Agriculture is the life of the Indian economy. However, several structural challenges, such as intermediaries throughout the value chain and limited access to technology, credit, and markets, hinder this sector from reaching its full potential. This video highlights how AgriTech start-ups under the FI lab have been shaping the agriculture sector through technology and innovation.

NXTFIN-XaasTag: Technology-enabled mainstreaming of farmers’ collectives

This blog discusses XaasTag, a start-up under the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program. Some of the largest philanthropic organizations across the world support the FI Lab, such as the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, J.P. Morgan, Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, MetLife Foundation, and the Omidyar Network.

India has 145 million Indian farmer households, of which 87% are small and marginal farmers, who own less than 2 hectares of land. Although these farmers contribute to 60% of the total production of food grains and more than half of the country’s production of fruits and vegetables—they face numerous issues across the value chain.

While agriculture supports around half of the population in India, the average monthly income of farmers in the country is only INR 6,426 (USD 87). Small and marginal farmers struggle to access good quality and affordable inputs, market linkages, and credit. This is due to the small and fragmented landholdings and the absence of an adequate institutional framework to safeguard their interests. They are unable to integrate with the broader agriculture value chains and face the risks and challenges of volatility in the prices of commodities, crop failure, and expensive credit.

The lack of market access remains one of the major issues, which compelled Shiv Kumar and Gaurav Sharma to start XaasTag as a solution to empower farmers to secure better returns.

The lightbulb moment:

Shiv Kumar, a computer science and management graduate, served in the Indian Air Force. He took voluntary retirement in 2004 and started a venture from his garage. Over the years, Shiv worked at different places and co-founded three organizations around telecom services in small-town and rural India. During his association with e-Sahaj, one of the SREI group of companies, he met Gaurav. During their time with e-Sahaj, they closely observed the plight of the farming community, especially small and marginal farmers. Initially, the absence of health insurance services for the farming community struck them the most.

This gave birth to the idea of XaasTag. Shiv and Gaurav co-founded the organization and partnered with Religare Health Insurance to create an insurance product for rural India, which also included livestock insurance. They realized that retail insurance involved huge costs after running small pilots with a select group of farmers. Instead, they opted for a group-based model for insurance, credit, or both. Hence, XaasTag decided to work with farmers’ collectives, such as the farmer producer organizations (FPOs).

After multiple iterations and tweaks to their product offerings, the team identified access to reliable markets with a predictable price for their produce as the major need of farmers. They also analyzed the demand side, mainly institutional buyers who purchase from FPOs in bulk, such as intermediaries for retailers who supply to BigBasket, a large online commerce player. These intermediaries need a regular supply of agri-produce with consistent quality and price. These analyses prompted Shiv and Gaurav to pivot their product into a marketplace to connect FPOs and buyers.

After multiple iterations and tweaks to their product offerings, the team identified access to reliable markets with a predictable price for their produce as the major need of farmers. They also analyzed the demand side, mainly institutional buyers who purchase from FPOs in bulk, such as intermediaries for retailers who supply to BigBasket, a large online commerce player. These intermediaries need a regular supply of agri-produce with consistent quality and price. These analyses prompted Shiv and Gaurav to pivot their product into a marketplace to connect FPOs and buyers.

In its current avatar, XaasTag links FPOs to institutional buyers with an overarching goal to provide farmers with assured and enhanced income through reduced price volatility and better predictability.

What makes XaasTag unique?

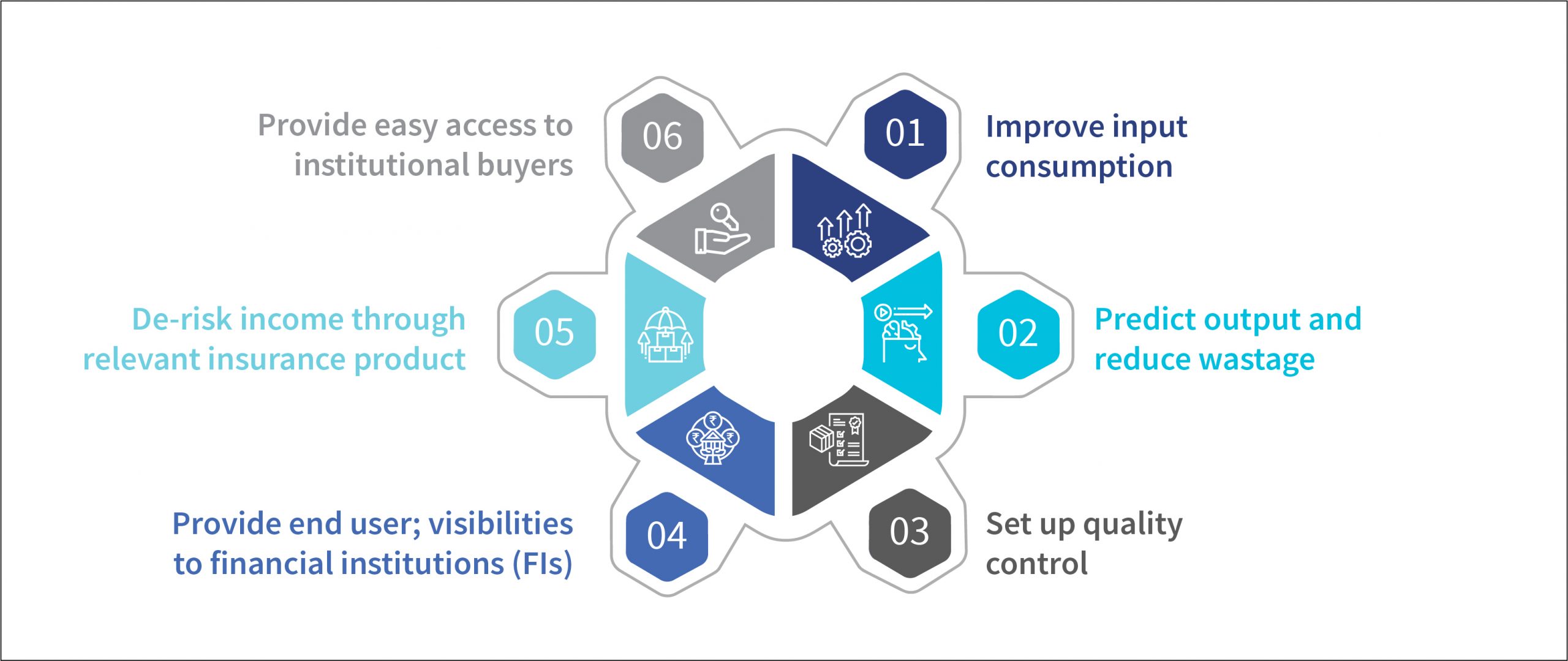

XaasTag’s NXTFIN is an online marketplace to connect FPOs on the supply side and agri small and micro enterprises (SMEs) on the demand side. NXTFIN enables agri-SMEs to work closely with farmers in providing easy access to low-cost loans and insurance services. NXTFIN hosts the following tools and services developed with its partners and affiliates:

The platform is a curated and diligently crafted marketplace. It carefully screens FPOs based on various parameters like the quality and quantity of produce. It also maps their supplies to the right buyers through the match-making algorithm XaasTag employs at the backend. The team works with farmers from planning to harvesting to the final supply of goods to institutional buyers. The team also prescribes a suitable “package of practice” for the crop, and conducts a physical verification before the goods are supplied.

