

Twenty five years ago, MicroSave-Africa was established to help African microcredit providers diversify their mono-offerings to include savings products. The clue was in the brand. However, in 1998, East African microcredit organizations suffered primarily from enormous client churn. This was because their products were unsuitable and expensive for their target market. MicroSave’s mission quickly changed to helping financial service providers understand and address the low-income market.

Catalyzing a market-led approach for the industry

Initially, we focused on the demand side and tailored the approach I had used in Asia—participatory rapid appraisal tools set in focus groups—to derive deep insights into the needs, aspirations, perceptions, and behaviors of poor people. We codified this into the acclaimed “Market Research for MicroFinance” toolkit, which was later used by hundreds of MFIs and consultants worldwide. Indeed, a competitor design company described it as “the grandfather of human-centered design.” To this day, I am not sure if that was a compliment or a slight!

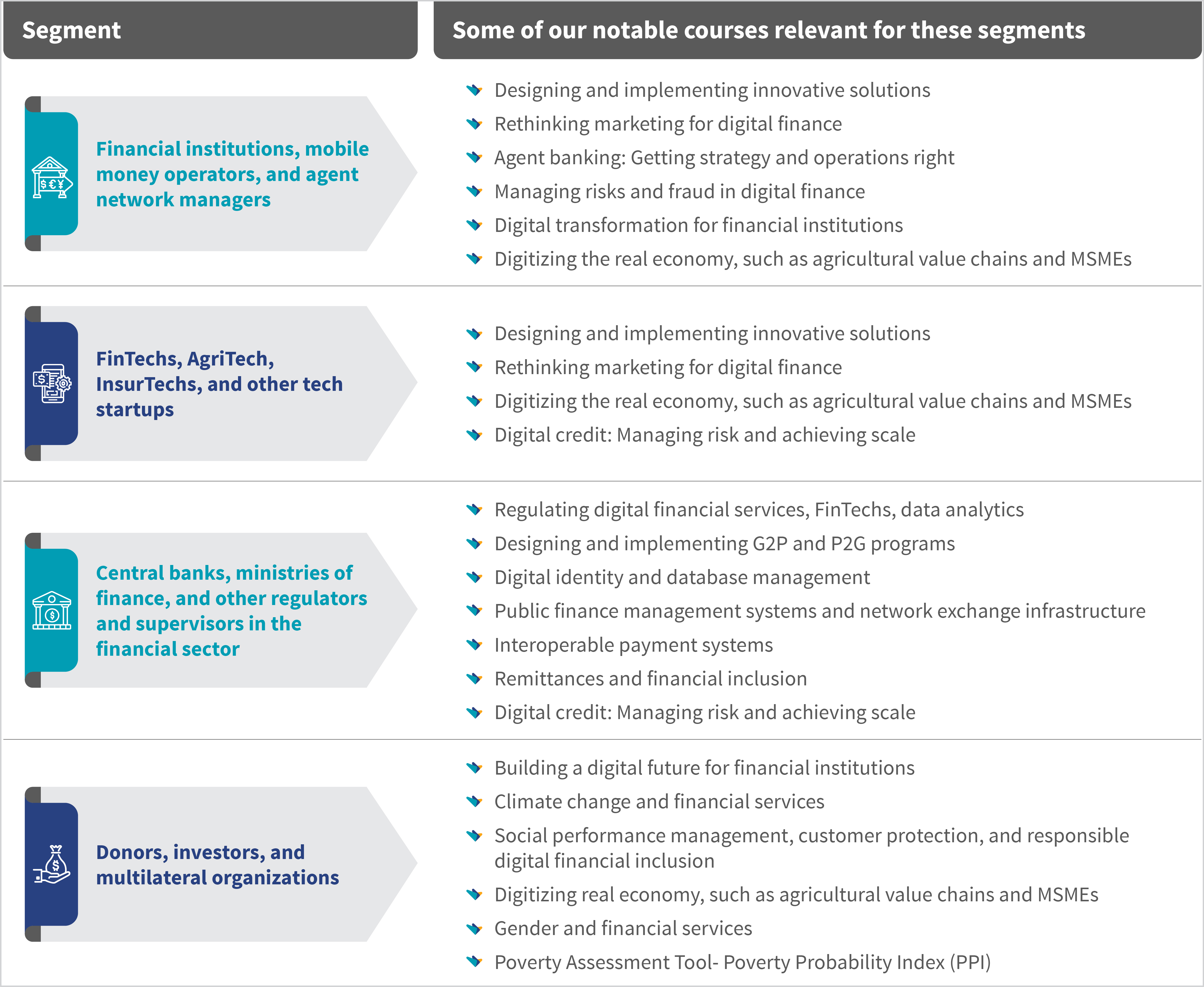

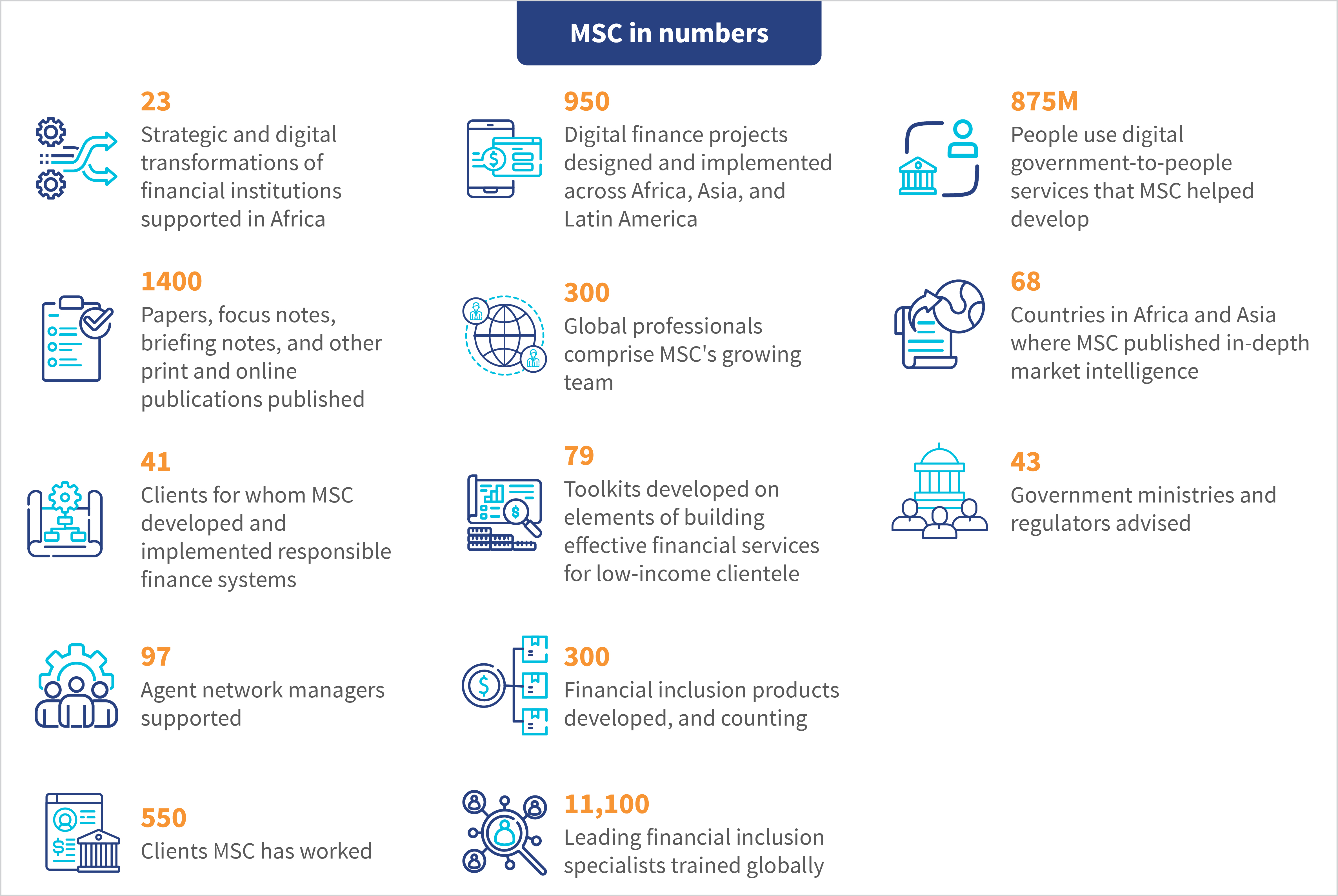

But of course, addressing the demand side alone is not enough. We needed to reengineer the supply side as well to be truly client-responsive. We collaborated with leading experts to build, test, and disseminate a range of toolkits on almost every aspect of a market-led organization. This included strategic business planning, process analysis, product marketing, and staff incentives. These toolkits are updated continuously to reflect the rapidly evolving market. They remain a core part of MSC’s internal and external training programs through what is now The Helix Institute at MSC (see table below).

