This blog is about a startup under the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program, which is supported by some of the largest philanthropic organizations across the world – Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, J.P. Morgan, Michael and Susan Dell Foundation, MetLife Foundation, and Omidyar Network.

Startups are rarely known to follow conventional wisdom. They believe in turning any traditional business model on its head. Shantanu Singh and Eral Ravi also did something similar when they decided to transform their childhood friendship into an entrepreneurial partnership. Both come with 18+ years of consulting and practice experience human resources and have a strong understanding of the market forces in this domain. The third co-founder, Aashutosh Chaudhary joined them as a developer when they were building their first startup, Unnati Online—a recruitment technology company—and ultimately rose to become a co-founder and CTO at Flexi Salary.

When it all began

The genesis of Flexi Salary is rooted in Unnati Online. Shantanu and Ravi launched 30 “Rozgar Kendras” during their stint at Unnati – a tech-enabled employment exchange for hiring informal sector and entry-level workers – in Gurgaon. Nearly 20,000 blue-collar workers registered at these Rozgar Kendras within two to three months. This stint gave the founders a chance to observe a large number of workers closely and interact with them. They noticed that nearly all workers were visibly strapped for cash and relied extensively on social borrowing, especially after the 15th of the month.

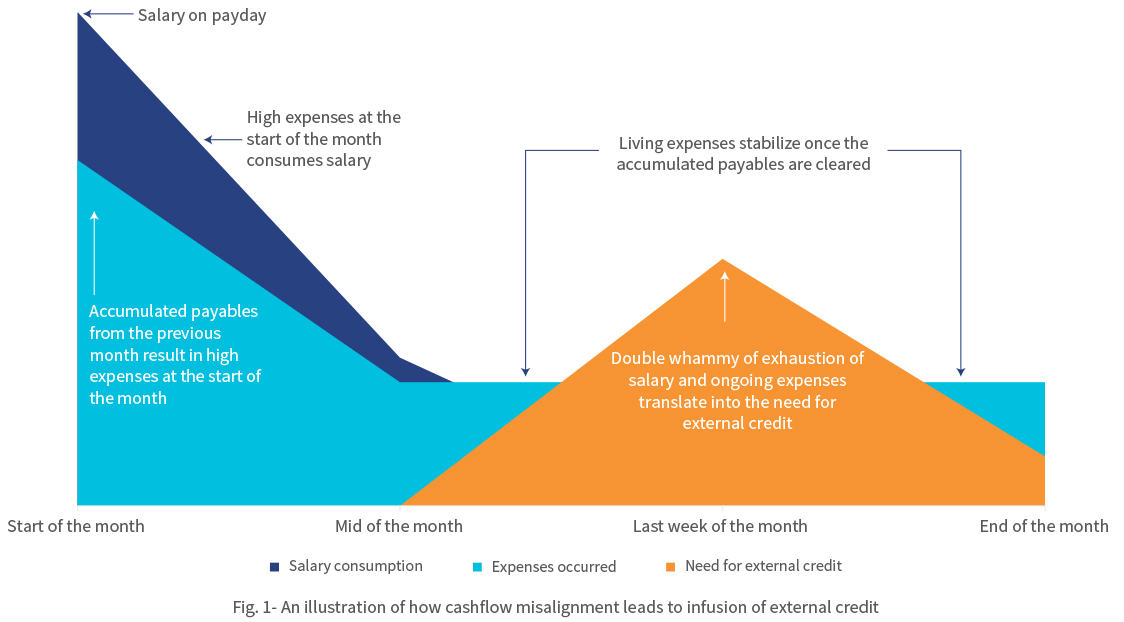

Although “living paycheck-to-paycheck” and “waiting for salary day” have become an accepted way of life for millions of Indians, the founders recognized that these are symptoms of a deep-routed misalignment in cash flow. They believed that FinTechs that provide credit access acted as temporary pain-relievers, as they merely addressed a symptom (an immediate cash crunch) rather than solving the underlying problem (cashflow misalignment). The following graphic illustrates how cash misalignment comes into being.

The figure above represents the cash-flow pattern of a salaried employee from the low- and middle-income (LMI) segment across a month. Expenses peak at the beginning of the month due to recurrent liabilities, such as outstanding bills, rent charges, and so on. Often these overdue bills are pushed to the next payday, which can be any of the first seven days of the next month. Once the employee clears the post-dated bills at the beginning of the month, the expenses decrease but not significantly since the living expenses remain consistent. The steady decline in funds as the month progresses creates a need for external credit. The cycle repeats when the next payday arrives and the bills for the previous month are overdue. This leads to a dreadful phenomenon of living paycheck to paycheck.

Flexi Salary understood that the “monthly salary” system, that is, the mindset of “wait till month end to get paid” generates a cash flow mismatch that causes financial distress for LMI households in India every month. The disruptive question was in front of them—“When expenses are daily, why not income?”

The founders envisioned a new salary system to solve this problem, which would give workers instant access to the money as and when they earned it. The founders understood that this mismatch was an overwhelming problem faced by millions of Indians and therefore was an opportunity to build a company to cater to this large market demand. And so, Flexi Salary was born.

No more monthly salaries

Flexi Salary is a new “instant salary” system in which employees are paid immediately for every workday. Every workday, the day’s salary is loaded into each employee’s salary wallet. As employees work through the month, their earned salary accumulates in their salary wallet. Instead of waiting until the month’s end, employees can withdraw their earnings from their wallets any time they need money. This is done by real-time on-tap liquidity provided by Flexi Salary and their partner NBFCs, which offers timely access to salary for employees. The employees can thereafter repay the withdrawn amount when they get paid the full salary by their employers at the end of the month.

