Yuyun sells food items and products of daily use from a small shop from her home in Central Java, Indonesia. By late February, 2021, Yuyun had four outstanding loans. While four concurrent loans seem excessive, Rahmat Kabir from Hrishipara in central Bangladesh goes a step further. By the middle of 2021, Rahmat had 13 outstanding loans—seven from multiple microfinance institutions (MFIs), five from friends, and one from a neighbor.

However, juggling multiple loans is not common to all micro-enterprise owners. Only two of our diarists from India had more than two outstanding loans—most had either one loan or no loan at all. One such diarist, Manish Chouhan, runs a grocery shop in Madhya Pradesh, India. Manish was trapped in a vicious cycle—reduced stocks due to a drop in income led to lower sales and a consequent decrease in revenue. To break this cycle, Manish had to borrow INR 10,000 (~USD 134.79) from his friends to purchase supplies for his shop.

These examples illustrate the difference in borrowing patterns in the three Asian countries of our Corner Shop Diaries research—India, Indonesia, and Bangladesh. By analyzing the loan transaction data of our diarists, we identified the key insights discussed below.

1. Taking loans is more common in Bangladesh, followed by India and Indonesia

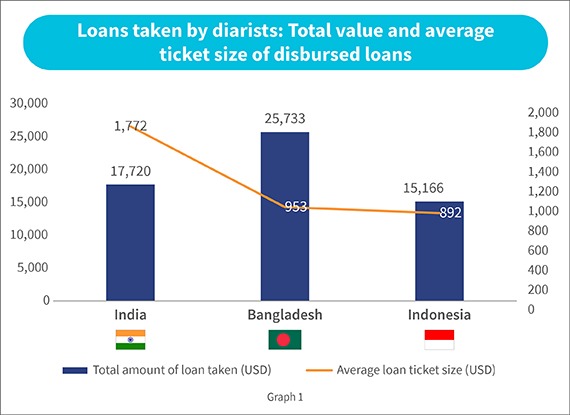

Only eight out of 25 diarists had outstanding loans in India. These diarists had a total of 10 outstanding loans. In Indonesia, 10 diarists had a total of 17 outstanding loans, while in Bangladesh, four out of five diarists had as many as 27 running loans in total. Bangladesh also tops the list in terms of total loan value disbursed, as depicted in Graph 1. The reason behind the significant difference in the number and value of loans is the phenomenal growth of MFIs in Bangladesh since the 1990s. These MFIs facilitate access to credit for the low- and moderate-income (LMI) segment in rural and urban areas.

Other possible reasons for the difference in number and value of loans across countries:

The diarists did not divulge the details of loans taken willingly. We had to gain their trust and make them comfortable enough to reveal this information. Taking loans is not a desirable practice in the cultures of some of our countries of research. This may be a significant factor responsible for this reluctance in sharing information, and the levels of reluctance also vary across countries. Another factor is the difference in skills of data collectors who acquired the sensitive information related to credit. However, we can safely assume that these are not the only factors that contribute to the significant difference in the number of loans. Borrowing behaviors may also vary based on historical and market-level aspects of the country, as mentioned before.

2. Banks and MFIs are significant sources of loans

In general, borrowers in India prefer to take loans from formal institutions- mainly banks and some NBFCs. In Indonesia, informal institutions like Rotating Savings and Credit Associations (ROSCAs) and formal institutions like banks, cooperatives, and MFI are familiar sources of loans. With the historical evolution of its microfinance industry to curb rural poverty, MFIs are the major source of credit in Bangladesh . The country has been expanding its banking industry to push economic growth—most recently through agent banking. Besides these sources, borrowers in Bangladesh also take loans from informal sources like friends and family.

These practices reflect the experiences of our diarists in these countries. Diarists in India prefer to secure loans from banks, with seven out of 10 loans taken from banks. In Indonesia, diarists took almost half of the loans (eight out of 17 or 47%) from MFIs, five from banks, and the remaining four from other sources like cooperatives and friends or relatives. Since we conducted our research in the primary working area of CU Lestari, our partner in Indonesia, several diarists have outstanding loans with the MFI.