Equity Bank and digital transformation

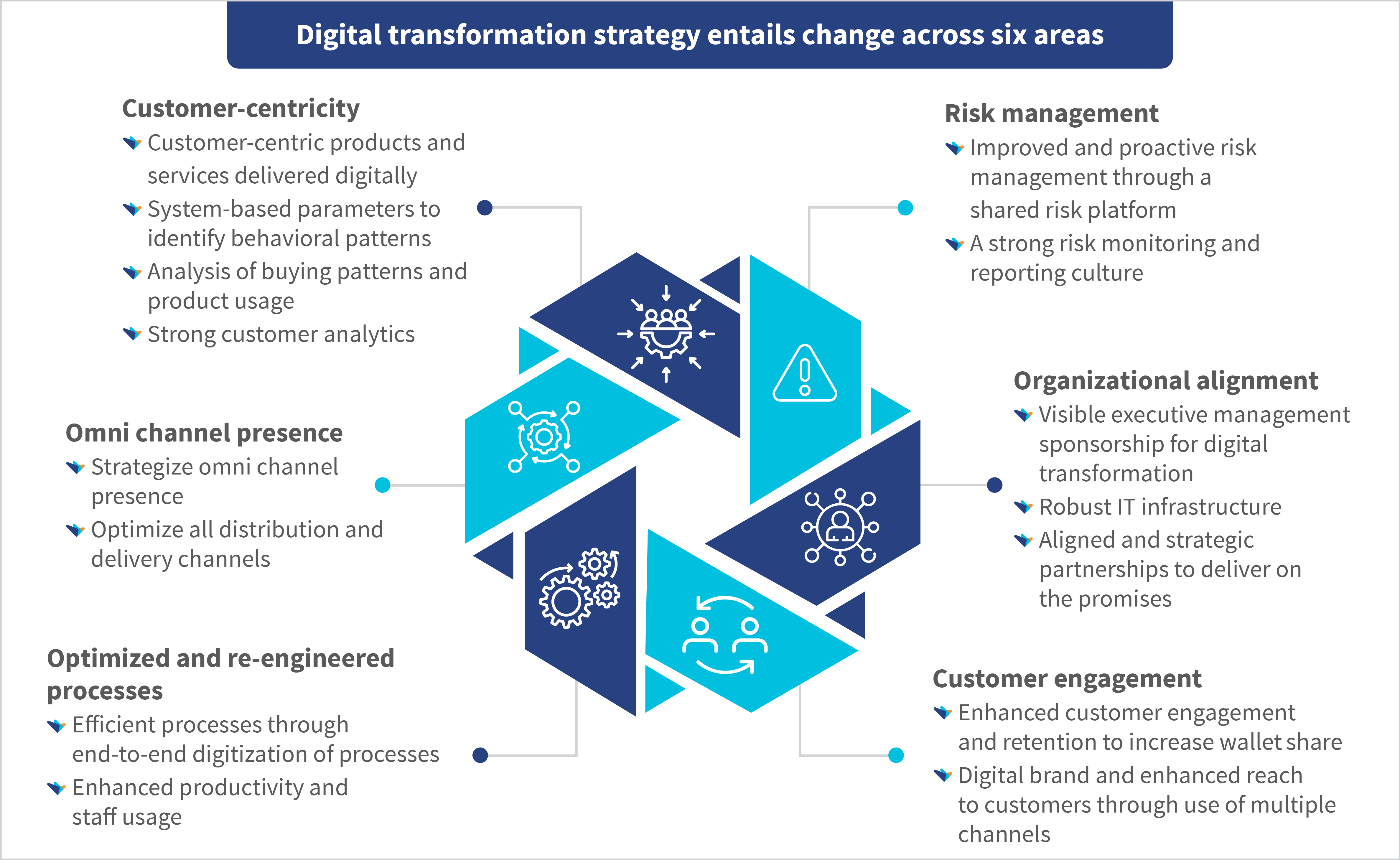

Equity Bank emerged as the poster child for MicroSave’s work to transform institutions—first on a market-led basis and then to be digitally led. When Equity Building Society first approached us in 2001, it had 109,000 customers. Today, it serves more than 15 million people in six countries, and 99% of its transactions in Kenya occur outside its branches. It was and continues to be a real privilege to work with Equity Bank and learn alongside it. The bank remains an inspiring beacon of how formal financial institutions can profitably serve the low- and moderate-income mass market if they use the digital revolution’s potential. Indeed, the lessons we learned working with Equity Bank form the basis for our extensive digital transformation practice. You can access a free introductory webinar on digital transformation here.