Impact on LMI segments: Small and marginal farmers

The traditional process at mandis

An Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC) mandi is the traditional market where most farmers sell their produce under a spot trading system. A set of traders, also called arhatiyas, depress spot prices, armed with the knowledge that farmers have already spent enough on the transportation of their produce. Hence, farmers have to sell at suboptimal prices. Unfortunately, the government’s electronic auction system, eNAM, has not helped farmers much in the discovery of better prices.

Here comes XaasTag

XaasTag makes a direct impact on farmers in two ways, as depicted in the image below.

The roadblocks

Like any startup, XaasTag faces its share of challenges. These are focused on the following three aspects:

- FPO onboarding: Since XaasTag is new and relatively less known in the market, the team has found it challenging to convince and onboard FPOs who rely heavily on long-standing relationships to partner for the business.

- Scalability: The onboarding of FPOs is completely manual, which makes the process laborious and time-consuming.

- Retention: It lacks a value proposition for FPOs to build lifetime customer value (LTV) and strengthen their engagement with XaasTag.

Support from the FI Lab:

As part of the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program, XaasTag received assistance based on the challenges it faced, which helped them in the following ways:

- To overcome issues around scalability, the Lab helped develop an FPO onboarding assessment toolkit. XaasTag can integrate this scorecard-based FPO assessment tool with the NXTFIN platform. The scorecard accepts existing data that registered FPOs have shared over NXTFIN as input. The tool assesses multiple parameters ranging from scalability to the governance of an FPO and helps XaasTag identify promising FPOs for its platform. It provides a consistent, auditable, and objective assessment of the FPOs to help anyone in the team evaluate an FPO. With this, the team no longer needs to visit every FPO personally to assess its fitment.

- To build the value proposition for FPOs and to retain them with XaasTag, the Lab has been developing a training toolkit on business planning for FPOs. The toolkit is in the form of a digital comic book that will capture the importance of business planning, its components, and the process to build a sustainable business plan for an FPO. To build the internal capacities of FPOs, XaasTag will circulate this digital comic free of charge among its registered FPOs. This should help build trust and stickiness between the FPOs and XaasTag.

Vision for the future

XaasTag plans to partner with many more FPOs and engage more actively with farmers through a bigger team. XaasTag wants to utilize its huge database of FPOs and map the production to the right buyer. It also plans to set up production hubs. These hubs will act as small transit storage spaces for less perishable produce and a point for some level of processing, such as grading and sorting, among others, for enhanced efficiency.

This blog post is part of a series that covers promising FinTechs that make a difference to underserved communities. These start-ups receive support from the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program. The Lab is a part of CIIE.CO’s Bharat Inclusion Initiative and is co-powered by MSC. #TechForAll, #BuildingForBharat

Aggois: Creating robust liquidity for farmers

This blog charts the story of Aggois, a startup that is a part of the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program, which is supported by some of the largest philanthropic organizations across the world—Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, J.P. Morgan, Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, MetLife Foundation, and Omidyar Network.

58% of India’s households and more than 41% of the country’s labor force depends on agriculture and allied sectors as their primary source of income. However, these sectors continue to struggle. About 82% of the farmers in India are categorized as small or marginal. They struggle to find a decent price for their produce, access finance and get optimal market linkages. Aggois’ work focuses on solving one of these problems—lack of access to finance.

Learning question:

Sixty-two-year-old Kamla Bai is a marginal farmer from Kodli village in north Karnataka. Her intermittent income, which comes from agriculture, is barely enough to meet regular expenses, and savings are inadequate to take care of unforeseen expenditures, such as illnesses and other life events. So she frequently resorts to borrowing money, mainly from informal sources, to make ends meet.

She harvested her Kharif crop of pigeon peas in November, 2020. Earlier in the year, the government had announced a minimum support price (MSP) for pigeon pea at INR 60 (USD 0.82) per kg. She had the option to sell her produce under MSP procurement at the Kodli agricultural society located near her farm. However, she would have to wait for a few weeks to receive payment. Her other option was to sell her produce in the open market at INR 40 (USD 0.54) per kg and get immediate payment. Kamla Bai is in a dilemma as she always runs short on money, which she needs to pay off her debts and prepare for the next sowing season.

She harvested her Kharif crop of pigeon peas in November, 2020. Earlier in the year, the government had announced a minimum support price (MSP) for pigeon pea at INR 60 (USD 0.82) per kg. She had the option to sell her produce under MSP procurement at the Kodli agricultural society located near her farm. However, she would have to wait for a few weeks to receive payment. Her other option was to sell her produce in the open market at INR 40 (USD 0.54) per kg and get immediate payment. Kamla Bai is in a dilemma as she always runs short on money, which she needs to pay off her debts and prepare for the next sowing season.

Kamla Bai’s situation is common amongst most farmers in India. Prominent markets for farmers include Agriculture Produce Market Committees (APMCs, which are government-regulated mandis); private traders and processors; and MSP based procurement by government agencies.

The rates offered and timelines for payments vary across these channels. For example, private traders and APMCs provide farmers with timely payments, but usually at lower rates than the MSP.

While the MSP is mostly higher, the lag between procurement and payment ranges from two to eight weeks on average. Yet most farmers need some money, almost immediately, to prepare for the next crop cycle. Thus, farmers borrow from informal sources such as moneylenders or traders, at 3-6% per month, as they cannot access formal lending institutions.

What did Aggois decide to do about this?

Founded by Prathmesh Kant and Akhil Sharma in 2017, Aggois is based in the state of Karnataka and works predominantly in the Kalburgi district. Aggois consulted with multiple stakeholders in the agri ecosystem to analyze the challenges. These stakeholders included agri experts, government officials, banks, Primary Agriculture Credit Societies (PACS), and most importantly, farmers.

Founded by Prathmesh Kant and Akhil Sharma in 2017, Aggois is based in the state of Karnataka and works predominantly in the Kalburgi district. Aggois consulted with multiple stakeholders in the agri ecosystem to analyze the challenges. These stakeholders included agri experts, government officials, banks, Primary Agriculture Credit Societies (PACS), and most importantly, farmers.

Turn-around-time (TAT) between the sale of produce and receipt of payments, typically for MSP procurements, was a major pain-point for farmers. Aggois fills this gap by providing farmers with financing support during this period. The government does large-scale MSP procurement for various crops. This, therefore, presents a huge market opportunity for Aggois.

What does Aggois offer to farmers?