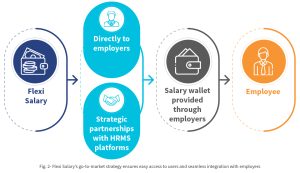

Unlike other FinTechs in this space, Flexi Salary not a loan app. It is not an app that users can use to take credit in a piecemeal manner to meet their liquidity needs. Instead, it provides the customers with continuous access to funds that they have already earned. Flexi Salary stays true to its mission by offering its product to employees through their employers alone. The startup partners with companies that enable the Flexi Salary system for their employees. Once an employer introduces the wallet in the workplace and the employees choose this option, they do not have to wait for the payday or seek additional approval from their employer to withdraw their daily salaries—Flexi Salary’s app handles these aspects.

Flexi Salary has partnered with lenders that provide liquidity flexibly to the users at any time of the month. When the user receives their wages at the end of the month, they can repay the availed amount to Flexi Salary. Neither the employer nor the payroll teams need to get involved. The payroll team and their usual operations can continue as per the established monthly cycle, while Flexi Salary’s wallet powers each employee with the convenience of flexible salary.

Besides being a workplace perk, the facility to avail salary flexibly ensures that the employees are well-funded, which minimizes the chances of having to look elsewhere to make ends meet, thereby falling into a potential debt trap. Flexi Salary has also partnered with leading human resource management system (HRMS) players in the industry, including Quess Corp, Adetto HR, and Hono HR. Powered by such partnerships, a company that uses any of these HRMS solutions can implement Flexi Salary easily within their workplace in a plug-and-play mode.

Battles to win:

The founders believe in validating the product—and what better way to do this than by engaging HR leaders and other decision-makers in trials before rolling it out to the employees. While Flexi Salary has had significant early traction in its journey, generating trials for such leaders has been an uphill task. Moreover, the uncertainty in the business environment posed by COVID-19 has prolonged some of the business discussions indefinitely.

Adhering to the same spirit with which they set out to solve the problem of cash flow misalignment, Flexi Salary took these roadblocks head-on with grit and commitment. The team has used the personal networks of founders and connections from investors. One of the advantages of Flexi Salary has been Shantanu’s alumni network at Xavier Labor Relations Institute- XLRI, which has one of the best human resources MBA programs in the country. The team has accessed the alumni network to tap into HR leadership in various firms in India. Not letting the crisis go to waste, Flexi Salary has been focusing on improving its product through continuous product development and pilots. These refinements will ensure that the product is scalable. As soon as the second wave recedes, the team can hit the ground running to realize their dream of enabling flexible salaries for everyone in India.

Support from the FI Lab

Through CIIE.CO and MSC, the Lab has been helping their business in two phases, besides making the right connections.

In the first phase, the Lab helped Flexi Salary to identify the appropriate product positioning of its app, based on ground-level research with white-collar as well as blue and grey collar employees to identify their problems and needs. Using a human-centered design framework on the salary wallet model and expense allowance model, MSC helped Flexi Salary to strike a balance with blue-collar as well as entry-level white-collar workers.

In the ongoing second phase of the TA, the Lab has been helping Flexi Salary in its scale-up by identifying companies that can act as aggregation points through strategic partnerships. Identification of such strategic partnerships can unlock access to many employers and thus, employees. We have also supported Flexi Salary in developing its business development strategy and implementation of the same to ensure that the team can scale up faster.

Collectively, the advisory support of the Lab will ensure that Flexi Salary finds the right product-market fit at an early stage in its journey. Once this is achieved, Flexi Salary would scale up efficiently through bootstrapping and minimal external funding.

Way forward:

The founders want to establish the concept of flexible salaries across industries. In the short term, the founders hope to popularize Flexi Salary as the “employee-friendly” way of paying salaries to employees. They hope to partner with companies in a diverse range of industries to enable Flexi Salary for their employees making the product industry-agnostic. Over the next five years, they hope to replace the concept of “monthly salary” with flexible salary and establish it as the preferred salary payment system across India Inc.

This blog post is part of a series that covers promising FinTechs that are making a difference to underserved communities. These start-ups receive support from the Financial Inclusion Lab accelerator program. The Lab is a part of CIIE.CO’s Bharat Inclusion Initiative and is co-powered by MSC. #TechForAll, #BuildingForBharat

Two of the founders, Anshul and Krishna, met at an organization that works with a large number of blue-collar employees. Here, they saw that blue-collar workers struggled with exclusion from formal financial services. These workers frequently needed loans and salary advances. They lacked knowledge about Employee State Insurance (ESIC), provident fund (PF), and other statutory deductions as well as workplace benefits. Moreover, the workers spent close to a tenth of their income each month on unnecessary expenses like bank withdrawal charges and late payment fees.

Two of the founders, Anshul and Krishna, met at an organization that works with a large number of blue-collar employees. Here, they saw that blue-collar workers struggled with exclusion from formal financial services. These workers frequently needed loans and salary advances. They lacked knowledge about Employee State Insurance (ESIC), provident fund (PF), and other statutory deductions as well as workplace benefits. Moreover, the workers spent close to a tenth of their income each month on unnecessary expenses like bank withdrawal charges and late payment fees.