Therefore, it was perhaps reasonable that FSD-Kenya and CGAP’s final evaluation of the MicroSave-Africa project concluded: “MicroSave has made an undisputed contribution to the availability of better financial services for poor people across the globe. It has been good value for money, producing a wealth of outputs within the region and beyond.”

The acceleration and optimization of agent networks

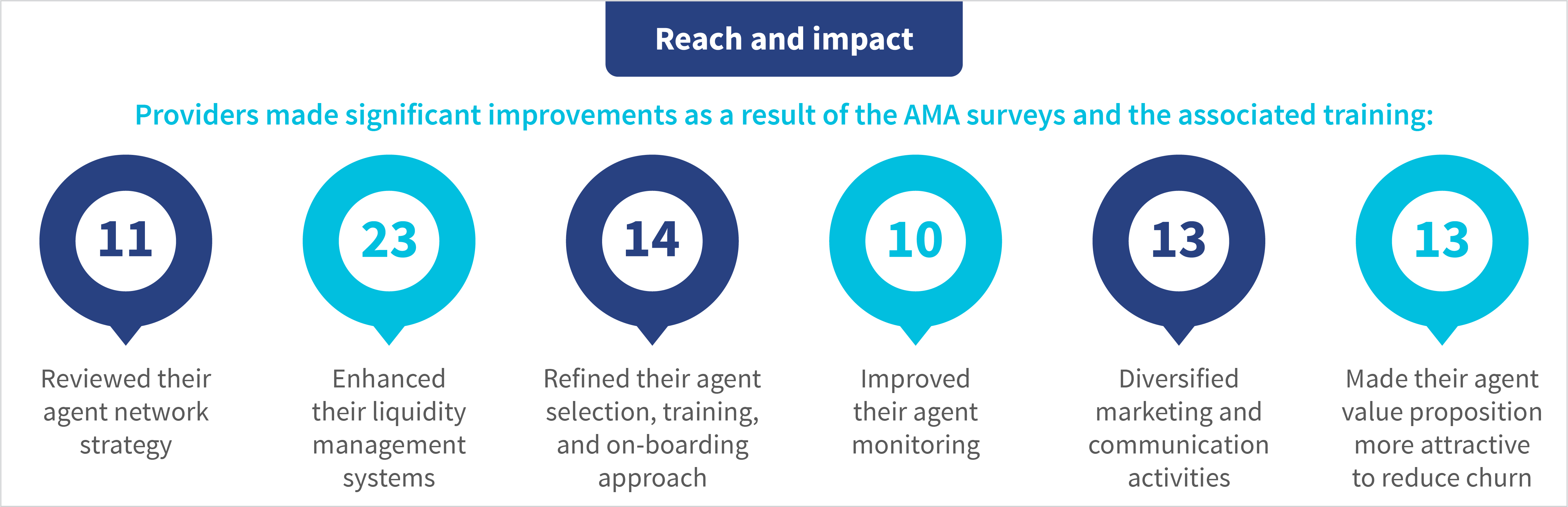

The creation or use of effective agent networks is a key part of digital transformation. MSC has worked with and trained leading mobile network operators, banks, and third-party agent network managers. These efforts have been groundbreaking.

It all started with M-PESA. MSC sat on the initial Steering Committee and conducted preliminary customer research as part of the pilot testing. It highlighted the importance of agent support and monitoring.