Aggois provides farmers with short-term credit in proportion to the sale value of their produce under MSP procurement. The startup captures personal details of the farmers and details of the produce sold on the platform to set up farmers’ profile. After the sale of produce at the MSP, the loan amount is disbursed in the farmer’s bank account. Aggois recovers repayments automatically from the farmer’s bank account through NACH mandates once a farmer receives payment from procurement agencies.

What makes Aggois unique?

Aggois differentiates itself from other credit providers in multiple ways:

- Most financiers provide credit through farmer aggregations as a B2B service. In contrast, Aggois provides credit directly to farmers and therefore works as a B2C service.

- The PACS that undertake MSP procurements act as partners for customer acquisition and facilitation of the process. In the future, Aggois intends to partner with Farmer Producer Organizations (FPOs) as well.

- The process of disbursal and repayment that Aggois offers is relatively hassle-free compared to the cumbersome processes required by many financial institutions. Aggois disburses the loan directly into the bank accounts of farmers and automatically recovers from the same account through technology integration and payment instruments. This mitigates the credit risk for Aggois, without a workforce for collections.

- Through its solution, Aggois connects directly with farmers and introduces them to formal finance. Once this channel with the farmers is established, other financial institutions will have the option to offer different products to farmers who have digital footprints.

How does Aggois make the lives of farmers better?

Let us look at how Kamla Bai’s life transformed to understand the impact of Aggois’ initiatives.

Before taking the final decision between receiving immediate payments or selling at MSP, Kamla Bai visited the Kodli society, which introduced her to the Aggois team. It explained to her the value proposition of associating with the startup.

Kamla Bai decided to sell her produce at Kodli society at MSP. Against the MSP of INR 60,000 (USD 820) per quintal, she got a short-term credit of INR 37,000 (USD 500) from Aggois. She was able to pay-off all her current debts and prepare for the next sowing season using this credit. She received her payment after around three weeks. With her consent already taken at sign-up, Aggois deducted the loan amount from her account digitally.

Aggois’ path to success is challenging

As Aggois started operations, the major roadblock it faced was the lack of farmers’ trust of a privately owned business that was largely unknown in their region. The team collaborated with PACS to overcome this issue. PACS have been around for decades and almost every farmer is a member. These organizations provide farmers with services including credit, agri-inputs, and marketing.

Despite overcoming the trust deficit by collaborating with PACS, Aggois faces other significant challenges:

- It struggles to ensure a steady line of credit from financial institutions at viable rates of interest.

- The TAT for the loan disbursals is prolonged by the paper-based NACH system, which takes about 10-12 working days for the approval and disbursal of loans. With a short window of opportunity spanning 45-50 days, this time lag is quite significant. This lowers the value proposition of Aggois’ solution for the farmers.

- The onboarding of farmers is completely manual, which makes the process laborious and time-consuming.

- Currently, due to its small team size, and restricted mobility due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Aggois operates in a limited geography and focuses on a handful of crops that the MSP covers. Hence, it is unable to conduct continuous operations all year round, thereby inhibiting the optimal utilization of its staff.

Aggois can expand its customer base rapidly, if it is able to address these issues and move forward.

How has the FI Lab supported Aggois so far?

The FI Lab supported the startup to develop a business continuity plan. After widespread stakeholder consultation, the Lab assessed the business model from a strategic and operational perspective. It studied numerous financing gaps along the value chain and considered the potential of the respective actors to identify opportunities for intervention.

Partnerships are important for the streamlined functioning of business and hence the Lab has been assisting Aggois to find the right set of partners to take its business to scale.

The Lab has also analyzed and recommended potential geographies and crops for Aggois to scale up its business in the near term. It recommended Aggois an optimal organizational structure to fulfil its current business needs. The lab looked at operational aspects and suggested improvements to enhance efficiency and effectiveness.

The lab also helped Aggois to capture the nuances that apply to UI/UX (user interface /user experience) while designing a farmer-facing mobile app. The app will help digitize the entire process right from onboarding to the financing of farmers and achieve scalability.

With this, the team no longer needs to visit every farmer personally to onboard and they can easily scale to many geographies in time to come.

The future is bright

The past few months have been hard work for Aggois’ team. It had to build the technology platform and develop a healthy rapport with the target PACS. Having delivered results for its initial set of farmers, Aggois now rides on network effects for expansion—as the beneficiary farmers have started recommending it to their peers.

This network effect will spread the word among the larger farming community and instill confidence not only in them, but also among the lending financial institutions. This should help the Aggois team to expand its customer base geographically, as well as for multiple crops, and ensure a steady line of credit to the business from financial institutions.

In the medium to long term, Aggois intends to expand vertically by providing complementary and supplementary services and products through the initial connect created with the farmers. It plans to take a regional approach by saturating a region through provision of multiple products and services to all farmers in a region. With its hard work and passion to serve the farmers, we fully expect Aggois will live up to their expectations.

This blog post is part of a series that covers promising FinTechs that are making a difference to underserved communities. These start-ups receive support from the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program. The Lab is a part of CIIE.CO’s Bharat Inclusion Initiative and is co-powered by MSC. #TechForAll, #BuildingForBharat

Whrrl: A blockchain based disruptive financing model for agricultural practices

This blog is about a startup under the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program, which is supported by some of the largest philanthropic organizations across the world – Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, J.P. Morgan, Michael & Susan Dell Foundation, MetLife Foundation, and Omidyar Network.

Agricultural credit: A myth or reality?

According to a WHO report, India ranks 21 among the countries with the highest number of suicides per annum. A still bigger shocker is that the country has one of the highest rates of farmer suicides: 7.4% of the total suicides in the country (according to National Crime Records Bureau report). These farmer suicides are largely attributed to indebtedness and distress sales.

India has a fragmented agricultural system and is largely unorganized and unstructured, due to the presence of multiple levels of intermediaries spread across the agriculture value chain. Among 145 million Indian farmer households, 87% are small and marginal farmers (SHF), who own less than 2 hectares of land. With limited landholding and meagre sources of income from the farm, SHFs struggle even for sustenance. Agricultural reforms such as priority sector lending and farm loan waivers do not help much as access to institutional credit is still a distant dream for many SHFs. Most formal financial institutions are reluctant to offer credit to SHFs due lack of collaterals, absence of a formal credit history, and the inherently risky nature of agriculture. Turned away from formal sources, or wary of long turnaround times to process loans, SHFs usually turn to moneylenders for instant loans. These lenders charge exorbitant interest rates, which sometimes go as high as 75% to 350% per month. Burdened with past debt, farmers are compelled sell their produce to local traders at a loss to get cash quickly. The cycle of debt starts again as they take another loan to prepare for the next season. With shrinking profits, negligible or no savings, and the burden of yet another loan, these farmers remain trapped in a cycle of poverty, which leads to tragic endings like suicide.

But warehouse receipt financing (WRF), which offers small and marginal farmers a way to avail credit at cheaper rates from formal financial institutions, could be a game-changer and a life-saver.