Due to the overwhelming presence of MFIs in Bangladesh, diarists took 70% i.e. 19 out of 27 loans from MFIs. The remaining eight loans were taken from informal sources like friends and relatives. The abundance of access is a major factor that influences the choice of borrowers regarding the source of the loan. Prominent MFIs like Grameen Bank and BRAC, mid-sized MFIs like DSK, and smaller local MFIs like Sahaj Sanchay operate in Hrishipara, the area that our project covered. This made it easier for diarists to take multiple loans, either under their names or through accounts owned by people they know. Moreover, most MFIs in Bangladesh have also relaxed their terms of repayment after the pandemic.

The interest rates also vary significantly depending on the source of the loan. In India, banks charge interest rates of 7% to 13%, whereas money lenders charge interest as high as 18%. In Indonesia, the interest rates range from 2% to 24%, and in Bangladesh, they can go as high as 36% per year.

Informal loans from friends or relatives are usually interest-free and have flexible terms of repayment. Hence, these loans are the first choice for many. Informal loans are also the choice of instrument to repay other outstanding loans with stricter terms of repayment.

3. Diarists take loans primarily for business purposes

Diarists in India took more than half of the loans (six out of 10) for personal reasons and the other four to support their businesses. However, loans for business or livelihood were more predominant in Indonesia and Bangladesh—11 out of 17 (65%) loans in Indonesia and 22 out of 27 (81%) loans in Bangladesh were business loans. In Bangladesh, borrowers take business loans but often use the amount for various purposes. Borrowers generally use informal loans for a single purpose, such as to on-lend to others or repay debts, or smoothen their income. They consume such loan amounts swiftly. In contrast, borrowers use MFI loans mainly for business purposes and spend this amount slowly. They also use some parts of such loans to repay other loans or smoothen their income, among others.

Conclusion

The samples[1] from India, Indonesia, and Bangladesh highlight the difference in behavior regarding loans in South and Southeast Asia. Financial service providers can extract essential lessons from the complete picture of how and why borrowers take loans, their pain points, and the catalysts of loan adoption.

Loans are not always a burden but a stepping stone for growth, as evident in Case 1. Micro and small enterprises need access to finance to scale up and grow their business. Even small loans can have a significant impact on these enterprises. Loans help in consumptions smoothing, to build a cash reserve or to repay another loan, as highlighted in Case 2. However, mostly informal micro-enterprises still struggle with the lack of loan products tailored to their needs.

Stakeholders can learn from the example of CU Lestari—the MFI has attracted numerous LMI customers through its direct approach, such as providing a cash pick-up service for loan repayments. As businesses bounce back after the pandemic and the demand for credit rises, early movers will reap the benefit.

[1] We have not extracted the diaries data from a representative sample. Hence, the insights cannot be generalized.

A woman carries a goat to safety after a flood in rural Bangladesh. During floods and other natural disasters throughout Bangladesh’s history, MFIs have continued to serve low-income customers. Photo: Moniruzzaman Sazal, 2017 CGAP Photo Contest

A woman carries a goat to safety after a flood in rural Bangladesh. During floods and other natural disasters throughout Bangladesh’s history, MFIs have continued to serve low-income customers. Photo: Moniruzzaman Sazal, 2017 CGAP Photo Contest

ChitMonks works with chit fund companies and several different stakeholders in the chit fund industry. These stakeholders include regulators and other enablers in the chit fund ecosystem. ChitMonks started in Telangana, where it designed, developed, and implemented its product while lending support to the state government, its regulated chit fund companies, and their subscribers. It transformed the entire chit fund infrastructure from manual systems to a blockchain based system. Progressing from Telangana, ChitMonks has already started work in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. Today, it is in talks with the state governments and regulators of a few more Indian states to expand its reach.

ChitMonks works with chit fund companies and several different stakeholders in the chit fund industry. These stakeholders include regulators and other enablers in the chit fund ecosystem. ChitMonks started in Telangana, where it designed, developed, and implemented its product while lending support to the state government, its regulated chit fund companies, and their subscribers. It transformed the entire chit fund infrastructure from manual systems to a blockchain based system. Progressing from Telangana, ChitMonks has already started work in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. Today, it is in talks with the state governments and regulators of a few more Indian states to expand its reach.