We built on this to design and implement the Agent Network Accelerator (ANA) program, which surveyed 31,500 agents to analyze 81 providers in 14 countries. More recently, we have worked for GSMA to look at next-generation agents. We worked with CGAP to compare, contrast, and learn lessons from five very different markets. We worked with BCG to deepen our understanding of the economics of agent networks in Indonesia. Additionally, we worked with CGAP/DFI’s agent networks course. See here to enroll .

We built on this to design and implement the Agent Network Accelerator (ANA) program, which surveyed 31,500 agents to analyze 81 providers in 14 countries. More recently, we have worked for GSMA to look at next-generation agents. We worked with CGAP to compare, contrast, and learn lessons from five very different markets. We worked with BCG to deepen our understanding of the economics of agent networks in Indonesia. Additionally, we worked with CGAP/DFI’s agent networks course. See here to enroll .

Enhancing policy and digital governance

MSC collaborates with governments on public policy in various areas, such as food security, agriculture, health, energy, and financial inclusion. We have partnered with various countries to develop, evaluate, and implement vital digital public infrastructure and the programs they support. These countries include Bangladesh, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Malawi, and Zambia. Our efforts focused on the foundational infrastructure and the development and rollout of government-to-person (G2P) programs.

Driving policy and impact at real scale

1. Malawi and Zambia: We conducted digital readiness assessments and formulated detailed roadmaps for the countries’ transition to digital G2P payments.

2. India:

- We contributed to PAHAL and Ujjwala LPG (cooking gas) initiatives. Our efforts helped eliminate 33 million fraudulent beneficiaries from the system;

- We reviewed the National Food Security Act (NFSA) and provided recommendations to enhance nutritional outcomes for 800 million people;

- Our guidance to reshape the Pradhan Mantri Jan Dhan Yojana (PMJDY) helped open nearly 500 million bank accounts with an average balance of USD 51;

- We recommended reforms for the direct benefit transfer (DBT) in fertilizer distribution, which has since benefited 118 million farmers.

3. Indonesia:

- We offered crucial insights for the Bantuan Pangan Non-Tunai (BPNT) food subsidy transfer program. It had 5 million beneficiaries in 2018, which has now increased to 20 million beneficiaries. It has been renamed to the Sembako program.

- Our advisory role led to the formation of a strategy for the electronic know-your-customer (e-KYC) process. The strategy is expected to benefit 60 million unbanked individuals in Indonesia.

MSC uses deep market insights derived from our human-centered design and process analysis toolkits to devise innovative solutions, conduct preliminary tests, and solve complex challenges. We also provide monitoring and evaluation services that enable our clients to optimize their systems and operations.

Driving and scaling innovation

MSC’s leadership on digital inclusion, it is unsurprising that we have been involved as technical service providers to labs or accelerator programs in Bangladesh, India, Senegal, and Vietnam. These labs are differentiated by their resolute focus on nurturing startups. They have a clear and consistent commitment to serve the low- and moderate-income (LMI) segments. In India, the FI Lab has supported 50+ startups that have positively impacted the lives of 47.7+ million LMI people and raised USD 266.5 million in funding in just five years.

A center of excellence for professional development

As with all leading consulting firms, MSC experiences staff churn of 10-20% per annum. A few staff leave because of the pace of organizational growth and change, or the pressure of our commitment to excel in all that we do is too much. Several leave for higher studies and use their time and experience with us to gain enrollment for postgraduate studies in prestigious universities—typically in the US or the UK. Some leave to use their experience with us to set up their own startups—including the remarkable FarMart and Flow. But many leave to join other organizations—most commonly UNCDF, IFC, and GSMA. You can find a library of slides and videos of our alumni as they discuss their work and how their time at MSC helped them do it here.

Initially, we found it disheartening to spend years building the knowledge, skills, and professionalism of bright young individuals, only to see them whisked away by international agencies that now largely operate as rival consulting companies with higher salary structures. We are a little more sanguine now. We have to view MSC as a respected and valued center of excellence for professional development with outstanding graduates who make important contributions to global development and our core mission: “To strengthen the capacity of institutions to deliver market-led, scalable financial, economic, and social inclusion in the digital age to all people.”