What is warehouse receipt financing?

Warehouse receipt financing has been around in India since the 1960s. The Government of India enacted the Warehousing Development and Regulation Act (WDRA) in 2007 to develop and regulate warehouses and introduce a negotiable warehouse receipt system.

When commodity prices take a temporary dip due to a bumper harvest, small and marginal farmers can store their produce in warehouses while they wait for the prices to rise again. The warehouse provides farmers with a receipt once they deposit the produce. Farmer can then use these receipts, which contain details like the quantity and value of produce as per the current market rate, as collateral to negotiate short-term credit from financial institutions. Post-harvest credit can help farmers avoid distress sales, pay off previous loans, buy farm inputs for the next crop, and meet other expenses.

Whrrl’s eureka moment

Ashish, the co-founder of Whrrl, started his career as a chartered accountant and later moved onto debt syndication and financial advice to MSMEs. Ashish started to explore blockchain technology in 2018 in a bid to build an end-to-end solution for MSMEs. He co-founded the Blockchain Advisory Council (BAC) – an advisory and consulting firm specialized in blockchain and information technologies to explore the use-cases of blockchain in different industries across India.

Ashish developed an interest in WRF after reading about the Qingdao scandal, which involved the fraudulent use of warehouse receipts to raise finance. He researched the Qingdao scam and discovered that the agricultural warehouse frauds in India, which are also driven by forged receipts, are very similar to it.

Angry and with a firm resolve to solve this problem, Ashish decided to leverage his knowledge on blockchain technology to overcome gaps in traditional agri-warehouse lending. He discussed this idea with Abhishek Bhattacharya—a blockchain developer and Paul Scott—a tech entrepreneur, both of whom Ashish had met during his stint with BAC. The three joined hands as they saw an opportunity to create a positive impact on the lives of millions of farmers. Later, Ashish also roped in his wife Falguni Pandit, a tech professional. And thus, Whrrl was born, turning this idea into reality.

The unique pitch: Renovating the old setup

Whrrl is a B2B2C Blockchain PaaS start-up that provides a technology solution for warehouse receipt financing (WRF). Whrrl helps farmers, traders, and farmer producer companies (FPCs) raise working capital to tide over lengthy crop cycles that range from 6 to 12 months.

Whrrl works on a disruptive model unique to the current scenario. It collects data from warehouses and feeds it to its blockchain system, which creates an immutable record of the collateral

Whrrl works on a disruptive model unique to the current scenario. It collects data from warehouses and feeds it to its blockchain system, which creates an immutable record of the collateral

This helps lenders take better decisions by cutting out intermediaries. It also helps mitigate fraud due to the inherent features of blockchain—immutability, transparency, and real-time availability of the latest relevant data values on the network. These features enable financial institutions to estimate the value of the collateral (agriculture produce) accurately and, in turn, lend to SHFs and FPCs at reasonable and affordable rates.

Whrrl differentiates itself from traditional warehouse receipt (WHR) instruments in the following ways:

- The platform enables easy access to information and communication between warehouses and banks through automatic updates on the common platform. The modular infrastructure ensures that the data is recorded, stored, and updated in a distributed manner. This means that banks and warehouses no longer need to rely on centralized nodes for information.

- The “smart contract” system helps coordinate and enforce agreements between digitally networked participants without the need for traditional legal contracts. This helps digitize the records with minimal manual intervention.

- The platform also allows depositors to make commodity transactions through tradeable tokens. In case of default, banks could also use these token to sell the depositor’s produce and recover the loan amount.

Whrrl started its journey as a B2B platform. The founding team soon realized the need to move beyond the B2B space to create a direct impact on the farming community and make the lending process transparent and quick. To help borrowers overcome the tedious and time-consuming process involved in the disbursement of agri credit, the team developed a mobile application in late 2019.

Achievements and the impact made so far

In its journey so far, Whrrl has:

- Connected with more than 1,400 warehouses across India with five financing and government agencies as its customers and partners.

- Processed electronic warehouse receipts (e-WHRs) worth more than INR 3,500 crores (USD 468 million). Even during the COVID-19 pandemic, it facilitated INR 50 million (USD 0.67 million) worth of WHR loans.

- Won the PICUP Fintech award organized by the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry (FICCI) and the Indian Banks Association (IBA).

Roadblocks

Though Whrrl believes in inclusiveness and does not want to skew its lending toward large farmers, SHF lending is easier said than done. The start-up faced the following two major roadblocks in its journey:

- As most of Whrrl’s founding members started their careers in technical fields, they found it challenging to understand the credit requirements of their target segment—FPOs, farmers, and traders.

- Scalability was also a major challenge for Whrrl. The team lacked the acumen to help small and marginal farmers understand and appreciate the convenience of WRF. Most SHFs believe that WRF is solely for large farmers, which limits its adoption among their small and marginal counterparts.

FI Lab’s support to Whrrl

Despite the lockdown and other travel restrictions due to the pandemic, MSC conducted an on-field research study for Whrrl in their suggested areas of Jharkhand and Maharashtra. The objective was to assess the viability of its WRF product as a credit instrument for small and medium farmers, traders, and FPOs.

The study assessed the role of various players in the WRF value chain, such as farmers, FPOs, warehouse managers, and traders across Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh (UP), and Maharashtra. This helped Whrrl to understand the credit needs of its target segment better and to build a marketing and communication (MarCom) plan to enhance farmer outreach and make SHFs aware of the convenience WRF offers. The MarCom plan captured the nuances of pitching WRF product and communicating with the farmers.

Based on insights gained through the Lab, Whrrl started to develop a phygital (physical and digital) marketing and implementation strategy. They are using MarCom plan to enhance the productivity of their sales team through trainings and aligning the outreach activities across various channels.

The road ahead

Whrrl seeks to solve the working capital woes of the farming community and help farmers increase their income by 25-40%. The team is also ready to make its foray into other parts of the world, particularly in Southeast Asia and Africa. As its first step into the international market, Whrrl will soon start to work with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) Impact Accelerator to drive financial inclusion in Bangladesh. The start-up wants to build world-class credit products for the farming community. It aspires to become the solution of choice for asset-backed lending by making credit accessible and affordable, especially for SHFs.

This blog post is part of a series that covers promising FinTechs that make a difference to underserved communities. These start-ups receive support from the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program. The Lab is a part of CIIE.CO’s Bharat Inclusion Initiative and is co-powered by MSC. #TechForAll, #BuildingForBharat

Social assistance and information in the initial phase of the pandemic: Lessons from a household survey in India

India’s early response to the COVID-19 pandemic included several measures, including a nationwide lockdown, a sustained information campaign, and PMGKY—a major social protection package. This paper reports on the implementation of PMGKY based on a household survey. At its outset, PMGKY built on previous pro-people digital investments, including several established programs and direct benefit transfer to financial accounts. PMGKY successfully delivered benefits, including food rations, to millions of households.

Meanwhile, people did not always realize that they had received payments into their accounts despite the information campaign. At the same time, many found it challenging to reach cash-out points because of the disruptions related to the pandemic. These factors constrained the immediate realization of benefits. Performance was broadly uniform across different groups of recipients, with few significant systematic differences in the receipt of benefits reported by gender, urban/rural location, and category of ration card. The study also highlights the critical need to increase the spread of smartphones across the population.

The Center for Global Development first published this paper on 22nd July, 2021.

Bangladesh – the basket case that taught microfinance to the world

The world has a lot to thank Bangladesh for! Oral Rehydration Therapy, a simple combination of salt and sugar, has saved more than 70 million lives in the 45 years since ICDDR,B in Bangladesh first developed it. The Lancet called ORS “the most important medical advance of the 20th century”.

Bangladesh is also credited with the invention of joint liability group-based lending – the foundation for microcredit across the globe. 50 years into the independence of Bangladesh, we take a look at the contributions of its four most influential microfinance institutions:

- Grameen Bank originated a structured and formal approach to microfinance. As a result, it influenced generations of microfinance institutions (MFIs) at home, and built capacity abroad through Grameen Trust.

- BRAC developed a multiservice model of social development and enterprises in Bangladesh. It exported its expertise in microfinance across numerous geographies in Africa and Asia.

- ASA innovated a model for sustainable scaling up of a microfinance network through standardized self-reliant branches.

- BURO Bangladesh unlocked a holistic approach toward microfinance by integrating open savings mechanisms, pivoting away from the industry’s exclusive emphasis on lending.

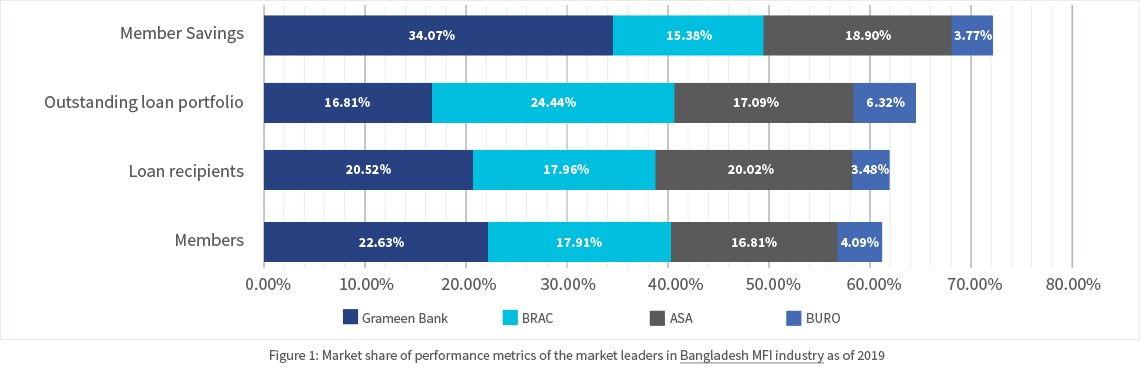

These four entities collectively have >60% of the market share among the 495 MFIs that Credit & Development Forum (CDF) reports on.

1. Grameen Bank: the origin of microfinance

The genesis of formalized microfinance in Bangladesh began during the Bangladesh famine of 1974. Muhammad Yunus, then a professor at the University of Chittagong visited Jobra. There, he learned that the basket weavers relied on exploitative money lenders to buy their raw materials. Yunus decided to make a small loan of USD 27 (equivalent to BDT 856 at the time) out of his pocket to a group of 42 families so they can produce items and sell them for profit. Seeing the positive impact this had, Yunus developed the guidelines for Grameen Bank. The Grameen Bank project started in Jobra in 1976 and was extended in 1979 to Tangail district with support from the Bangladesh Bank. In 1983, the Grameen Bank project was established as an independent bank under the Grameen Bank Ordinance 1983.

The Grameen approach broke barriers of availing credit for the poor by pioneering the joint-liability lending model, offering collateral-free loans. Grameen mainly served women as it found that they generally repay loans on time, invest their money for productive purposes, and make expenditures to improve the quality of life of family members. Grameen also believed that this increased women’s agency over resources by enhancing their traditional role as household budget managers.

After the 1998 floods, Grameen Bank faced high levels of delinquency and reinvented itself as “Grameen II”, which offered both savings services and (nominally at least) more flexible repayment options. Within three years, Grameen’s deposit base tripled and its loans outstanding doubled.