Explore the transformative approach that the Government of Bihar has undertaken to boost aquaculture in Bihar, through JEEViKA. This blog delves into how JEEViKA mobilizes women SHG-based fish farmer producer groups (FFPGs) and provides them with access to community ponds and water resources to take up aquaculture as a livelihood activity. This initiative has multiple gains, such as improved income and nutrition, increased access and control of women over community resources, and rejuvenation of water resources to tackle climate change. This initiative brings women to the forefront of a livelihood stream that has traditionally been a male domain.

Explore the transformative approach that the Government of Bihar has undertaken to boost aquaculture in Bihar, through JEEViKA. This blog delves into how JEEViKA mobilizes women SHG-based fish farmer producer groups (FFPGs) and provides them with access to community ponds and water resources to take up aquaculture as a livelihood activity. This initiative has multiple gains, such as improved income and nutrition, increased access and control of women over community resources, and rejuvenation of water resources to tackle climate change. This initiative brings women to the forefront of a livelihood stream that has traditionally been a male domain. UPI broke all records in August 2023. It observed 10.586 billion transactions that amounted to INR 15 trillion (~USD 189.64 billion). It has become the preferred payment choice for digitally-savvy Indians. However, it cannot reach the feature phone users. Its penetration is limited to urban segments with high usage of smartphones and mobile Internet. India is home to 400 million feature phone users. These users have limited avenues for digital transactions. They largely depend on physical access points for financial transactions. This blog discusses an innovative offline payment solution, UPI 123Pay, and its immense potential to bring digital payment convenience to the underserved segment.

UPI broke all records in August 2023. It observed 10.586 billion transactions that amounted to INR 15 trillion (~USD 189.64 billion). It has become the preferred payment choice for digitally-savvy Indians. However, it cannot reach the feature phone users. Its penetration is limited to urban segments with high usage of smartphones and mobile Internet. India is home to 400 million feature phone users. These users have limited avenues for digital transactions. They largely depend on physical access points for financial transactions. This blog discusses an innovative offline payment solution, UPI 123Pay, and its immense potential to bring digital payment convenience to the underserved segment. India’s farmers have had a long history of struggle. For decades, they have battled a multitude of agricultural challenges, such as fragmented landholding, numerous intermediaries, and low value addition. In response, the country has actively promoted farmer producer organizations (FPOs) as a solution. FPOs intend to address these serious issues through the aggregation of demand for high-quality inputs, credit, and technologies and the aggregation of outputs to improve smallholder farmers’ market access. Yet despite these efforts, major processors and output purchasing companies hesitate to engage directly with FPOs. This blog explains the options available for FPOs to trade with institutional buyers and the on-ground issues FPOs must overcome to establish better market linkages.

India’s farmers have had a long history of struggle. For decades, they have battled a multitude of agricultural challenges, such as fragmented landholding, numerous intermediaries, and low value addition. In response, the country has actively promoted farmer producer organizations (FPOs) as a solution. FPOs intend to address these serious issues through the aggregation of demand for high-quality inputs, credit, and technologies and the aggregation of outputs to improve smallholder farmers’ market access. Yet despite these efforts, major processors and output purchasing companies hesitate to engage directly with FPOs. This blog explains the options available for FPOs to trade with institutional buyers and the on-ground issues FPOs must overcome to establish better market linkages. The Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDP) of India was published in the Official Gazette on 11th August 2023, after years of deliberations. This came after the Act passed both Houses of Parliament and received Presidential approval. This blog highlights the key provisions of the DPDP Act. Please note that many significant details about the implementation of the Act will be decided later by rules set by the Central Government.

The Digital Personal Data Protection Act (DPDP) of India was published in the Official Gazette on 11th August 2023, after years of deliberations. This came after the Act passed both Houses of Parliament and received Presidential approval. This blog highlights the key provisions of the DPDP Act. Please note that many significant details about the implementation of the Act will be decided later by rules set by the Central Government.

Behind Jakarta’s bustling business district, a small hawker skillfully prepares batagor, a beloved Sundanese delicacy. Customers form a queue and use

Behind Jakarta’s bustling business district, a small hawker skillfully prepares batagor, a beloved Sundanese delicacy. Customers form a queue and use