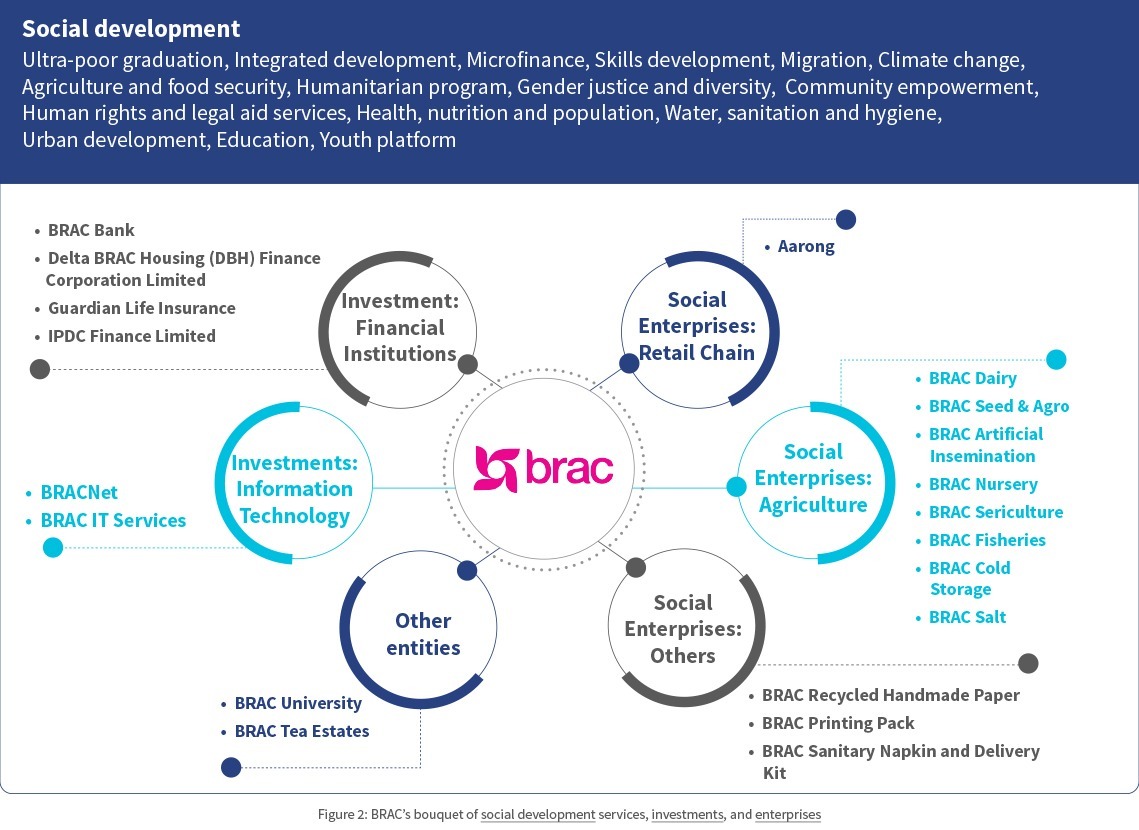

2. BRAC: a multi-faceted approach to social development

Sir Fazle Hasan Abed initiated BRAC as a project in 1972 at Sulla, a sub-district of Sunamganj, in Bangladesh. This small-scale relief and rehabilitation project helped returning refugees after the Liberation War by building homes and fishing boats. In the late 1970s, BRAC focused on combating diarrhea, through the Oral Therapy Extension Program (OTEP). It trained mothers to prepare and administer oral rehydration solution (ORS) from molasses and salt – ingredients available in every Bangladeshi home.

In 1986, BRAC started its Rural Development Program (RDP) consisting of four pillars:

- Institution building

- Functional education and training

- Microcredit

- Income and employment generation

From there, BRAC rapidly evolved into the world’s largest, most feted and diverse not for profit organization, offering holist development solutions to millions of poor people across the globe. Microcredit was but one strand of BRAC’s multi-faceted interventions to address poverty.

3. ASA: a frugal alternative for sustainable microfinance

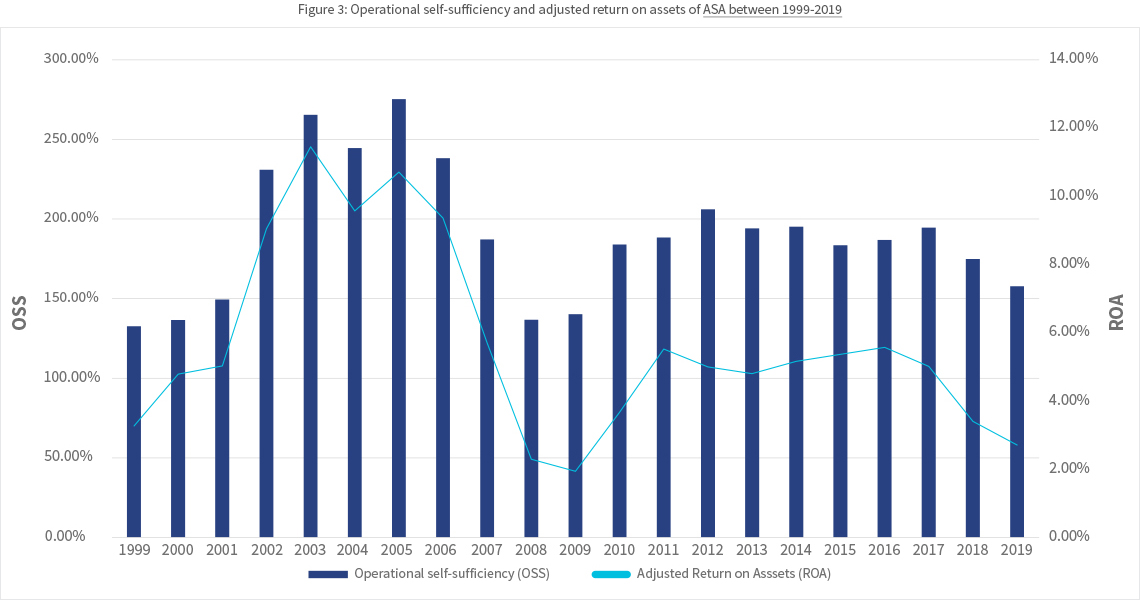

Md. Shafiqul Haque Choudhury established ASA in 1978 to empower rural landless villagers from the bottom up through people’s organizations. Initially, ASA attempted to combine social development with credit provision, similar to BRAC’s approach. However, in 1991, ASA pivoted to a sole focus on microcredit lending. The objective of this shift was to overcome a dependence on international donor agencies and become a specialized microfinance organization that was financially self-sufficient. ASA soon became the most profitable MFI in Bangladesh, generating annual net surpluses since 1992. As a result, ASA consistently recorded some of the highest return on assets and operational self-sufficiency among MFIs. As of 2019, ASA has a return on assets of 5.9% and a return on equity of 11.11%.

ASA’s self-reliant model is based on standardization of operations and streamlining of services. An easily replicable and low-cost branch model, and decentralized approach allowed ASA to make quick decisions. ASA was able to reinvest surpluses from the individual branch operations to multiply their branches, turning the organization into a fully self-sufficient entity independent of donors and commercial creditors alike. ASA focused on growing its standard product instead of product diversification, which resulted in ASA capturing a large share of the untapped market through its efficient delivery mechanism.

4. BURO Bangladesh: bridging the gap between microcredit and microfinance

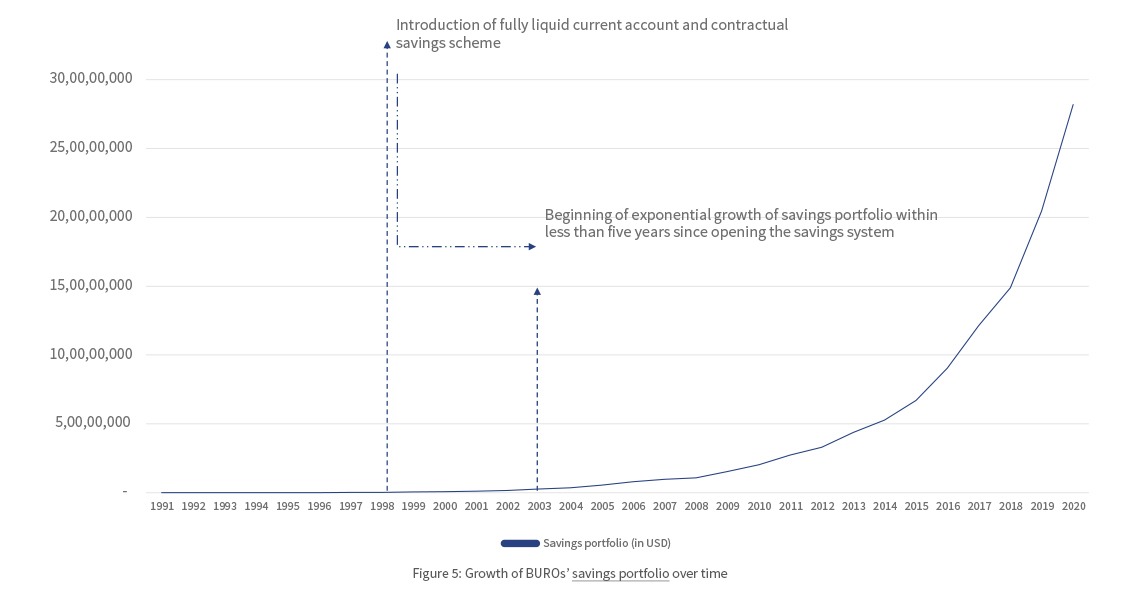

Since its inception in 1990, BURO identified and responded to poor people’s need for savings services. Grameen Bank and BRAC offered only locked-in “compulsory” savings. This meant that customers could not withdraw their savings at will, and were only able to access them when permanently leaving the organization. BURO introduced partial savings withdrawal in 1990, and moved to completely open access saving system unaffected by loan outstanding in 1998. This led to a substantial increase in deposits and net savings. BURO’s approach led to protests and mass default by Grameen Bank’s clients in the mid 1990s, demanding access to their locked-in savings.

Based on the experience gained during its formative years, BURO acknowledged that microcredit in a vacuum is not effective in significant poverty alleviation, let alone poverty eradication. BURO revolutionized the microcredit landscape of Bangladesh by overcoming the industry’s obsession with credit alone and integrating savings into the range of offerings for the clients. BURO continues to lead much of the innovation and broadening of the range of financial services offered by MFIs in the country.

5. How did these four perform?

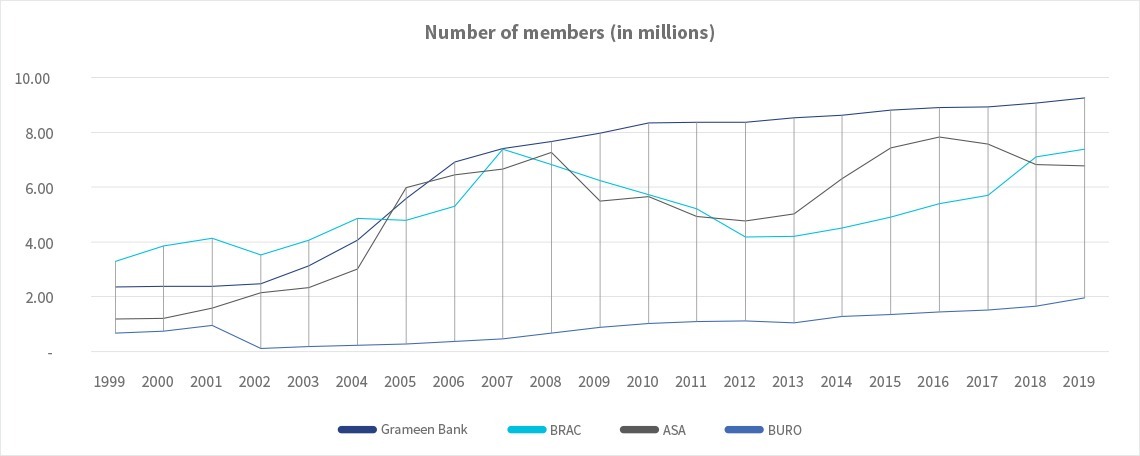

The graph below highlights the ebb and flow of membership amongst the “big four” as they grew and adjusted overtime. Grameen Bank’s rapid growth in membership starting in 2002 reflects the introduction of the popular Grameen II model. The reduction in membership by BRAC and ASA from 2007 highlights their concerns about multiple membership and over indebtedness, which was beautifully highlighted by Chen and Rutherford in 2013. There is little question that multiple membership of MFIs continues today – indeed it offers a way for borrowers to navigate the largely inflexible annual loan with weekly repayments offered by them all.

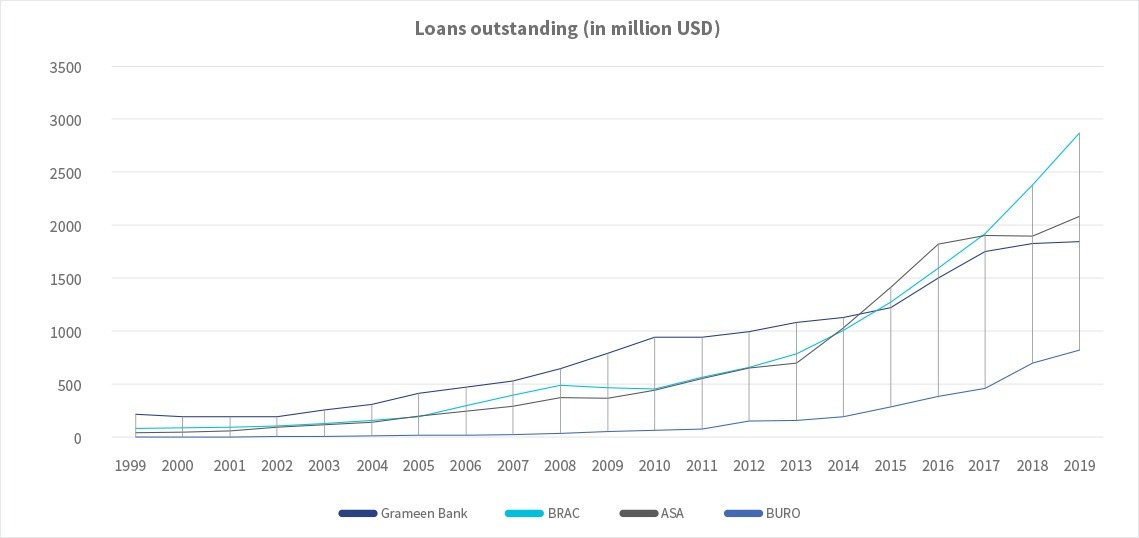

Loans outstanding have grown similarly, but the scope and scale of BRAC and ASA’s larger individual lending programs means that their average loan size per member is significantly higher than that of Grameen Bank.

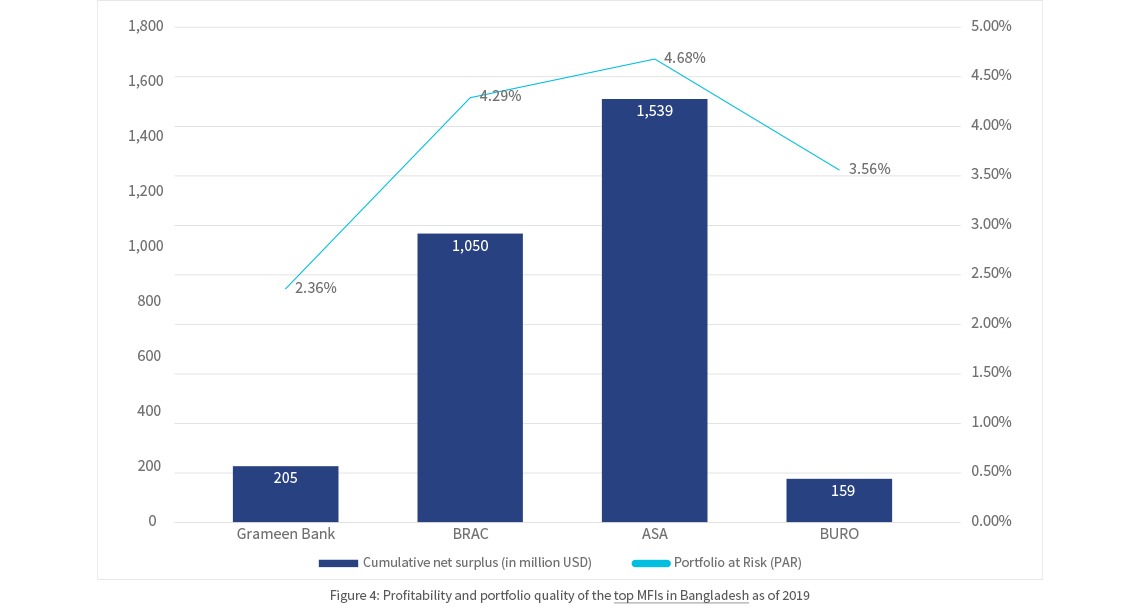

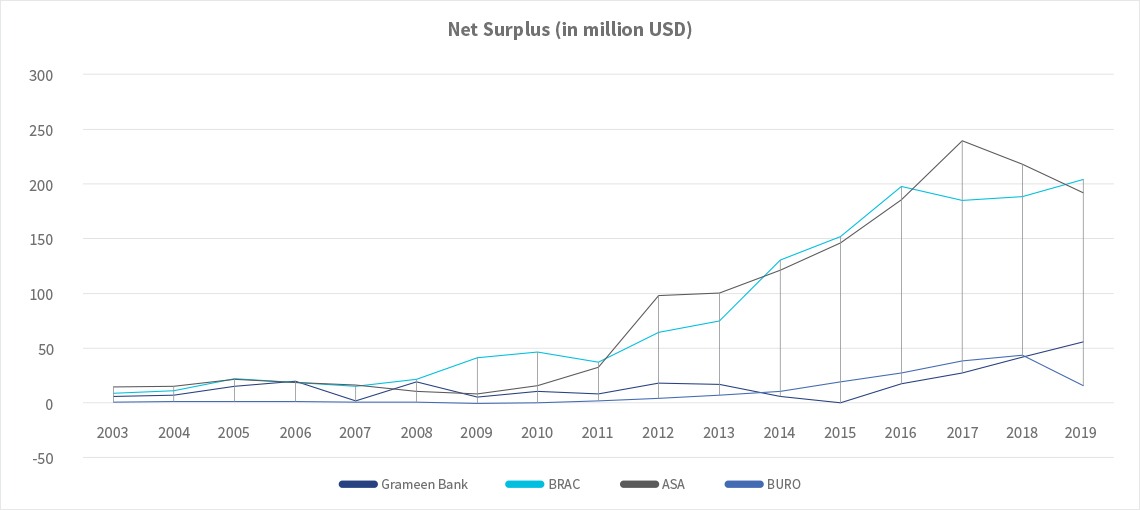

The profitability of these organizations also varies significantly. ASA, through is simplified model, and BRAC through cross subsidies from its other programs, generating much larger surpluses each year.

6. Influence and global expansion of microfinance models of Bangladesh

The biggest impact that came as a result of Grameen Bank’s early success was convincing the banks and other people that the poor are bankable, they utilize their loan and repay on time, performing better in contrast to the wealthy borrowers of the bank. The simple effectiveness of the model conceived by Grameen Bank has inspired many NGOs to emulate the model and offer similar financial services to the poor. Professor Yunus created Grameen Trust in 1989 as a private, not-for-profit NGO to cater to the demands of people and organizations that wanted to learn how to replicate the success of Grameen Bank. Since its inception, Grameen Trust has provided assistance to 151 organizations in 41 countries.

BRAC rapidly expanded its operations across geographies in Africa and Asia in the 21st century. BRAC established Stichting BRAC International in 2009 as a non-profit foundation headquartered in the Netherlands to manage all BRAC entities outside Bangladesh. BRAC commenced operations in Afghanistan, Sri Lanka, Uganda, Tanzania, Pakistan, South Sudan, Sierra Leone, Liberia, the Philippines, Myanmar, Nepal, and Rwanda in a span of less than two decades from 2002 to 2018. By 2020, BRAC had already been ranked the #1 NGO in the world for the fifth consecutive time by NGO Advisor, an independent Geneva-based media organization. BRAC ranked as the top NGO for the first time in the Global Journal’s list of the 100 Best NGOs in the world in 2013.

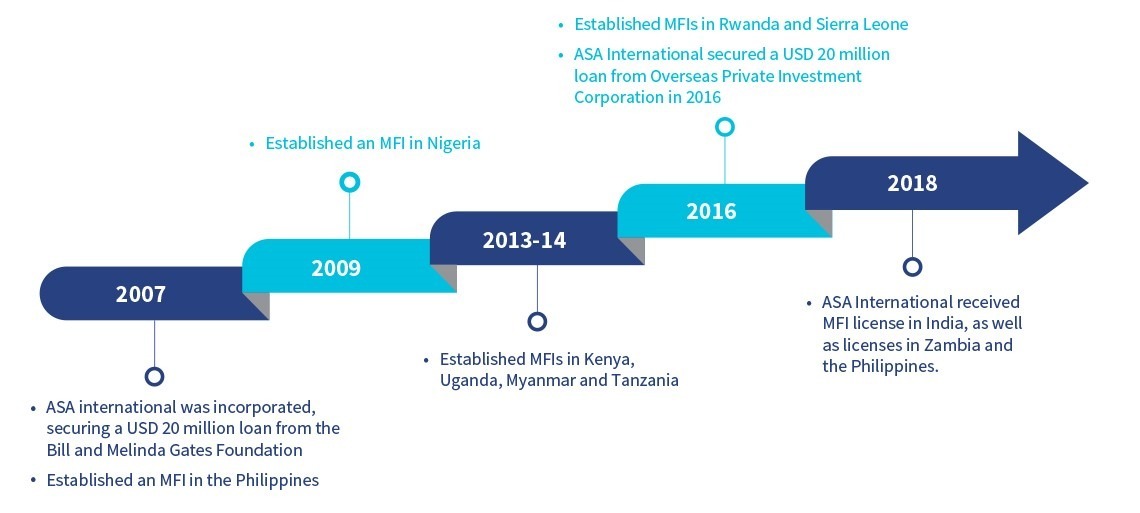

ASA has also expanded its operations beyond Bangladesh, as international roll-out of the ASA model has resulted in sustainable growth and returns.

ASA International currently has 1,961 branches, over 2.4 million clients, and an outstanding loan portfolio of USD 418.5 million in thirteen countries outside Bangladesh.

Fifty years on Bangladesh has exported a remarkable diversity of products from garments to ORS, but one of its key legacies is microfinance – in many forms.